The document discusses various topics related to solar energy generation including:

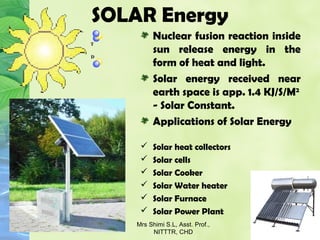

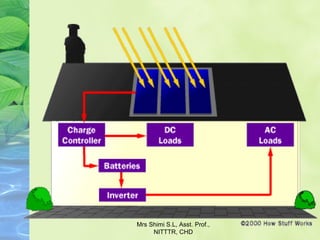

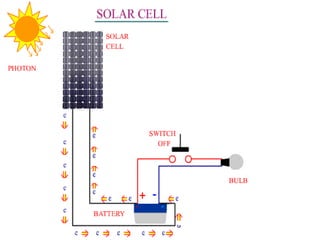

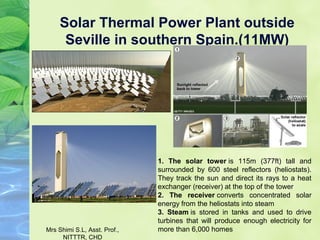

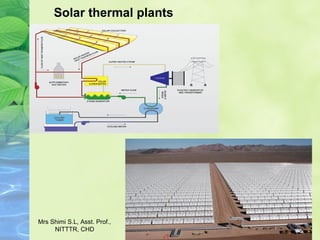

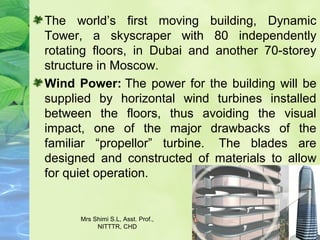

- Solar energy is generated through nuclear fusion reactions inside the sun and can be harnessed using technologies like solar cells, solar heat collectors, and solar power plants.

- Applications of solar energy include generating electricity at utility-scale solar power plants as well as powering vehicles, heating homes and water, and providing power in remote locations.

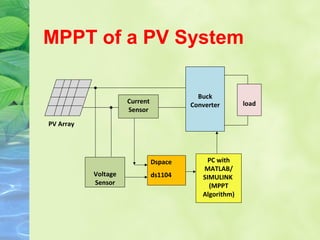

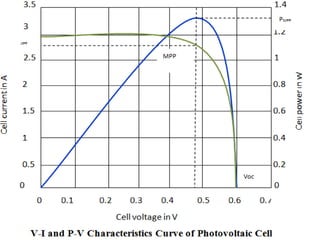

- Maximizing the power extracted from solar panels requires techniques like automatic sun tracking and searching for maximum power point conditions.

- Emerging solar technologies include solar farms in space that beam microwave energy to receivers on Earth and solar panels integrated into buildings.

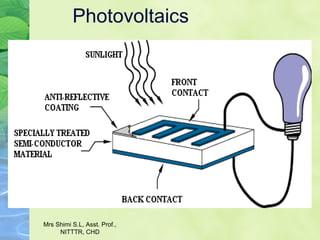

![The photovoltaic effect is the creation of voltage or electric current in

a material upon exposure to light. Though the photovoltaic effect is

directly related to the photoelectric effect, they are different processes.

In the photoelectric effect, electrons are ejected from a material's

surface upon exposure to radiation. The photovoltaic effect differs in

that electrons are transferred between different bands (i.e., from the

valence to conduction bands) within the material, resulting in the

buildup of voltage between two electrodes.[1]

In most photovoltaic applications the radiation is sunlight, which is why

the devices are known as solar cells. In the case of a p-n junction

solar cell, illuminating the material creates an electric current as

excited electrons and the remaining holes are swept in different

directions by the built-in electric field of the depletion region.[2]

The photovoltaic effect was first observed by

Alexandre-Edmond Becquerel in 1839.[3][4]

Mrs Shimi S.L, Asst. Prof.,

NITTTR, CHD](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/solarenergyapplicationforelectricpowergeneration-150423005223-conversion-gate01/85/Solar-energy-application-for-electric-power-generation-36-320.jpg)

![An unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV), commonly known as

a drone, is an aircraft without a human pilot on board. Its flight

is either controlled autonomously by computers in the vehicle,

or under the remote control of a navigator, or pilot (in military

UAVs called a Combat Systems Officer on UCAVs) on the

ground or in another vehicle.

There are a wide variety of drone shapes, sizes, configurations,

and characteristics. Historically, UAVs were simple remotely

pilotedaircraft, but autonomous control is increasingly being

employed.[1]

Their largest use is within military applications. UAVs are also

used in a small but growing number of civil applications, such

as firefightingor nonmilitary security work, such as surveillance

of pipelines. UAVs are often preferred for missions that are too

"dull, dirty, or dangerous" for manned aircraft.Mrs Shimi S.L, Asst. Prof.,

NITTTR, CHD](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/solarenergyapplicationforelectricpowergeneration-150423005223-conversion-gate01/85/Solar-energy-application-for-electric-power-generation-41-320.jpg)

!["Geothermal Engineering" redirects here. For the British company specializing in the development of geothermal resources, see

Geothermal Engineering Ltd..

Steam rising from the Nesjavellir Geothermal Power Station in Iceland.

Geothermal energy is thermal energy generated and stored in the Earth. Thermal energy is the energy that determines the

temperature of matter. The geothermal energy of the Earth's crust originates from the original formation of the planet (20%) and

from radioactive decay of minerals (80%).[1][2]

The geothermal gradient, which is the difference in temperature between the core of

the planet and its surface, drives a continuous conduction of thermal energy in the form of heat from the core to the surface. The

adjective geothermal originates from the Greek roots γη (ge), meaning earth, and θερμος (thermos), meaning hot.

At the core of the Earth, thermal energy is created by radioactive decay[1]

and temperatures may reach over 5000 °C (9,000 °F).

Heat conducts from the core to surrounding cooler rock. The high temperature and pressure cause some rock to melt, creating

magma convection upward since it is lighter than the solid rock. The magma heats rock and water in the crust, sometimes up to

370 °C (700 °F).[3]

From hot springs, geothermal energy has been used for bathing since Paleolithic times and for space heating since ancient

Roman times, but it is now better known for electricity generation. Worldwide, about 10,715 megawatts (MW) of geothermal

power is online in 24 countries. An additional 28 gigawatts of direct geothermal heating capacity is installed for district heating,

space heating, spas, industrial processes, desalination and agricultural applications.[4]

Mrs Shimi S.L, Asst. Prof.,

NITTTR, CHD](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/solarenergyapplicationforelectricpowergeneration-150423005223-conversion-gate01/85/Solar-energy-application-for-electric-power-generation-43-320.jpg)

![Applications of the Stirling engine range from mechanical propulsion to

heating and cooling to electrical generation systems. A Stirling engine is a

heat engine operating by cyclic compression and expansion of air or other gas,

the "working fluid", at different temperature levels such that there is a net

conversion of heat energy to mechanical work.[1][2]

The Stirling cycle heat engine

can also be driven in reverse, using a mechanical energy input to drive heat

transfer in a reversed direction (i.e. a heat pump, or refrigerator).

There are several design configurations for Stirling engines that can be built,

many of which require rotary or sliding seals, which can introduce difficult

tradeoffs between frictional losses and refrigerant leakage. A free-piston variant

of the Stirling engine can be built, which can be completely hermetically sealed,

reducing friction losses and completely eliminating refrigerant leakage. For

example, a Free Piston Stirling Cooler (FPSC) can convert an electrical energy

input into a practical heat pump effect, used for high-efficiency portable

refrigerators and freezers. Conversely, a free-piston electrical generator could

be built, converting a heat flow into mechanical energy, and then into electricity.

In both cases, energy is usually converted from/to electrical energy using

magnetic fields in a way that avoids compromising the hermetic seal.

Mrs Shimi S.L, Asst. Prof.,

NITTTR, CHD](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/solarenergyapplicationforelectricpowergeneration-150423005223-conversion-gate01/85/Solar-energy-application-for-electric-power-generation-45-320.jpg)

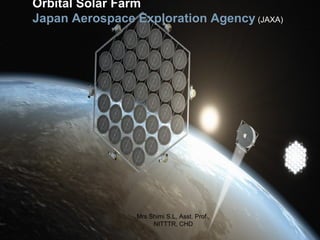

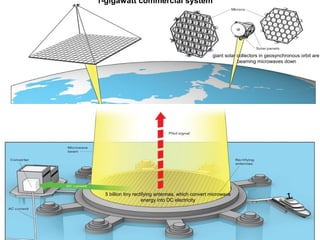

![Imagine looking out over Tokyo Bay from high above and seeing a man-made island in the harbor, 3 kilometers long. A

massive net is stretched over the island and studded with 5 billion tiny rectifying antennas, which convert microwave energy

into DC electricity. Also on the island is a substation that sends that electricity coursing through a submarine cable to Tokyo,

to help keep the factories of the Keihin industrial zone humming and the neon lights of Shibuya shining bright.

But you can’t even see the most interesting part. Several giant solar collectors in geosynchronous orbit are beaming

microwaves down to the island from 36 000 km above Earth.

It’s been the subject of many previous studies and the stuff of sci-fi for decades, but space-based solar power could at last

become a reality—and within 25 years, according to a proposal from researchers at the

Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA). The agency, which leads the world in research on space-based solar power

systems, now has a technology road map that suggests a series of ground and orbital demonstrations leading to the

development in the 2030s of a 1-gigawatt commercial system—about the same output as a typical nuclear power plant.

It’s an ambitious plan, to be sure. But a combination of technical and social factors is giving it currency, especially in Japan.

On the technical front, recent advances in wireless power transmission allow moving antennas to coordinate in order to

send a precise beam across vast distances. At the same time, heightened public concerns about the climatic effects of

greenhouse gases produced by the burning of fossil fuels are prompting a look at alternatives. Renewable energy

technologies to harvest the sun and the wind are constantly improving, but large-scale solar and wind farms occupy huge

swaths of land, and they provide only intermittent power. Space-based solar collectors in geosynchronous orbit, on the other

hand, could generate power nearly 24 hours a day. Japan has a particular interest in finding a practical clean energy source:

The accident at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant prompted an exhaustive and systematic search for alternatives,

yet Japan lacks both fossil fuel resources and empty land suitable for renewable power installations.

Soon after we humans invented silicon-based photovoltaic cells to convert sunlight directly into electricity, more than

60 years ago, we realized that space would be the best place to perform that conversion. The concept was first proposed

formally in 1968 by the American aerospace engineer Peter Glaser. In a seminal paper, he acknowledged the challenges of

constructing, launching, and operating these satellites but argued that improved photovoltaics and easier access to space

would soon make them achievable. In the 1970s, NASA and the U.S. Department of Energy carried out serious studies on

space-based solar power, and over the decades since, various types of solar power satellites (SPSs) have been proposed.

No such satellites have been orbited yet because of concerns regarding costs and technical feasibility. The relevant

technologies have made great strides in recent years, however. It’s time to take another look at space-based solar power.

A commercial SPS capable of producing 1 GW would be a magnificent structure weighing more than 10 000 metric tons

and measuring several kilometers across. To complete and operate an electricity system based on such satellites, we would

have to demonstrate mastery of six different disciplines: wireless power transmission, space transportation, construction of

large structures in orbit, satellite attitude and orbit control, power generation, and power management. Of those six

challenges, it’s the wireless power transmission that remains the most daunting. So that’s where JAXA has focused its

research.

Illustration: John MacNeillThe Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency is working on several models for solar-collecting

satellites, which would fly in geosynchronous orbit 36 000 kilometers above their receiving stations. With the basic model

[top left-hand side], the photovoltaic-topped panel’s efficiency would decrease as the world turned away from the sun. The

advanced model [top right-hand side] would feature two mirrors to reflect sunlight onto two photovoltaic panels. This model

would be more difficult to build, but it could generate electricity continuously.

In either model, the photovoltaic panels would generate DC current, which would be converted to microwaves aboard the

satellite. The satellite’s many microwave-transmitting antenna panels would receive a pilot signal from the ground, allowing

Mrs Shimi S.L, Asst. Prof.,

NITTTR, CHD](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/solarenergyapplicationforelectricpowergeneration-150423005223-conversion-gate01/85/Solar-energy-application-for-electric-power-generation-46-320.jpg)