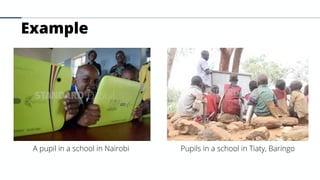

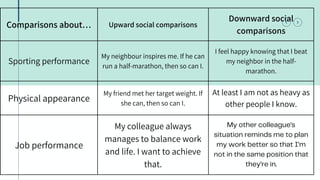

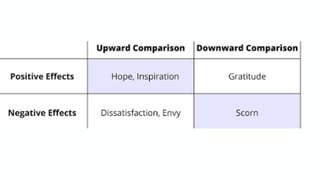

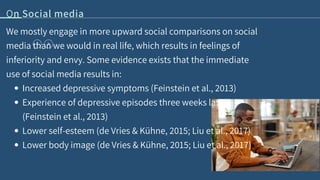

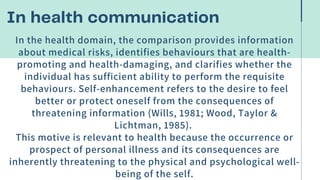

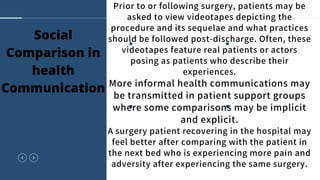

This document provides an overview of social comparison theory and its applications. It discusses Leon Festinger's 1954 theory that people have an innate drive to evaluate themselves against others. There are two types of social comparison: upward, where one compares to superior others to improve; and downward, where one compares to inferior others to feel better. Social comparison occurs in domains like health, where people gauge their abilities and risks. It can impact mental health and is common on social media. The document concludes by discussing uses of social comparison in health communication and providing references.