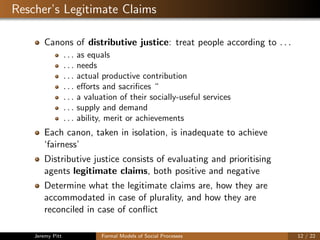

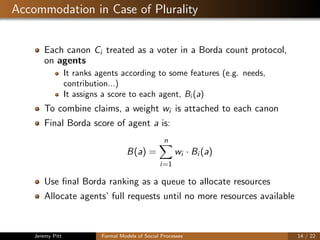

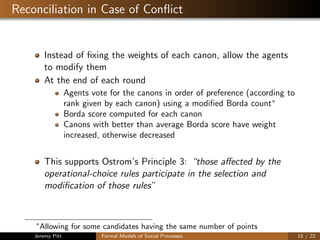

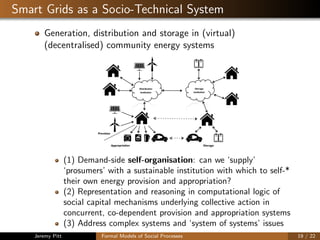

The document discusses formal models of social processes, focusing on computational justice for fair and sustainable resource allocation in socio-technical systems. It explores resource management principles inspired by Elinor Ostrom and distributive justice theories, highlighting the significance of self-governing institutions for efficient resource sharing. The findings emphasize the importance of fairness algorithms and self-governance mechanisms in addressing future energy challenges through community-oriented solutions.

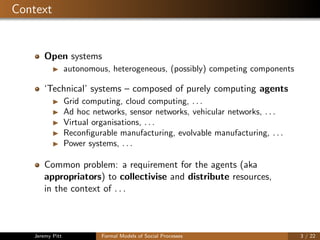

![Self-Governing the Commons with Institutions

Definition: “set of working rules that are used to determine

who is eligible to make decisions in some arena, what actions

are allowed or constrained, ... [and] contain prescriptions that

forbid, permit or require some action or outcome” [Ostrom]

Conventionally agreed, mutually understood, monitored and

enforced, mutable and nested

Nesting: tripartite analysis

operational-, collective- and constitutional-choice rules

Decision arenas [Action Situations]

Requires representation of Institutionalised Power

Jeremy Pitt Formal Models of Social Processes 7 / 22](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/smartseminarseries-presentation-jeremypitt-141217214406-conversion-gate01/85/SMART-Seminar-Series-Formal-Models-of-Social-Processes-7-320.jpg)

![Self-Organising Electronic Institutions (SOEI)

Electronic Institutions

Formalise structural, functional and procedural aspects of

institutions in mathematical or computational form

Self-Organising: selection and modification of structures,

functions, and procedures are determined by the members

inc

rep

1

1 1 2

3

4

4’

5

a b b a

a b b ∼ a

A DG

A = DG

A

DG

ADG

ADG

ADG

scr1

scr2

ocr1

scr4

scr5

wdMethod

raMethod

wdMethod

v(·)

v(·)

M 7! [0, P]

M 7! [0, P]

SC

v(·)

{SC [ OC}

chair

chair

chair

chair

chair

(a) Institution 1

scr1

scr2

ocr2

scr3

scr4

scr5

wdMethod

raMethod

W

wdMethod

v(·)

v(·)

M 7! [0, P]

M 7! [0, P]

v(·) W

SC

v(·)

{SC [ OC}

chair

chair

chair

chair

chair

chair

(b) Institution 2

Figure 1: Rules relationships: solid lines denote input and output of the rules; dashed lines denote chair assignment. (a) ...

(b) ...

scr3 scr2

scr1

ocr1

wdMethod DG1

raMethod

wdMethodDG3 DG2

{v(·)}a2DG3 {v(·)}a2DG2

{v(·)}a2DG1

{da(·)}a2A

{ra(·)}a2A

(a) Institution 1

scr3 scr2

scr1 scr4

ocr2

wdMethod DG1

WraMethod

DG1

wdMethodDG3 DG2

{v(·)}a2DG3

{v(·)}a2DG2

{v(·)}a2DG1 {v(·)}a2DG1

W

{da(·)}a2A

{ra(·)}a2A

(b) Institution 2

Figure 2: Rules relationships: solid lines denote input and output of the rules; dashed lines denote chair assignment. (a) ...

(b) ...

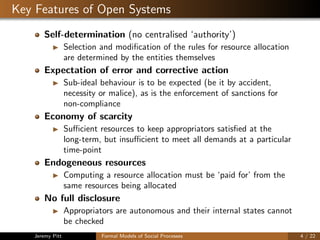

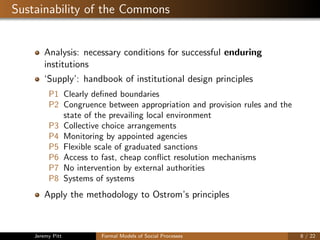

Self-Organising electronic institutions represented in

framework of dynamic norm-governed systems (Artikis, 2012)

SOEI encapsulating Ostrom’s institutional design principles can

be axiomatised in computational logic using the Event

Calculus, and directly executed

Experiments showed that the more principles that were

axiomatised, it was more likely that the institution could

maintain ‘high’ levels of membership and sustain the resource

Jeremy Pitt Formal Models of Social Processes 9 / 22](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/smartseminarseries-presentation-jeremypitt-141217214406-conversion-gate01/85/SMART-Seminar-Series-Formal-Models-of-Social-Processes-9-320.jpg)

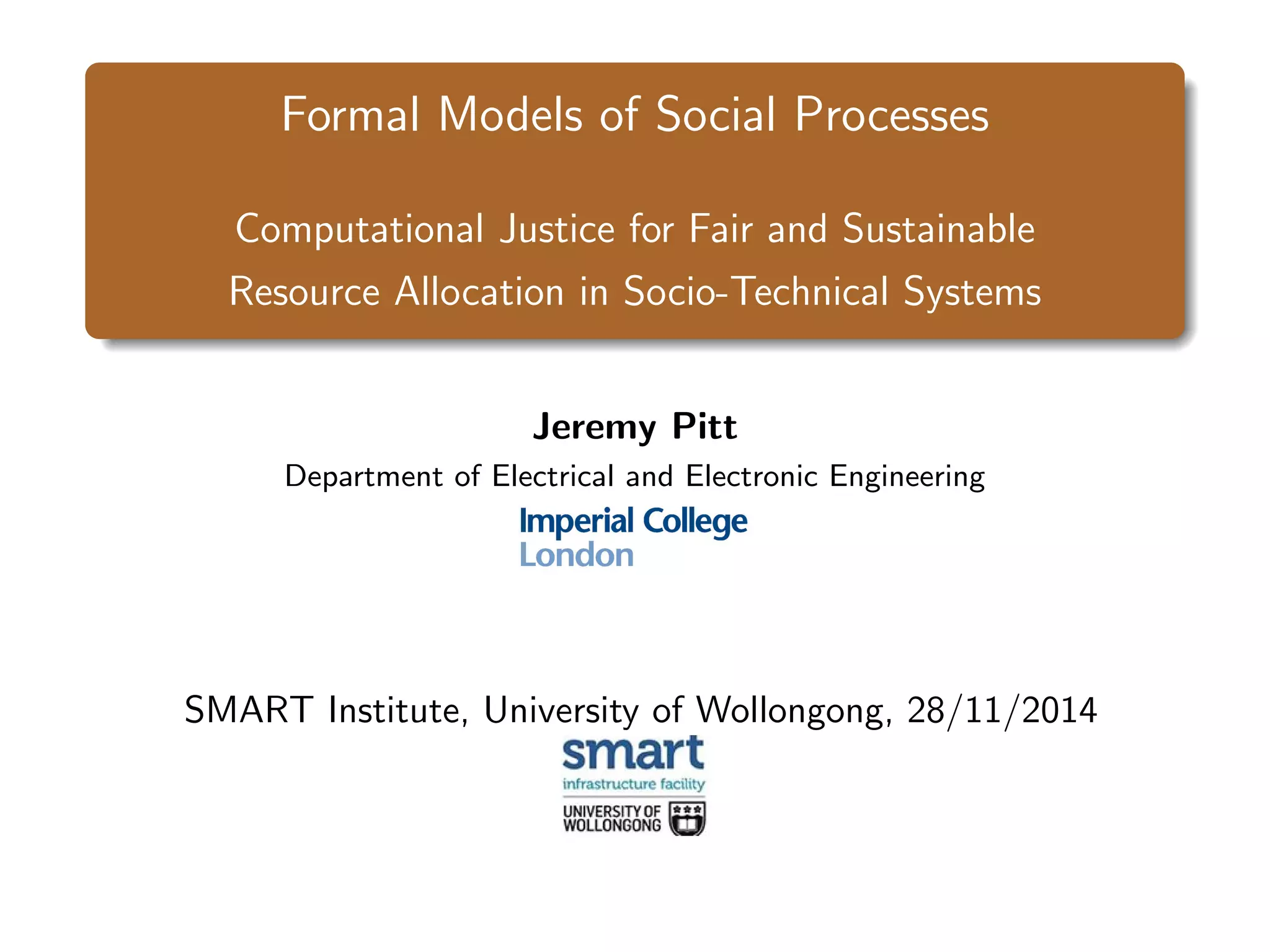

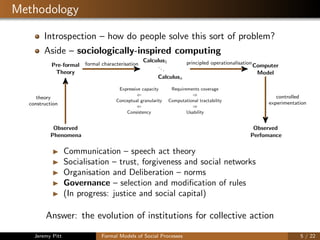

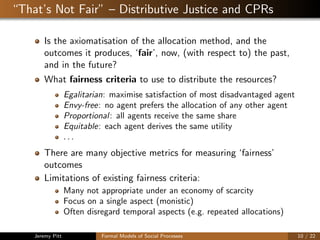

![Experimental Setting – Linear Public Good Game (LPG)

LPG commonly used to study free-riding in collective action

situations

Variant game: LPG – in each round, each agent:

Determines the resources it has available, gi ∈ [0, 1]

Determines its need for resources, qi ∈ [0, 1]

In an economy of scarcity, qi > gi

Makes a demand for resources, di ∈ [0, 1]

Makes a provision of resources, pi ∈ [0, 1] (pi ≤ gi )

Receives an allocation of resources, ri ∈ [0, 1]

Makes an appropriation of resources, ri ∈ [0, 1]

Agents may not comply, ri > ri

Utility in LPG : accrued resources Ri = ri + (gi − pi )

Ui =

aqi + b(Ri − qi ), if Ri ≥ qi

aRi − c(qi − Ri ), otherwise

Jeremy Pitt Formal Models of Social Processes 11 / 22](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/smartseminarseries-presentation-jeremypitt-141217214406-conversion-gate01/85/SMART-Seminar-Series-Formal-Models-of-Social-Processes-11-320.jpg)