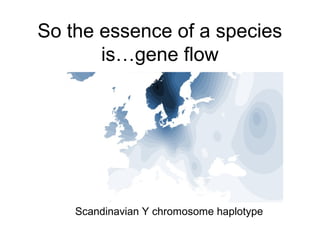

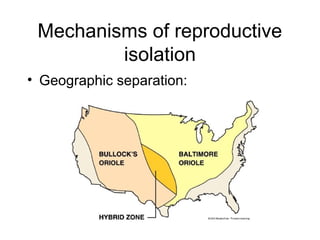

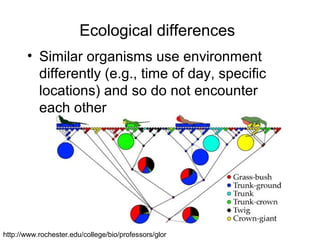

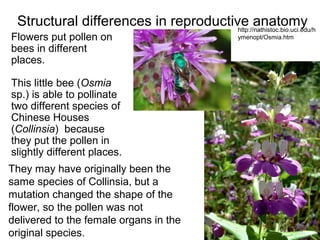

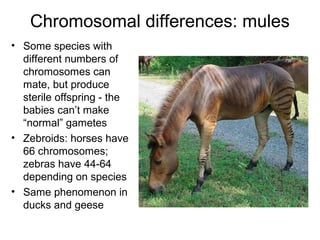

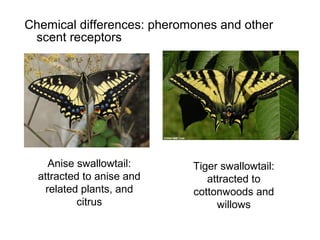

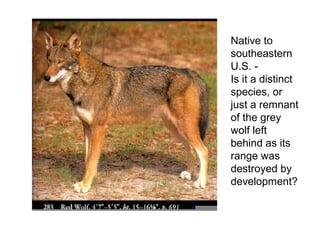

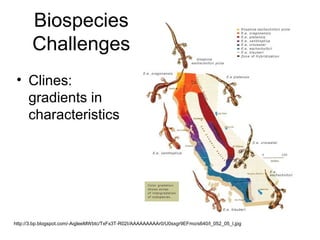

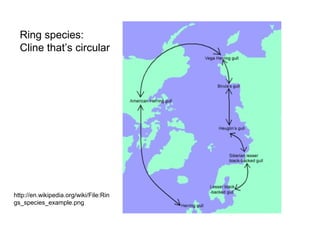

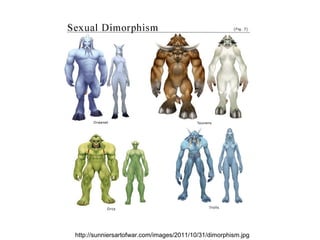

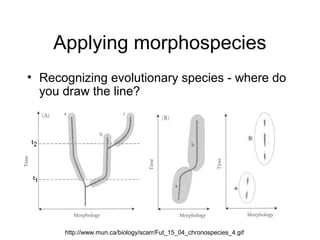

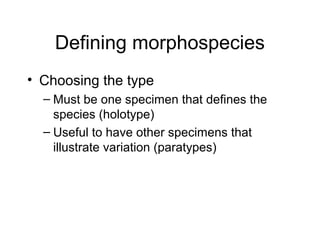

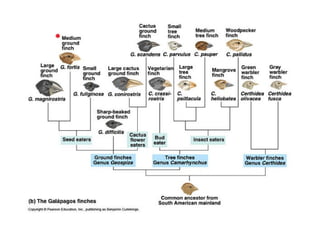

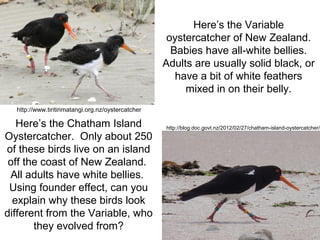

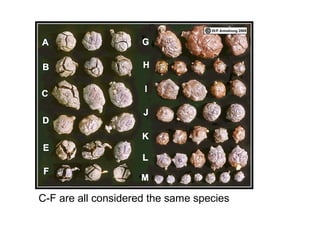

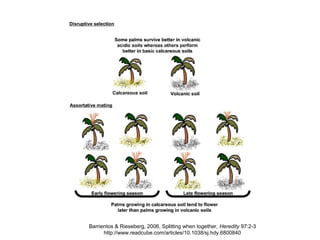

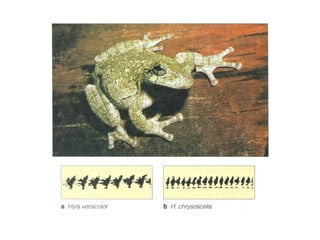

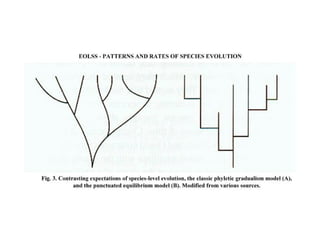

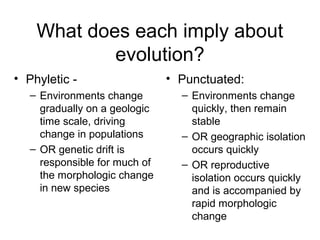

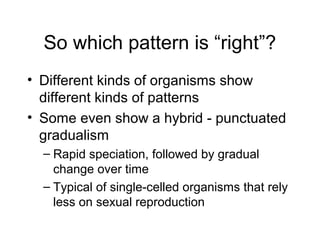

This document discusses the concept of biological species and mechanisms of reproductive isolation that can lead to speciation. It defines a biospecies as populations that interbreed and produce viable offspring, but are reproductively isolated from other such groups. Speciation can occur through geographic isolation (allopatric speciation) or within the same area (sympatric speciation) due to changes in chromosomes, anatomy, chemicals, ecology or behavior. The document also discusses challenges in defining species and patterns of evolutionary change, such as phyletic gradualism versus punctuated equilibrium.