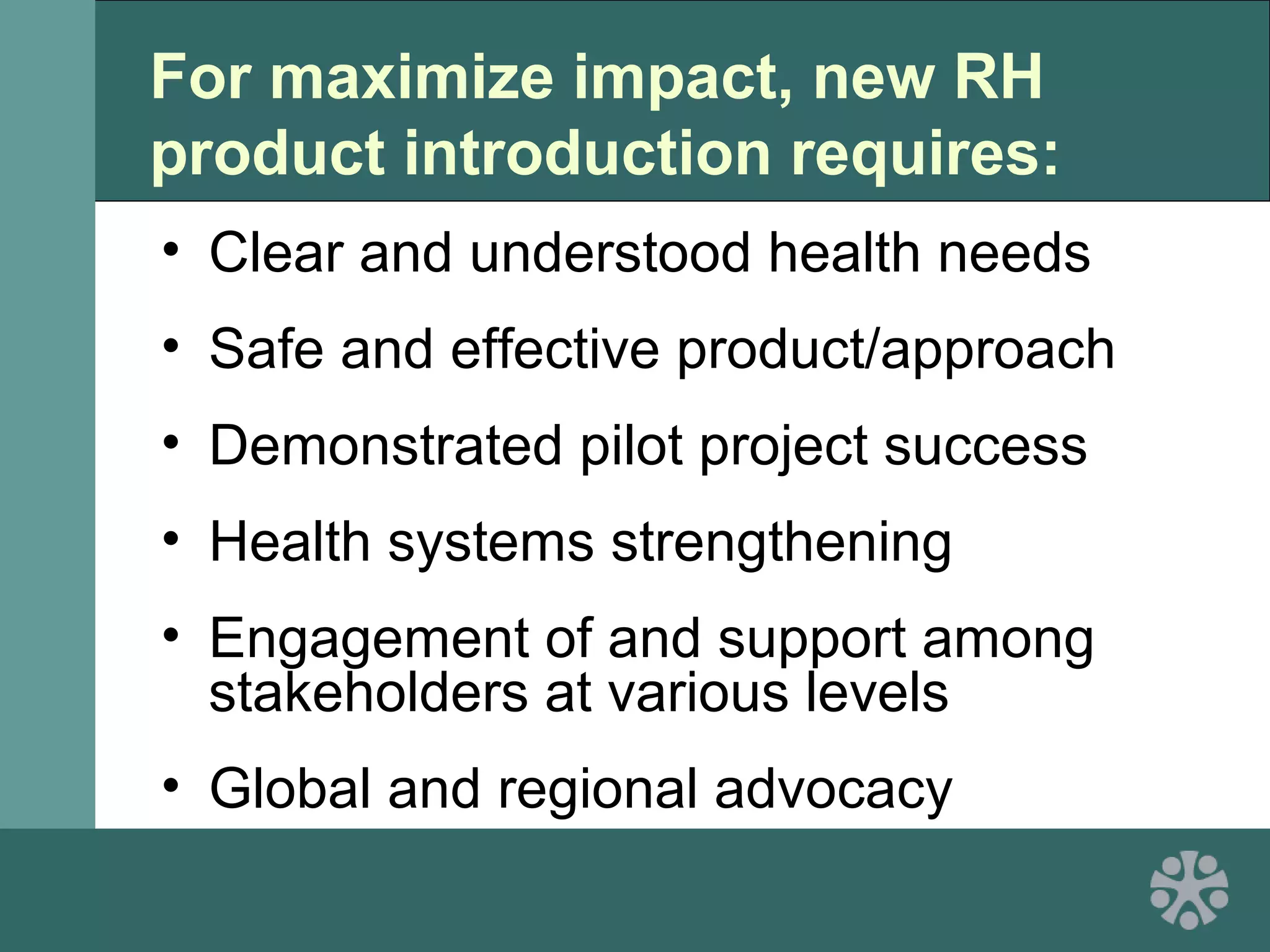

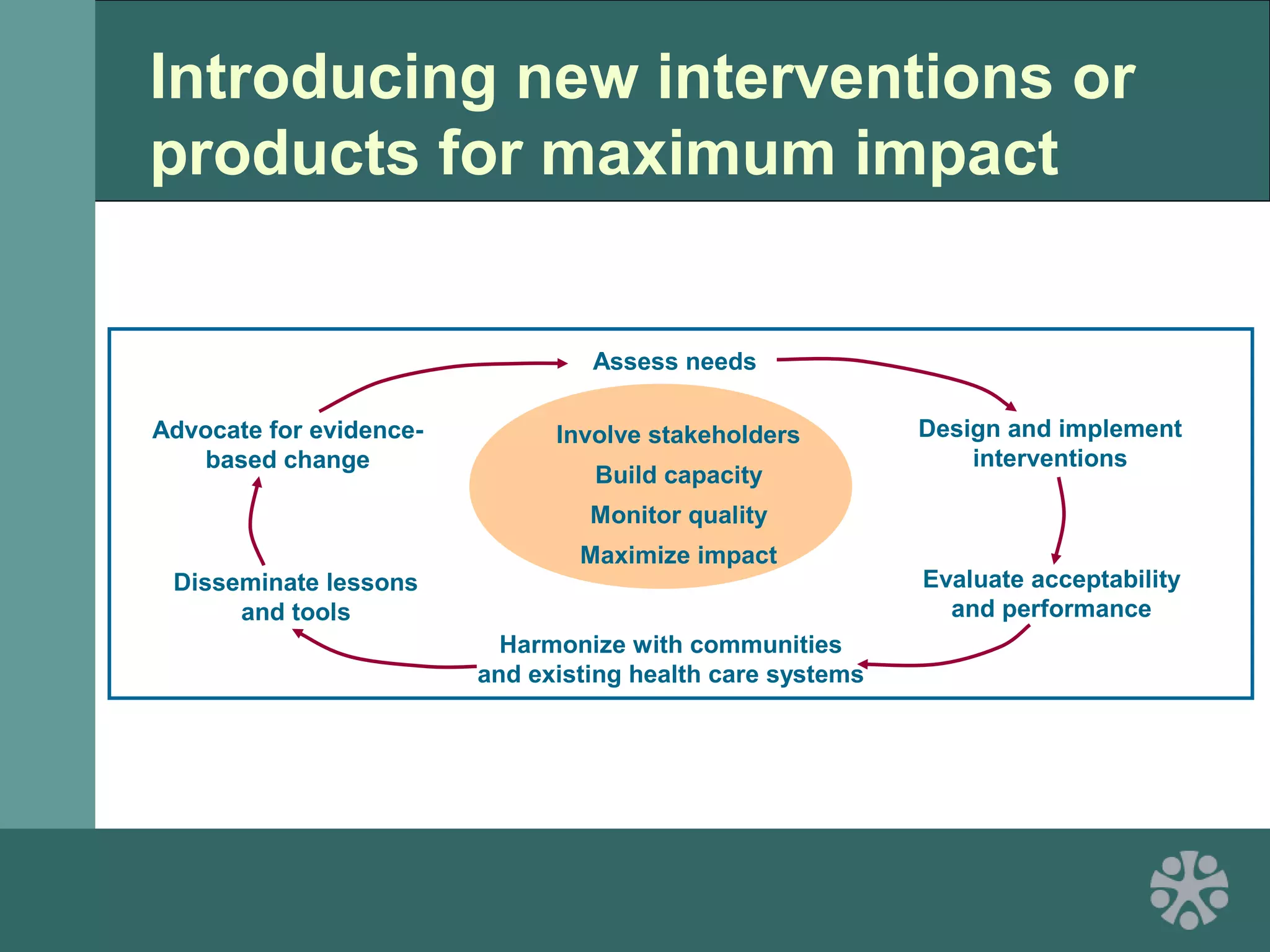

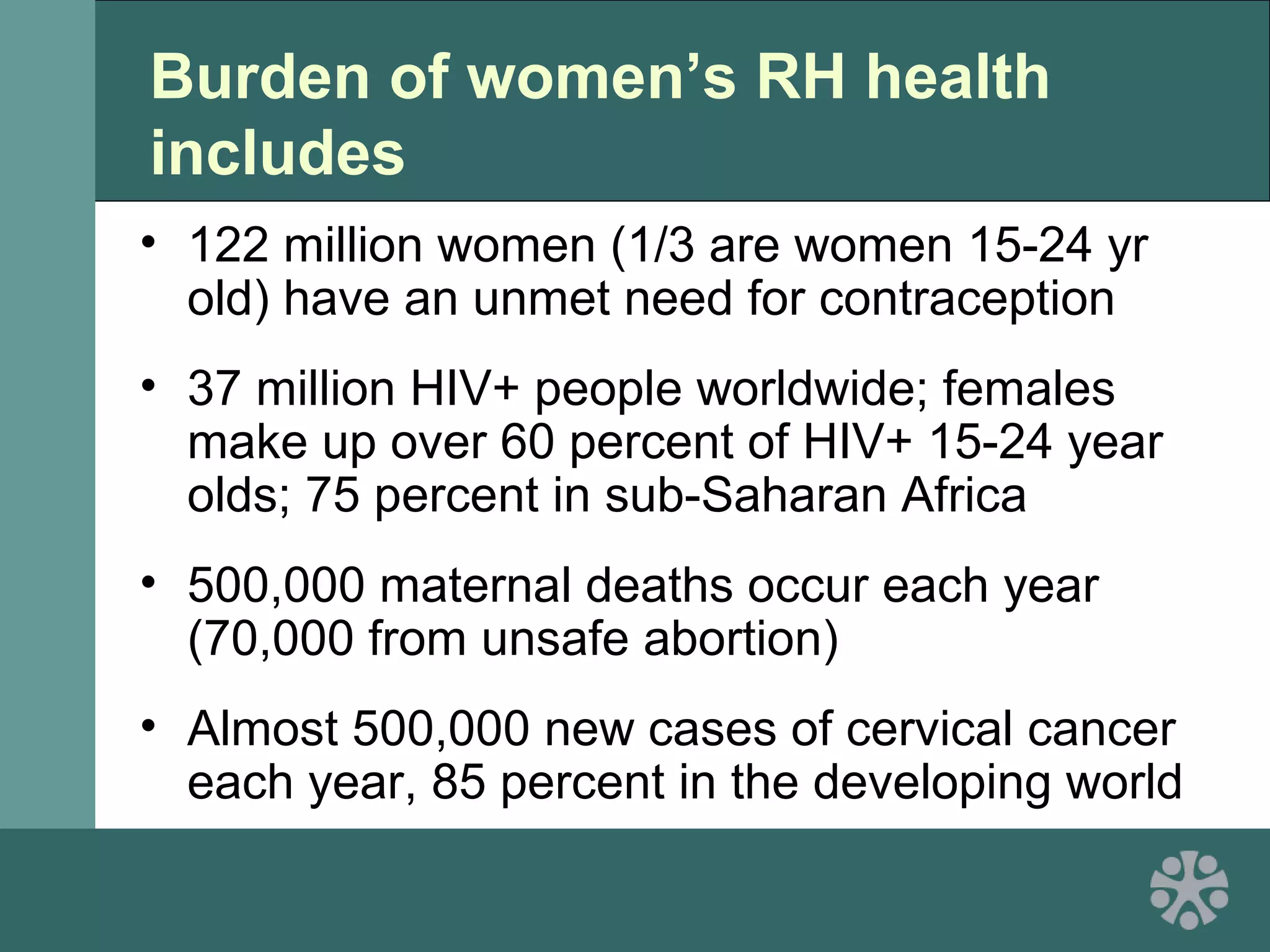

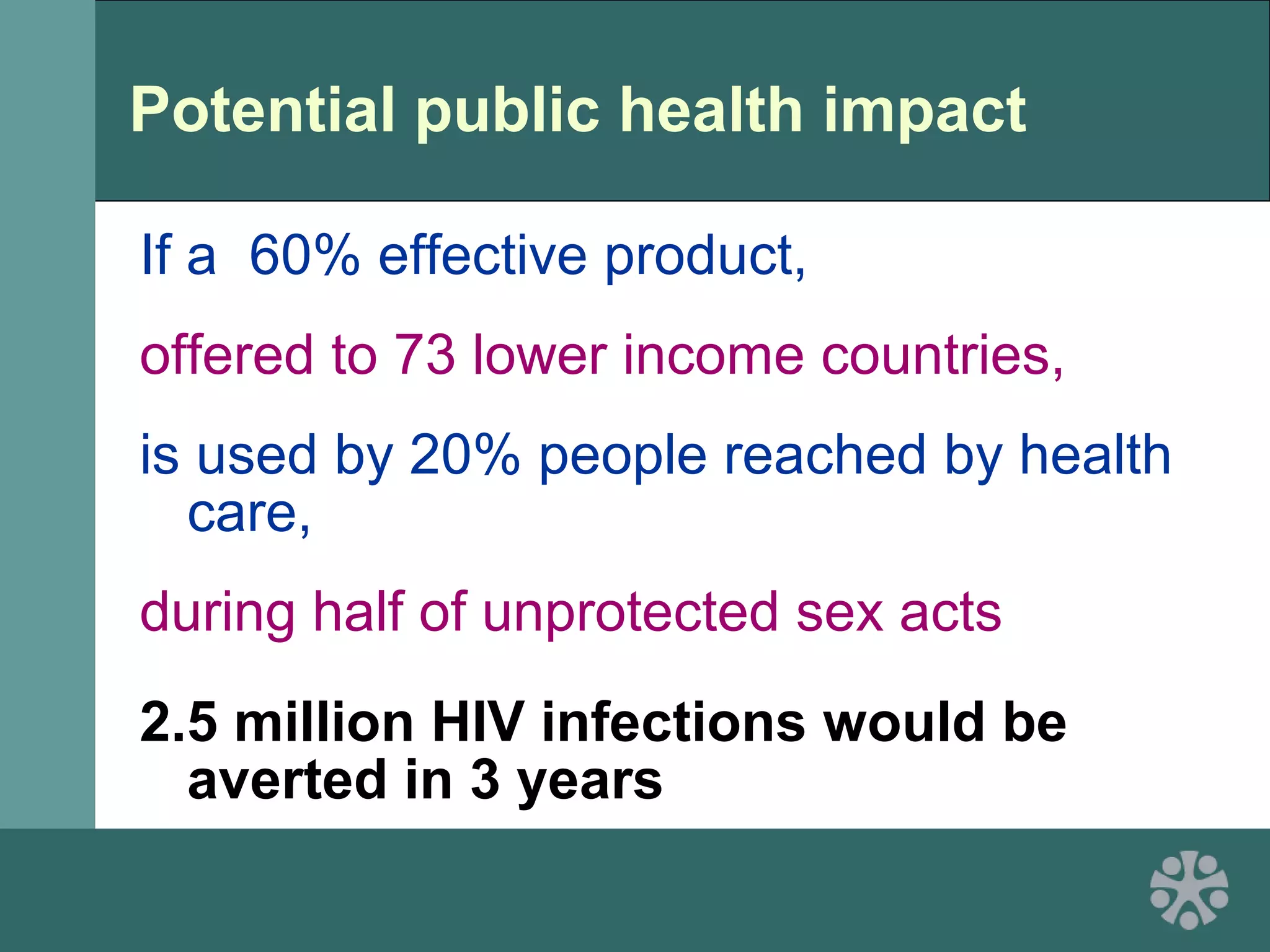

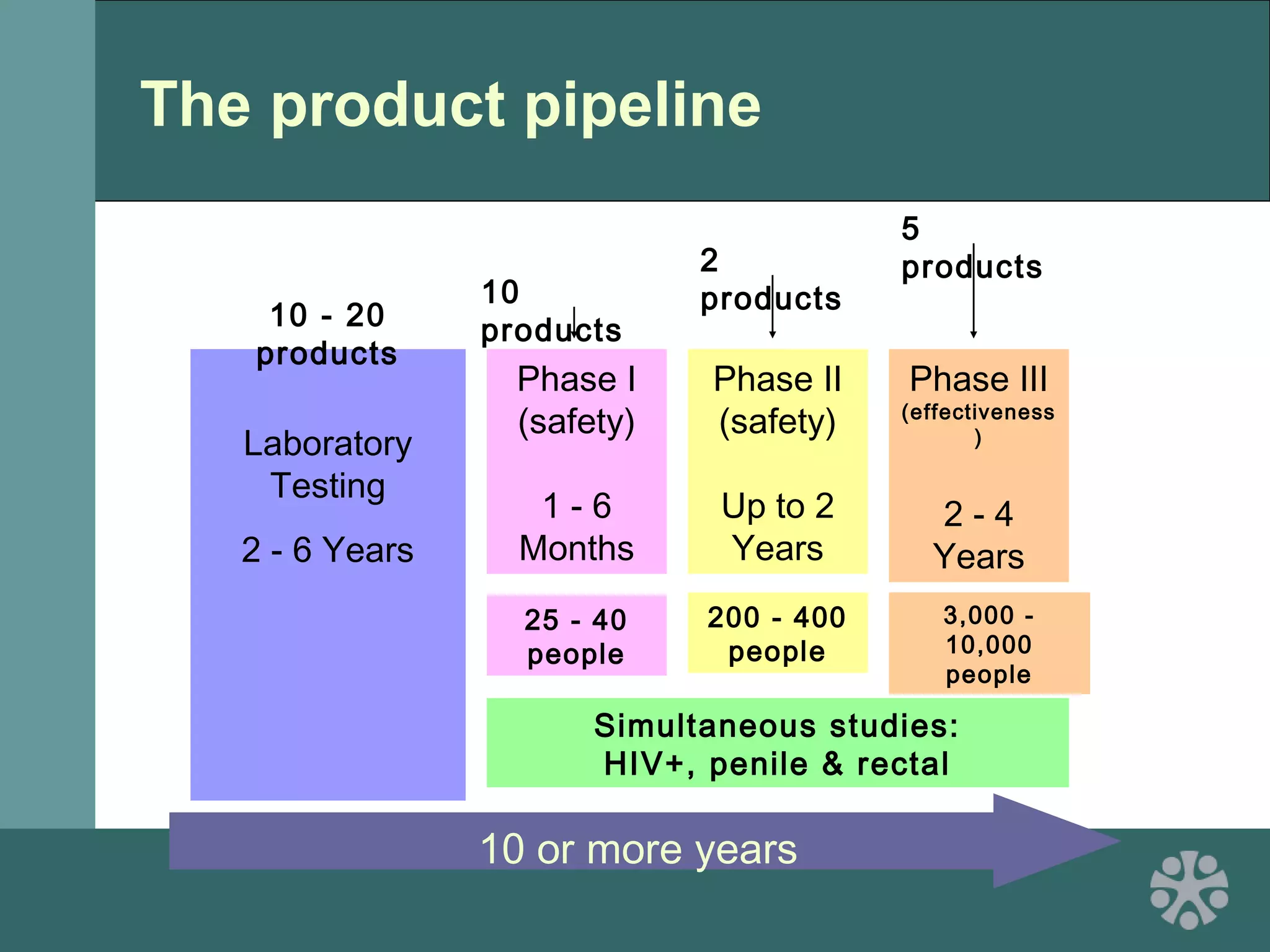

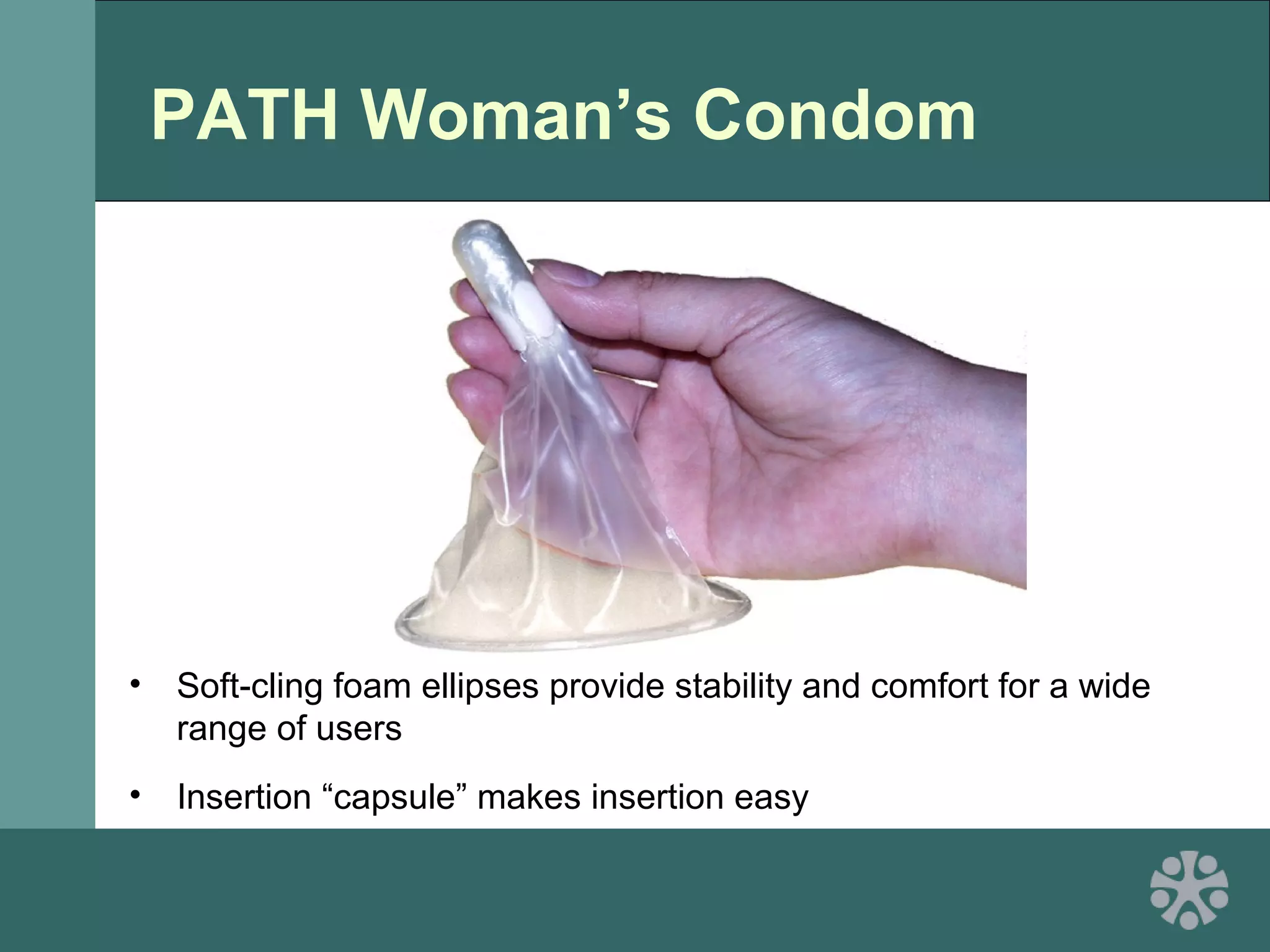

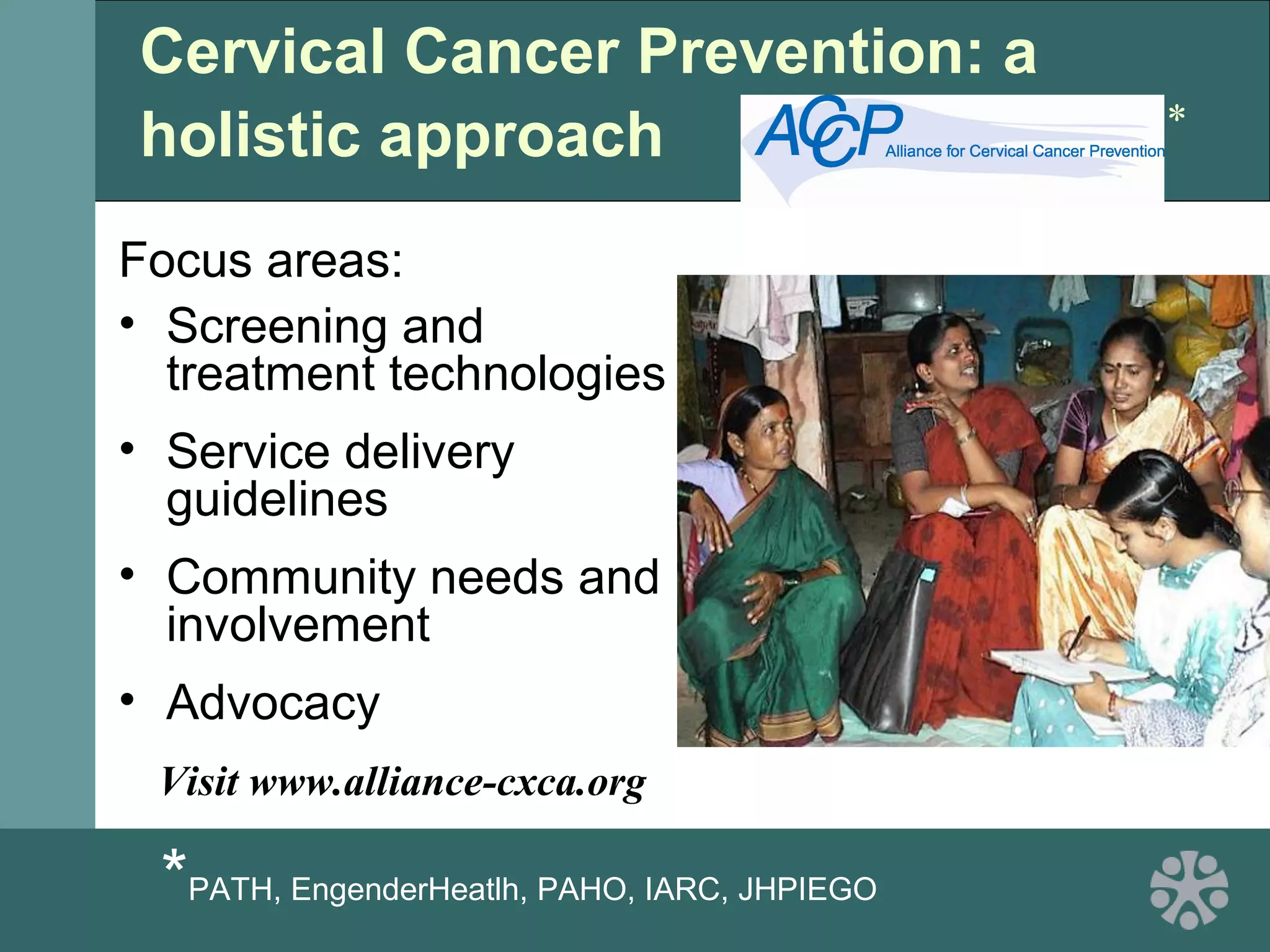

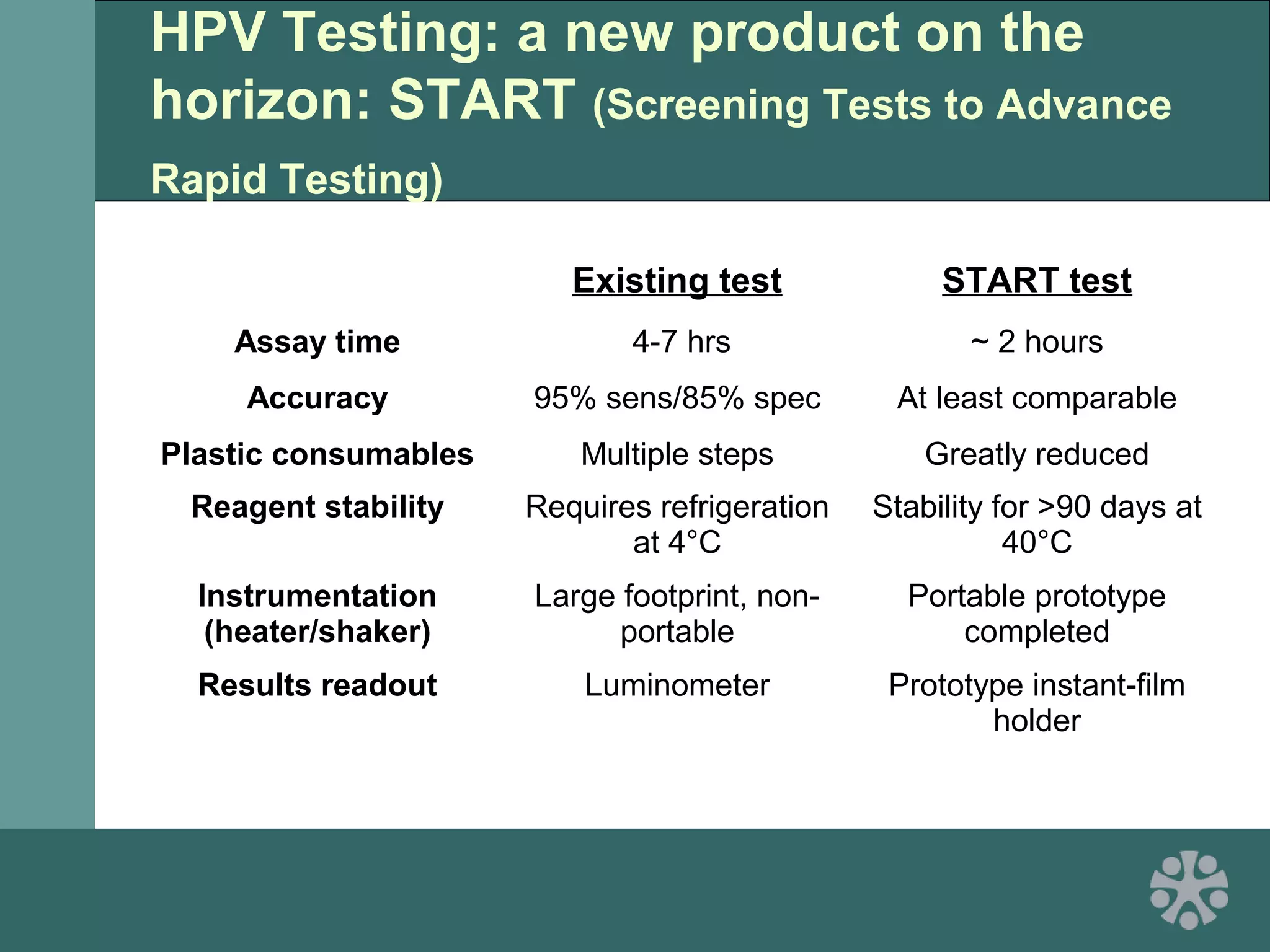

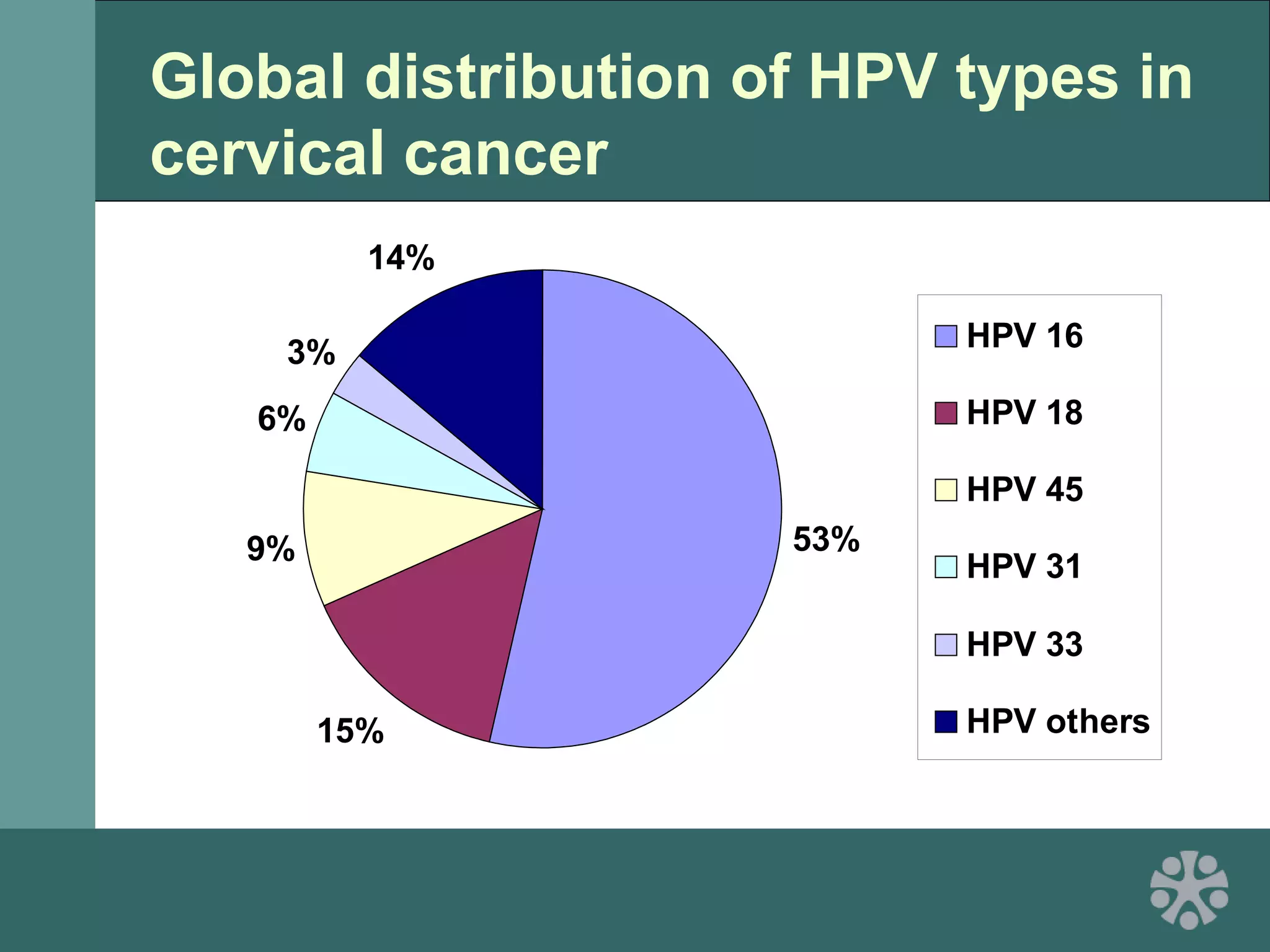

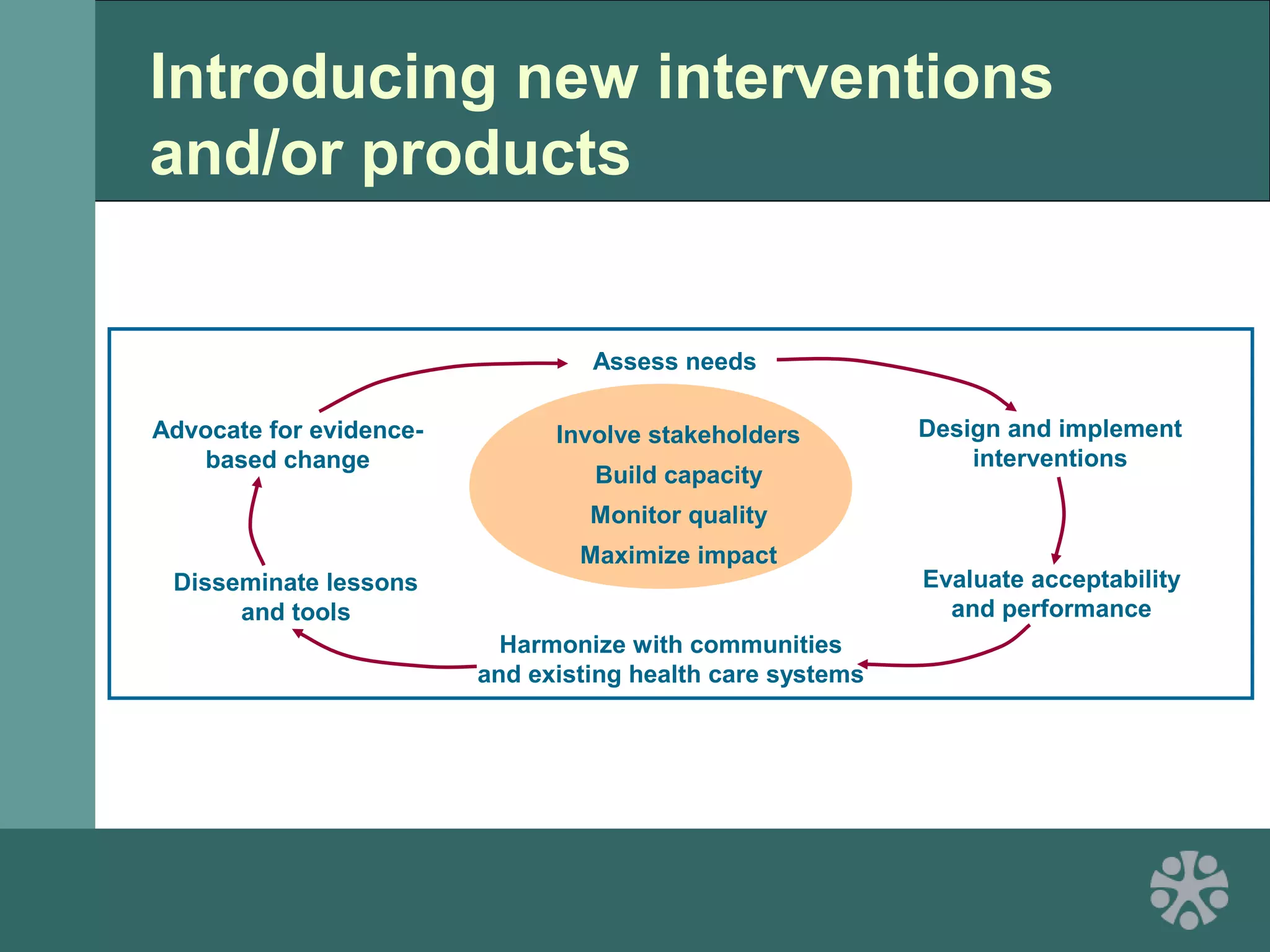

This document discusses strategies for improving women's reproductive health through expanding access to key health technologies. It outlines several approaches needed for successful introduction of new reproductive health products, including demonstrating pilot project success, health systems strengthening, and stakeholder engagement. The document then summarizes the burden of women's reproductive health issues and several underutilized technologies, such as microbicides, female barriers, emergency contraception, and cervical cancer prevention strategies. For each technology, it discusses research efforts, potential public health impacts, challenges to wider adoption, and strategies to increase impact and access.