This document discusses modeling and control of a 2 degree of freedom robot. It will:

1) Derive the forward and inverse kinematics of the robot using the proximal and distal D-H convention.

2) Calculate the Jacobian to relate joint velocities to end effector velocities.

3) Determine the dynamics of the robot using the Recursive Newton-Euler Formulation to calculate joint torques.

4) Generate a control scheme using these models to control the robot.

![Note that for diagram in Fig. 2, X1 does not fall on the link

of length a. As such, it is pertinent to invoke trigonometry

to introduce the following relationships:

𝑎1 = a ∗ sin (

𝜋

2

− 𝜂) = 𝑎 ∗ cos( 𝜂) (1)

𝑎2 = 𝑎 ∗ cos (

𝜋

2

− 𝜂) = 𝑎 ∗ sin( 𝜂) (2)

Based upon the above relationships, a1 is the distance

between x1 and the intersection of link 1/link 2 along the z2

axis and a2 is the distance between the z1 axis and z2 axis

along the x1 axis. Now, one can use the following set of

rules to fill out the D-H table:

1. Assign θn as the angle from xn-1 to xn measured

about zn.

2. Assign dn as the distance from xn-1 to xn measured

along zn

3. Assign an-1 as the distance from zn-1 to zn measured

along xn-1

4. Assign αn-1 as the angle from zn-1 to zn measured

about xn-1.

Using these, the following D-H table was generated

based upon the chosen coordinate frames:

Table 1: Proximal D-H Parameters

N θn dn an-1 αn-1

1 γ+π/2-η 0 0 0

2 0 d+a1 a2 π/2

From the D-H table, it is now possible to derive the

homogenous rotation matrices from one frame to another

using the following matrix in addition to the following

trigonometric relationships for theta:

cos (𝛾 +

𝜋

2

− 𝜂) = sin( 𝜂 − 𝛾) (3)

sin (𝛾 +

𝜋

2

− 𝜂) = cos( 𝜂 − 𝛾) (4)

And finally, the rotation matrices for each frame as well

as the overall homogenous rotation matrix from the base

frame to the end effector are as follows:

𝑡1 =0

[

s(η − γ) −𝑐(𝜂 − 𝛾) 0 0

𝑐(𝜂 − 𝛾) 𝑠(𝜂 − 𝛾) 0 0

0 0 1 0

0 0 0 1

]

𝑡2 =1

[

1 0 0 𝑎2

0 0 1 𝑑 + 𝑎1

0 −1 0 0

0 0 0 1

]

𝑡2 =0

[

𝑠(𝜂 − 𝛾) 0 𝑐(𝜂 − 𝛾) 𝑎2 𝑠(𝜂 − 𝛾) + (𝑑 + 𝑎1)𝑐(𝜂 − 𝛾)

𝑐(𝜂 − 𝛾) 0 −𝑠(𝜂 − 𝛾) 𝑎2 𝑐(𝜂 − 𝛾) − (𝑑 + 𝑎1)𝑠(𝜂 − 𝛾)

0 1 0 0

0 0 0 1

]

Using the above matrix and a computational device

(MATLAB), the position of the end effector can now be

plotted relative to arbitrary inputs for joint variables. For

example, gamma and d were both incremented by 0.01 (in

radians and inches, respectively) with the following path

being plotted:

Fig. 3. Robot end effector path for specified values of gamma and d

III. PART 2 – DISTAL D-H MODELING

Similar to the proximal modeling done above, the

distal D-H method is also used to find the end effector

position of a robot based upon given joint variables.

However, it differs in that now, the N-th+1 joint axes

when placing link frame origins. Due to this, one will now

arbitrarily place the 0-th link frame origin (generally so

that the math simplifies the most) and pick the N-th link

frame origin to match the N-th -1 link frame origin when

joint variable N is 0. Returning to Section II, this is the

inverse of the proximal D-H method. Shown below are

the coordinate frames used to complete the distal D-H

modeling.

Fig. 4. Distal D-H Coordinate Frames applied to the given 2 DOF

Robotics Platform](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ac953a11-bf44-4012-a03d-e0de85935020-160408015616/75/Robotics_Final_Paper_Folza-2-2048.jpg)

![Invoking the same trigonometric properties as in

section II, the following rules can be used to fill out a D-H

table:

1. Assign θn+1 as the angle from xn to xn+1 measured

about zn.

2. Assign dn+1 as the distance from xn to xn+1

measured along zn

3. Assign an+1 as the distance from zn to zn+1 measured

along xn+1

4. Assign αn+1 as the angle from zn to zn+1 measured

about xn+1.

Using these, the following D-H table was generated

based upon the chosen coordinate frames:

Table 2: Distal D-H Parameters

N θn dn an-1 αn-1

0 γ+π/2-η 0 a2 π/2

1 0 d+a1 0 0

Since the rules for defining each value in the D-H table

has changed from the proximal method, so too does the

homogenous transformation matrix that can be used to go

from one frame to another. This “new” matrix is as below:

And finally, the rotation matrices for each frame as well

as the overall homogenous rotation matrix from the base

frame to the end effector are as follows:

𝑡1 =0

[

s(η − γ) 0 𝑐(𝜂 − 𝛾) 𝑎2 𝑠(𝜂 − 𝛾)

𝑐(𝜂 − 𝛾) 0 −𝑠(𝜂 − 𝛾) 𝑎2 𝑐(𝜂 − 𝛾)

0 1 0 0

0 0 0 1

]

𝑡2 =1

[

1 0 0 0

0 1 1 0

0 0 1 𝑑 + 𝑎1

0 0 0 1

]

𝑡2 =0

[

𝑠(𝜂 − 𝛾) 0 𝑐(𝜂 − 𝛾) 𝑎2 𝑠(𝜂 − 𝛾) + (𝑑 + 𝑎1)𝑐(𝜂 − 𝛾)

𝑐(𝜂 − 𝛾) 0 −𝑠(𝜂 − 𝛾) 𝑎2 𝑐(𝜂 − 𝛾) − (𝑑 + 𝑎1)𝑠(𝜂 − 𝛾)

0 1 0 0

0 0 0 1

]

Since the final homogeneous rotation matrix from the

base frame to the end effector matches the matrix from

Section II (proximal DH), a plot showing the path of the

end effector of the robot using the above matrix would

match the plot shown in Fig. 3.

IV. PART 3 – INVERSE KINEMATICS

Having confirmed the validity of the forward

kinematics through the comparison of distal results with

proximal results, it is now possible to find the inverse

kinematics of the robot. This can be done setting the final

homogeneous rotation matrix equal to the NOA matrix as

shown below:

[

𝑛 𝑥 𝑜 𝑥 𝑎 𝑥 𝑃𝑥

𝑛 𝑦 𝑜 𝑦 𝑎 𝑦 𝑃𝑦

𝑛 𝑧 𝑜_𝑧 𝑎_𝑧 𝑃𝑧

0 0 0 1

]

=[

𝑠(𝜂 − 𝛾) 0 𝑐(𝜂 − 𝛾) 𝑎2 𝑠(𝜂 − 𝛾) + (𝑑 + 𝑎1)𝑐(𝜂 − 𝛾)

𝑐(𝜂 − 𝛾) 0 −𝑠(𝜂 − 𝛾) 𝑎2 𝑐(𝜂 − 𝛾) − (𝑑 + 𝑎1)𝑠(𝜂 − 𝛾)

0 1 0 0

0 0 0 1

]

Now, observe the fourth column of the matrix to

generate the following set of equations:

𝑃𝑥 = 𝑎2 𝑠(𝜂 − 𝛾) + (𝑑 + 𝑎1)𝑐(𝜂 − 𝛾) (5)

𝑃𝑦 = 𝑎2 𝑐(𝜂 − 𝛾) − (𝑑 + 𝑎1)𝑠(𝜂 − 𝛾) (6)

𝑃𝑧 = 0 (7)

Finally, use algebra to generate two equations that

solve for d and γ independently in terms of Px and Py.

Begin by solving for d in Eqs. (5 & 6) as shown below,

noting that 𝛽 = 𝜂 − 𝛾:

𝑑 =

(𝑥−𝑎2∗sin(𝛽)−𝑎1∗cos(𝛽))

𝑐𝑜𝑠(𝛽)

(5a)

𝑑 =

(−𝑦+𝑎2∗cos(𝛽)−𝑎1∗sin(𝛽))

𝑠𝑖𝑛(𝛽)

(6a)

Now, if Eqs. (5a & 6a) are set equal to one another, it is

possible to solve for beta in terms of x & y independently

of d.

(−𝑦+𝑎2∗cos(𝛽)−𝑎1∗sin(𝛽))

𝑠𝑖𝑛(𝛽)

=

(−𝑦+𝑎2∗cos(𝛽)−𝑎1∗sin(𝛽))

𝑠𝑖𝑛(𝛽)

(8)

Or:

𝑥 ∗ sin(𝛽) + 𝑦 ∗ cos(𝛽) = 𝑎2 (8a)

Finally, to solve for beta, trig properties can be invoked

or it can be solved using a symbolic mathematics

solver such as maple or Wolfram Alpha. Using Wolfram

Alpha yields:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ac953a11-bf44-4012-a03d-e0de85935020-160408015616/75/Robotics_Final_Paper_Folza-3-2048.jpg)

![𝛽 = 2 ∗ tan−1

(

𝑥−𝑠𝑞𝑟𝑡(−𝑎2

2+𝑥2+𝑦2)

𝑎2+𝑦

) (9)

Having solved for beta, it can now be subbed back into

either Eq. (5a) or Eq. (6a) to solve for d. This completes

the inverse kinematic solution for the robot.

V. PART 4 – JACOBIAN & INVERSE JACOBIAN

Now that the position of the end effector of the robot

is fully defined through the use of forward and inverse

kinematics, it is now time to define the time derivative of

position, velocity, of the end effector of the robot in

terms of the velocities of the joints and vice versa. The

Jacobian and inverse Jacobian can be employed to handle

this task. In general, the Jacobian is defined by the

following function:

Applying this function to the 2 DOF robot presented

yields the following matrix based relationship between

end effector velocities and joint velocities:

[

𝑥̇

𝑦̇

] = [

𝐽11

𝑇0

𝐽12

𝑇0

𝐽21

𝑇0

𝐽22

𝑇0

] [

𝛾̇

𝑑̇

] (10)

However, the Jacobian must first be found in the end

effector frame. Since this will be multiplied through by

the rotation matrix, all 6 values in each of the columns of

the Jacobian must be found. This can be done with the

following set of equations:

𝐽11

𝑇2

= (−𝑛 𝑥 𝑝 𝑦 + 𝑛 𝑦 𝑝 𝑥) (11)

𝐽12

𝑇2

= (−𝑜 𝑥 𝑝 𝑦 + 𝑜 𝑦 𝑝 𝑥) (12)

𝐽13

𝑇2

= (−𝑎 𝑥 𝑝 𝑦 + 𝑎 𝑦 𝑝 𝑥) (13)

𝐽14

𝑇2

= (𝑛 𝑧) (14)

𝐽15

𝑇2

= (𝑜𝑧) (15)

𝐽16

𝑇2

= (𝑎 𝑧) (16)

𝐽21

𝑇2

= (𝑛 𝑧) (17)

𝐽22

𝑇2

= (𝑜𝑧) (18)

𝐽23

𝑇2

= (𝑎 𝑧) (19)

𝐽24

𝑇2

= (0) (20)

𝐽25

𝑇2

= (0) (21)

𝐽26

𝑇2

= (0) (22)

Using values from the NOA matrix as shown below, it is

now possible to solve for each value in the J matrix:

[

𝑛 𝑥 𝑜 𝑥 𝑎 𝑥 𝑃𝑥

𝑛 𝑦 𝑜 𝑦 𝑎 𝑦 𝑃𝑦

𝑛 𝑧 𝑜𝑧 𝑎 𝑧 𝑃𝑧

0 0 0 1

] =

[

𝑠(𝜂 − 𝛾) 0 𝑐(𝜂 − 𝛾) 𝑎2 𝑠(𝜂 − 𝛾) + (𝑑 + 𝑎1)𝑐(𝜂 − 𝛾)

𝑐(𝜂 − 𝛾) 0 −𝑠(𝜂 − 𝛾) 𝑎2 𝑐(𝜂 − 𝛾) − (𝑑 + 𝑎1)𝑠(𝜂 − 𝛾)

0 1 0 0

0 0 0 1

]

Plugging in all 12 values required yields the following

matrix:

𝐽 =

𝑇2

[

𝑑 + 𝑎1 0

0 0

−𝑎2 1

0 0

1 0

0 0]

To find the Jacobian in the base frame (useful for finding

joint velocities and singularities), it will be required to

multiply the Jacobian in the end effector frame by the

rotation transformation matrix from the end effector frame

to the base frame in the following form in Eq. (23):

𝐽 =

𝑇0

[

𝑅2

0

0 0 0

0 0 0

0 0 0

0 0 0

0 0 0

0 0 0

𝑅2

0

]

𝐽

𝑇2

(23)

Completing this multiplication yields the Jacobian in the

base frame. The Jacobian relates known velocities in joint

space (in this case, the derivatives of gamma and d) to

velocities in cartesian (or cylindrical, spherical, etc.) space.

This was shown in Eq. (10). Subbing in values of the first two

rows found in Eq. (23) (as this robot only has 2 DOF) yields

the following:

[

𝑥̇

𝑦̇

] = [

(𝑎1 + 𝑑) sin(𝜂 − 𝛾) − 𝑎2cos( 𝜂 − 𝛾) cos( 𝜂 − 𝛾)

(𝑎1 + 𝑑) cos(𝜂 − 𝛾) + 𝑎2sin( 𝜂 − 𝛾) sin(𝜂 − 𝛾)

] [

𝛾̇

𝑑̇

]

(10a)

In addition, it will be useful to find the inverse Jacobian

matrix, which relates input joint velocities to end effector

velocities and is as follows:

[

𝛾̇

𝑑̇

]

=

1

−(𝑎1 + 𝑑)

[

sin( 𝜂 − 𝛾) −cos( 𝜂 − 𝛾)

−(𝑎1 + 𝑑) cos(𝜂 − 𝛾) − 𝑎2sin( 𝜂 − 𝛾) (𝑎1 + 𝑑) sin(𝜂 − 𝛾) − 𝑎2cos( 𝜂 − 𝛾)

] [

𝑥̇

𝑦̇

]

(10b)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ac953a11-bf44-4012-a03d-e0de85935020-160408015616/75/Robotics_Final_Paper_Folza-4-2048.jpg)

![Finally, singularities can be found using the determinate

of the Jacobian in the 0 frame. This will be useful to

determine locations at which infinite joint velocities will be

needed to achieve certain end effector velocities. In a

practical application, these positions should be avoided if at

all possible.

det( 𝐽) = 0

𝑇0

(24)

𝑑 = −𝑎1

VI. PART 5 –DYNAMIC ANALYSIS USING RECURSIVE

NEWTON-EULER FORMULATION

With the velocity analysis of the 2 DOF robot now

complete, it is possible to move on to the acceleration

and force (dynamic) analysis of the robot. To do so, the

recursive Newton-Euler (RNE) formulation will be

employed. The RNE approach to dynamic modeling is a

computer programmable way of finding the dynamics of

a system by using an algorithmic-based set of coordinate

frames. Often times, it is used on multi DOF systems as

the dynamic analysis of systems rapidly becomes more

complex as the number of DOF increases. Begin this

method by recalling the rotation matrices (as well as the

coordinate systems as seen in Fig. 4) generated from the

Distal Variant D-H procedure completed earlier:

𝐴1 = [

s(η − γ) 0 𝑐(𝜂 − 𝛾) 𝑎2 𝑠(𝜂 − 𝛾)

𝑐(𝜂 − 𝛾) 0 −𝑠(𝜂 − 𝛾) 𝑎2 𝑐(𝜂 − 𝛾)

0 1 0 0

0 0 0 1

]

𝐴2 = [

1 0 0 0

0 1 1 0

0 0 1 𝑑 + 𝑎1

0 0 0 1

]

The transposed 3x3 rotation matrix from each will be

used extensively through the remainder of the analysis.

Working up towards finding the torque or force applied by

each joint, begin by finding the angular velocity at each

joint (note that for each step, equations will differ when

observing a prismatic joint vs. a revolute joint):

𝜔⃑⃑ 1 = 𝑅0( 𝜔⃑⃑0

0 + [

0

0

1

] 𝛾)̇11

(25)

𝜔⃑⃑ 1 =[

0

𝛾̇

0

]1

𝜔⃑⃑ 2 = 𝑅1( 𝜔⃑⃑1

1)22

(26)

𝜔⃑⃑ 2 =[

0

𝛾̇

0

]2

Similarly, to find the angular acceleration of each joint:

𝛼1 = 𝑅0( 𝛼0

0 + ⌈

0

0

1

⌉11

𝛾̈ + 𝜔⃑⃑0

0 𝑋 [

0

0

1

] 𝛾̇) (27)

𝛼1 =[

0

𝛾̈

0

]1

𝛼1 = 𝛼2

2

=[

0

𝛾̈

0

]1

Next, to find the radius to each coordinate system and

the linear velocity of each:

𝑟𝑖

𝑖

= [

𝑎𝑖

𝑑𝑖sin( 𝛼𝑖)

𝑑𝑖cos(αi)

] (28)

𝑟1

1

= [

𝑎2

0

0

]

𝑟2

2

= [

0

0

𝑑 + 𝑎1

]

𝑣1 = 𝑅1

01

𝑣0

0 + 𝜔⃑⃑ 1𝑥 𝑟1

11

(29)

𝑣1 = [

0

0

−𝑎2 𝛾̇

]1

𝑣2 = 𝑅2

12

( 𝑣1

1 + [

0

0

1

] 𝑑̇2) + 𝜔⃑⃑ 2𝑥 𝑟2

22

(30)

𝑣2 = [

𝛾̇( 𝑑 + 𝑎1)

0

𝑑̇ − 𝑎2 𝛾̇

]2

At this point, the equations in use became exceedingly

complex. As such, MATLAB was used to assist in the

calculation of each successive step in the RNE method.

However, the calculations for each of these steps can be

seen in the RNE formulation code found in Appendix A of

this report. Looking at the final step, the Equations of

motion (depicted in matrix form) are as below:

𝑚(𝜃̈)

= [ 𝑚1 (

1

4

𝑎2

) + 𝑚2(𝐿2

2

− 2𝐿2(𝑎 + 𝑑) + 𝑎2

+ 2𝑎1 𝑑 + 𝑑2) + 𝐼1 + 𝐼2 −𝑚2 𝑎2

−𝑚2 𝑎2 𝑚2

]

(31)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ac953a11-bf44-4012-a03d-e0de85935020-160408015616/75/Robotics_Final_Paper_Folza-5-2048.jpg)

![𝑣(𝜃, 𝜃̇) = [

2𝑚2(𝑎1 + 𝑑 − 𝐿2)𝑑̇ 𝛾̇

−𝑚2(𝑎1 + 𝑑 + 𝐿2)𝛾̇2

] (32)

𝑔(𝜃) = [

𝑚1 𝐿1 cos(−𝛾) + 𝑚1 𝑎(sin(𝜂 − 𝛾) (sin(𝜂) − sin(𝛾))) + 𝑚2 cos(𝜂 − 𝛾) (𝑎1 − 𝑑 + 𝐿2) + 𝑚2 𝑎2sin( 𝜂 − 𝛾)

𝑚2sin( 𝛾 − 𝜂)

]

(33)

To see Eqs. (31-33) in full size text, please see Appendix B

at this end of this report. Looking to the usefulness of the

forward dynamics, they can be used in conjunction with a

numerical integrator (ode45, 1st

order Euler integration,

etc.) to solve for joint positions and velocities based upon

past joint positions and velocities as well as an input torque.

A model for this is as shown below. This is critical for

implementing a controller on a robot and will be used in

Section IX, robot control.

𝑑

𝑑𝑡

{𝜃} = {

{𝑞̇}

[𝑚]−1

(𝑣 + 𝑔 + 𝑇𝑎𝑢)

} (34)

𝜃 = {

𝑞

𝑞̇} (35)

VII. PART 6- INVERSE DYNAMIC ANALYSIS

Previously, forward dynamics were found and are used

to determine unknown joint parameters based upon

previously known joint parameters and a known input

torque. Inversely of this (pardon the pun), inverse

dynamics are used to take known input joint parameters

and determine required joint torques to meet these

parameters. It is also based upon the equations of

motion found in Section VI and is as follows:

[

𝜏1

𝐹2

] = 𝑚(𝜃̈) [

𝛾̈

𝑑̈

] + 𝑣(𝜃, 𝜃̇) + 𝑔(𝜃)𝑔 (36)

To solve for Tau1 and F2, plug in the matrices in Eqs.

(31-33) into Eq. (36) Theoretically, Eq. (36) would be able

to be used to output known joint torques for a desired

trajectory and, essentially, “drive” a robot. However, with

errors caused by assumptions made and modeling

uncertainty (in addition to the possibility of a disturbance

load being applied), it would be very likely that some

error would exist by doing this. Hence the existence of

Section IX, robot control.

VIII. PART 7 – TRAJECTORY PLANNING

At this point, all parameters for the motion or the 2

DOF robot are able to be solved from the work done in

Section II through Section VII. However, this work isn’t

executable unless a set of input conditions is calculated.

This is where trajectory planning comes in. In most

applications, it will be desired for either the output

position or the output velocity in Cartesian space to be

controlled.

In the case of the 2 DOF robot being investigated, the

use of the robot is for welding. In this scenario, it is

desired for the robot to travel along a straight path (the

weld path) at a constant velocity such that the weld is

consistent. This can be translated into a velocity vector,

with the magnitude being the velocity and angle being

the direction of the straight-line path. In addition, the end

time of the move will also be treated as an input and it is

known that the start and end velocity of the end effector

must be zero.

To complete this objective, a parabolic blend approach

was utilized. While this approach was taught in terms of

the joint space, it will be desired to use the approach in

the Cartesian space for this application with the end

effector velocity during the linear portion of the path

being equal to the desired velocity. Desired velocities in

Cartesian space can be found from the velocity vector as

shown below:

𝑣𝑥 = 𝑣̇ ∗ cos( 𝜈) (37)

𝑣 𝑦 = 𝑣̇ ∗ sin(𝜈)(38)

To find the x and y trajectory of the robot end effector

at all times of the move, the following piecewise function

will be used:

𝑥 =

{

𝑥𝑖 +

1

2

𝑣 𝑥

𝑡 𝑏

∗ 𝑡2

𝑓𝑜𝑟𝑡 < 𝑡 𝑏

𝑥𝑖 +

1

2

𝑥̇ 𝑡 𝑏 + 𝑥(𝑡𝑓 − 2𝑡 𝑏)𝑓𝑜𝑟𝑡𝑏 ≤ 𝑡 ≤ 𝑡𝑓 − 𝑡 𝑏

𝑥𝑓 −

1

2

𝑣 𝑥

𝑡 𝑏

∗ (𝑡𝑓 − 𝑡)

2

𝑓𝑜𝑟𝑡 > 𝑡𝑓 − 𝑡 𝑏

(39)

Note that to solve for y, simply substitute each x and vx

in Eq. (39) with y and vy. In addition, it is easy to note

that there are still several unknowns on the right side of

Eq. (39) in the form of tb, xi and xf. Start by also treating tb

of the system as an input. This can be adjusted to change

the maximum acceleration of the end effector during the

move. In addition, xi can be found by running the initial

joint positions through the forward kinematics of the

robot. Finally, xf is defined by the following equation:

𝑥𝑓 = 𝑥𝑖 + 𝑥̇( 𝑡𝑓 − 𝑡 𝑏) (40)

Now, with the x and y trajectory of the robot defined, it is

possible to use the functions previously developed to find

the rest of the system parameters. For example, using x and

y in conjunction with the inverse kinematics to find gamma

and d. However, to find acceleration characteristics, the

following function will be used:

𝜃̈ =

(𝜃̇ 𝑐𝑢𝑟𝑟𝑒𝑛𝑡−𝜃̇ 𝑝𝑟𝑒𝑣)

Δ𝑡

(42)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ac953a11-bf44-4012-a03d-e0de85935020-160408015616/75/Robotics_Final_Paper_Folza-6-2048.jpg)

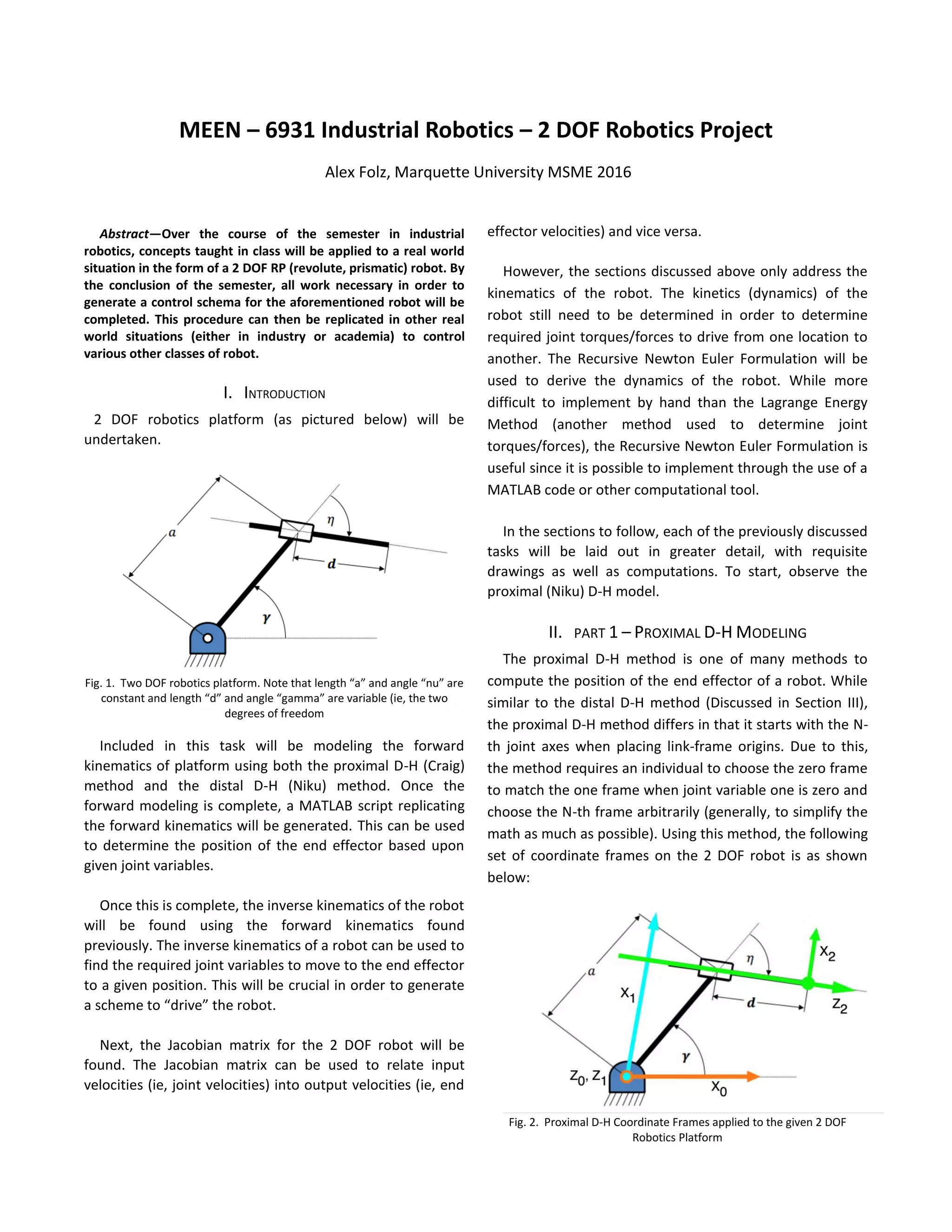

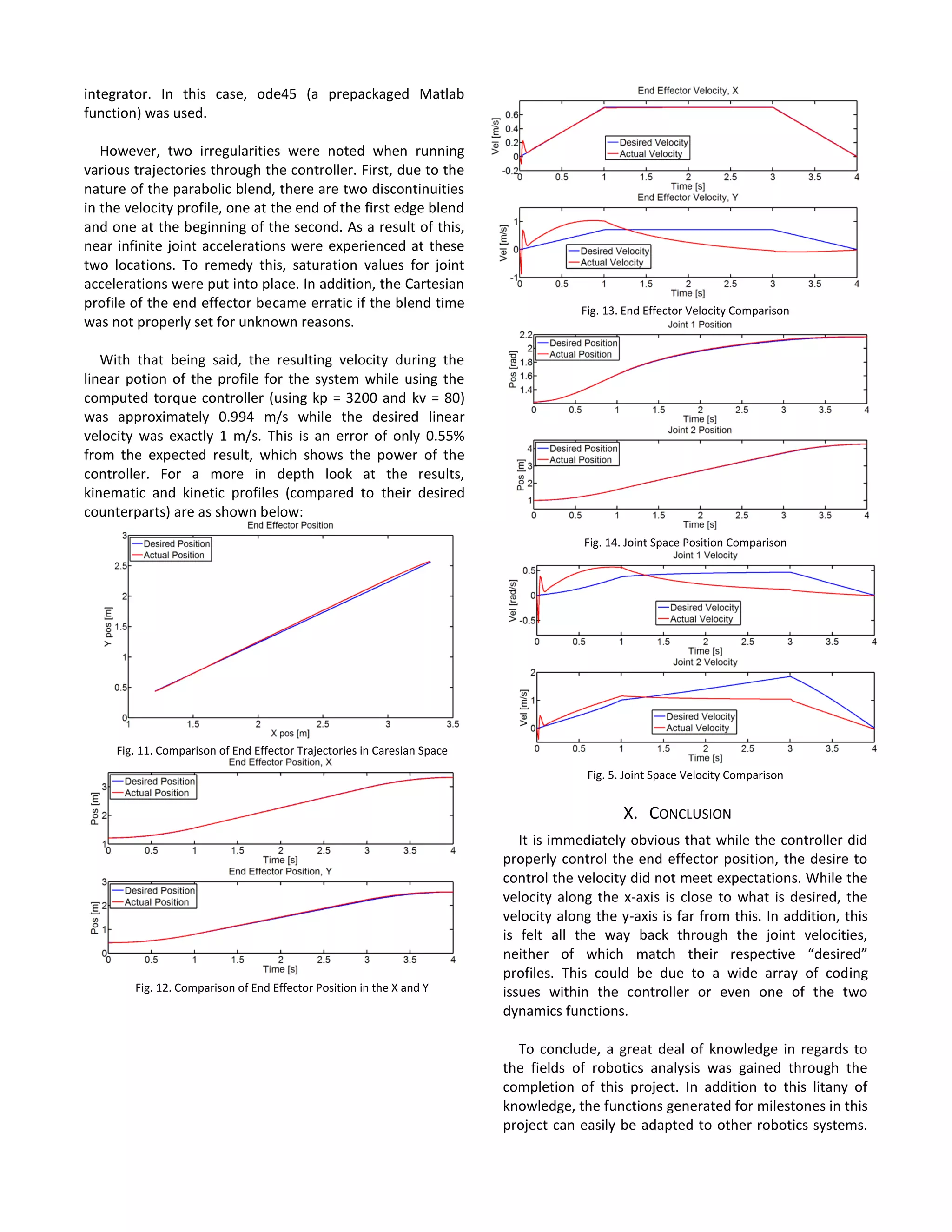

![To test the trajectory-planning algorithm generated, a

move with characteristics shown on the following page was

input to the system:

Table 3: Desired Trajectory Characteristics

Placing the above values into the algorithm generated

yielded the following kinematic profiles:

Fig. 5. Desired End Effector Position in Cartesian Space

Fig. 6 Desired End Effector in X and Y as a function of time

Fig. 7 Desired End Effector Velocity as a function of time

Fig. 8 Desired Joint Space Velocities to Acquire Desired Cartesian Space

Velocities

Fig. 9 Desired Joint Torques and Forces to Achieve Desired Trajectory

However, the Torques and Forces calculated and plotted

in Fig. 9 represent those that were using the inverse

dynamics function. To successfully control the robot, it will

be desired to use the forward dynamics function. This leads

to the last section of this report: Robot Control.

IX. PART 8 – ROBOT CONTROL

In order to control the 2 DOF robot being investigated, a

computed torque controller will be used, the block diagram

for which is shown below:

Fig. 10 Computed Torque Controller Block Diagram

In the layout as shown, q, q_dot and q_ddot can be

treated as the joint space outputs of the inverse dynamics,

as shown in the trajectory planning section of this report.

Inverse Dynamics will remain unchanged from the program

written previously and “Robot” will be the forward

dynamics model of the robot run though a numerical

Parameters Value

Velocity [m/s] 1

Angle Nu [deg] 45

Final Time [s] 4

Blend Time [s] 1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ac953a11-bf44-4012-a03d-e0de85935020-160408015616/75/Robotics_Final_Paper_Folza-7-2048.jpg)

![While minor changes would be necessary, it can even be

adapted for an RR bot or a PP bot.

Future work in terms of the project is two fold. First,

the error that caused the errors seen in joint velocities as

well as the y-axis velocity in the control system should be

found and remedied. Once this is complete and

functioning properly, an interesting side project would be

to build a scale model replica of the robot dissected for

the project to experimentally determine whether or not

the modeling completed was correct.

APPENDIX

A. Matlab Code

%Test Loop

%Alex Folz

%Industrial robotics

%Project

%2 DOF RP Bot

%#ok<*SAGROW>

%Code for testing 2 DOF Bot

clc

clear

global a eta M1 M2 L1 L2 I1 I2 g

% define constants

deg2rad = pi/180;

a = 1;

eta = 100*deg2rad;

M1 = 10;

M2 = 5;

L1 = 0.5;

L2 = 0.25;

I1 = 0.8;

I2 = 0.2;

g = -9.81;

g_amma(1) = 2;

d(1) = 1;

g_amma_dot = 0.01;

d_dot = 0.0;

i = 1;

t = 0;

ts = 0.01;

time_period = ts;

time_total = 5;

final = time_total/ts;

g_amma_dot(1) = 1;

d_dot(1) = 0.5;

g_amma_ddot(1) = 0;

d_ddot(1) = 0;

while i <= final

%g_amma_dot = 1+i/1000;

%d_dot = 1+i/1000;

[x(i), y(i)] = forward_kinematics(g_amma(i), d(i));

[g_amma(i), d(i)]=inverse_kinematics(x(i),y(i));

[x_dot(i), y_dot(i)] = jacobian(g_amma_dot, d_dot, g_amma(i), d(i));

[g_amma_dot(i) , d_dot(i)] = inverse_jacobian(x_dot(i), y_dot(i),

g_amma(i) ,d(i));

if i >= 2

g_amma_ddot(i) = (g_amma_dot(i)-g_amma_dot(i-1))/ts;

d_ddot(i) = (d_dot(i)-d_dot(i-1))/ts;

end

theta(:,:,i) = [g_amma(i); d(i)];

theta_dot(:,:,i) = [g_amma_dot(i); d(i)];

theta_ddot(:,:,i) = [g_amma_ddot(i); d_ddot(i)];

[tau(:,:,i)] = inverse_dynamics(theta(:,:,i), theta_dot(:,:,i),

theta_ddot(:,:,i));

Tau1(i) = tau(1,1,i);

F2(i) = tau(1,2,i);

if i < final

g_amma(i+1) = g_amma(i)+g_amma_dot(i)*ts;

d(i+1) = d(i)+d_dot(i)*ts;

end

time(i) = t;

i = i + 1;

t = t + ts;

end

figure(1)

plot(x,y)

title('End Effector Position')

ylabel('X [m]')

xlabel('Y [m]')

figure(2)

subplot(2,1,1)

plot(time,g_amma)

title('Joint 1 Position')

ylabel('Gamma [rad]')

xlabel('Time [s]')

subplot(2,1,2)

plot(time,d)

title('Joint 2 Position')

ylabel('d [m]')

xlabel('Time [s]')

figure(3)

subplot(2,1,1)

plot(time,x_dot)

title('End Effector Velocity, X')

ylabel('X dot [m/s]')

xlabel('Time [s]')

subplot(2,1,2)

plot(time,y_dot)

title('End Effector Velocity, Y')

ylabel('Y dot [m/s]')

xlabel('Time [s]')

figure(4)

subplot(2,1,1)

plot(time,g_amma_dot)

title('Joint 1 Velocity')

ylabel('Gamma dot [rad/s]')

xlabel('Time [s]')

subplot(2,1,2)

plot(time,d_dot)

title('Joint 2 Velocity')](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ac953a11-bf44-4012-a03d-e0de85935020-160408015616/75/Robotics_Final_Paper_Folza-9-2048.jpg)

![ylabel('d dot [m/s]')

xlabel('Time [s]')

figure(5)

subplot(2,1,1)

plot(time,Tau1)

title('Joint 1 Torque')

ylabel('Torque [Nm]')

xlabel('Time [s]')

subplot(2,1,2)

plot(time,F2)

title('Joint 2 Force')

ylabel('Force [N]')

xlabel('Time [s]')

function [x , y] = forward_kinematics(g_amma, d)

%Forward Kinematics

global a eta

a1 = a*cos(eta);

a2 = a*sin(eta);

beta = eta-g_amma;

T_tot(:,:) = [sin(beta) 0 cos(beta) sin(beta)*a2+cos(beta)*(d+a1); cos(beta)

0 -sin(beta) cos(beta)*a2-sin(beta)*(d+a1); 0 1 0 0; 0 0 0 1];

Pos(:,:) = (T_tot)*[0; 0; 0; 1];

x = Pos(1);

y = Pos(2);

end

function [g_amma, d]=inverse_kinematics(x,y)

%Inverse Kinematics

global a eta

a1 = a*cos(eta);

a2 = a*sin(eta);

g_amma = eta-2*atan2((x-sqrt(-(a2^2)+(x^2)+(y^2))),a2+y);

beta = eta-g_amma;

d = (x-a2*sin(beta)-a1*cos(beta))/cos(beta);

end

function [x_dot y_dot] = jacobian(g_amma_dot, d_dot, g_amma, d)

%Jacobian

global a eta

a1 = a*cos(eta);

a2 = a*sin(eta);

beta = eta-g_amma;

Vel(:,:) = [ sin(beta)*(a1 + d) - a2*cos(beta), cos(beta); cos(beta)*(a1 + d) +

a2*sin(beta), sin(beta)]*[g_amma_dot; d_dot];

x_dot = Vel(1);

y_dot = Vel(2);

end

function[g_amma_dot , d_dot] = inverse_jacobian(x_dot, y_dot, g_amma

,d)

%Inverse Jacobian

global a eta

a1 = a*cos(eta);

a2 = a*sin(eta);

beta = eta-g_amma;

Vel(:,:) = [ sin(beta)*(a1 + d) - a2*cos(beta), cos(beta); cos(beta)*(a1 + d) +

a2*sin(beta), sin(beta)]^(-1)*[x_dot; y_dot];

g_amma_dot = Vel(1);

d_dot = Vel(2);

end

function [theta_new , theta_dot_new] = forward_dynamics(theta,

theta_dot, tau, time_period)

%Forward Dynamics

% INPUTS: theta (current position of the robot), theta_dot (current

velocities), tau (current

%generalized forces, time_period (time period for simulation)

% OUTPUTS: theta_new (predicted position)

% theta_dot_new (predicted velocities)

%Establish Global Variables

global a eta M1 M2 L1 L2 I1 I2 g

a1 = a*cos(eta);

a2 = a*sin(eta);

theta_new = zeros(2,1); %initialize column vector

theta_dot_new = zeros(2,1);

%From the state model definition, p(2) & p(4) are the derivatives of

%p(1) & p(3), respectively

theta_new(1) = theta_dot(1);

theta_new(2) = theta_dot(2);

%Calculate components of the Mass matrix

m1 = M1*(0.25*a^2)+M2*(L2^2-

2*L2*(a+theta(2))+a^2+2*a1*theta(2)+theta(2)^2)+I1+I2;

m2 = -M2*a2;

m3 = -M2*a2;

m4 = M2;

%Caculate components of the Force vector

v1 = 2*M2*(a1+theta(2)-L2)*theta_dot(1)*theta_dot(2);

v2 = -M2*(a1+theta(2)-L2)*theta_dot(1)^2;

g1 = (M1*L1*cos(-theta(1))+M1*a*(sin(eta-theta(1))*(sin(eta)-

sin(theta(1))))+M2*cos(eta-theta(1))*(a1-theta(2)+L2)+M2*a2*sin(eta-

theta(1)))*g;

g2 = M2*g*sin(theta(1)-eta);

%Initialize Mass Matrix and Force vector

m = [m1 m2; m3 m4];

F = [v1+g1+tau(1); v2+g2+tau(2)];

%Using the Mass Matrix and Force vector, determine pdot(2) &pdot(4)

%which are the angular acceleration of theta and alpha, respectively

acc= m^(-1)*F;

theta_dot_new(1) = acc(1,1);

theta_dot_new(2) = acc(2,1);

End](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ac953a11-bf44-4012-a03d-e0de85935020-160408015616/75/Robotics_Final_Paper_Folza-10-2048.jpg)

![function tau = inverse_dynamics(theta, theta_dot, theta_ddot)

%Inverse Dynamics

%Establish Global Variables

global a eta M1 M2 L1 L2 I1 I2 g

a1 = a*cos(eta);

a2 = a*sin(eta);

%Calculate components of the Mass matrix

m1 = M1*(0.25*a^2)+M2*(L2^2-

2*L2*(a+theta(2))+a^2+2*a1*theta(2)+theta(2)^2)+I1+I2;

m2 = -M2*a2;

m3 = -M2*a2;

m4 = M2;

%Caculate components of the Force vector

v1 = 2*M2*(a1+theta(2)-L2)*theta_dot(1)*theta_dot(2);

v2 = -M2*(a1+theta(2)-L2)*theta_dot(1)^2;

g1 = (M1*L1*cos(-theta(1))+M1*a*(sin(eta-theta(1))*(sin(eta)-

sin(theta(1))))+M2*cos(eta-theta(1))*(a1-theta(2)+L2)+M2*a2*sin(eta-

theta(1)))*g;

g2 = M2*g*sin(theta(1)-eta);

%Initialize Mass Matrix and Force vector

m = [m1 m2; m3 m4];

F = [v1+g1; v2+g2];

T= m(:,:)*theta_ddot(:,:)+F;

tau(1) = T(1,1);

tau(2) = T(2,1);

end

%Alex Folz

%Meen-6931, Industrial Robotics

%Recursive Newton Euler Solver

%2 DOF RP Bot

clc

clear

syms a a1 a2 L1 L2 d dd ddd eta gam g gd gdd m1 m2 I11 I22

z = [0;0;1];

w0 = [0;0;0];

al0 = [0;0;0];

v0 = [0;0;0];

a0 = [0;0;0];

I1 = [I11*(cos(eta))^2 0 0; 0 I11 0;0 0 I11*(cos(eta))^2];

I2 = [I22 0 0; 0 I22 0; 0 0 0];

r1 = [a2; 0; 0];

r2 = [0; 0; d+a1];

rc1 = [(L1-a)*sin(eta); 0; L1*cos(eta)];

rc2 = [0; 0; -L2];

R01 = [sin(eta-gam) 0 cos(eta-gam); cos(eta-gam) 0 -sin(eta-gam); 0 1 0];

R12 = [1 0 0; 0 1 0; 0 0 1];

R10 = [sin(eta-gam) cos(eta-gam) 0; 0 0 1; cos(eta-gam) -sin(eta-gam) 0];

R21 = [1 0 0; 0 1 0; 0 0 1];

g0 = [0;g;0];

r.w1 = R10*(w0+z*gd);

r.w2 = r.w1;

r.al1 = R10*(al0+z*gdd+cross(w0,(z*gd)));

r.al2 = r.al1;

r.v1 = R10*v0+cross(r.w1,r1);

r.v2 = R21*(r.v1+z*dd)+cross(r.w2,r2);

r.a1 = R10*a0+cross(r.al1,r1)+cross(r.w1,cross(r.w1,r1));

r.a2 =

(R21*r.a1+z*ddd)+cross(r.al2,r2)+cross(r.w2,cross(r.w2,r2))+2*cross(r.w2,(

R21*z*dd));

r.ac1 = r.a1+cross(r.al1,rc1)+cross(r.w1,cross(r.w1,rc1));

r.ac2 = r.a2+cross(r.al2,rc2)+cross(r.w2,cross(r.w2,rc2));

r.g1 = R10*g0;

r.g2 = R21*r.g1;

r.f221 = [0;0;0]+m2*r.g2+m2*r.ac2;

r.f121 = R12*r.f221;

r.f110=r.f121+m1*r.g1+m1*r.ac1;

r.n221=[0;0;0]+cross((r2+rc2),r.f221)-

cross(rc2,[0;0;0])+I2*r.al2+cross(r.w2,(I2*r.w2));

r.n121=R12*r.n221;

r.n110=r.n121+cross((r1+rc1),r.f110)-

cross(rc1,r.f121)+I1*r.al1+cross(r.w1,(I1*r.w1));

r.n010=R01*r.n110;

r.T1 = transpose(r.n010)*z;

r.T2 = transpose(r.f121)*z;

r.m1 = collect(r.T1,gdd);

r.n1 = collect(r.m1,ddd);

r.o1 = collect(r.n1,gd^2);

r.p1 = collect(r.o1, dd*gd);

r.T1f = r.p1;

%Trajectory Planning

%Alex Folz

%Meen-6931, Industrial Robotics

%Final Project

clc

clear

global a eta M1 M2 L1 L2 I1 I2 g

% define constants

deg2rad = pi()/180;

a = 1;

eta = 100*deg2rad;

M1 = 10;

M2 = 5;

L1 = 0.5;

L2 = 0.25;

I1 = 0.8;

I2 = 0.2;

g = -9.81;

deg2rad = pi/180;

v_dot = 1;

nu = 45*deg2rad;

tf = 4;](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ac953a11-bf44-4012-a03d-e0de85935020-160408015616/75/Robotics_Final_Paper_Folza-11-2048.jpg)

![tb = 1;

g_amma_des(1) = 70*deg2rad;

d_des(1) = 1;

g_amma_act(1) = 70*deg2rad;

d_act(1) = 1;

i = 1;

x_dot_lin = v_dot*sin(nu);

y_dot_lin = x_dot_lin*tan(nu);

ts = 0.01;

final = tf/ts;

ib = tb/ts;

ifb = (tf-tb)/ts;

[x_des,y_des] = forward_kinematics(g_amma_des(i), d_des(i));

x_des(1) = x_des;

y_des(1) = y_des;

xf = x_des(1) + x_dot_lin*(tf-tb);

yf = y_des(1) + y_dot_lin*(tf-tb);

for i = 2:1:final

if i <= ib

x_des(i) = x_des(1)+0.5*x_dot_lin/(tb)*(ts*i)^2;

y_des(i) = y_des(1)+0.5*y_dot_lin/(tb)*(ts*i)^2;

[g_amma_des(i), d_des(i)]=inverse_kinematics(x_des(i),y_des(i));

x_dot_des(i) = (x_des(i)-x_des(i-1))/ts;

y_dot_des(i) = (y_des(i)-y_des(i-1))/ts;

elseif i >= ifb

x_des(i) = xf-0.5*x_dot_lin/(tb)*(tf-ts*i)^2;

y_des(i) = yf-0.5*y_dot_lin/(tb)*(tf-ts*i)^2;

[g_amma_des(i), d_des(i)]=inverse_kinematics(x_des(i),y_des(i));

x_dot_des(i) = (x_des(i)-x_des(i-1))/ts;

y_dot_des(i) = (y_des(i)-y_des(i-1))/ts;

else

x_des(i) = x_des(1)+0.5*x_dot_lin+x_dot_lin*(ts*i-tb);

y_des(i) = y_des(1)+0.5*y_dot_lin+y_dot_lin*(ts*i-tb);

[g_amma_des(i), d_des(i)]=inverse_kinematics(x_des(i),y_des(i));

x_dot_des(i) = (x_des(i)-x_des(i-1))/ts;

y_dot_des(i) = (y_des(i)-y_des(i-1))/ts;

end

time(i) = ts*i;

[g_amma_dot_des(i) , d_dot_des(i)] = inverse_jacobian(x_dot_des(i),

y_dot_des(i), g_amma_des(i) ,d_des(i));

g_amma_ddot_des(i) = (g_amma_dot_des(i)-g_amma_dot_des(i-1))/ts;

d_ddot_Des(i) = (d_dot_des(i)-d_dot_des(i-1))/ts;

theta_des(:,:,i) = [g_amma_des(i); d_des(i)];

theta_dot_des(:,:,i) = [g_amma_dot_des(i); d_des(i)];

theta_ddot_des(:,:,i) = [g_amma_ddot_des(i); d_ddot_Des(i)];

[tau_des(:,:,i)] = inverse_dynamics(theta_des(:,:,i), theta_dot_des(:,:,i),

theta_ddot_des(:,:,i));

Tau1_des(i) = tau_des(1,1,i);

F2_des(i) = tau_des(1,2,i);

end

figure(1)

subplot(2,1,1)

plot(time,x_dot_des)

title('End Effector Velocity, X')

ylabel('X dot [m/s]')

xlabel('Time [s]')

subplot(2,1,2)

plot(time,y_dot_des)

title('End Effector Velocity, Y')

ylabel('Y dot [m/s]')

xlabel('Time [s]')

figure(2)

subplot(2,1,1)

plot(time,g_amma_dot_des)

title('Joint 1 Velocity')

ylabel('Gamma dot [rad/s]')

xlabel('Time [s]')

subplot(2,1,2)

plot(time,d_dot_des)

title('Joint 2 Velocity')

ylabel('d dot [m/s]')

xlabel('Time [s]')

figure(3)

subplot(2,1,1)

plot(time,x_des)

title('End Effector X')

ylabel('X Pos [m]')

xlabel('Time [s]')

subplot(2,1,2)

plot(time,y_des)

title('End Effector Y')

ylabel('Y Pos [m]')

xlabel('Time [s]')

figure(4)

plot(x_des,y_des)

title('End Effector Position')

ylabel('Y [m]')

xlabel('X [m]')

figure(5)

subplot(2,1,1)

plot(time,Tau1_des)

title('Joint 1 Torque')

ylabel('Torque [Nm]')

xlabel('Time [s]')

subplot(2,1,2)

plot(time,F2_des)

title('Joint 2 Force')

ylabel('Force [N]')

xlabel('Time [s]')

%Alex Folz

%Meen-6931](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ac953a11-bf44-4012-a03d-e0de85935020-160408015616/75/Robotics_Final_Paper_Folza-12-2048.jpg)

![%Robot Control

%#ok<*SAGROW>

clc

clear

global a eta M1 M2 L1 L2 I1 I2 g

% define constants

deg2rad = pi()/180;

a = 1;

eta = 100*deg2rad;

M1 = 10;

M2 = 5;

L1 = 0.5;

L2 = 0.25;

I1 = 0.8;

I2 = 0.2;

g = -9.81;

deg2rad = pi/180;

v_dot = 1;

nu = 45*deg2rad;

tf = 4;

tb = 1;

g_amma_des(1) = 70*deg2rad;

d_des(1) = 1;

i = 1;

x_dot_lin = v_dot*sin(nu);

y_dot_lin = x_dot_lin*tan(nu);

ts = 0.01;

time_period = ts;

final = tf/ts;

ib = tb/ts;

ifb = (tf-tb)/ts;

[x_des, y_des] = forward_kinematics(g_amma_des(i), d_des(i));

x_des(1) = x_des;

y_des(1) = y_des;

xf = x_des(1) + x_dot_lin*(tf-tb);

yf = y_des(1) + y_dot_lin*(tf-tb);

%Complete Inverse kinematics and jacobian to find q, q_dot, & q_ddot

for i = 2:1:final

if i <= ib

x_des(i) = x_des(1)+0.5*x_dot_lin/(tb)*(ts*i)^2;

y_des(i) = y_des(1)+0.5*y_dot_lin/(tb)*(ts*i)^2;

[g_amma_des(i), d_des(i)]=inverse_kinematics(x_des(i),y_des(i));

x_dot_des(i) = (x_des(i)-x_des(i-1))/ts;

y_dot_des(i) = (y_des(i)-y_des(i-1))/ts;

elseif i >= ifb

x_des(i) = xf-0.5*x_dot_lin/(tb)*(tf-ts*i)^2;

y_des(i) = yf-0.5*y_dot_lin/(tb)*(tf-ts*i)^2;

[g_amma_des(i), d_des(i)]=inverse_kinematics(x_des(i),y_des(i));

x_dot_des(i) = (x_des(i)-x_des(i-1))/ts;

y_dot_des(i) = (y_des(i)-y_des(i-1))/ts;

else

x_des(i) = x_des(1)+0.5*x_dot_lin+x_dot_lin*(ts*i-tb);

y_des(i) = y_des(1)+0.5*y_dot_lin+y_dot_lin*(ts*i-tb);

[g_amma_des(i), d_des(i)]=inverse_kinematics(x_des(i),y_des(i));

x_dot_des(i) = (x_des(i)-x_des(i-1))/ts;

y_dot_des(i) = (y_des(i)-y_des(i-1))/ts;

end

time(i) = ts*i;

[g_amma_dot_des(i) , d_dot_des(i)] = inverse_jacobian(x_dot_des(i),

y_dot_des(i), g_amma_des(i) ,d_des(i));

g_amma_ddot_des(i) = (g_amma_dot_des(i)-g_amma_dot_des(i-1))/ts;

d_ddot_des(i) = (d_dot_des(i)-d_dot_des(i-1))/ts;

if g_amma_ddot_des(i) >= 1

g_amma_ddot_des(i) = 1;

end

if g_amma_ddot_des(i) <= -1

g_amma_ddot_des(i) = -1;

end

if d_ddot_des(i) >= 3

d_ddot_des(i) = 3;

end

if d_ddot_des(i) <= -3

d_ddot_des(i) = -3;

end

theta_des(:,:,i) = [g_amma_des(i); d_des(i)];

theta_dot_des(:,:,i) = [g_amma_dot_des(i); d_des(i)];

theta_ddot_des(:,:,i) = [g_amma_ddot_des(i); d_ddot_des(i)];

end

g_amma_act(1) = 70*deg2rad;

d_act(1) = 1;

[x_act, y_act] = forward_kinematics(g_amma_act(1), d_act(1));

x_act(1) = x_act;

y_act(1) = y_act;

x_dot_act(1) = 0;

y_dot_act(1) = 0;

[g_amma_dot_act(1) , d_dot_act(1)] = inverse_jacobian(x_dot_act(1),

y_dot_act(1), g_amma_act(1) ,d_act(1));

i = 1;

kp = 3200;

kv = 80;

%feed in results to inverse dynamics to get tau

for i = 1:1:final

theta_actual(:,:,i) = [g_amma_act(i); d_act(i)];

theta_dot_actual(:,:,i) = [g_amma_dot_act(i); d_dot_act(i)];

g_amma_control(i) = g_amma_des(i)-g_amma_act(i);

g_amma_dot_control(i) = g_amma_dot_des(i) - g_amma_dot_act(i);](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ac953a11-bf44-4012-a03d-e0de85935020-160408015616/75/Robotics_Final_Paper_Folza-13-2048.jpg)

![d_control(i) = d_des(i) - d_act(i);

d_dot_control(i) = d_dot_des(i) - d_dot_act(i);

theta_control(:,:,i) = [g_amma_control(i); d_control(i)];

theta_dot_control(:,:,i) = [g_amma_dot_control(i); d_dot_control(i)];

theta_ddot_control(:,:,i) =

theta_control(:,:,i)*kp+theta_dot_control(:,:,i)*kv+theta_ddot_des(:,:,i);

[tau_control(:,:,i)] = inverse_dynamics(theta_des(:,:,i),

theta_dot_des(:,:,i), theta_ddot_control(:,:,i));

ic = [theta_actual(1,1,i) theta_dot_actual(1,1,i) theta_actual(2,1,i)

theta_dot_actual(2,1,i) tau_control(1,1,i) tau_control(1,2,i)];

%ic = [theta_actual(1,1,1) theta_dot_actual(1,1,1) theta_actual(2,1,1)

theta_dot_actual(2,1,1) tau_control(1,1,i) tau_control(1,2,i)];

[tout, qout] = ode45('forward_dynamics_control',time_period,ic);

g_amma_act(i+1) = qout(end,1);

g_amma_dot_act(i+1) = qout(end,2);

d_act(i+1) = qout(end,3);

d_dot_act(i+1) = qout(end,4);

[x_act(i+1), y_act(i+1)] = forward_kinematics(g_amma_act(i+1),

d_act(i+1));

[x_dot_act(i+1), y_dot_act(i+1)] = jacobian(g_amma_dot_act(i+1),

d_dot_act(i+1), g_amma_act(i+1), d_act(i+1));

end

figure(1)

plot(x_des,y_des,'blue')

hold

plot(x_act,y_act, 'red')

title('End Effector Position')

ylabel('Y pos [m]')

xlabel('X pos [m]')

legend('Desired Position','Actual Position','location', 'northwest')

figure(2)

subplot(2,1,1)

plot(time,x_dot_des,'blue')

hold

plot(time,x_dot_act(1:400),'red')

title('End Effector Velocity, X')

ylabel('Vel [m/s]')

xlabel('Time [s]')

legend('Desired Velocity','Actual Velocity','location', 'northwest')

subplot(2,1,2)

plot(time,y_dot_des,'blue')

hold

plot(time,y_dot_act(1:400),'red')

title('End Effector Velocity, Y')

ylabel('Vel [m/s]')

xlabel('Time [s]')

legend('Desired Velocity','Actual Velocity','location', 'northwest')

figure(3)

subplot(2,1,1)

plot(time,g_amma_dot_des,'blue')

hold

plot(time,g_amma_dot_act(1:400),'red')

title('Joint 1 Velocity')

ylabel('Vel [rad/s]')

xlabel('Time [s]')

legend('Desired Velocity','Actual Velocity','location', 'northwest')

subplot(2,1,2)

plot(time,d_dot_des,'blue')

hold

plot(time,d_dot_act(1:400),'red')

title('Joint 2 Velocity')

ylabel('Vel [m/s]')

xlabel('Time [s]')

legend('Desired Velocity','Actual Velocity','location', 'northwest')

figure(4)

subplot(2,1,1)

plot(time,x_des,'blue')

hold

plot(time,x_act(1:400),'red')

title('End Effector Position, X')

ylabel('Pos [m]')

xlabel('Time [s]')

legend('Desired Position','Actual Position','location', 'northwest')

subplot(2,1,2)

plot(time,y_des,'blue')

hold

plot(time,y_act(1:400),'red')

title('End Effector Position, Y')

ylabel('Pos [m]')

xlabel('Time [s]')

legend('Desired Position','Actual Position','location', 'northwest')

figure(5)

subplot(2,1,1)

plot(time,g_amma_des,'blue')

hold

plot(time,g_amma_act(1:400),'red')

title('Joint 1 Position')

ylabel('Pos [rad]')

xlabel('Time [s]')

legend('Desired Position','Actual Position','location', 'northwest')

subplot(2,1,2)

plot(time,d_des,'blue')

hold

plot(time,d_act(1:400),'red')

title('Joint 2 Position')

ylabel('Pos [m]')

xlabel('Time [s]')

legend('Desired Position','Actual Position','location', 'northwest')

function qnew = forward_dynamics_control(t,q)

%Forward Dynamics

% INPUTS: q (current position of the robot), q_dot (current velocities), tau

(current

%generalized forces, time_period (time period for simulation)

% OUTPUTS: q_new (predicted position)

% q_dot_new (predicted velocities)

%Establish Global Variables

global a eta M1 M2 L1 L2 I1 I2 g

a1 = a*cos(eta);

a2 = a*sin(eta);

qnew = zeros(4,1);

%From the state model definition, p(2) & p(4) are the derivatives of

%p(1) & p(3), respectively

qnew(1) = q(2);

qnew(3) = q(4);

tau(1) = q(5);

tau(2) = q(6);](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ac953a11-bf44-4012-a03d-e0de85935020-160408015616/75/Robotics_Final_Paper_Folza-14-2048.jpg)

![%Calculate components of the Mass matrix

m1 = M1*(0.25*a^2)+M2*(L2^2-

2*L2*(a+q(3))+a^2+2*a1*q(3)+q(3)^2)+I1+I2;

m2 = -M2*a2;

m3 = -M2*a2;

m4 = M2;

%Caculate components of the Force vector

v1 = 2*M2*(a1+q(3)-L2)*q(2)*q(4);

v2 = -M2*(a1+q(3)-L2)*q(2)^2;

g1 = (M1*L1*cos(-q(1))+M1*a*(sin(eta-q(1))*(sin(eta)-

sin(q(1))))+M2*cos(eta-q(1))*(a1-q(3)+L2)+M2*a2*sin(eta-q(1)))*g;

g2 = M2*g*sin(q(1)-eta);

%Initialize Mass Matrix and Force vector

m = [m1 m2; m3 m4];

F = [v1+g1+tau(1); v2+g2+tau(2)];

%Using the Mass Matrix and Force vector, determine pdot(2) &pdot(4)

%which are the angular acceleration of q and alpha, respectively

acc= m^(-1)*F;

qnew(2) = acc(1,1);

qnew(4) = acc(2,1);

qnew(5) = 0;

qnew(6) = 0;

end

B. Full Size Dynamics Matrices

𝑚(𝜃̈)

= [ 𝑚1 (

1

4

𝑎2

) + 𝑚2(𝐿2

2

− 2𝐿2(𝑎 + 𝑑) + 𝑎2

+ 2𝑎1 𝑑 + 𝑑2) + 𝐼1 + 𝐼2 −𝑚2 𝑎2

−𝑚2 𝑎2 𝑚2

]

(31)

𝑣(𝜃, 𝜃̇) = [

2𝑚2(𝑎1 + 𝑑 − 𝐿2)𝑑̇ 𝛾̇

−𝑚2(𝑎1 + 𝑑 + 𝐿2)𝛾̇2

] (32)

𝑔(𝜃)

= [

𝑚1 𝐿1 cos(−𝛾) + 𝑚1 𝑎(sin(𝜂 − 𝛾) (sin(𝜂) − sin(𝛾))) + 𝑚2 cos(𝜂 − 𝛾) (𝑎1 − 𝑑 + 𝐿2) + 𝑚2 𝑎2sin( 𝜂 − 𝛾)

𝑚2sin( 𝛾 − 𝜂)

]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ac953a11-bf44-4012-a03d-e0de85935020-160408015616/75/Robotics_Final_Paper_Folza-15-2048.jpg)