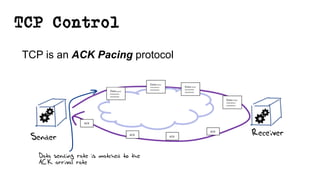

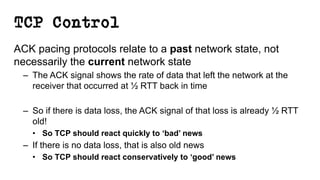

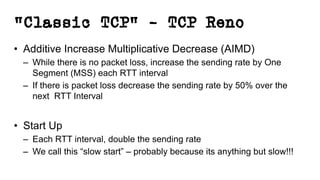

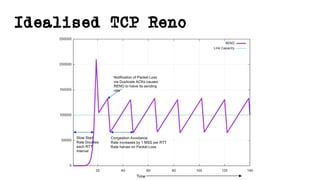

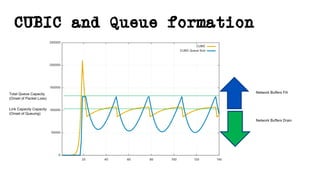

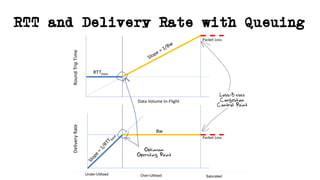

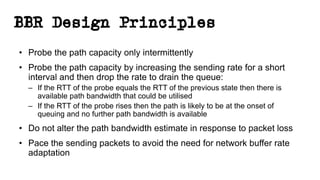

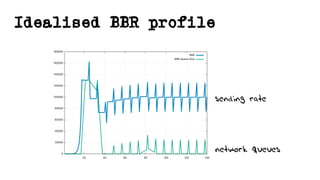

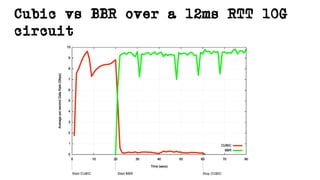

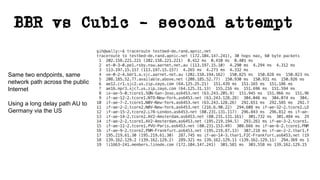

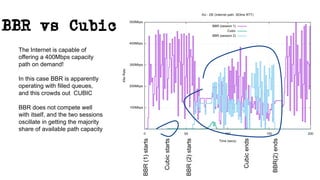

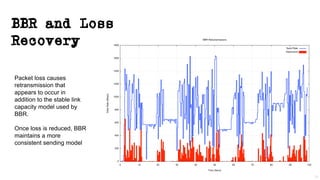

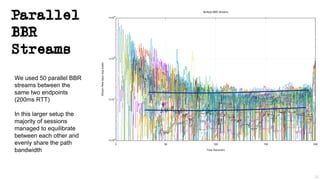

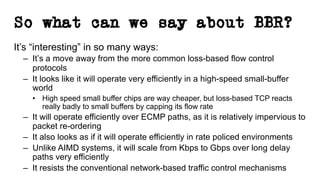

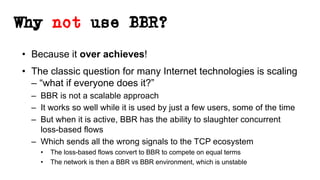

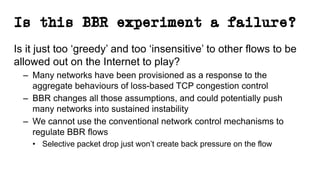

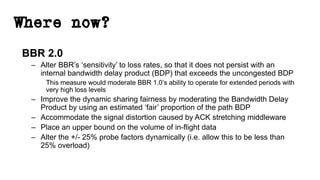

This document discusses TCP and a new flow control algorithm called BBR. It provides background on TCP and how its sending rate is controlled via ACK pacing. While TCP rates increased from kilobits to gigabits per second over time, it is not keeping up with optical transmission speeds approaching terabits. BBR aims to be more efficient than TCP by probing the network to detect the onset of queueing rather than relying on packet loss. Testing shows BBR can crowd out other flows and operate inefficiently against itself. While promising for high speeds, BBR may not scale well if widely adopted and requires further research to improve fairness against other flows.