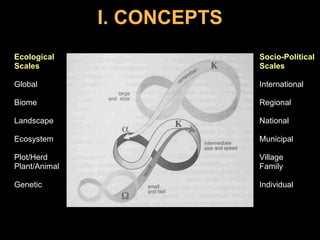

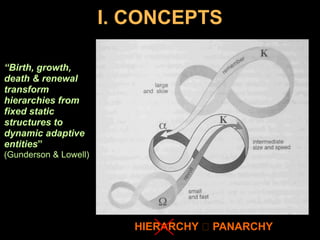

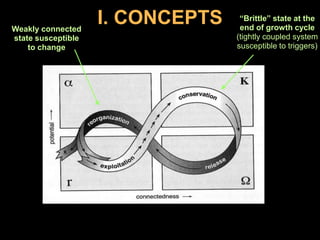

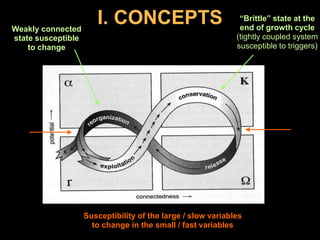

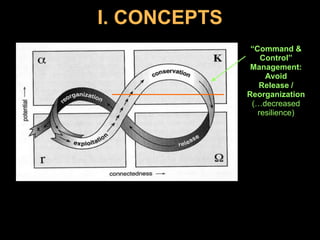

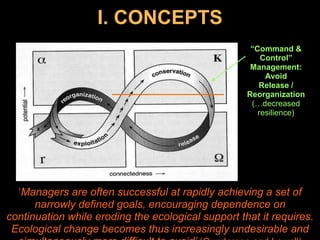

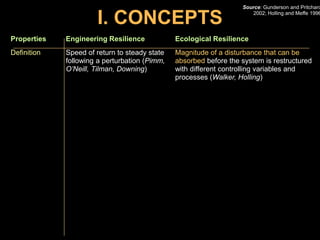

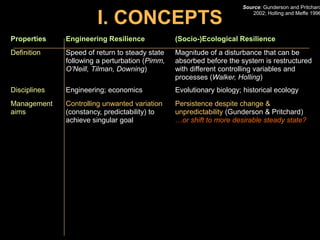

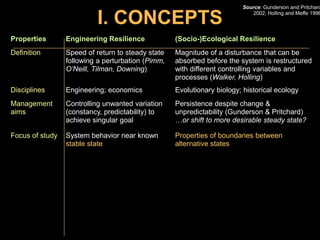

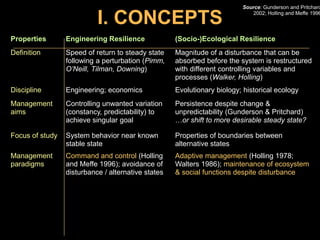

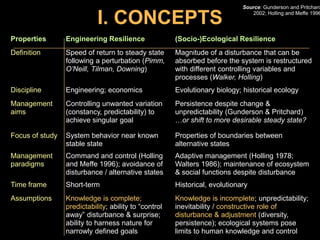

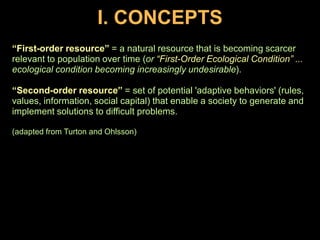

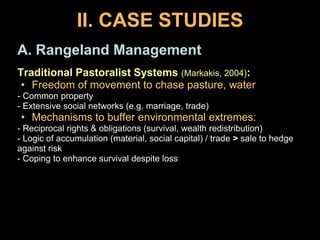

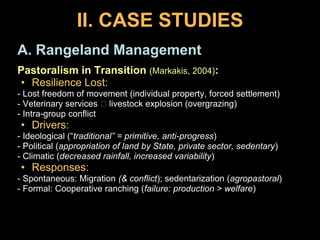

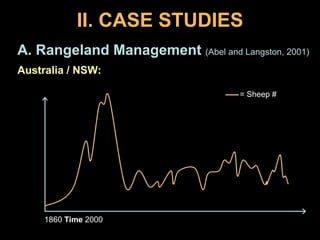

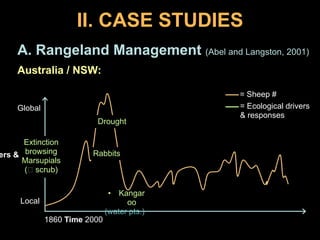

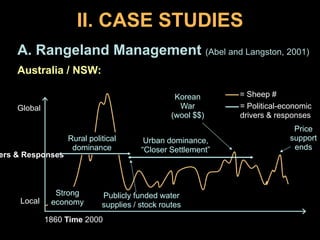

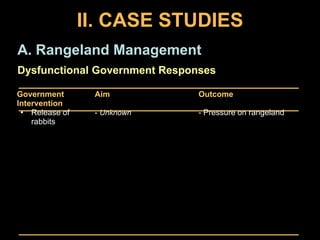

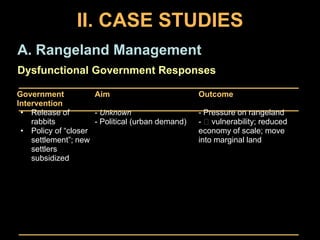

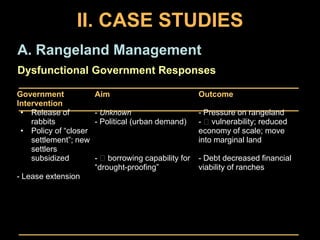

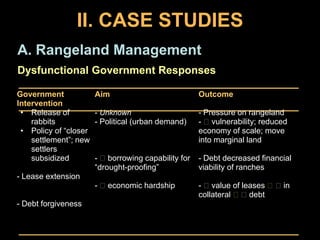

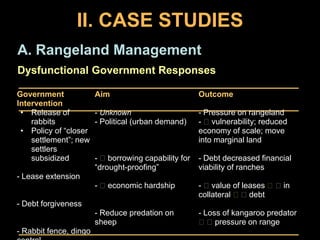

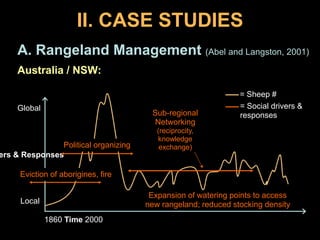

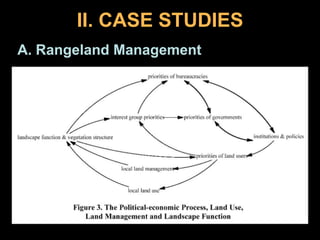

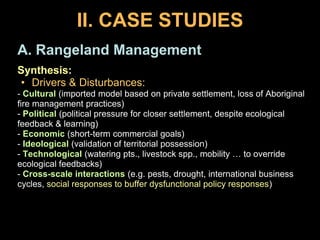

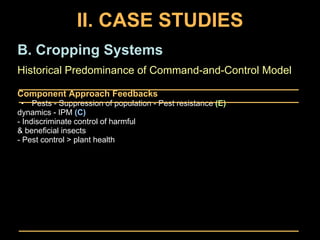

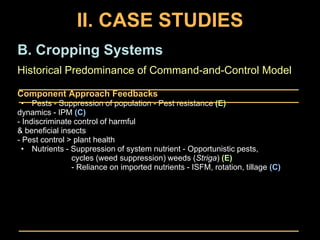

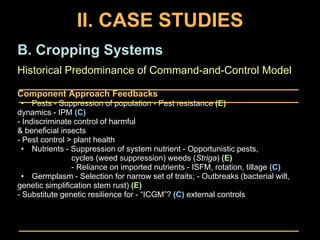

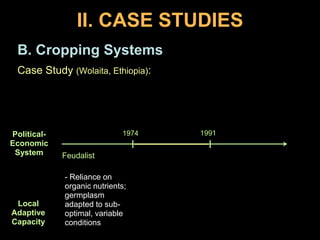

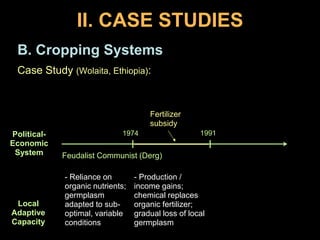

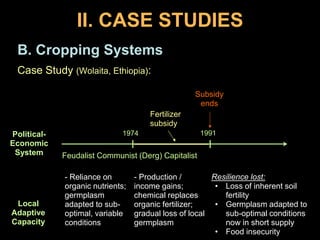

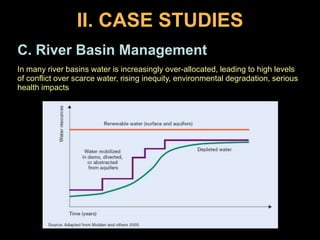

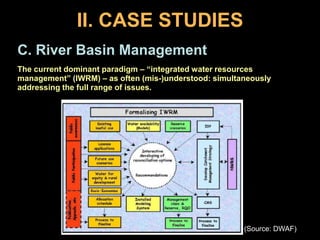

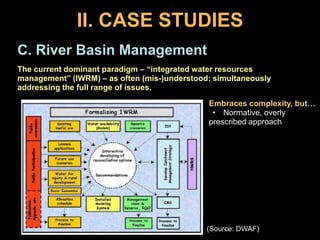

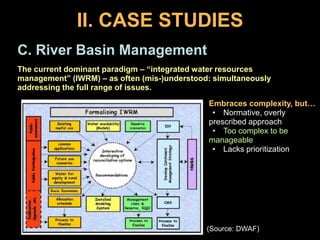

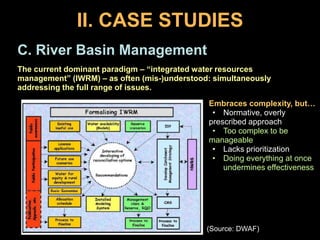

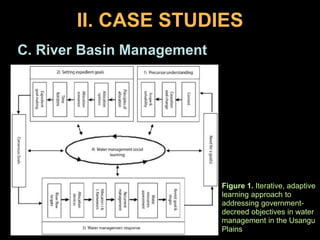

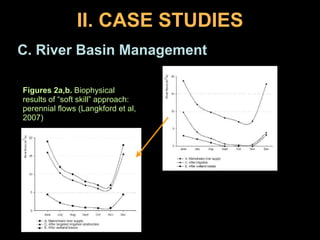

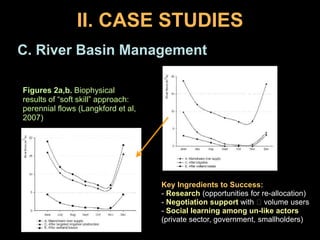

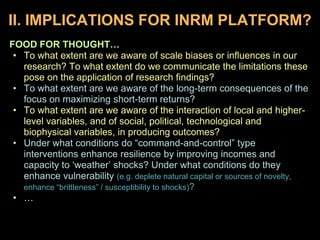

The document discusses the concepts of resilience and its implications in socio-ecological systems, particularly in the context of rangeland management. It contrasts 'engineering resilience' with 'ecological resilience,' highlighting the importance of adaptive management in the face of disturbances and change. Case studies illustrate the effects of various environmental and socio-political drivers on pastoral systems and their resilience strategies.