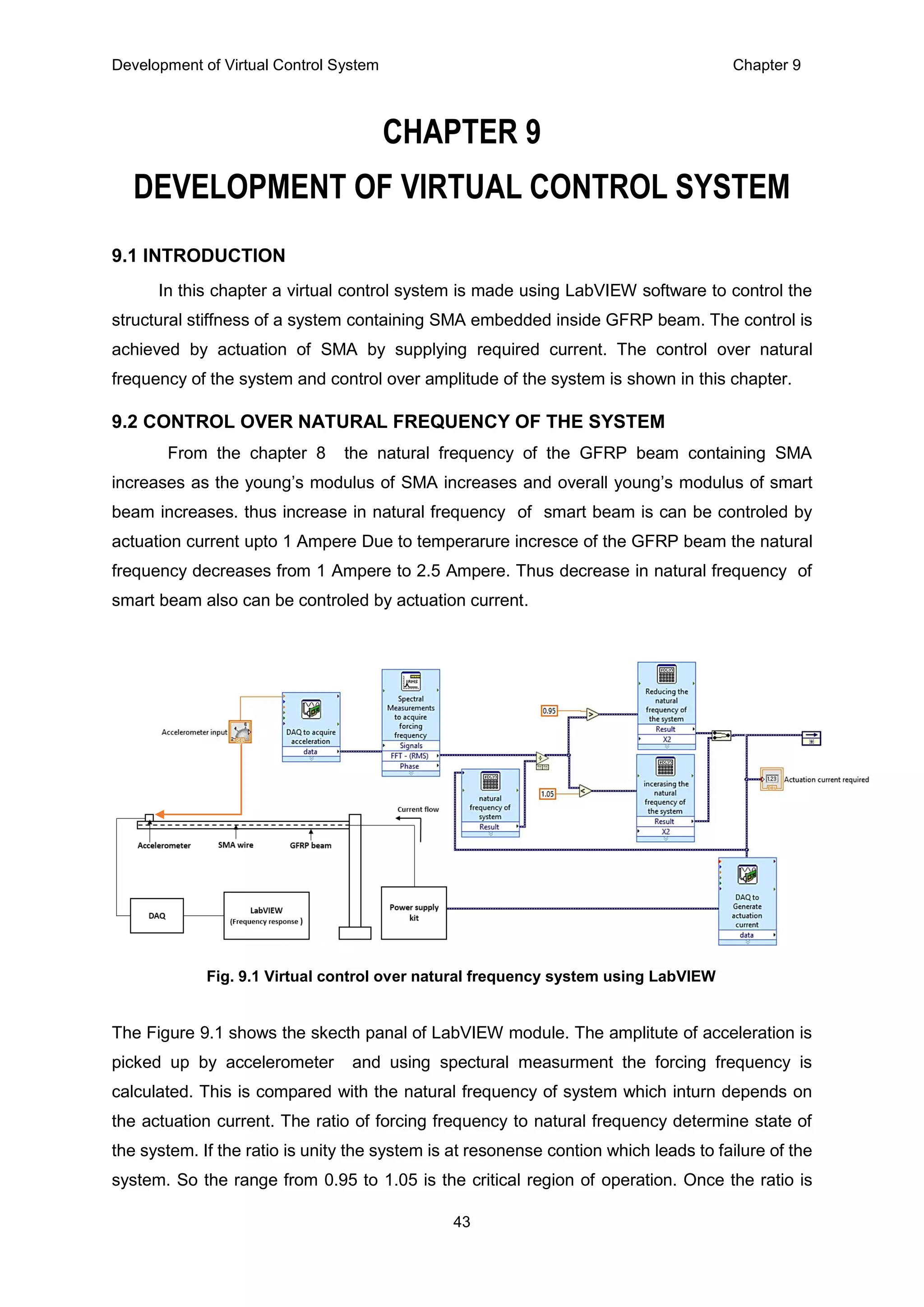

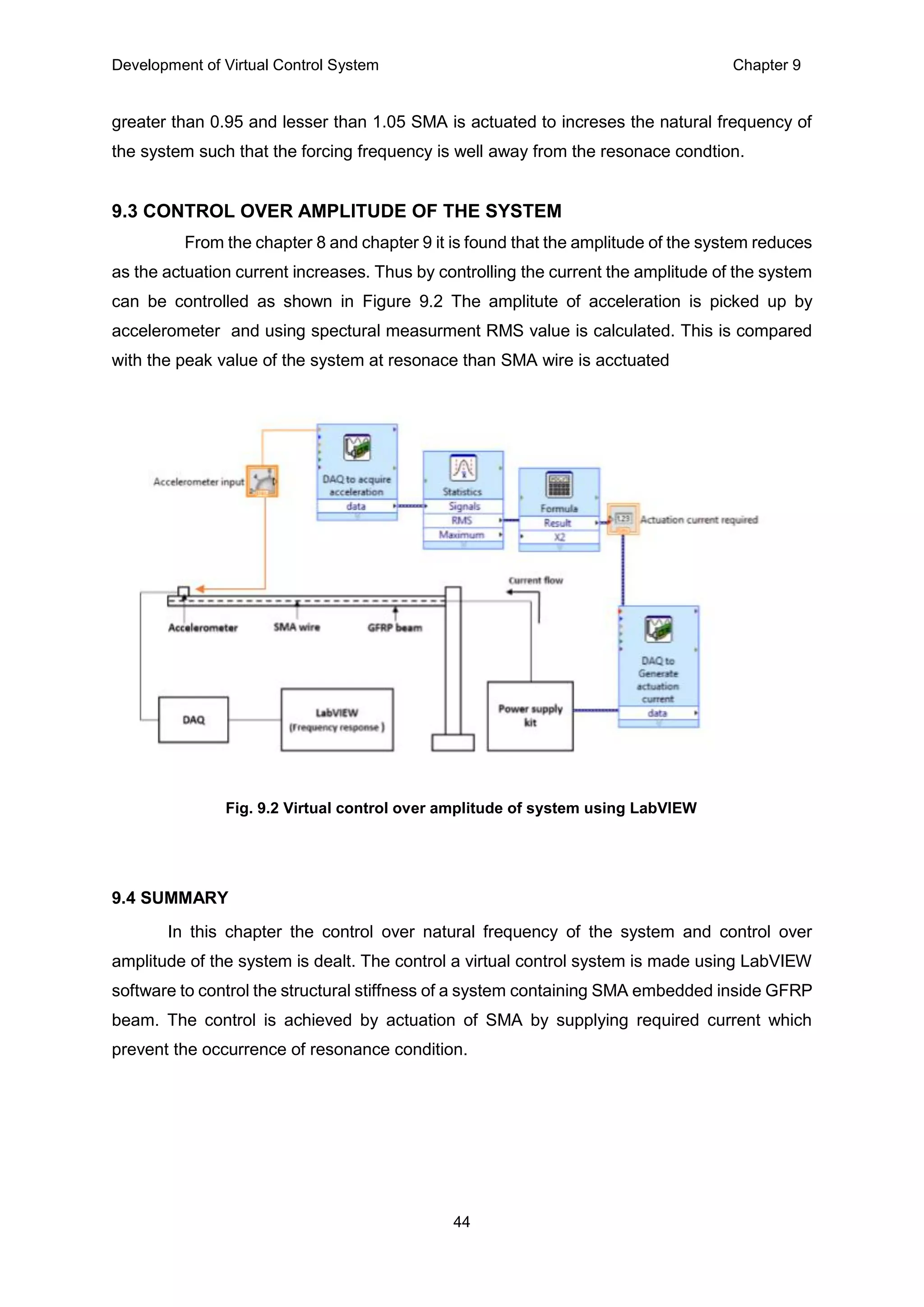

This dissertation explores the characterization of shape memory alloy (SMA) and the development of a virtual control system for monitoring SMA-based smart structures. It emphasizes the importance of identifying the Young's modulus variation of SMA with respect to actuation current, which influences the design of controlled actuators. Experimental results demonstrate significant improvements in frequency shifts and amplitude reductions, highlighting the potential of active monitoring to prevent structural failures.

![Introduction Chapter 1

1

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

1.1 SHAPE MEMORY ALLOY

Shape memory alloys (SMAs) are family of smart materials. They have the ability to

change their shape depending on their transformation temperatures. SMA, in particular nickel–

titanium alloy (Nitinol), is a metallic alloy that exhibits shape memory effect. When it deforms

at low temperatures, it has the ability to return to its predetermined shape, if heated above its

transformation temperature. The returning to its predetermined shape is the result of

crystalline structure transformation from low temperature martensite (M) phase to high

temperature austenite (A) phase. These two phases have same chemical compositions except

dissimilarity in crystallographic structures. Hence, they show dissimilarities in their thermal,

mechanical and electrical properties [1]. The high-temperature austenitic phase is more rigid

and stronger as compared with low temperature martensite phase. The low-temperature

phase is also known as twinned martensite phase where each layer is separated by a twinning

boundary. This state is highly malleable and has very low elastic limit. When external stress

is applied at this state, the material changes into detwinned variant of martensite phase that

stores generated strain. The strain can be recovered by heating the material at higher

temperatures. During strain recovery, the alloy contracts and exhibits large force against

external resistance [3]. It finally transforms into austenite phase. The thermal hysteresis

represents material transformation characteristic, which provides four distinct transformation

temperatures. Ms and Mf represent the start and finish temperatures of martensite, while As

and Af are the start and finish temperatures of austenite. It changes its status with heating

current. The shape change in the material is observed by its elastic and plastic deformation

as well as thermal expansion and contraction.

a) Mf : Martensite finish, this is the lowest temperature, below all of the material has the

soft martensitic structure

b) Ms : Martensite start, an intermediate temperature, when the martensite phase starts

to appear in the prevalently austenitic phase

c) As : Austenite start, an intermediate temperature, when the austenite phase starts to

appear in the prevalently martensitic phase

d) Af : Austenite finish, this is the highest temperature, above which all of the material has

the hard martensitic structure. Super elastic SMA are designed to work over this

temperature, while the thermal-induced memory effect finishes at this temperature.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ilovepdfmerged-180626180915/75/REPORT-ON-CHARACTERIZATION-OF-SHAPE-MEMORY-ALLOY-FOR-VIBRATION-ATTENUATION-IN-SMART-STRUCTURES-12-2048.jpg)

![Introduction Chapter 1

3

Fig. 1.1 Phase transformation in 3D stress strain temperature

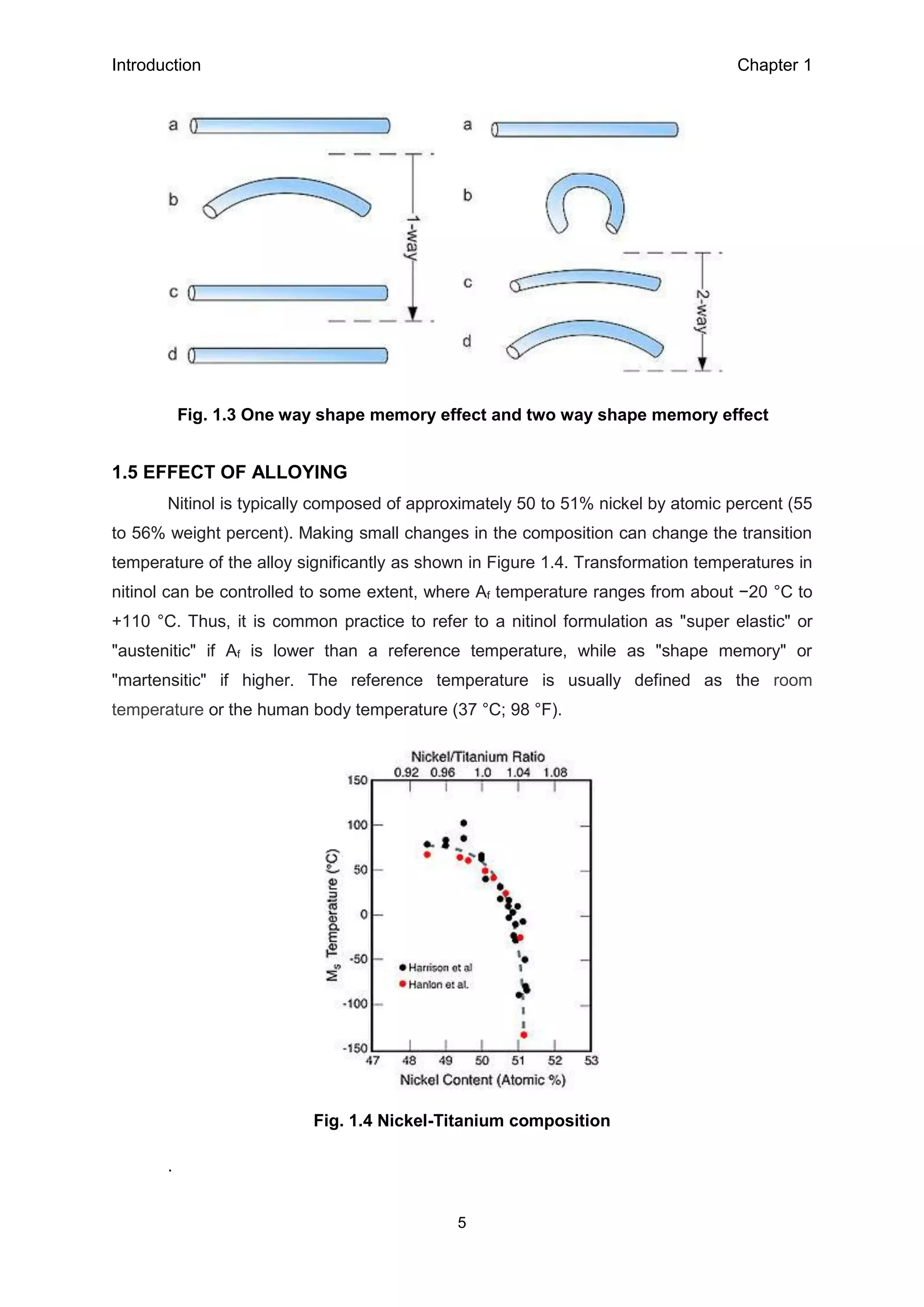

When a material changes the phase the rearranging of atoms that takes place is

referred to as transformation as shown in Figure 1.1. In solids there are two known types of

transformation: Displacive and Diffusional In diffusional transformation the rearranging of

atoms occurs across long distances [8]. The new phase formed by diffusional transformation

is of different chemical composition than that of the parent phase. In contrast, a displacive

transformation occurs by the movement of atoms as a unit, with each atom contributing a small

portion of overall displacement. In a displacive transformation the bonds between that atoms

are not broken rather than arranged, thus leaving the parent phase chemical composition

matrix intact. Martensite transformation id shape memory alloys are of displacive type and

transformation takes place between Austenite also usually referred to as the parent phase and

Martensite.

The second step of the martensitic transformation depicts the accommodation process

required as a result of shape change as shown in Figure 1.2. This process of accommodation

is called lattice invariant shear can be accomplished in two ways: Slip and Twinning.

Fig. 1.2 Lattice invariant shear accommodation (b) slip (c) twinning](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ilovepdfmerged-180626180915/75/REPORT-ON-CHARACTERIZATION-OF-SHAPE-MEMORY-ALLOY-FOR-VIBRATION-ATTENUATION-IN-SMART-STRUCTURES-14-2048.jpg)

![Introduction Chapter 1

6

1.6 APPLICATION OF SHAPE MEMORY ALLOY

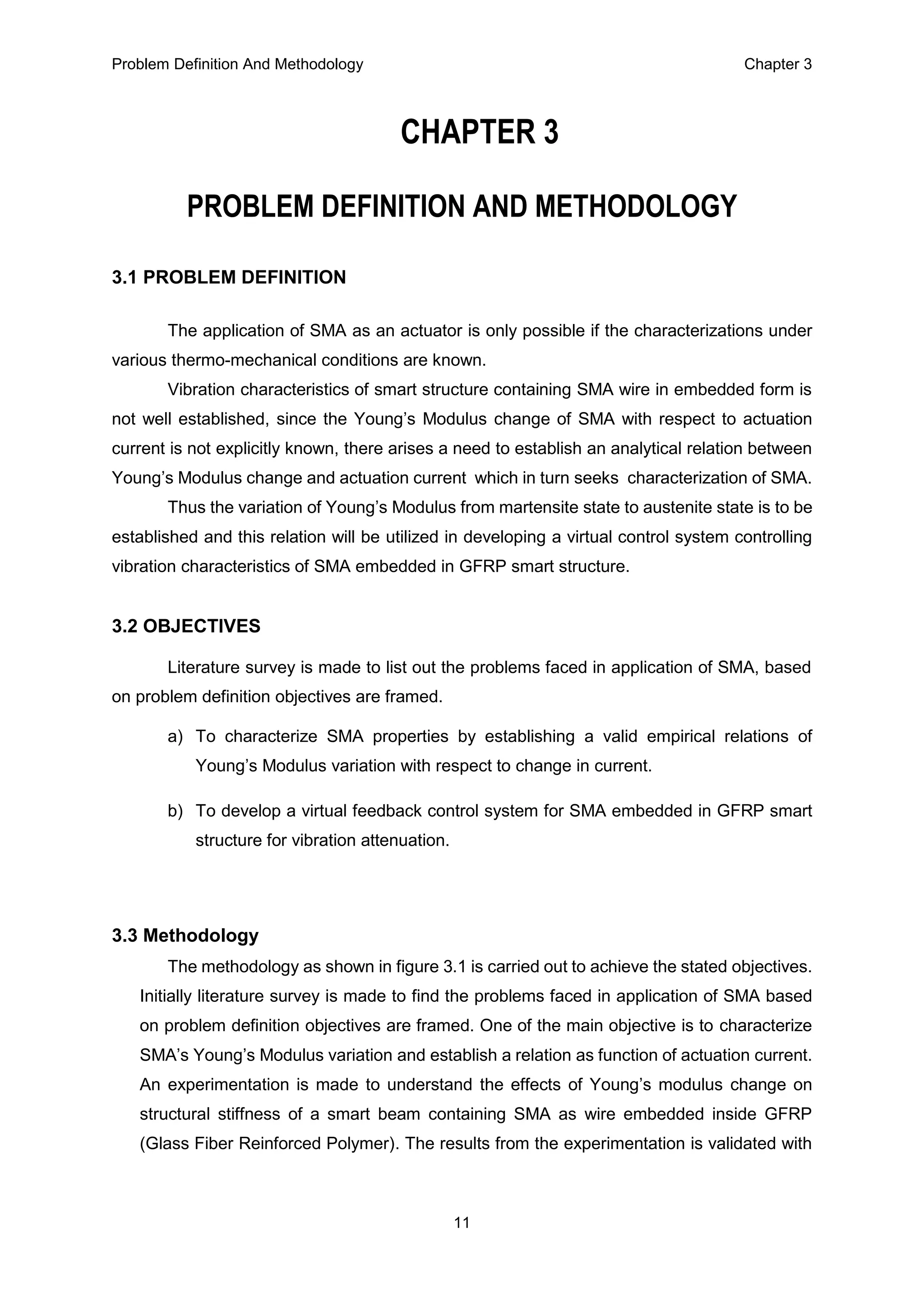

Shape memory alloys are a proven smart material with the capability to produce work

over large areas without producing residual strains. This allows the material to span many

depths of applications [7] in areas such as the mechanical, medical and aerospace fields. SMA

materials have been applied to stent operations in the medical field where its hysteretic

behavior fits the stress strain behavior of human bones and tendons while additionally

providing a resistance to radial forces. The minimum energy required for actuation of SMAs

along with the material’s ability to comply with composite materials has allowed it to thrive in

structural connections of space systems. SMAs are a prime candidate to replace bolts and

rivets in this application which can significantly degrade the properties of the structures.

Implementation of SMA materials in beam shaped structures has been confirmed to impact

the vibrational behavior of the structures both numerically and experimentally. The introduction

of the shape memory effect, whereby the shape memory alloy material acts as both a damper

and a means of variable stiffness is a novel technique for high cycle fatigue mitigation. The

impact SMAs have on the vibrational behavior of structures would greatly benefit systems

experiencing harmful flutter vibration.

1.7 Summary

Thus the inherent properties of SMA such as solid phase transformations from low

temperature, low stiffness martensite phase to high temperature, high stiffness austenite

phase, and application of SMA has been dealt in this chapter.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ilovepdfmerged-180626180915/75/REPORT-ON-CHARACTERIZATION-OF-SHAPE-MEMORY-ALLOY-FOR-VIBRATION-ATTENUATION-IN-SMART-STRUCTURES-17-2048.jpg)

![Literature review Chapter 2

7

CHAPTER 2

LITERATURE REVIEW

This chapter explains various existing works related applications of SMA and vibration

disturbances in smart structures along with control methodology.

H. N. Bhargaw et al [1] presented the thermo-electric behavior of shape memory alloy

(SMA) wire. When the wire was electrically heated above its transformation temperature by

current, a large mechanical force is exerted due to transformation in its phases. In order to make

use of SMA wire as an actuator, different parameters and their relationships were investigated.

These parameters are recoverable strain (displacement), temperature hysteresis and electrical

resistance variation under different stress levels. Optimum safe heating current was assessed

and phase transformation temperatures were estimated by heat transfer model.

Kin-tak Lau et al [2] presented the development of shape memory alloy (SMA) actuators,

in the forms of wire, thin film and stent have been found and increasingly in the fields of materials

science and smart structures and engineering. The increase in attraction for using these materials

is due to their many unique materials, mechanical, thermal and thermal-mechanical properties,

which in turn, evolve their subsequent shape memory, pseudo-elasticity and super-elasticity

properties. In this paper, a common type of SMA actuator, Nitinol wires, were embedded into

advanced composite structures to modulate the structural dynamic responses, in terms of natural

frequency and damping ratio by using its shape memory and pseudo-elastic properties.

Sia Nemat-Nasser et al [3] showed To characterize the thermomechanical response,

especially the superelastic behavior of NiTi shape-memory alloys (SMAs) at various temperatures

and strain rates, we have performed a series of both quasi-static and dynamic uniaxial

compression tests on cylindrical samples, repeated dynamic tests of the alloy produce smaller

changes in the shape of the superelastic loop and in the dissipated energy than do the quasi-

static cyclic tests; and the superelastic behavior of this material has stronger sensitivity to

temperature than to strain rate; at very high loading rates

Toshibumi Fukuta et al [4] Mechanical properties of shape memory alloy (hereinafter

referred to as SMA) bars were investigated for their structural use of buildings and two examples](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ilovepdfmerged-180626180915/75/REPORT-ON-CHARACTERIZATION-OF-SHAPE-MEMORY-ALLOY-FOR-VIBRATION-ATTENUATION-IN-SMART-STRUCTURES-18-2048.jpg)

![Literature review Chapter 2

8

of SMA in super elasticity phase applied to structural elements are proposed. The static and

dynamic loading tests on SMA bars demonstrated that the stress strain curve for tensile stress is

completely different from that for compressive stress, irrespective of whether the load is static or

dynamic in nature. Super elasticity was clearly evident under tensile strain of up to around 5%,

but not under compressive strain, due to the presence of residual strain. The yield strength in

compression is almost two times of tension yielding under the strain rate tested.

Gupta. K et al [5] have discussed the use of nitinol [shape memory alloy (SMA)] wires in

the fiber-reinforced composite shaft, for the purpose of modifying shaft stiffness properties to

avoid such failures, is discussed. A setup has been developed to fabricate the composite shaft

(made of fiber glass and epoxy resin) embedded with pre-stressed SMA wires. Experiments have

been carried out on the shaft to estimate the changes in the natural frequency of the composite

shaft due to activation and deactivation of SMA wires. The comparison of the experimental results

with the established analytical results indicates feasibility of vibration control using the special

properties of SMA wires.

Yuvaraja. M et al [6] have presented the significance of shape memory alloy in vibration

control. They have developed a shape memory alloy spring based dynamic vibration absorber

with the help of microcontroller. The vibration was controlled for the range of frequencies from 21

Hz to 27 Hz in case of cantilever beam, which was used as a representation model. They have

demonstrated that multiple SMA springs can be used effectively to control vibration. They have

tested the performance of developed SMA based actively tuned dynamic vibration absorber in

piping application, and found out that the SMA is capable of controlling the amplitude of vibration

for varying excitation frequencies. The vibration in the pipeline was reduced by around 60 % using

SMA based adaptively tuned dynamic vibration absorber.

Jaronie et al [7] describes the attributes of SMAs that make them ideally suited to

actuators in various applications, and addresses their associated limitations to clarify the design

challenges faced by SMA developers. This work provides a timely review of recent SMA research

and commercial applications, with over 100 state-of-the-art patents; which are categorized against

relevant commercial domains and rated according to design objectives of relevance to these

domains (particularly automotive, aerospace, robotic and biomedical). Although this work

presents an extensive review of SMAs, other categories of SMMs are also discussed; including a

historical overview, summary of recent advances and new application opportunities.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ilovepdfmerged-180626180915/75/REPORT-ON-CHARACTERIZATION-OF-SHAPE-MEMORY-ALLOY-FOR-VIBRATION-ATTENUATION-IN-SMART-STRUCTURES-19-2048.jpg)

![Literature review Chapter 2

9

Schetky, L.M et al [8] investigates the torsional behavior of Ni-rich Ni50.3Ti29.7Hf20

high-temperature shape memory alloy tubes under pure torsion loading. Torque tubes with

varying geometry including outer diameter, wall thickness, and length were subjected to constant-

torque thermal cycling at stresses ranging from 0–500 MPa (0–175 N-m). It was found that the

wall thickness had a notable effect on the transformation temperatures where thick-walled tubes

transformed at lower temperatures when compared to the thin-walled form.

B.-S. Jung et al [9] investigates SMA wire embedded hybrid composite to have a larger

displacement than a SMA wire embedded single composite. The hybrid composite is designed

with a n-shape and it is comprised of three parts with different stiffness materials, GFRP with

higher stiffness at both ends and silicone rubber with lower stiffness in the middle to increase the

displacement range of the structure. The SMA wire embedded hybrid composite can be actuated

by applying an electric current through the embedded SMA wire. The fabricated composite was

mechanically fastened to prevent separation between the wire and the composite laminae

induced by temperature rise of the wire. The displacement of SMA wire embedded hybrid

composite was examined by measuring the radius of curvature.

Teroko Aoki et al [10] have investigated the characteristics of the damping produced by

the shape recovery force of the smart matrix composite made of epoxy resin with embedded fibers

of Ni-Ti SMA (Shape Memory Alloy) which are tested by vibration experiments using the cantilever

beam method. The characteristics are examined with calculated loss factors obtained by

measuring resonance frequencies and attenuation characteristics. Their study reveals that the

smart matrix composite in this research has characteristics of the damping material by shifting its

resonance frequencies.

Yuvaraja M et al [11] In this paper work Shape memory alloy and piezoelectric based

composites are presented for investigating the vibration characteristics. In former case, GFRP

beam modeled in cantilevered configuration with externally attached SMAs. In later case, GFRP

beam with surface bonded PZT patches are analysed for its vibration characteristics. The

experimental work is carried out for both cases in order to evaluate the vibration control of flexible

beam for first mode, also to find the effectiveness of the proposed actuators and verified

numerically. As a result the vibration characteristic of GFRP beam is more effective when SMA is

used as an actuator.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ilovepdfmerged-180626180915/75/REPORT-ON-CHARACTERIZATION-OF-SHAPE-MEMORY-ALLOY-FOR-VIBRATION-ATTENUATION-IN-SMART-STRUCTURES-20-2048.jpg)

![Literature review Chapter 2

10

Irschik, H. et al [12] This paper presents an investigation into design optimization of

actuator patterns for static shape control of composite plates with piezoelectric actuator patches.

An energy optimization based method for finding the optimal control voltages that can actuate a

structure shape close to the desired one within a given error is described. Moreover, a voltage

limitation for each actuator is also imposed to keep its control voltage within a practical range.

Finally, illustrative examples are given to demonstrate the effectiveness of the present equivalent

element and the design optimization scheme. Numerical results show that satisfactory static

shape control can be achieved even after a number of actuators are removed.

Hashemi S.M.T et al [13] has analyzed the dynamical behavior of simply supported and

clamped-free beams and observed the temperature increase causes an increment in stresses of

star and finish of transformation, as well as decrease in hysteresis level and presence of different

elastic modules at austenite and martensite phases, causes a change in system stiffness and

consequently variation in natural frequencies, which leads to an escape from resonance

conditions has been shown clearly.

Gangbing Songa et al [14] have given the design and experiment results of active

position control of shape memory alloy (SMA) wires actuated composite beam. The potential

applications of the experiment included the thermo-distortion compensation for precession space

structure, stem shape control for submarines, and flap shape control for aeronautical applications.

A new control approach including a feed forward action, a PD control action, and a robust

compensator has been developed.

2.1 Literature Outcomes

From the literature survey, vibrational problems in structural applications are one the major

factor to consider and it has a vast scope of development. In order to control this vibration, various

methods of vibration control were studied. Shape memory alloys in the form of actuator wire have

been used for active position control in various application but vibration characteristics of smart

structure containing SMA wire in embedded form is not well established, since the Young’s

modulus change of SMA with respect to actuation current is not explicitly known, there arises a

need to establish an analytical relation between Young’s modulus change and actuation current

which in turn seeks characterization of SMA.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ilovepdfmerged-180626180915/75/REPORT-ON-CHARACTERIZATION-OF-SHAPE-MEMORY-ALLOY-FOR-VIBRATION-ATTENUATION-IN-SMART-STRUCTURES-21-2048.jpg)

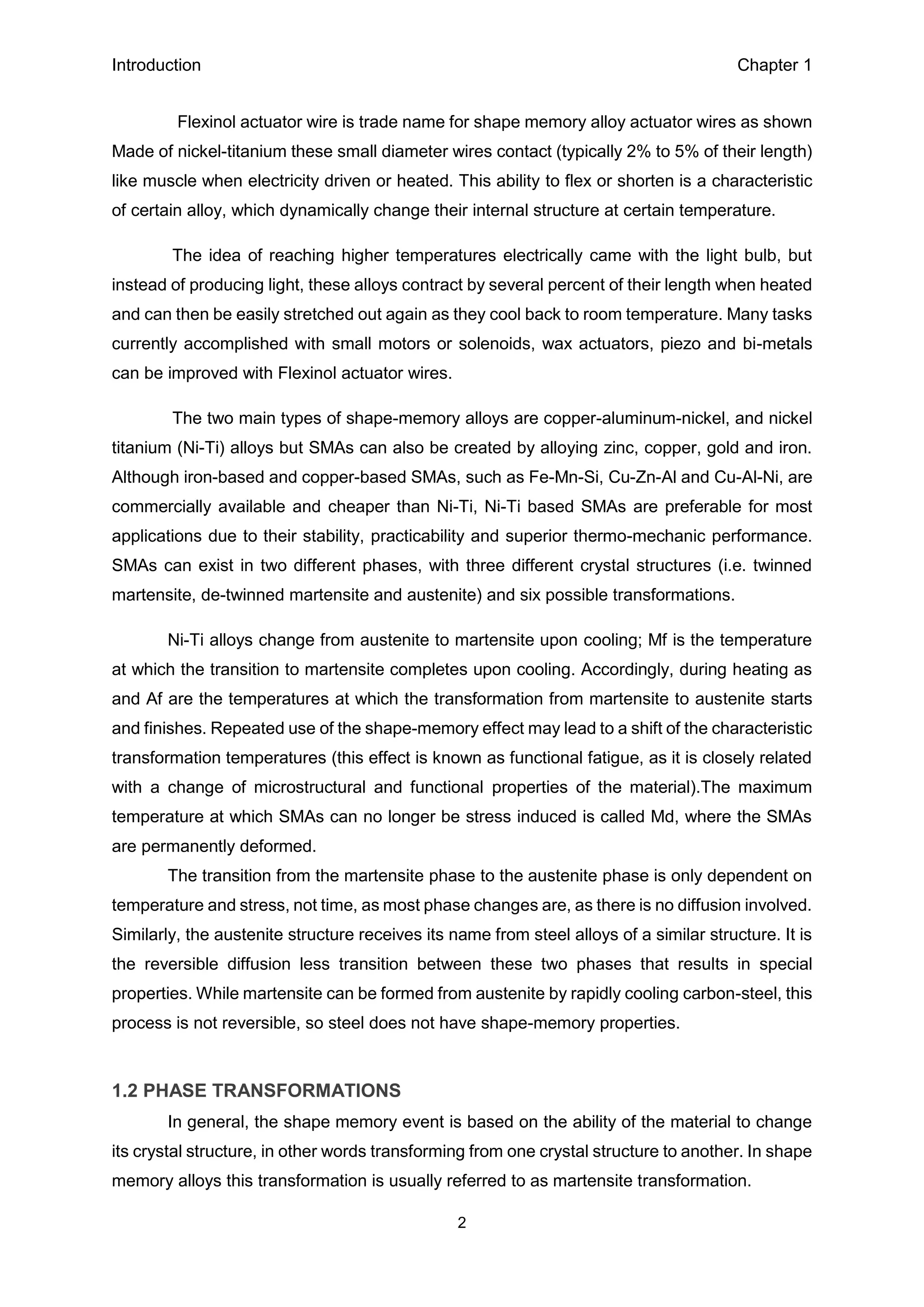

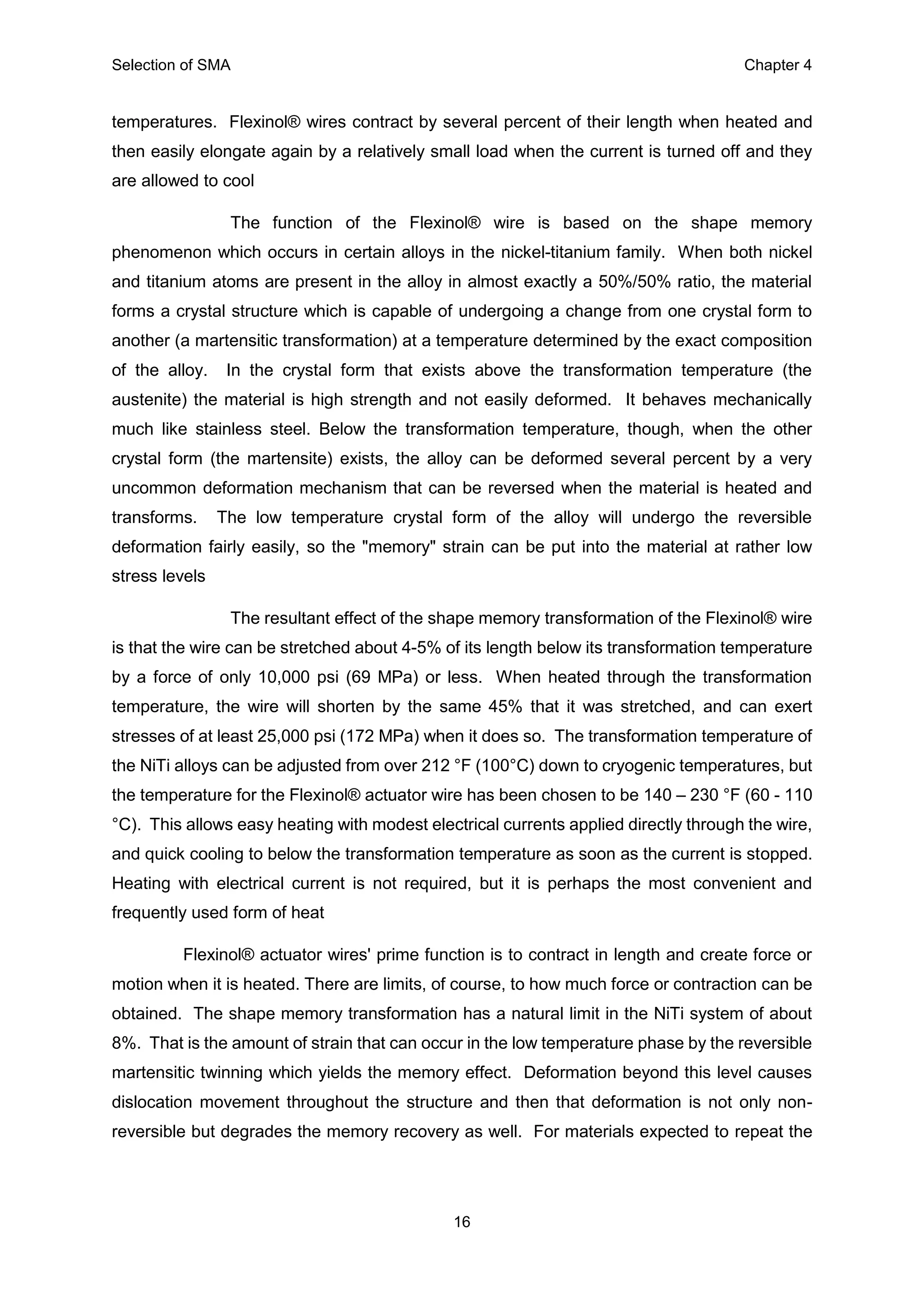

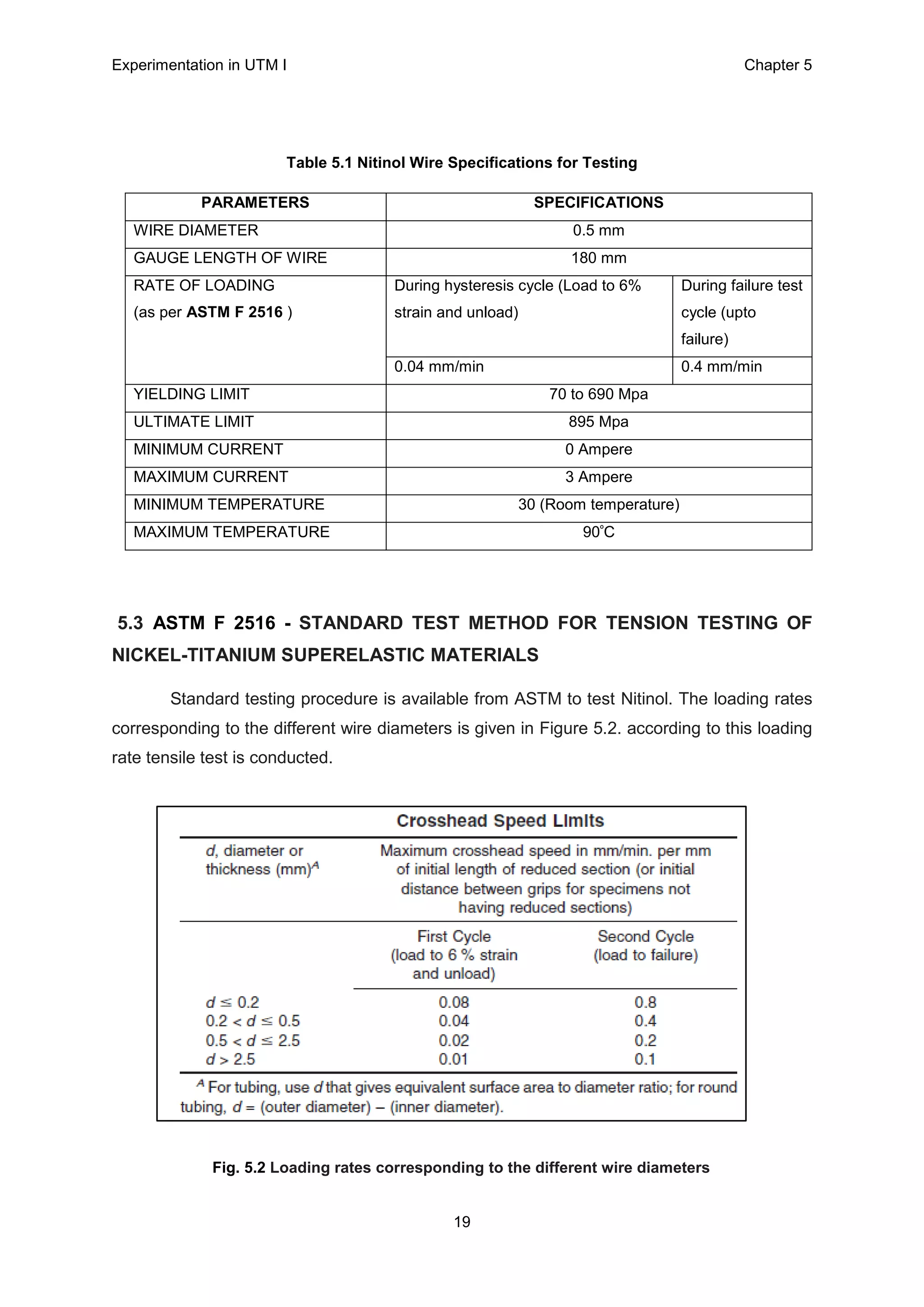

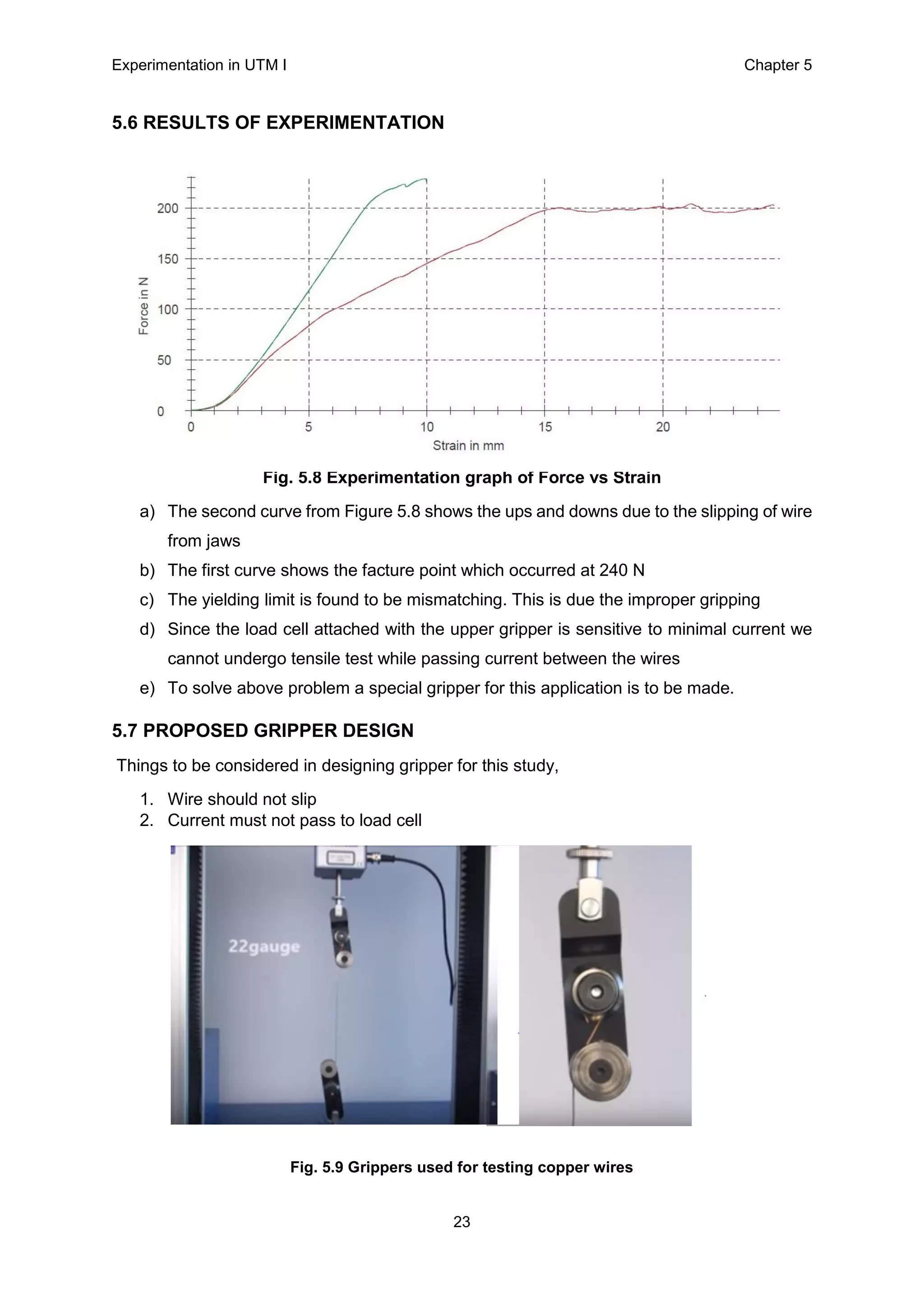

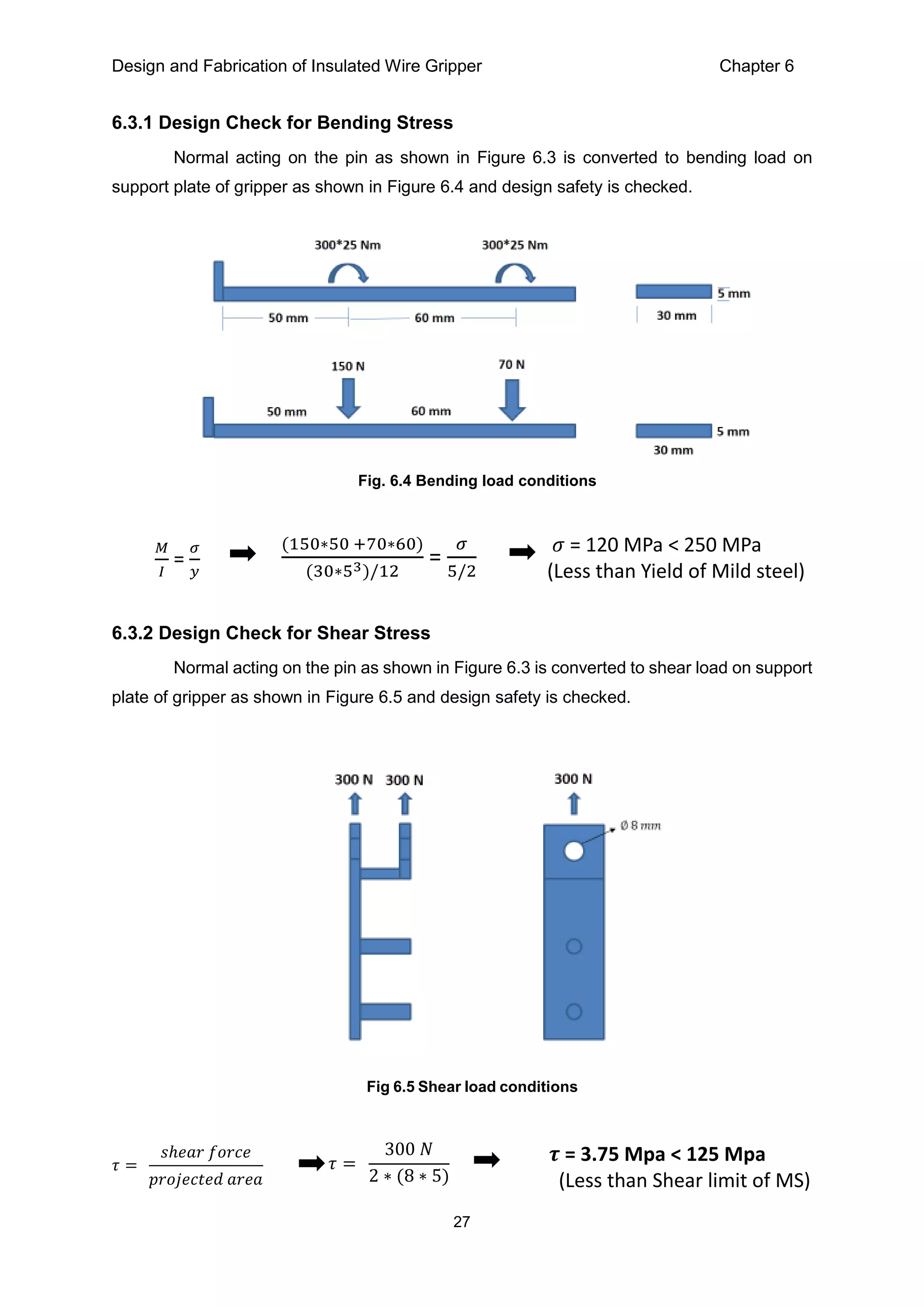

![Experimentation in UTM Ι Chapter 5

20

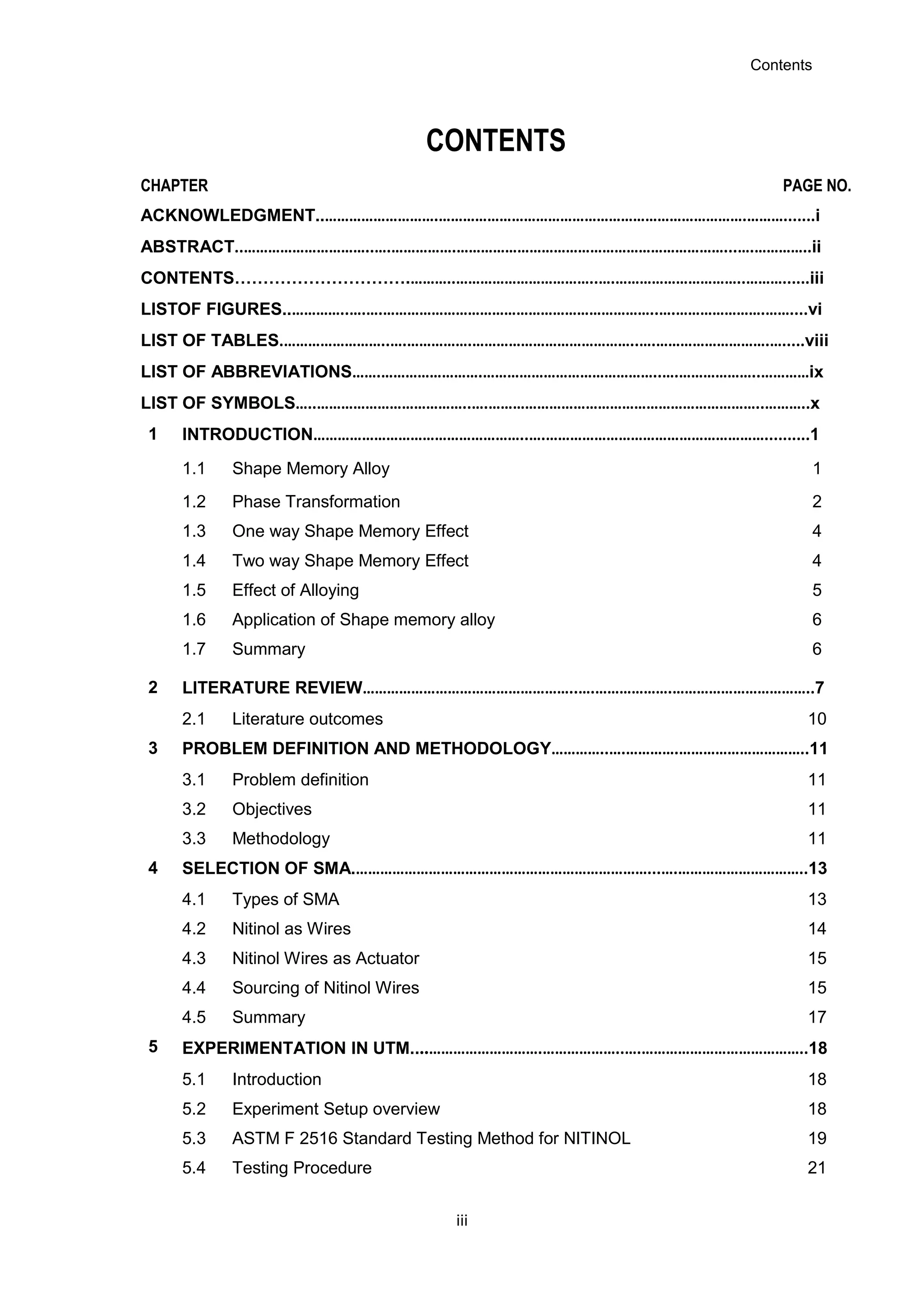

Fig. 5.3 Typical Stress Strain diagram of superelastic Nitinol

a) Lower Plateau Strength (LPS)—the stress at 2.5 % strain during unloading of the

sample, after loading to 6 % strain as referred in Figure 5.3.

b) Residual Elongation, Elr[%]—the difference between the strain at a stress of 7.0 MPa

during unloading and the strain at a stress of 7.0 MPa during loading .

c) Uniform Elongation, Elu[%]—the elongation determined at the maximum force

sustained by the test piece just prior to necking, or fracture, or both.

d) Upper Plateau Strength (UPS)—the stress at 3 % strain during loading of the sample.

ZWICK / ROEL 2.5 KN is a German made Universal Testing Machine as shown in Figure

5.4 used of tensile test of the wire specimen.

Fig. 5.4 ZWICK / ROEL 2.5 KN UTM](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ilovepdfmerged-180626180915/75/REPORT-ON-CHARACTERIZATION-OF-SHAPE-MEMORY-ALLOY-FOR-VIBRATION-ATTENUATION-IN-SMART-STRUCTURES-31-2048.jpg)

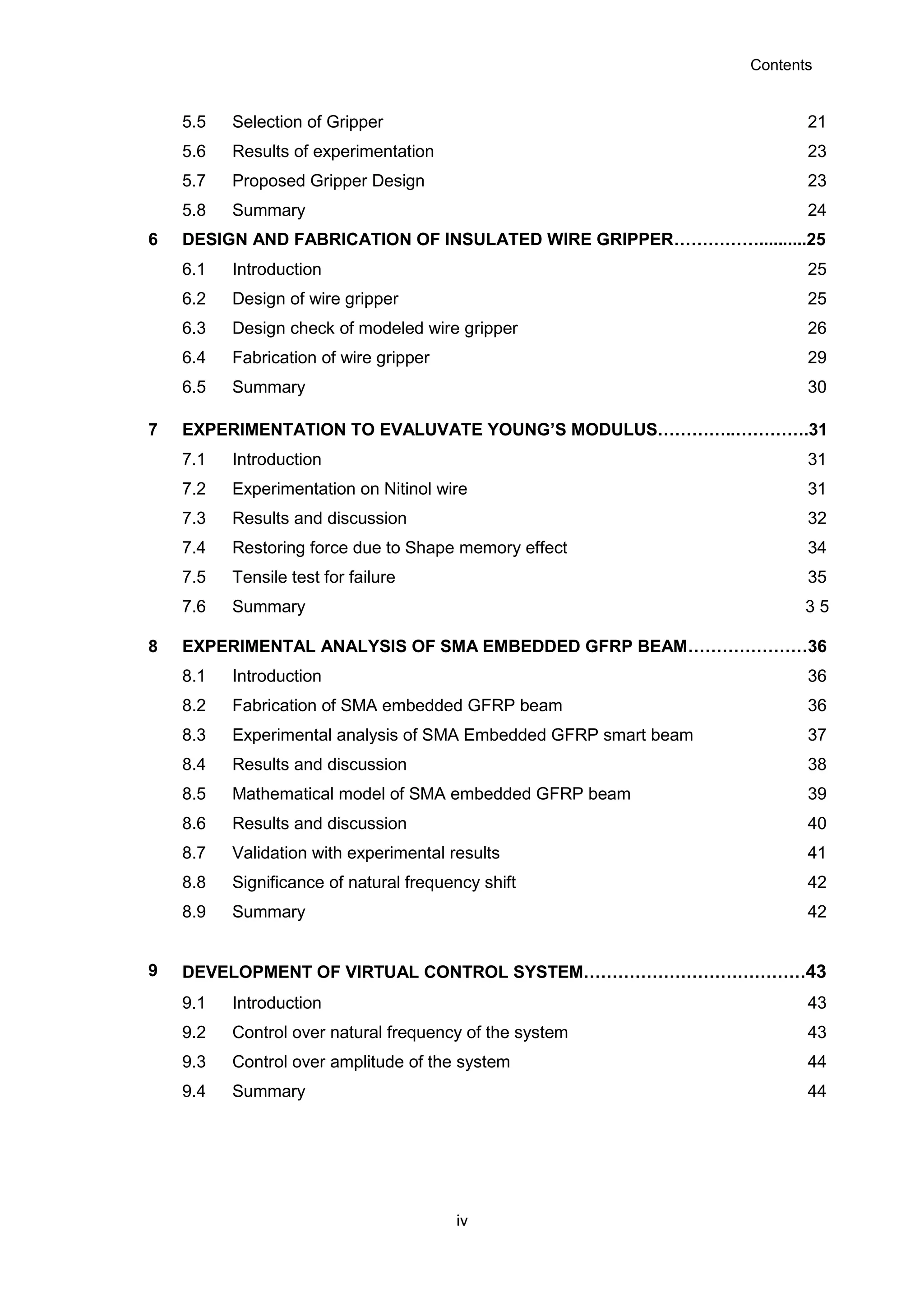

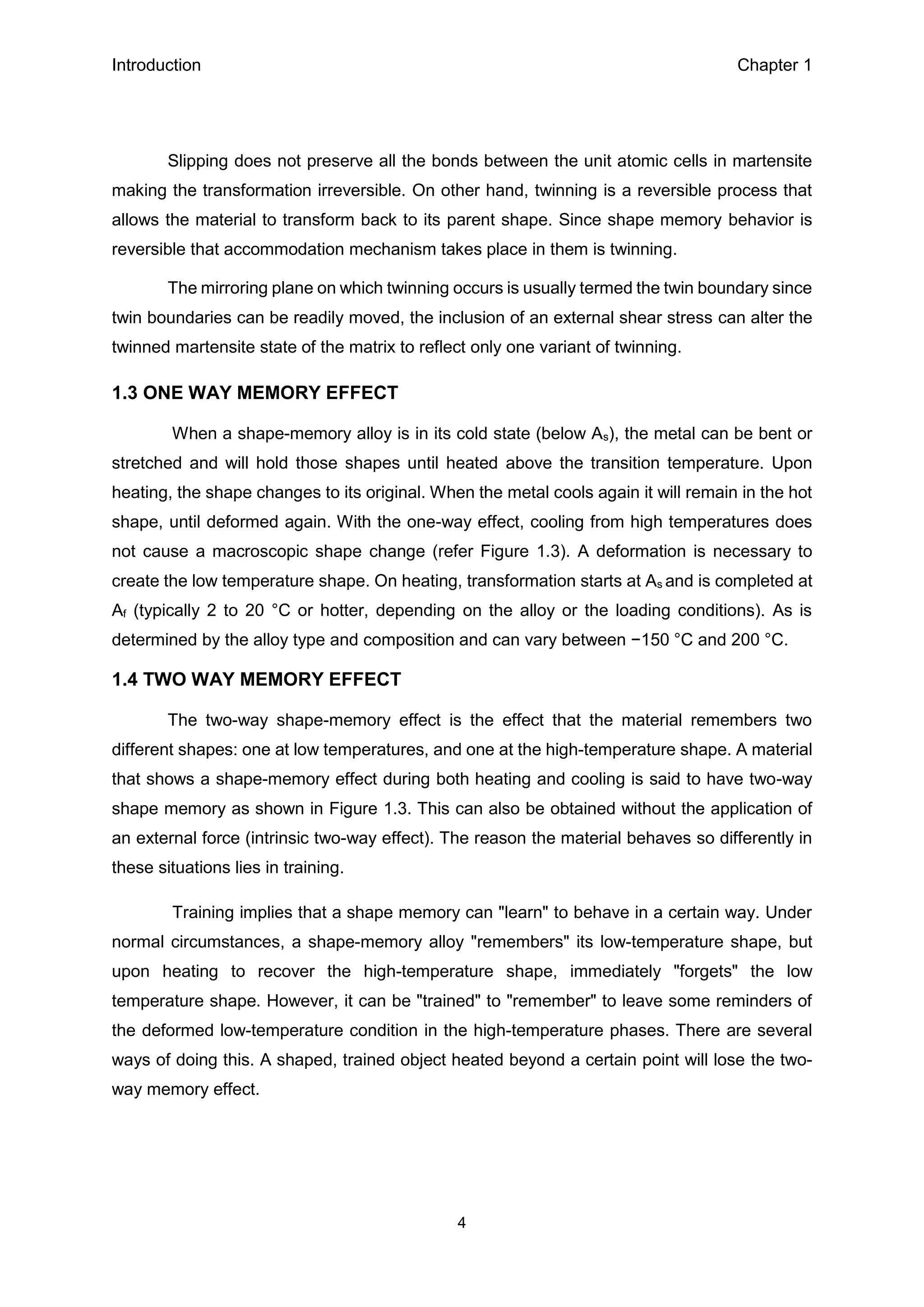

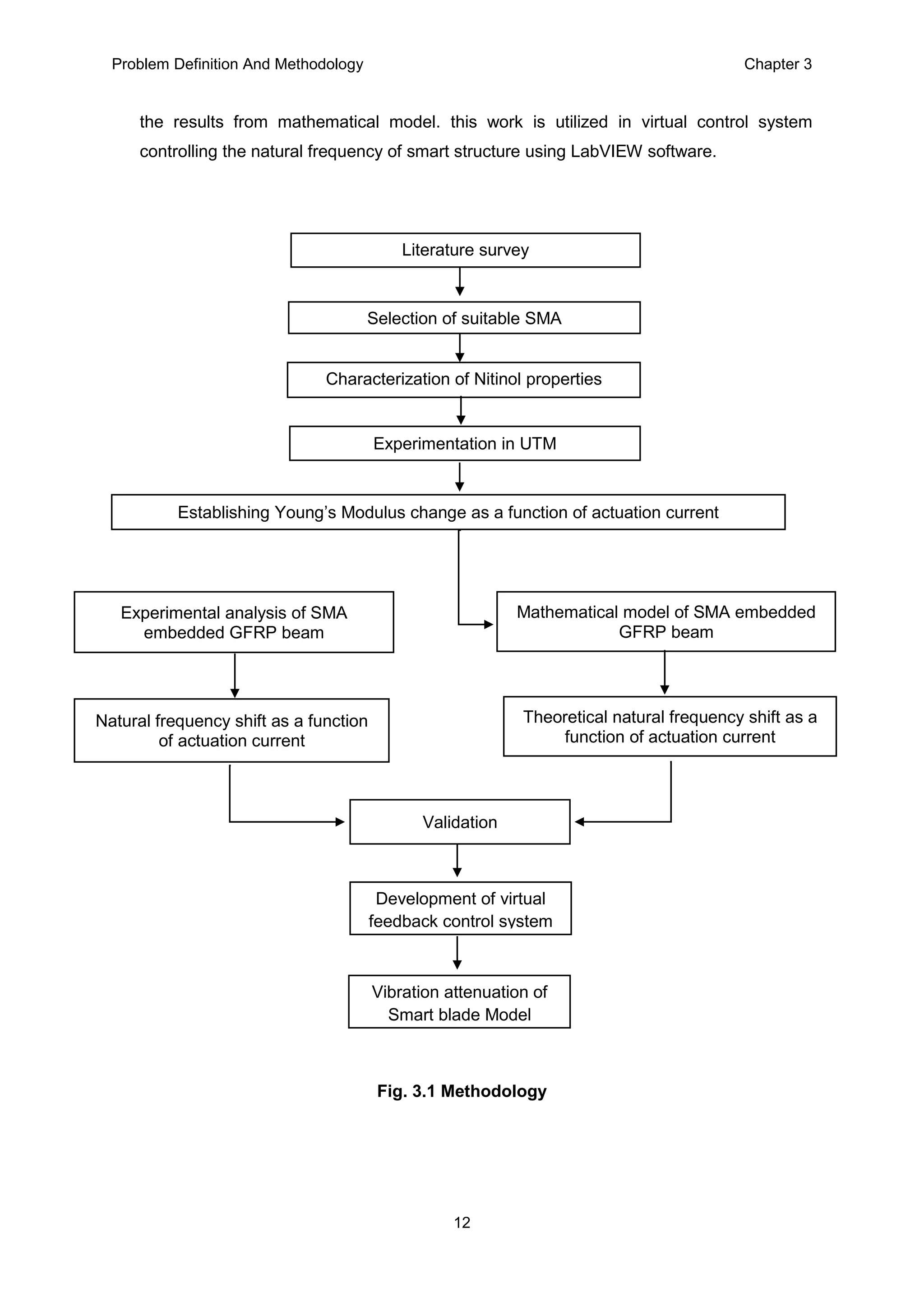

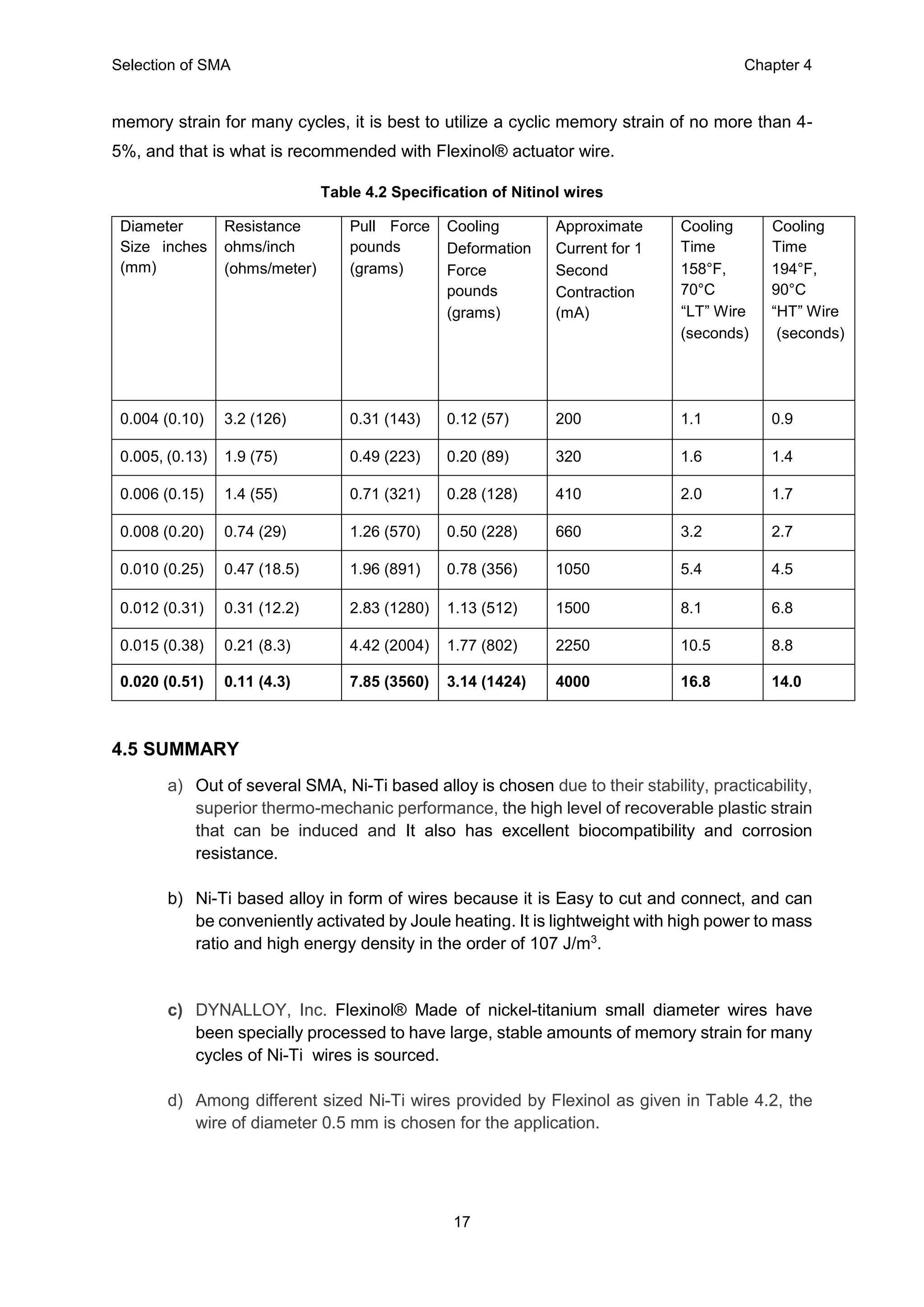

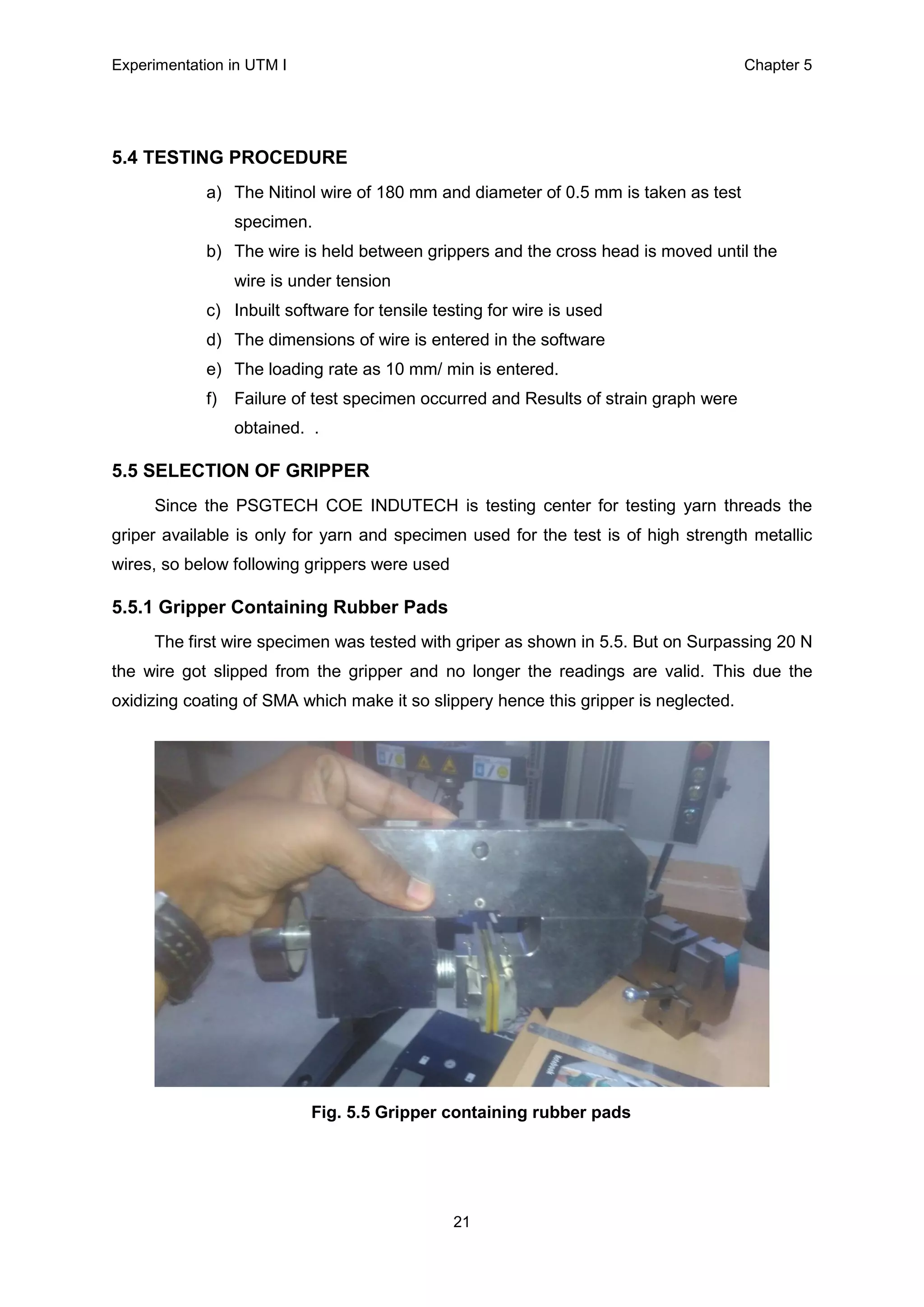

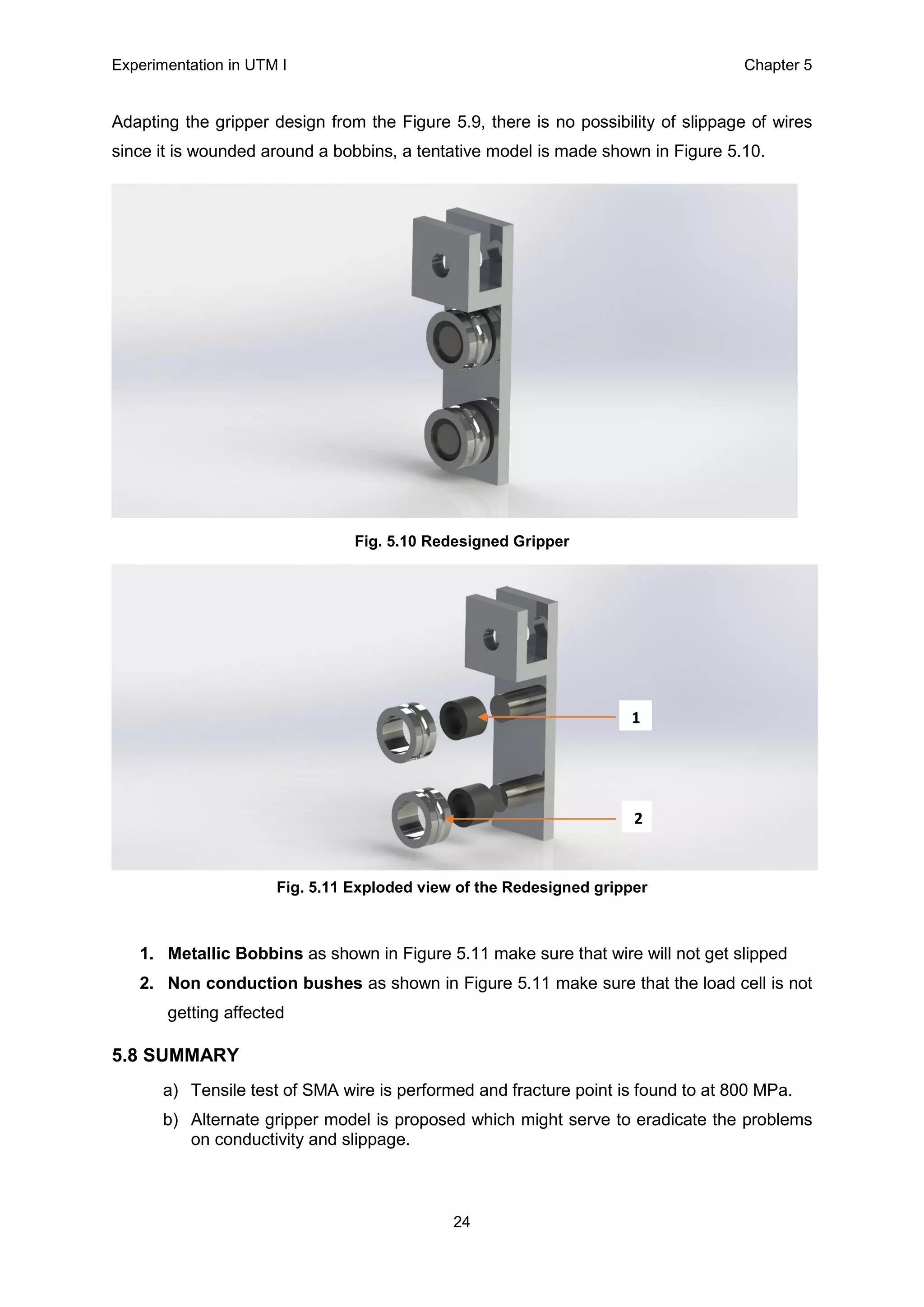

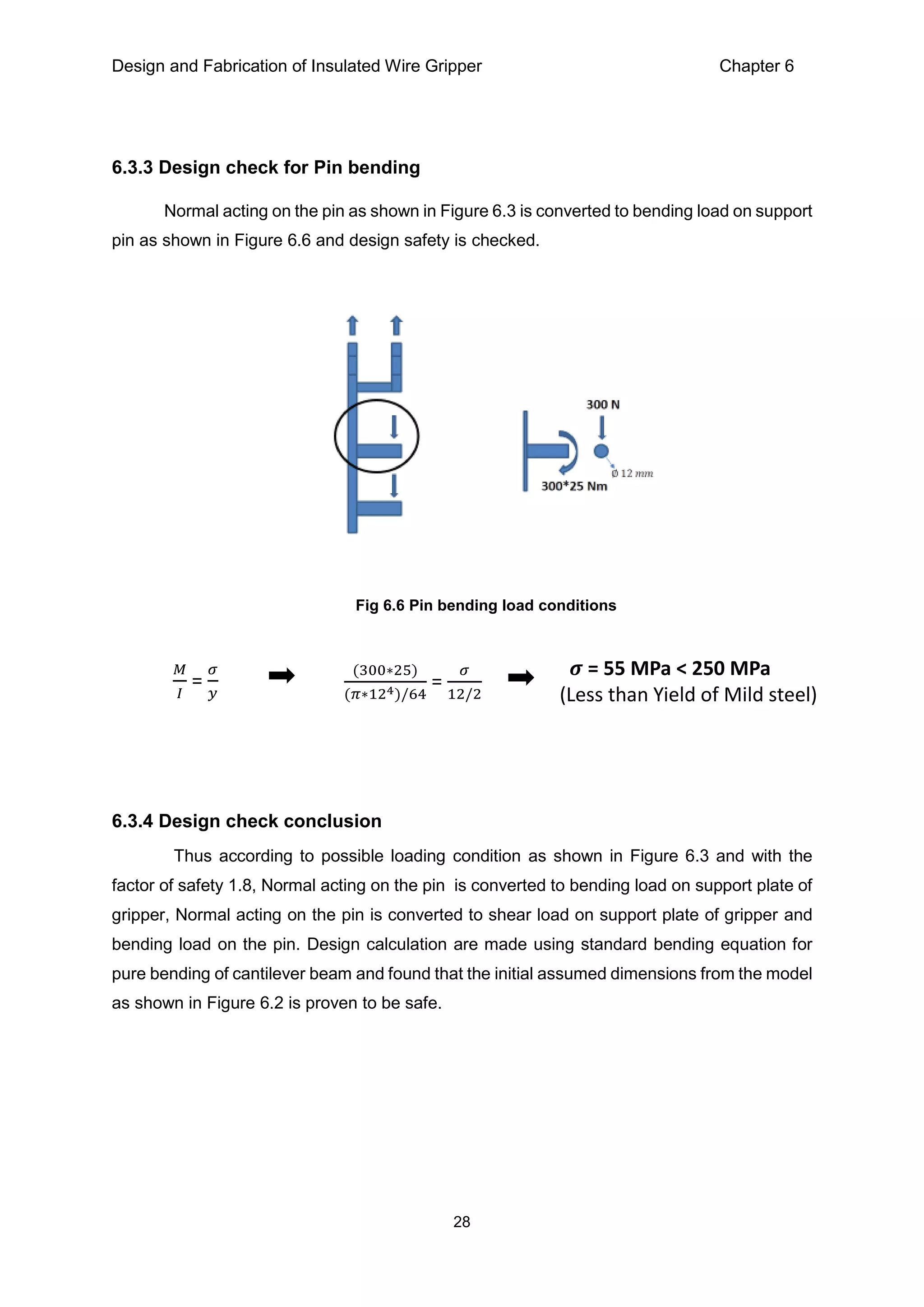

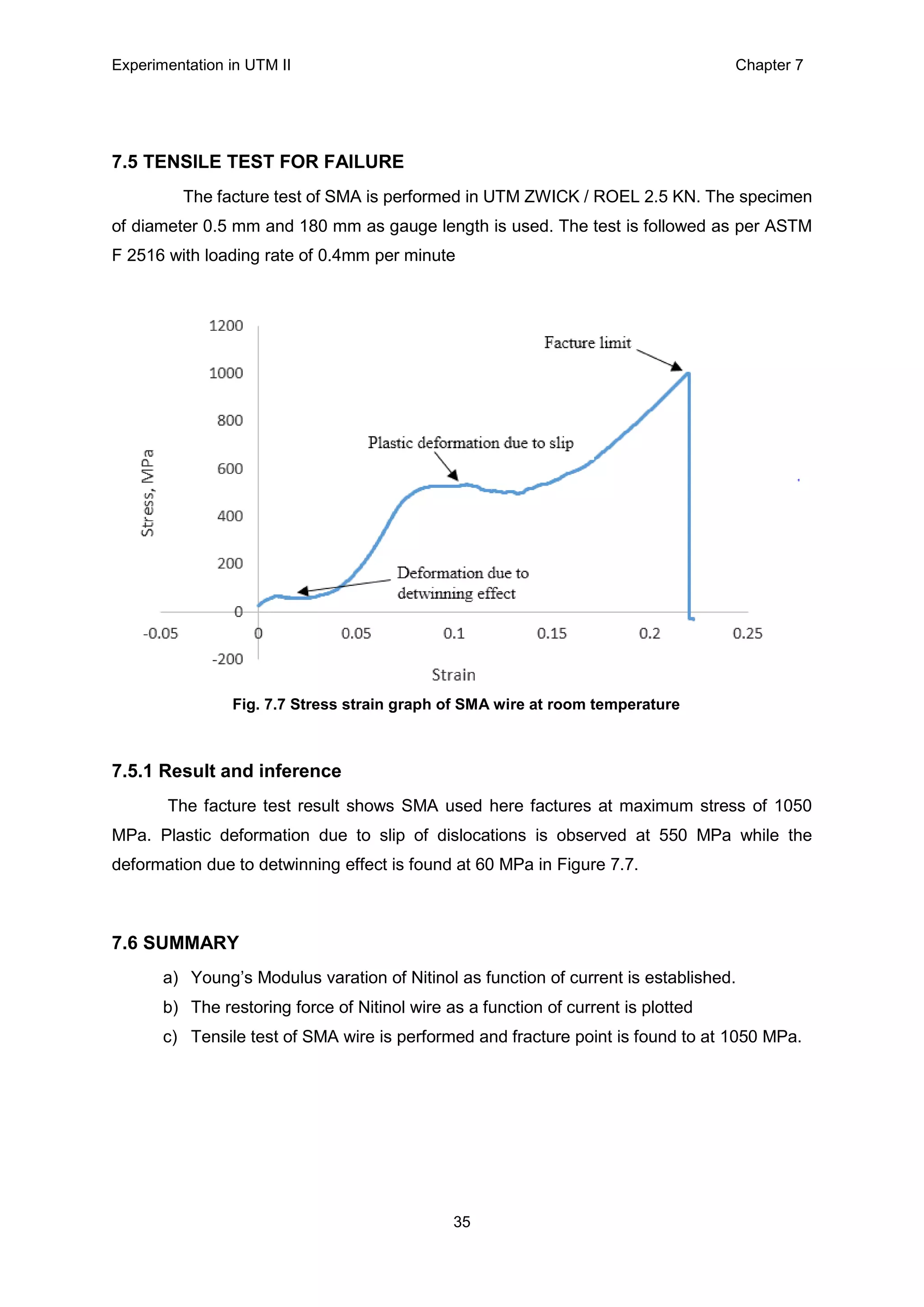

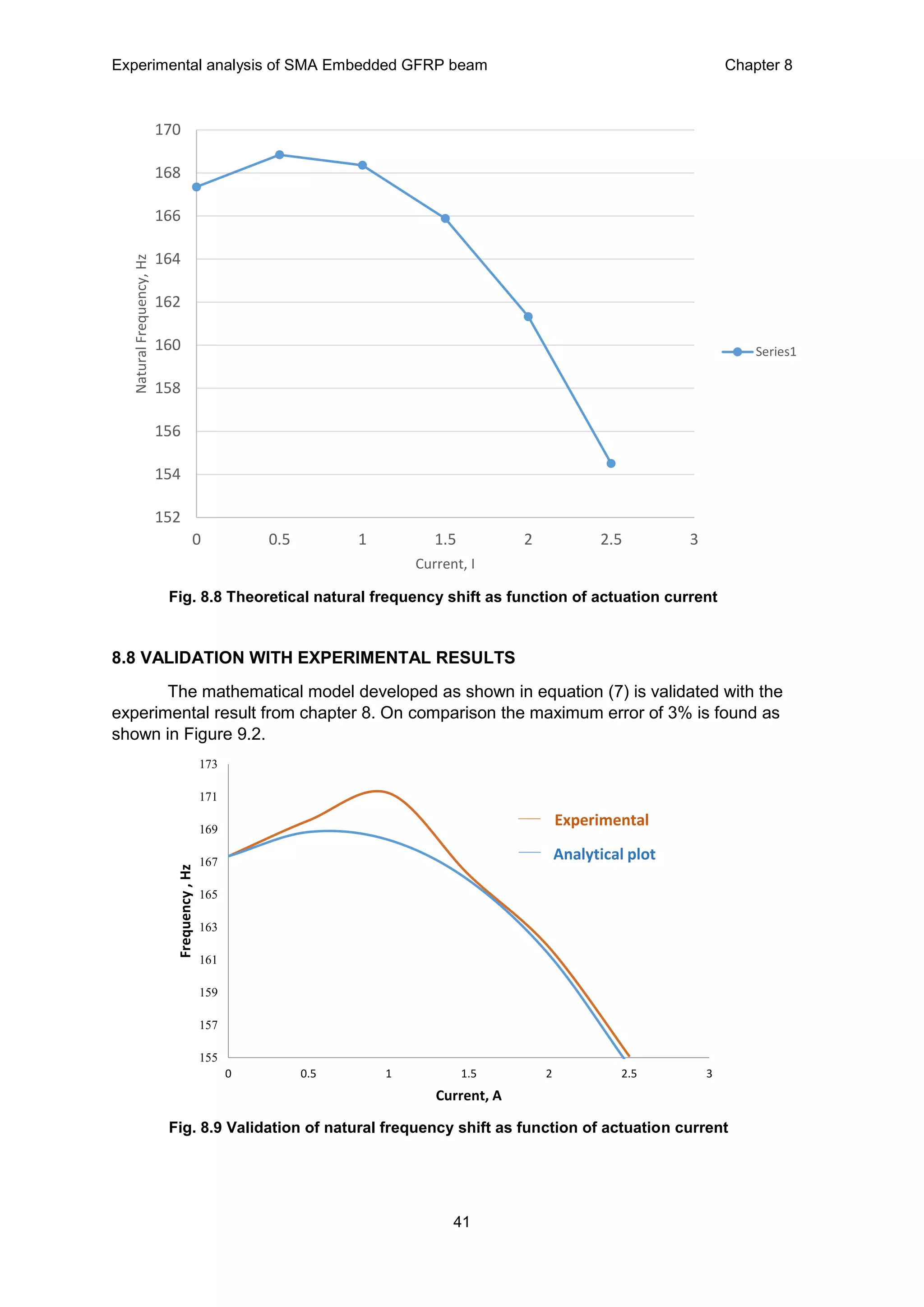

![Experimental analysis of SMA Embedded GFRP beam Chapter 8

39

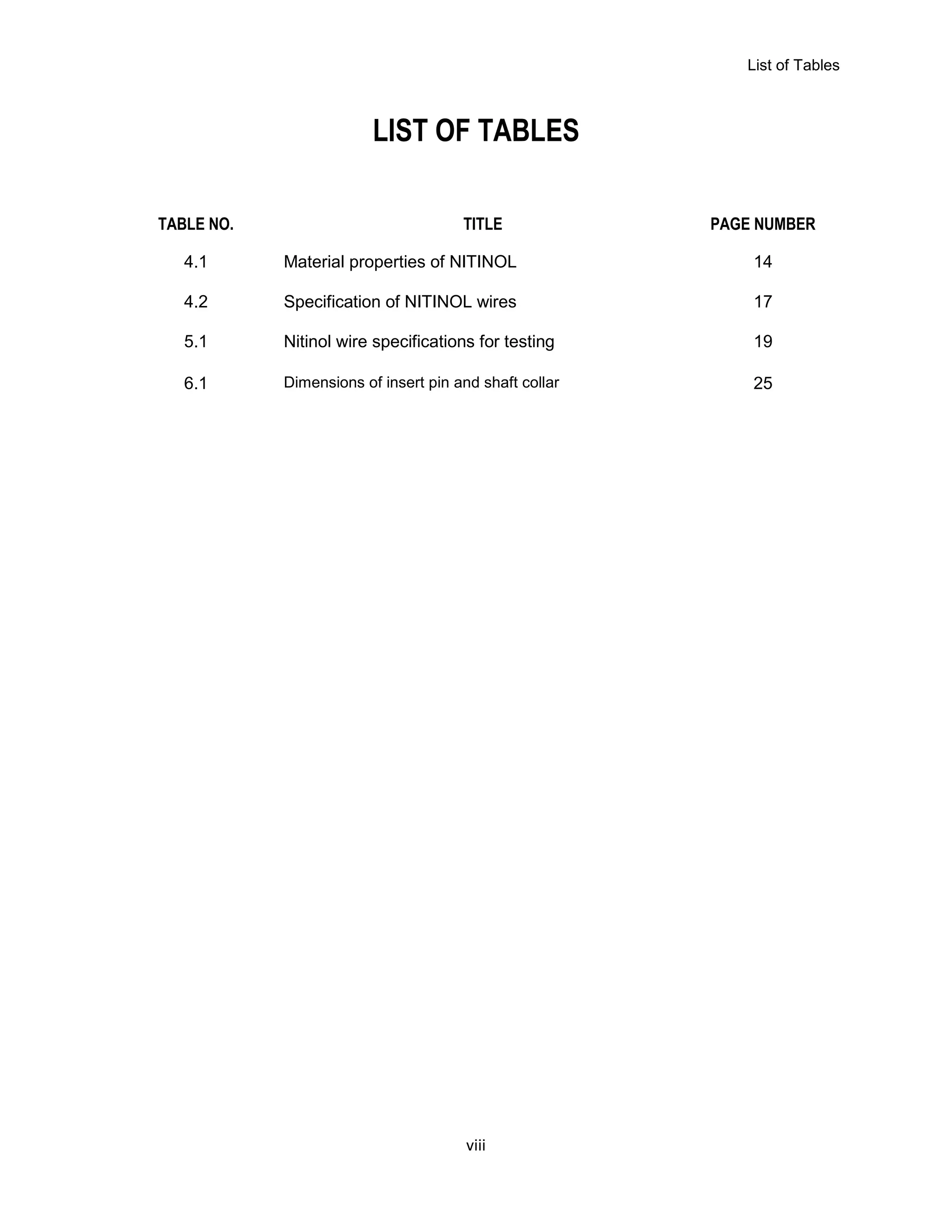

reason that the overall young’s modulus of smart beam depends on both young’s modulus of

GFRP and young’s modulus of SMA.

From the prior experimental study of SMA in chapter 7 shows that as current increases the

young’s modulus of SMA increases due to its solid phase transformation. Once the current

exceeding 1 ampere the overall temperature of beam increases but young’s modulus of GFRP

decreases with increases in temperature. Thus stiffness of overall beam reduces and

decreases in natural frequency is observed in Figure 8.7.

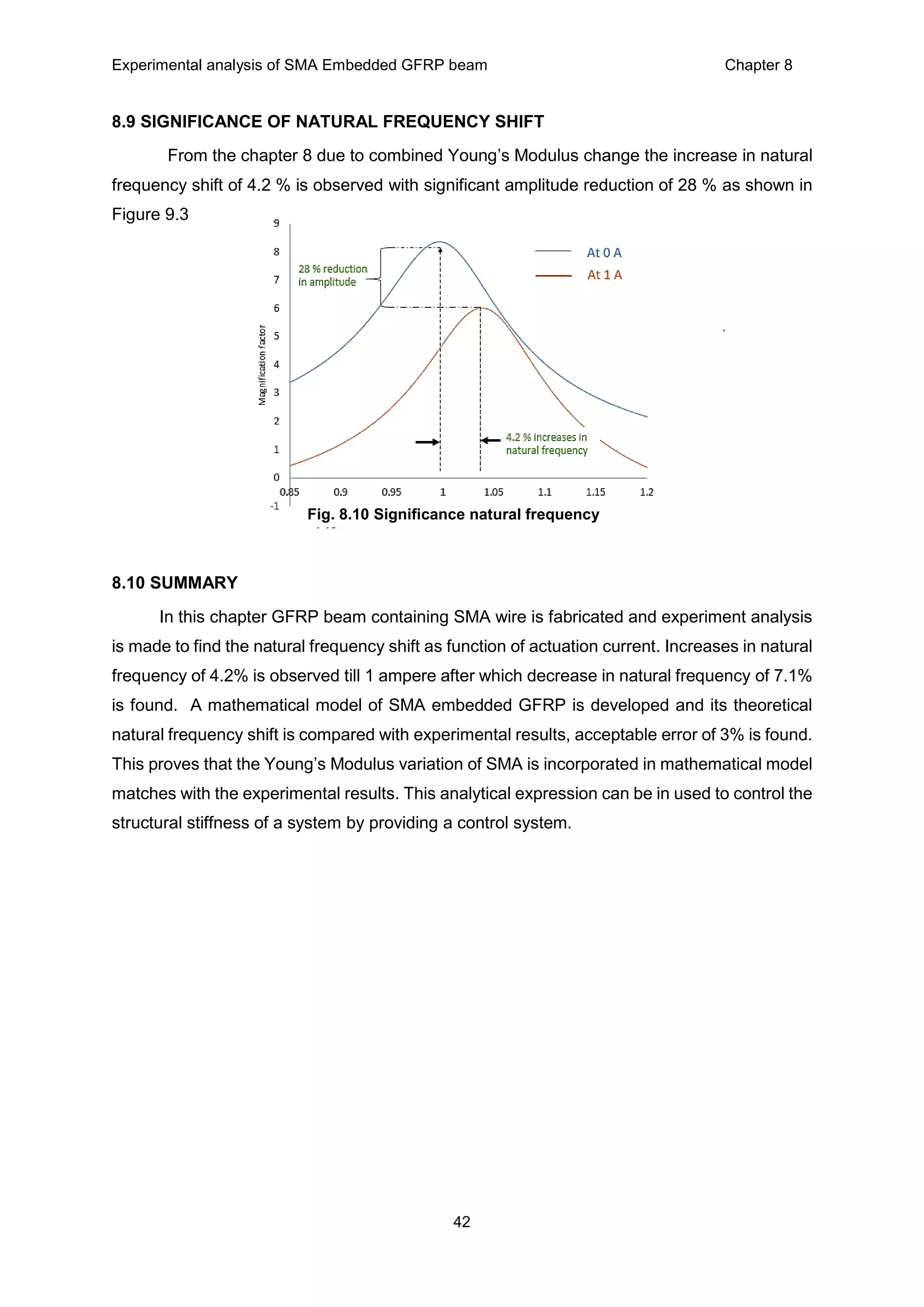

8.6 MATHEMATICAL MODEL OF SMA EMBEDDED GFRP BEAM

In chapter 8 experimental analysis on natural frequency shift of SMA embedded GFRP

beam is presented. A mathematical model is developed to find theoretical natural frequency

shift and it is validated with experimental analysis.

The assumptions made to develop this mathematical model such as the beam is

considered to be cantilever beam subjected to pure bending, and the material properties of

SMA and GFRP is isotropic in nature. For a simple elastic beam problem with uniform

cross section the natural frequency is given by [9],

f(n) =

𝟏

𝟐𝝅

√

𝟑𝑬(𝒄𝒐𝒎𝒃𝒊𝒏𝒆𝒅)𝑰

𝑳 𝟑 𝒎

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………. (2)

Fig. 8.7 Natural frequency of smart beam as a function of current.

155

157

159

161

163

165

167

169

171

173

0 0.5 1 1.5 2 2.5 3

Frequency,Hz

Current, A

Experimental plot](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ilovepdfmerged-180626180915/75/REPORT-ON-CHARACTERIZATION-OF-SHAPE-MEMORY-ALLOY-FOR-VIBRATION-ATTENUATION-IN-SMART-STRUCTURES-50-2048.jpg)

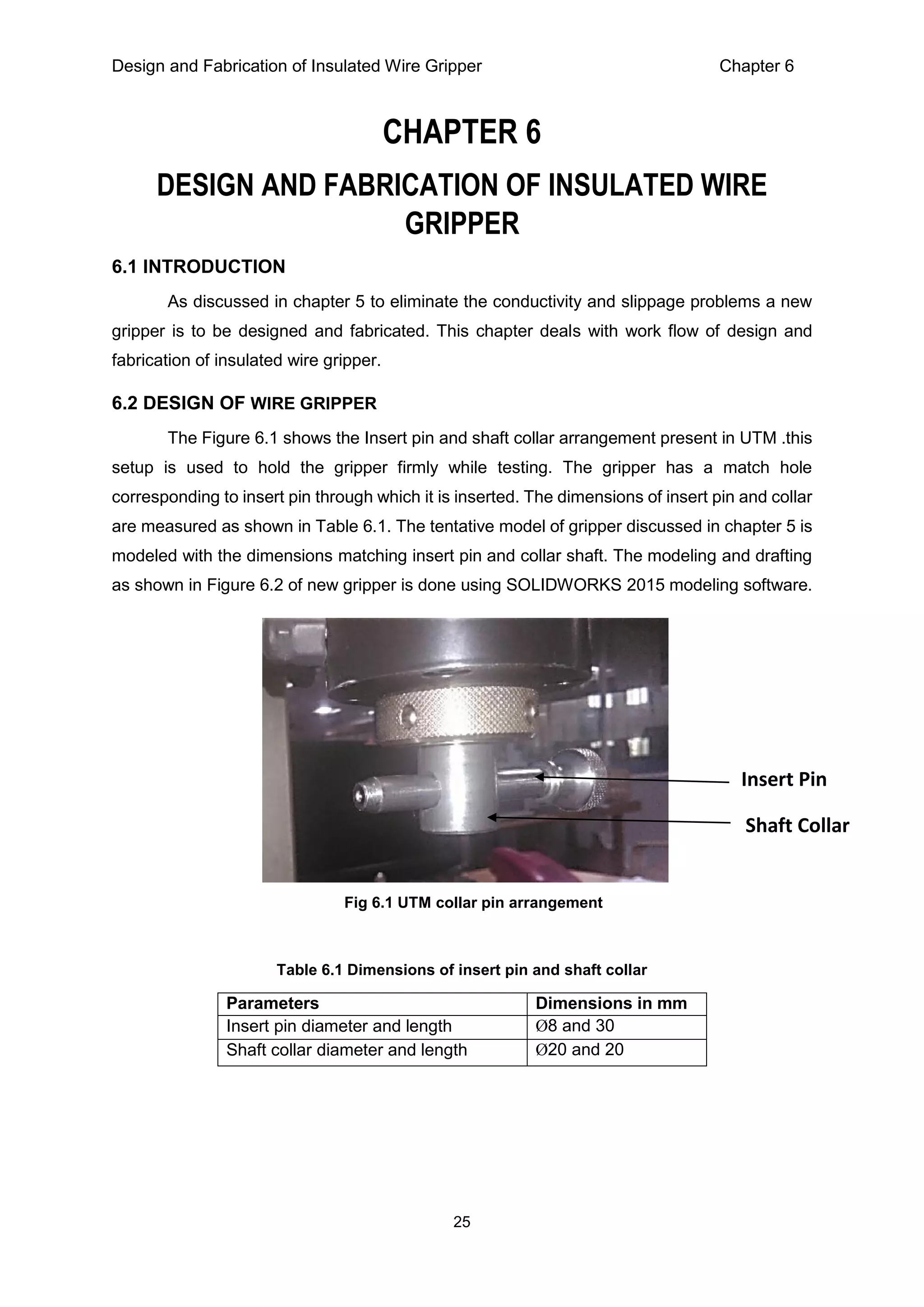

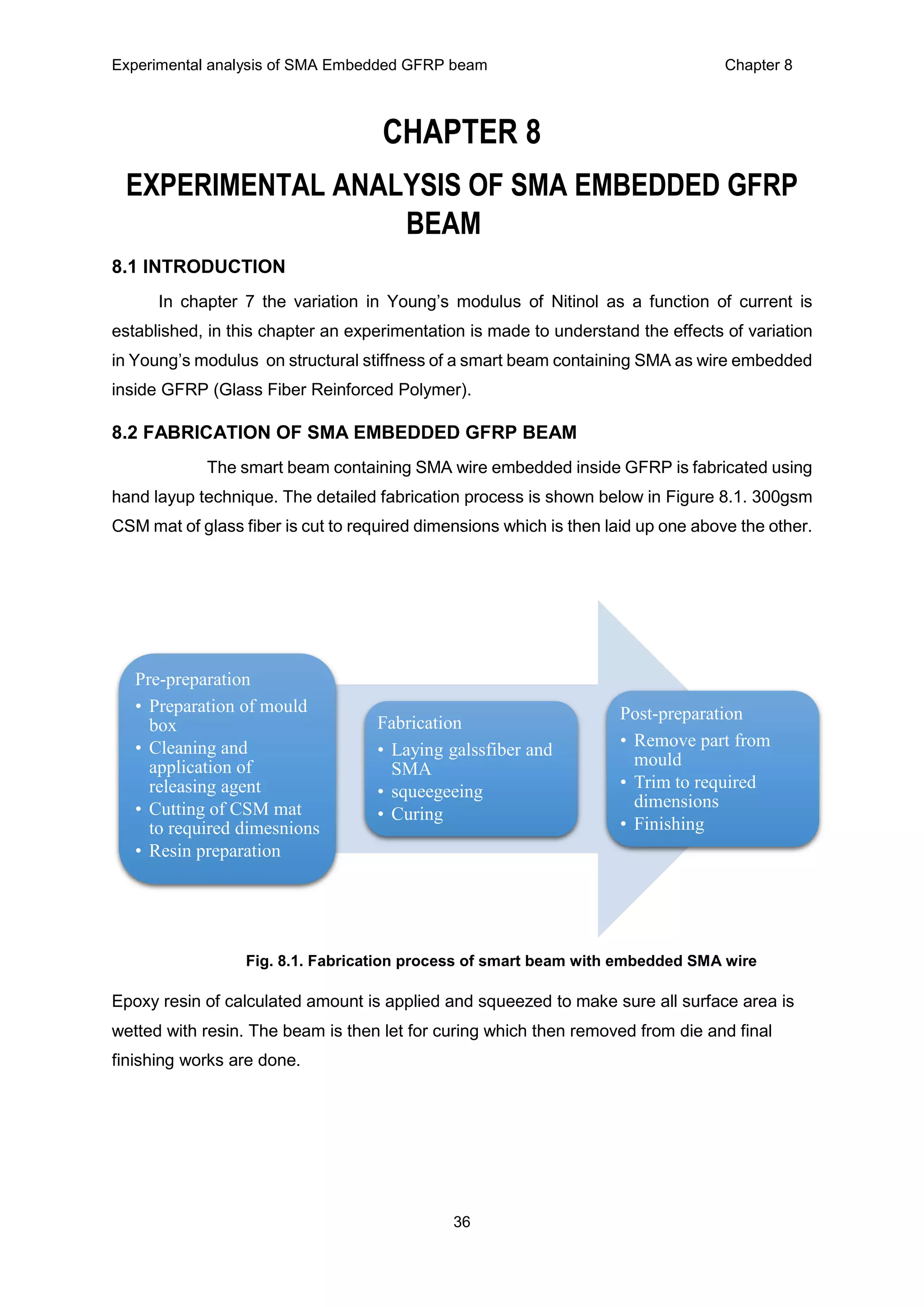

![Experimental analysis of SMA Embedded GFRP beam Chapter 8

40

The equivalent bending stiffness EI for smart beam with SMA wires, obtained according to the

classical composite-beam theory can be given as [10],

E(combined) = E(GFRP) (1- V(f)) + V(f) E(SMA)………………………………………………………………………....…………………………………….(3)

Where V(f) = volume of SMA / volume of GFRP

Substuting Equation (1) from chapter 7 in (3) the combined Young’s modulas is given as,

E(combined) = E(GFRP) (1- V(f)) + V(f)(-6.7699I2 + 31.077I + 17.738)……………………………………..…… (4)

Young’s Modulus change of GFRP as a function of temperature is shown in [13] is

incorperated as shown equation (5)

E(combined) = E(GFRP)( - 0.013 T(GFRP) + 1.8367) (1- V(f)) + V(f)(-6.7699I2 + 31.077I + 17.738)...................(5)

Where T(GFRP) = 4.9286 I2 – 5.0071 I + 30.964…………………………………………………………….. (6)

f(n) =

𝟏

𝟐𝝅

√

𝟑( − 𝟎.𝟏𝟑 𝑻(𝐺𝐹𝑅𝑃) + 𝟏𝟖.𝟑𝟔𝟕) (𝟏− 𝑽(𝒇)) + 𝑽(𝒇)(−𝟔.𝟕𝟔𝟗𝟗𝑰𝟐 + 𝟑𝟏.𝟎𝟕𝟕𝑰 + 𝟏𝟕.𝟕𝟑𝟖))𝑰𝒎

𝑳 𝟑 𝒎

………..………... (7)

Where, L, m, Im , vf corresponds to length of beam, mass of beam, moment of inertia of

beam, and volume fraction of SMA to GFRP respectively.

8.7 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

As the current increase the young’s Modulus of SMA increases and overall young’s

Modulus of smart beam increases. thus increases in natural frequency of smart beam is

observed till 1 ampere after which decrease in natural frequency is found. This is due to the

reason that the overall young’s Modulus of smart beam depends on both young’s Modulus of

GFRP and young’s Modulus of SMA. From the prior experimental study of SMA in chapter 7

shows that as current increases the young’s Modulus of SMA increases due to its solid phase

transformation. Once the current exceeding 1 ampere the overall temperature of beam

increases but young’s Modulus of GFRP decreases with increases in temperature.as shown

in Figure 9.1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ilovepdfmerged-180626180915/75/REPORT-ON-CHARACTERIZATION-OF-SHAPE-MEMORY-ALLOY-FOR-VIBRATION-ATTENUATION-IN-SMART-STRUCTURES-51-2048.jpg)

![Bibliography

47

11. Yuvaraja M, Senthilkumar M Procedia Engineering 64 ( 2013 ) 571 – 581,Comparative

study on Vibration Characteristics of a Flexible GFRP Composite beam using SMA

and PZT Actuators

12. Yuvaraja.M and Senthilkumar.M, ”Smart Material(SMA)-Based Actively Tuned

Dynamic Vibration Absorber for Vibration Control in Real Time Application”, Journal of

Engineering and Technology, Vol 3, Issue 2, Jul-Dec 2013.

13. Gangbing Songa, Bthu Kelly, Bnj N. Agrawal, ” Active Position Control of a Shape

Memory Alloy Wire Actuated Composite Beam”, Dept. of Mechanical Engineering, The

university of Akron, Akron, Ohio 44325 b Aeronautics and Astronautics Dept., Naval

Postgraduate School, Monterey, CA 93943.

14. Williams, K., G. Chiu, and R. Bernhard. "Adaptive-passive absorbers using shape-

memory alloys." Journal of Sound and Vibration 249.5 (2002): 835-848.

15. Santos, Filipe Pimentel Amarante dos. "Vibration control with shape-memory alloys in

civil engineering structures." (2011).

16. Esuff Khan and Sivakumar.M.Sirinivasan, “A New Approach to the Design of Helical

Shape Memory Alloy Spring Actuators”, Smart Materials Research Volume 2011,

Article ID 167195, 5 pages.

17. [17]. S.M.T. Hashemi, S.E. Khadem, “Modelling and analysis of the vibration behaviour

of shape memory alloy beam”, I.E.I Communication Industry Co.

18. Trochu F, Qian YY, “Nonlinear finite element simulation of superelastic shape memory

alloy parts”, Comput Struct 1997; 62(5): 799-810.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ilovepdfmerged-180626180915/75/REPORT-ON-CHARACTERIZATION-OF-SHAPE-MEMORY-ALLOY-FOR-VIBRATION-ATTENUATION-IN-SMART-STRUCTURES-58-2048.jpg)