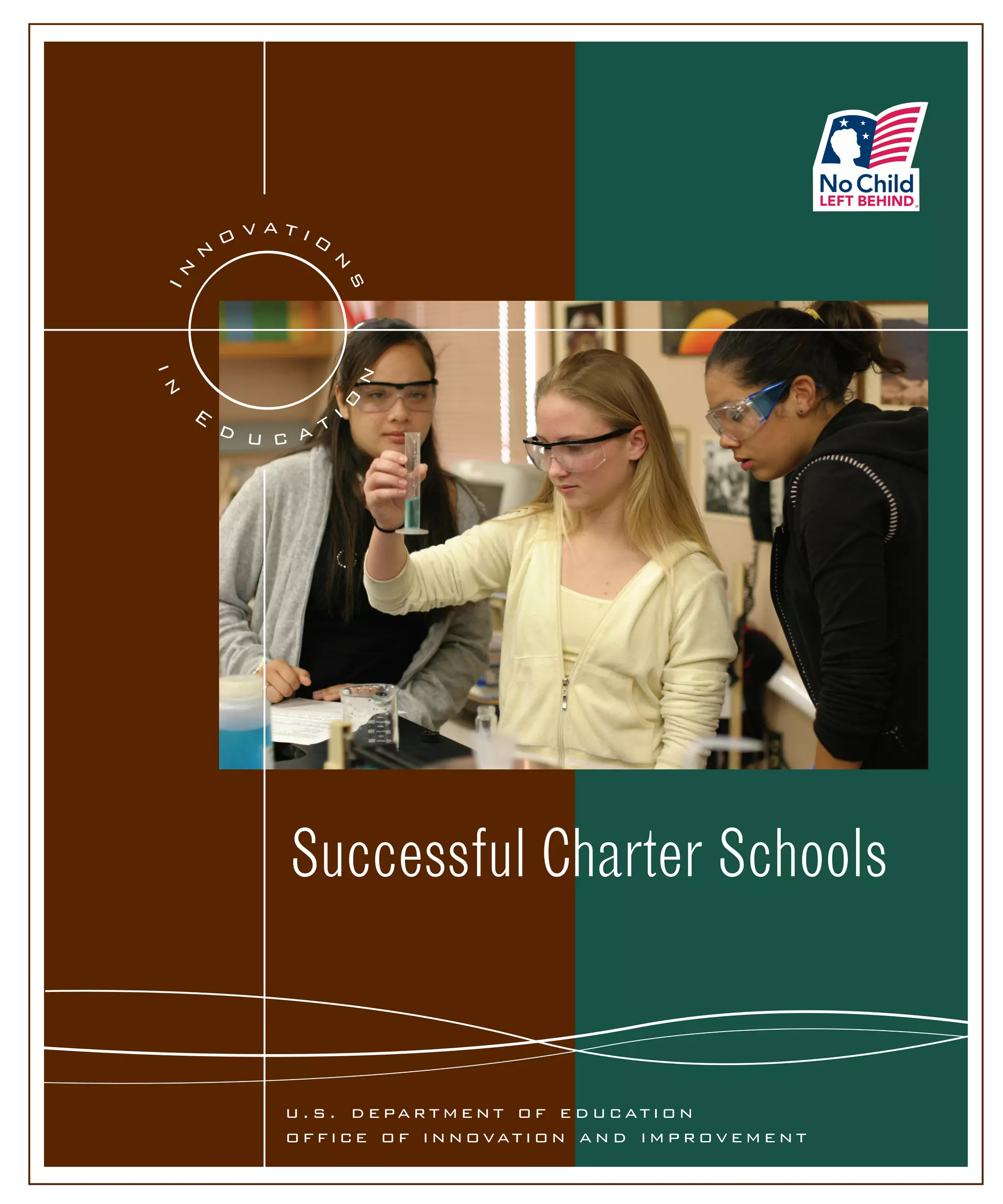

This document provides an overview of eight successful charter schools across the United States. It describes each school's location, grades served, enrollment numbers, student demographics, and distinctive programs. The schools were selected based on demonstrating three years of student achievement growth and meeting Adequate Yearly Progress goals. Site visits were conducted to observe classes, collect artifacts, and interview stakeholders. Key elements that contribute to the schools' success, such as their missions, innovations, learning communities, parent partnerships, and accountability, are examined. The profiles aim to showcase how charter school flexibility and autonomy, when paired with accountability, can transform public education.