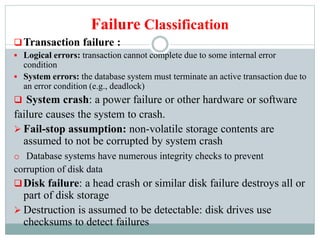

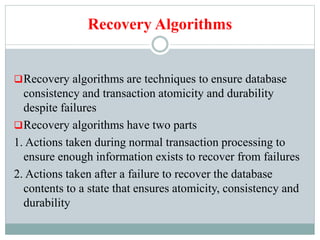

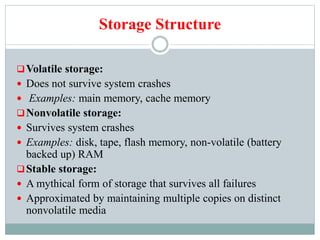

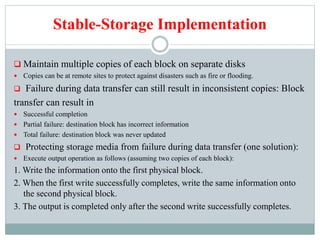

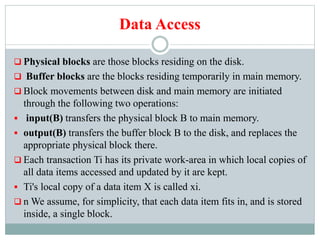

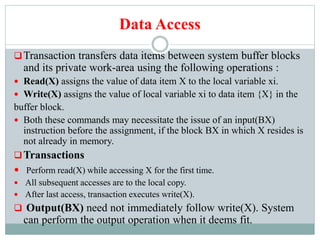

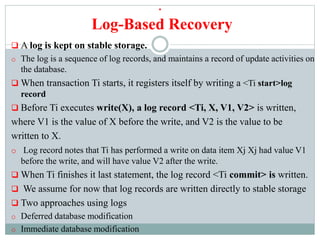

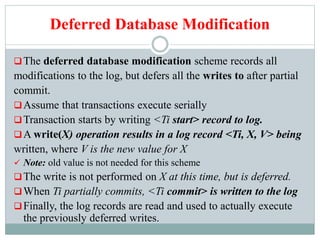

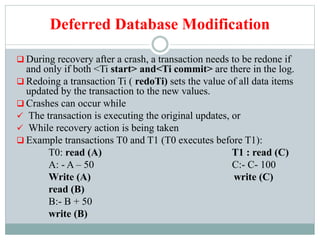

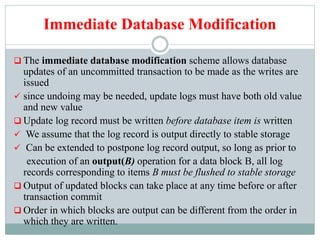

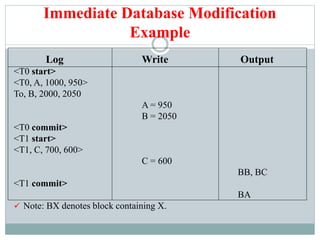

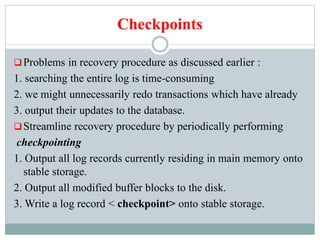

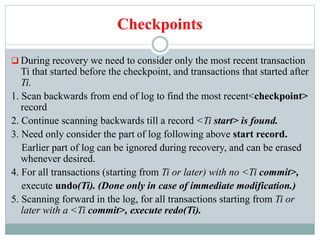

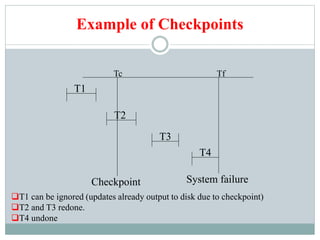

This document discusses recovery systems in relational database management. It covers failure classification, storage structures, log-based recovery using deferred and immediate database modification, shadow paging, checkpoints, and the ARIES recovery algorithm. Log-based recovery uses write-ahead logging and redo/undo operations to recover transactions and ensure atomicity and consistency after failures. Checkpoints improve recovery efficiency by limiting the log records that need to be processed.