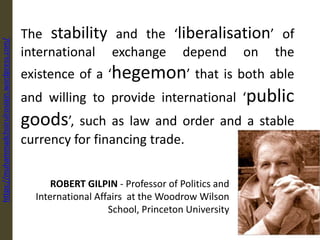

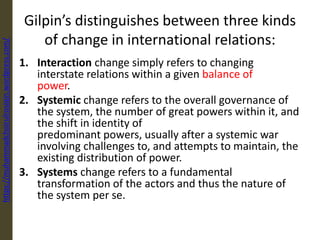

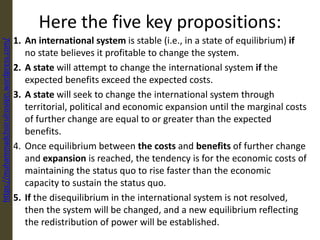

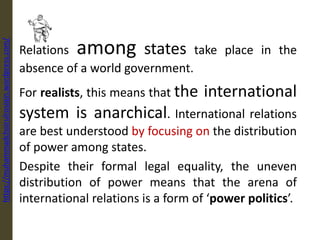

The document explores the concept of power politics within international relations, focusing on how states navigate an anarchical system where power distribution is uneven. It highlights the divergence in realist thought concerning balance of power and the dynamics influencing state behavior. Key thinkers such as Raymond Aron and Robert Gilpin are discussed, emphasizing frameworks for understanding systemic and interaction changes in international relations.

![https://muhammadchoirulrosiqin.wordpress.com/

Created by: Muhammad Choirul Rosiqin | International Relations Student of UMM

Book Source: Fifty Key Thinkers in International Relations [Martin Griffiths]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/realism-muhammadchoirulrosiqin-150216045726-conversion-gate02/75/REALISM-1-2048.jpg)

![RAYMOND ARON wrote in 1978

• [t]he rise of National Socialism . . . and the

revelation of politics in its dialogical essence forced

me to argue against myself, against my intimate

preferences; it inspired in me a sort of revolt against the

instruction I had received at the university, against the

spirituality of philosophers, and against the tendency of

certain sociologists to misconstrue the impact of regimes

with the pretext of focusing on permanent realities.

https://muhammadchoirulrosiqin.wordpress.com/](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/realism-muhammadchoirulrosiqin-150216045726-conversion-gate02/85/REALISM-7-320.jpg)