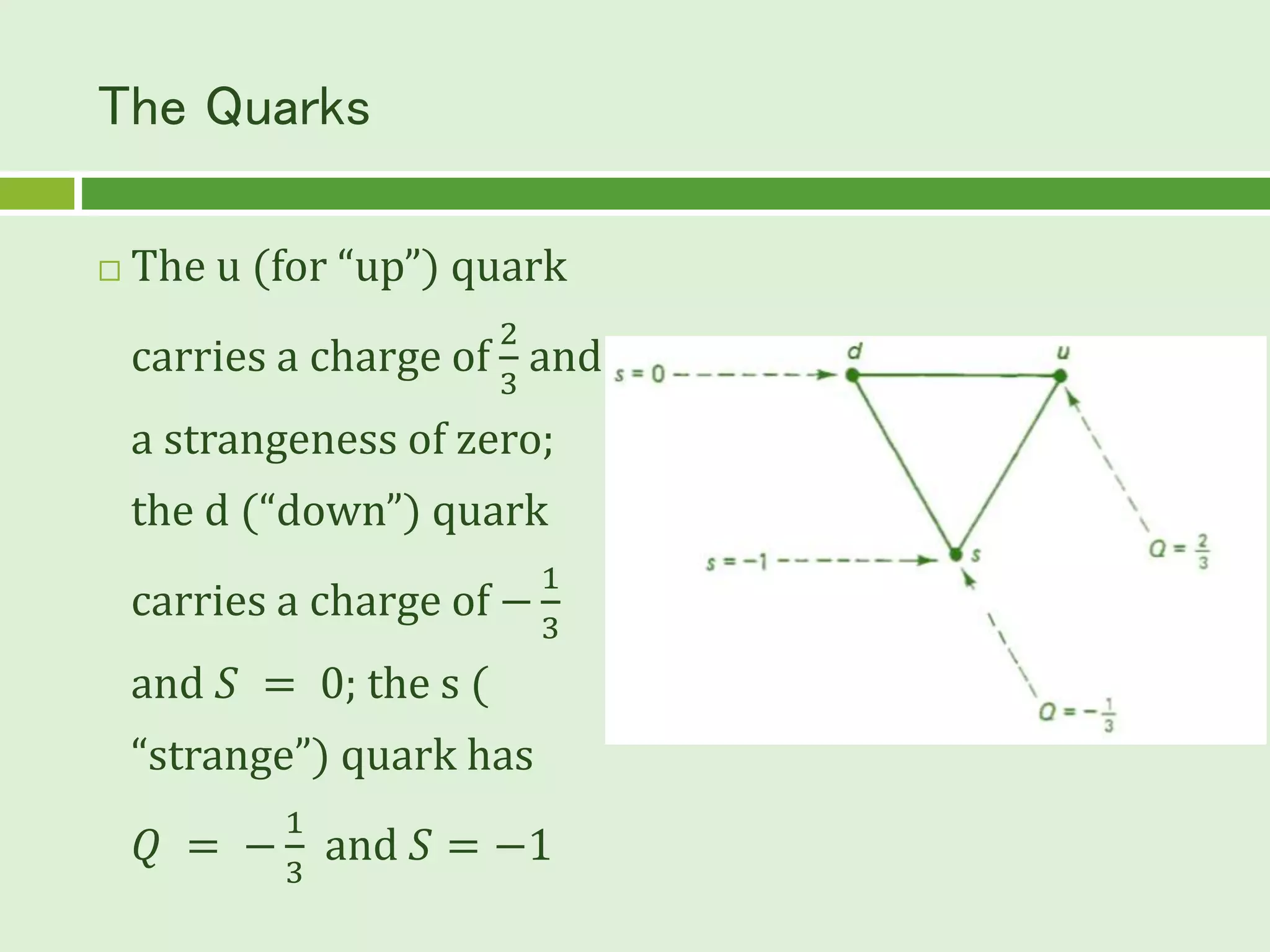

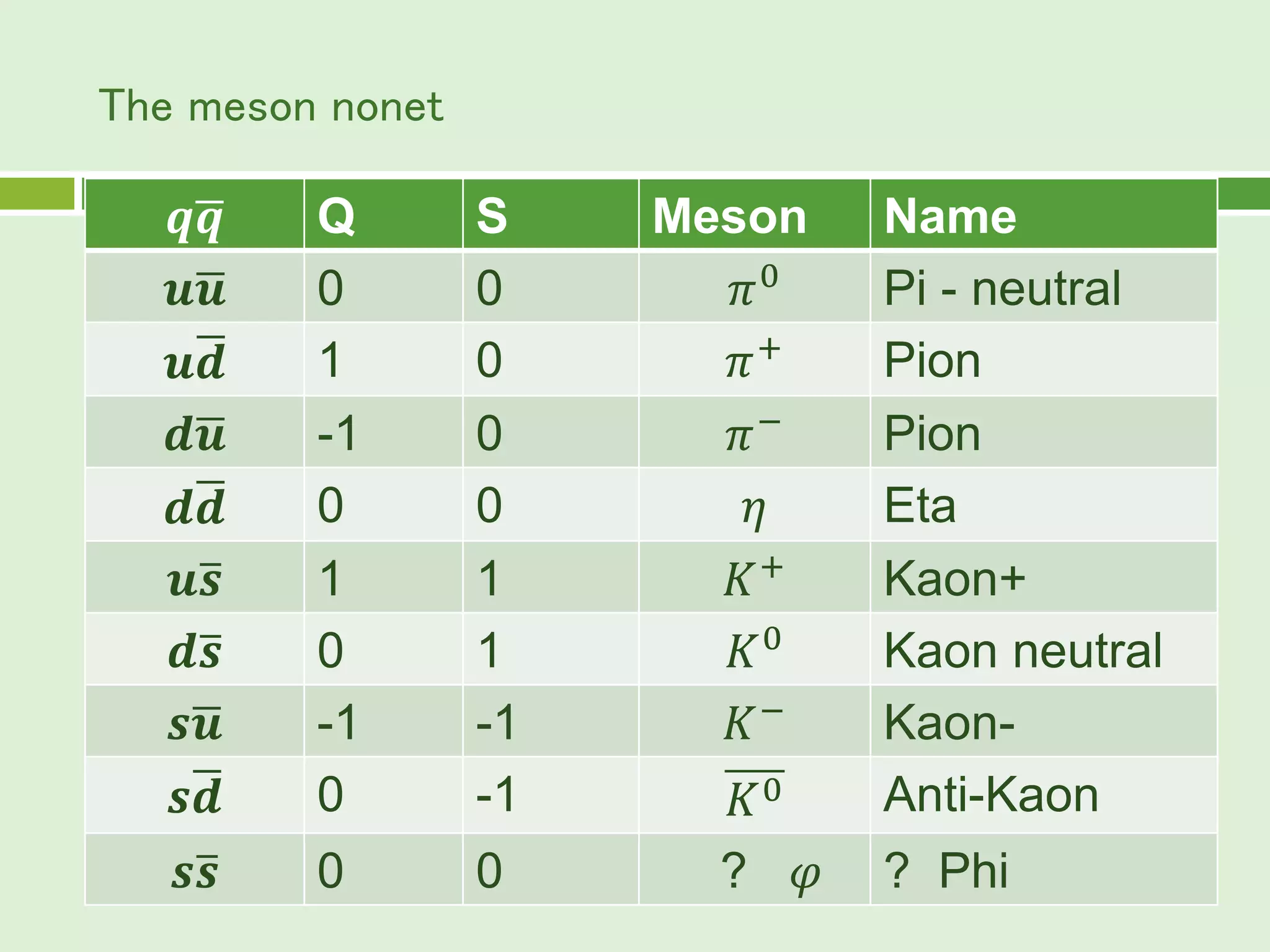

The document summarizes the quark model proposed in 1964 to describe the internal structure of hadrons such as protons and neutrons. It states that all hadrons are composed of more fundamental particles called quarks, which come in three flavors: up, down, and strange. The model was later expanded to incorporate three colors and additional quark flavors as more particles were discovered. The quark model provided explanations for experimental findings and made accurate predictions that were later verified, gaining broad acceptance.