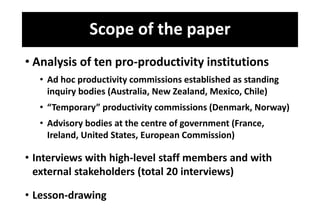

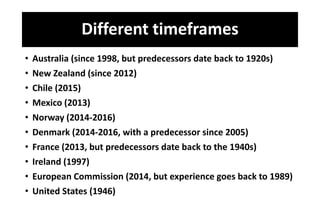

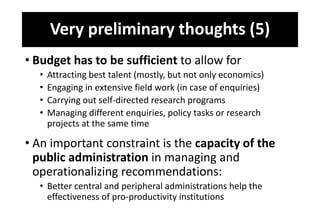

This document analyzes ten pro-productivity institutions from different countries. It discusses some very preliminary thoughts based on interviews conducted so far. Key points include: there is no one-size-fits-all model and institutions need to adapt to national contexts. Political commitment is important to establish and maintain these institutions. Independence, transparency, and producing high quality work are important for legitimacy. The degree of institutionalization and ability to engage in evidence-based policymaking affects how effective these institutions can be. Sufficient funding is also important to attract talent and carry out various functions.