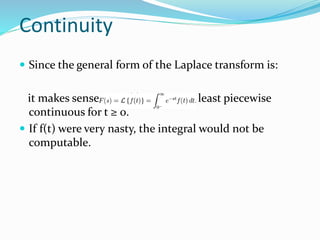

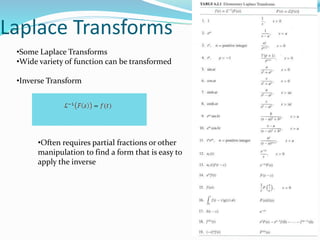

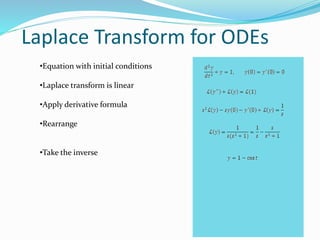

Pierre-Simon Laplace made important contributions to mathematics, astronomy, physics, and statistics. He began working in calculus, which led to developing the Laplace transform. The Laplace transform is a linear operator that switches a function of time to a function of a complex variable, allowing differential equations to be solved more easily. It has various restrictions on the original function for the transform to be applied. The transform is widely used to solve ordinary and partial differential equations and has applications in areas like semiconductor mobility and modeling physical systems.