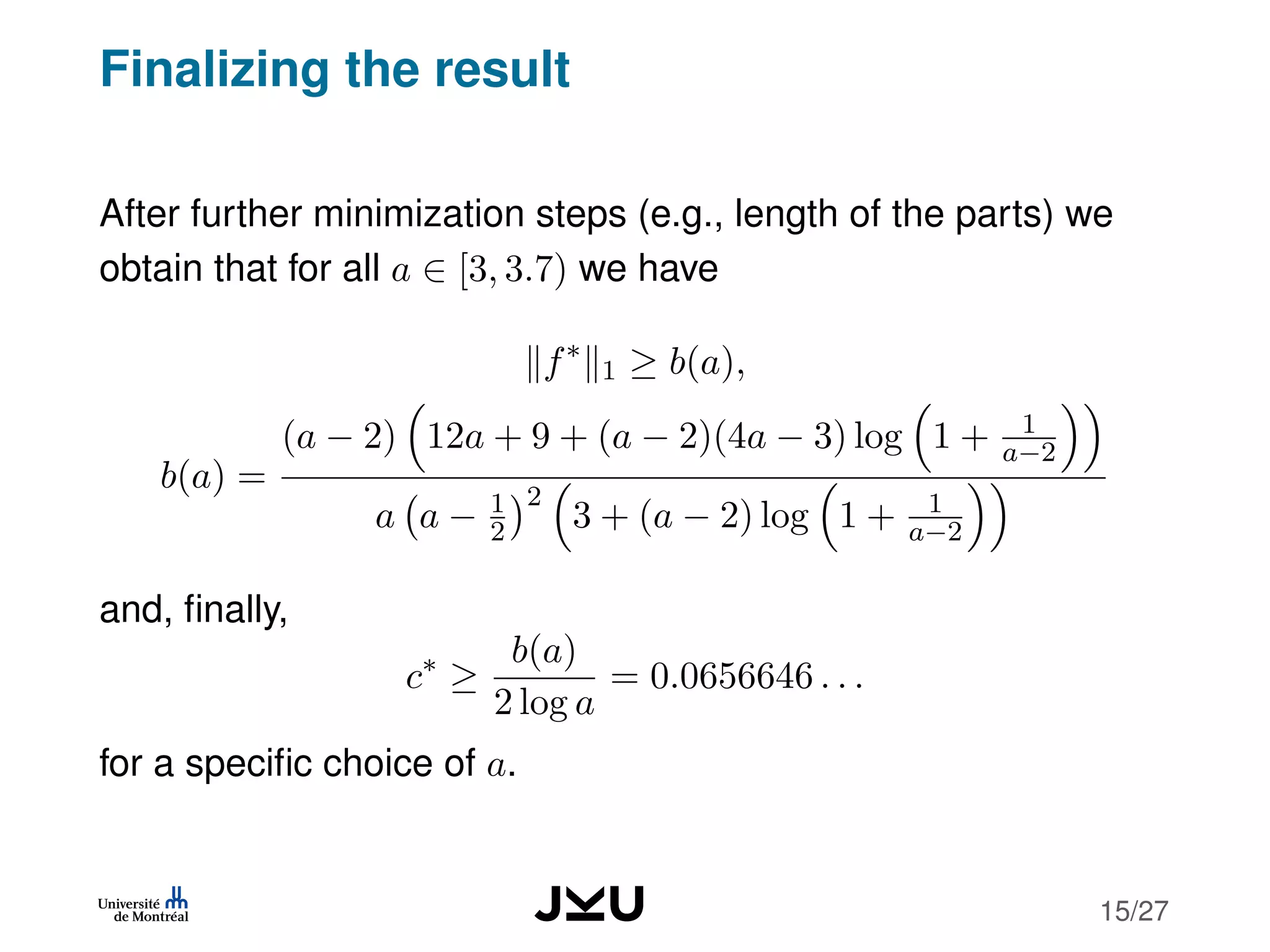

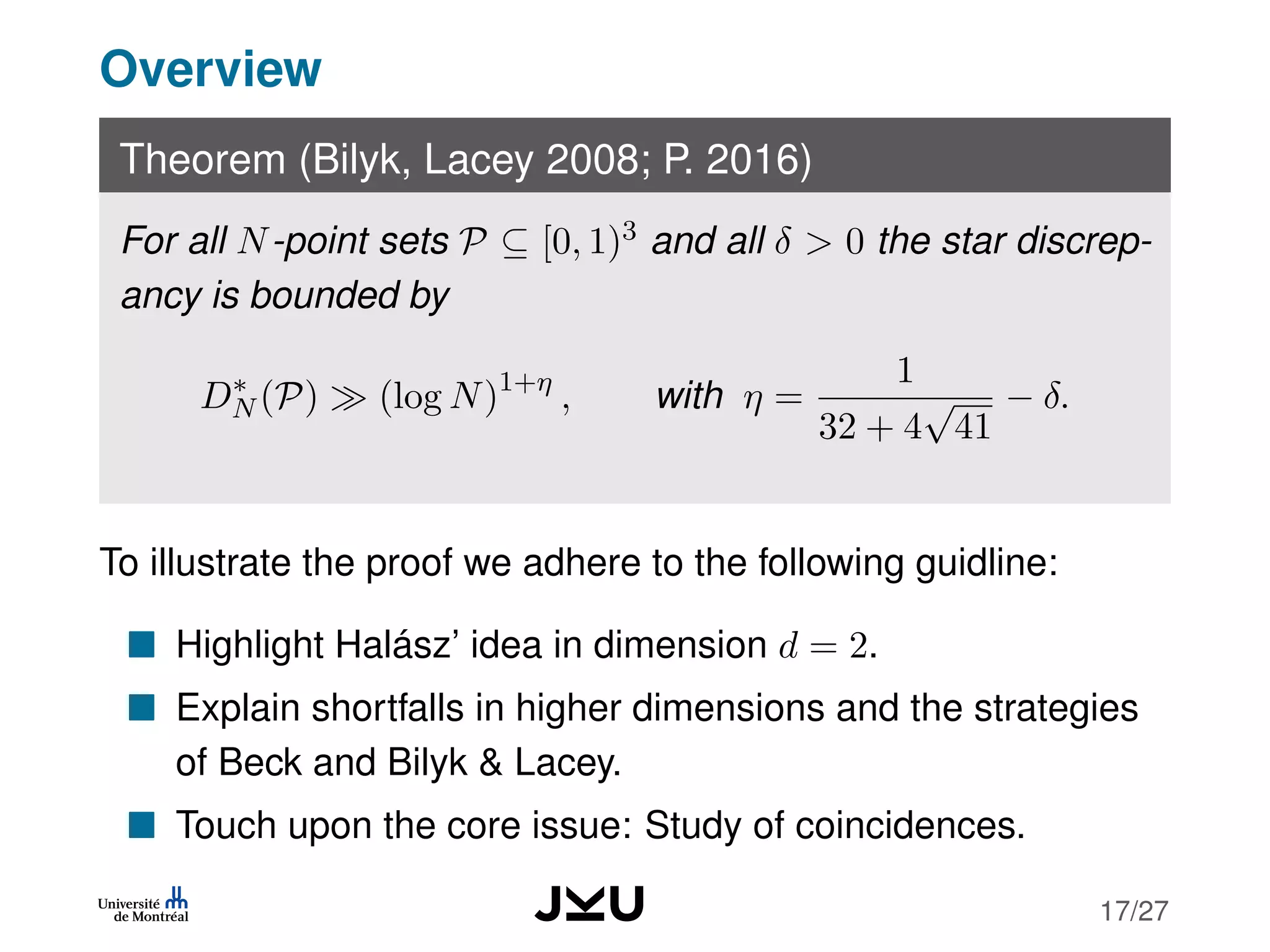

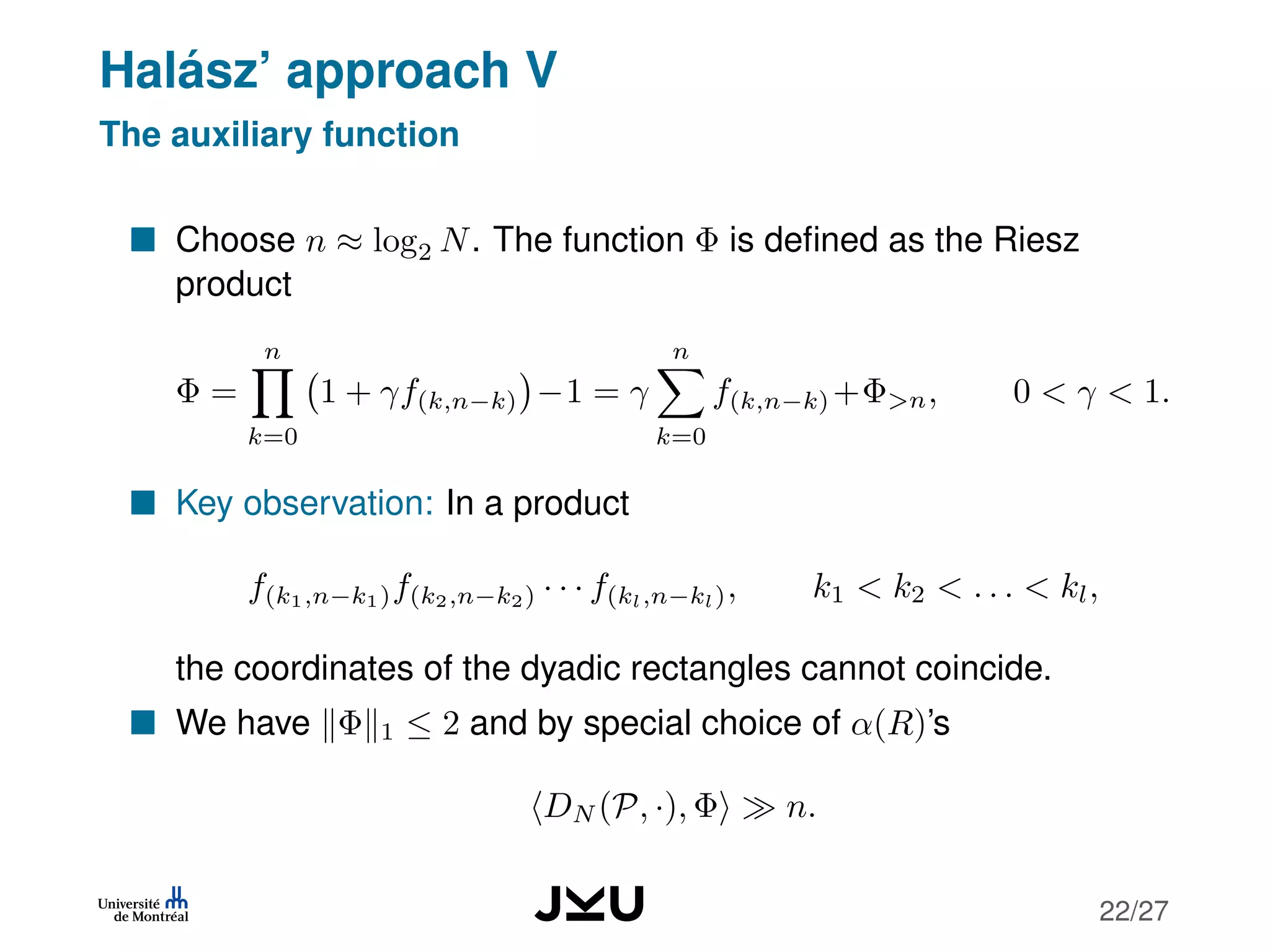

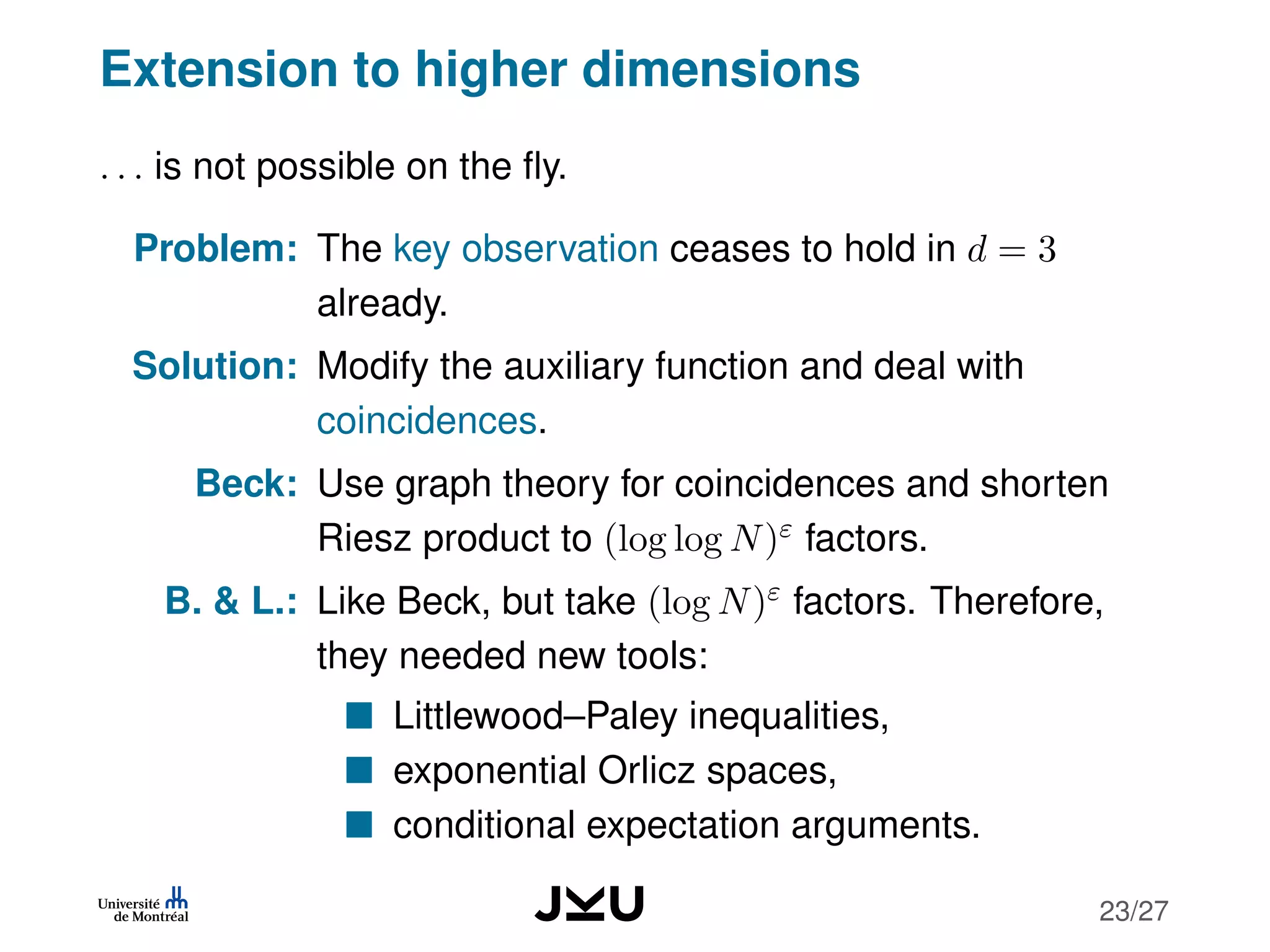

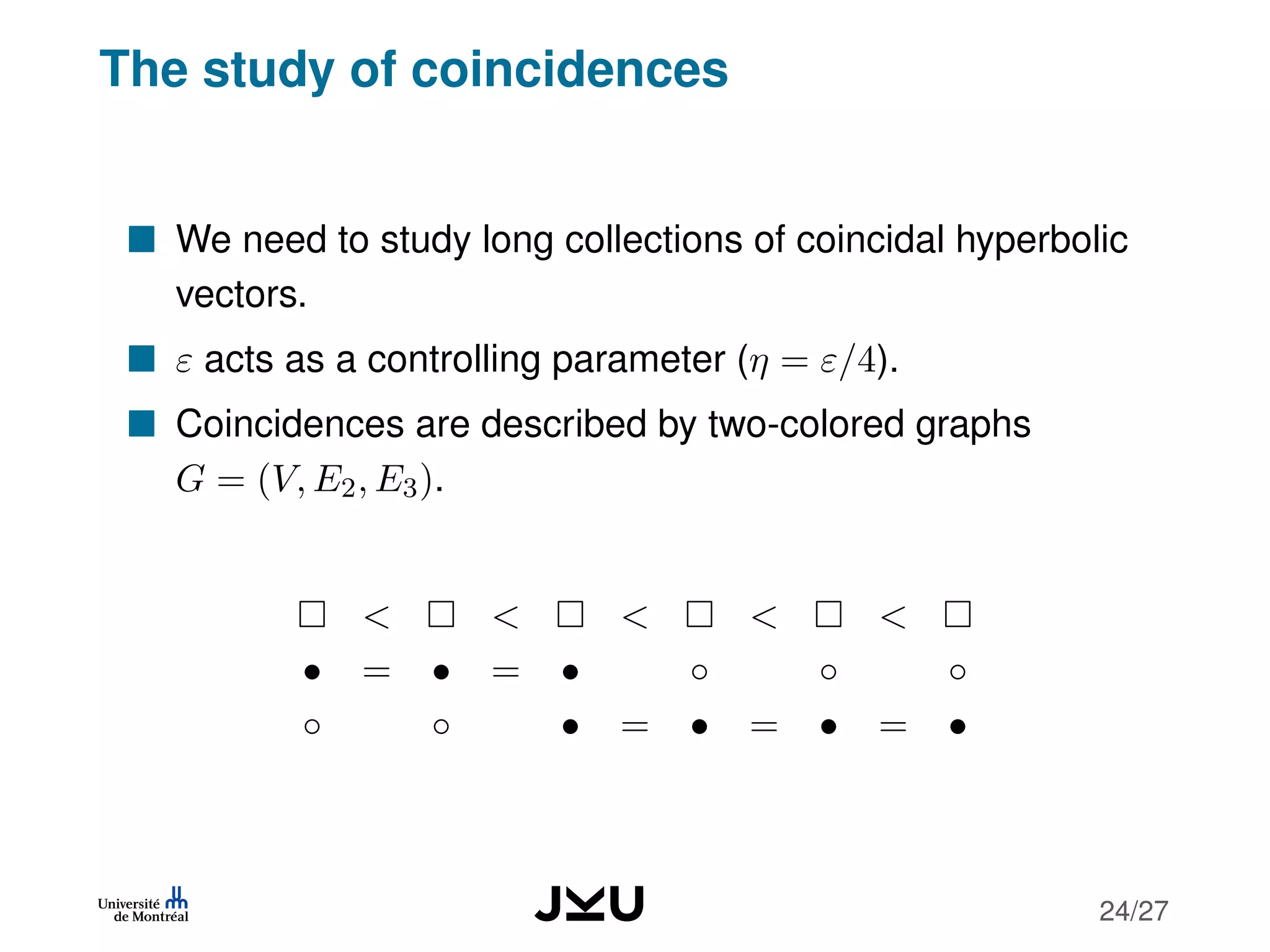

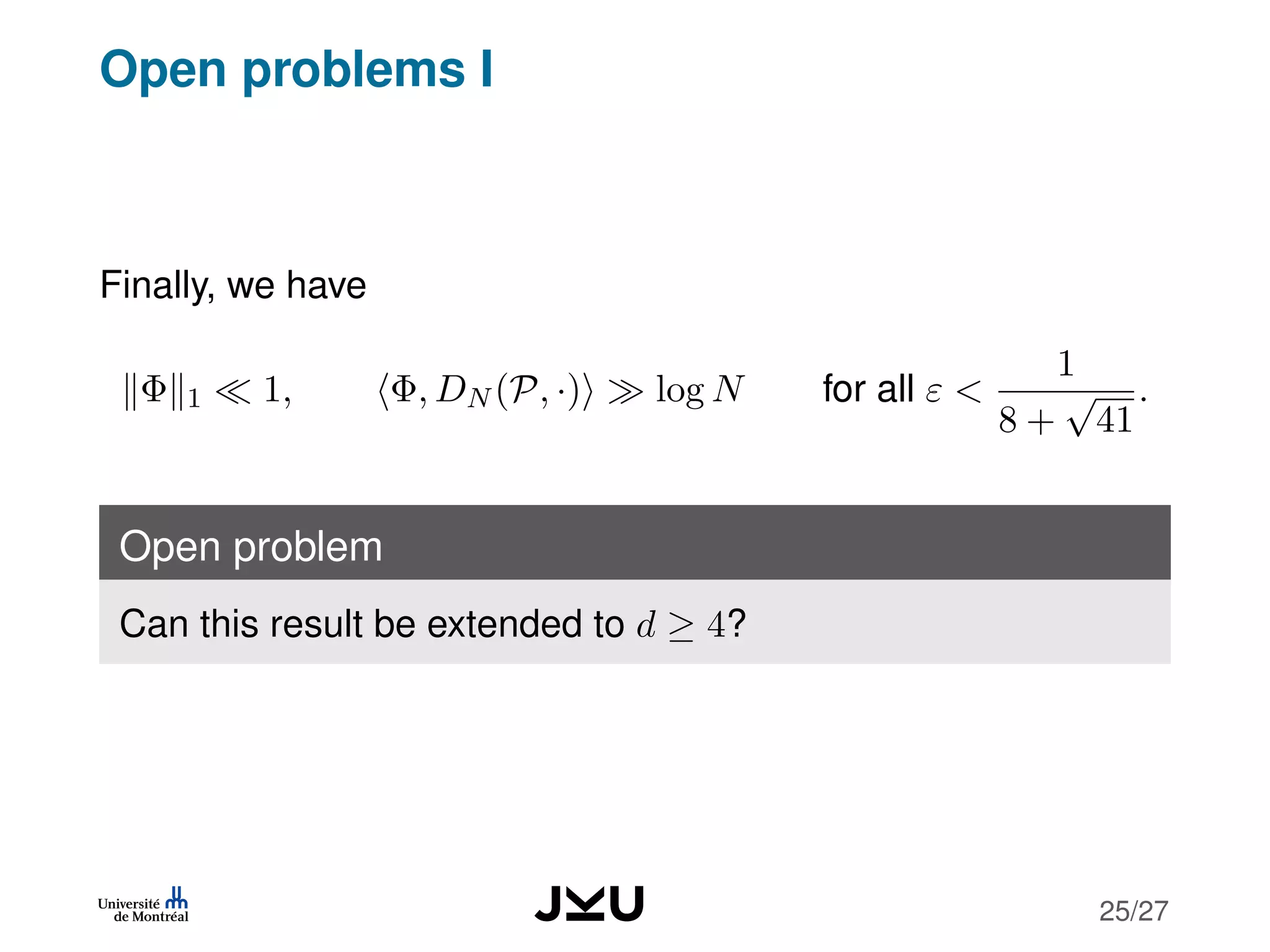

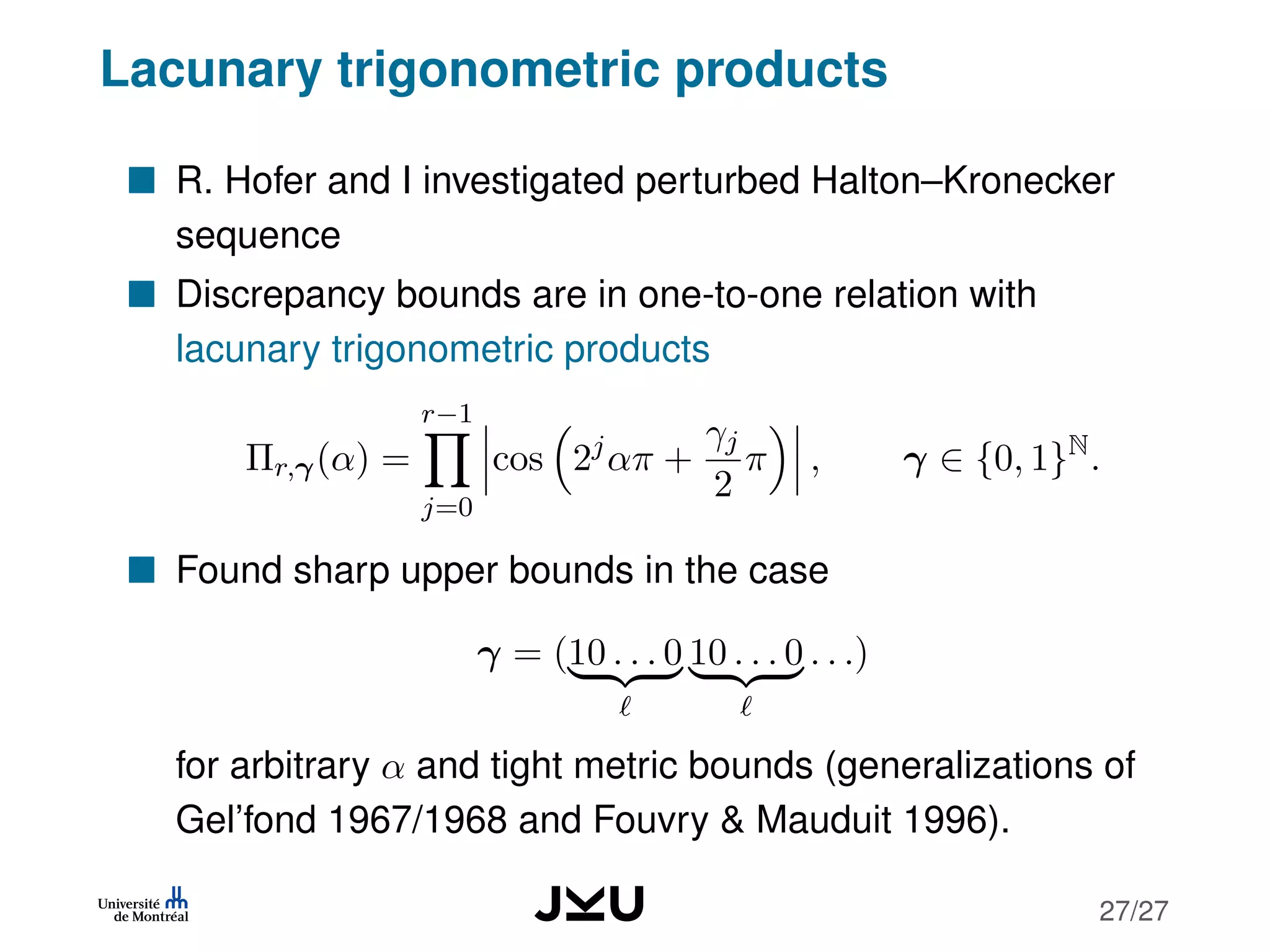

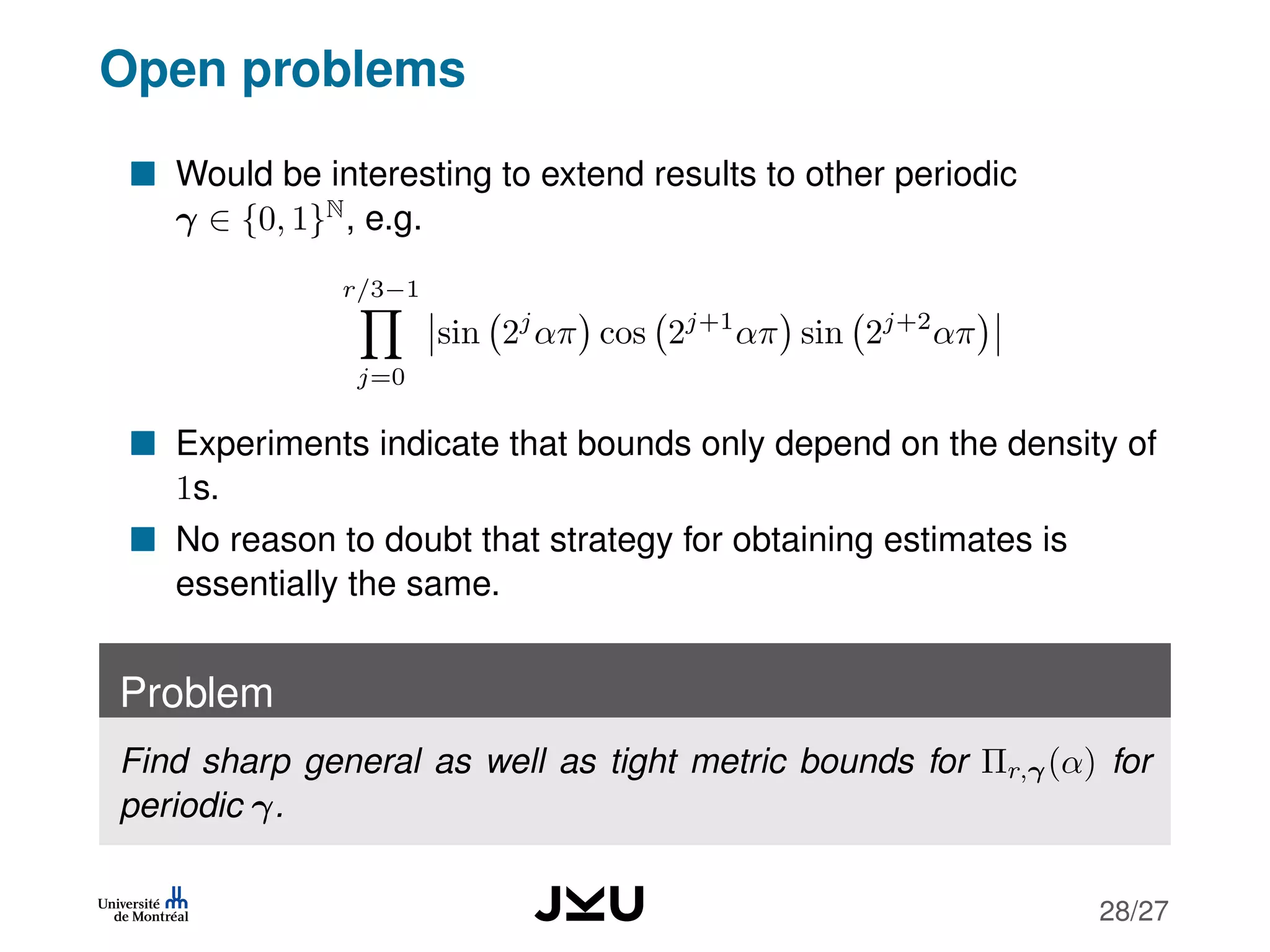

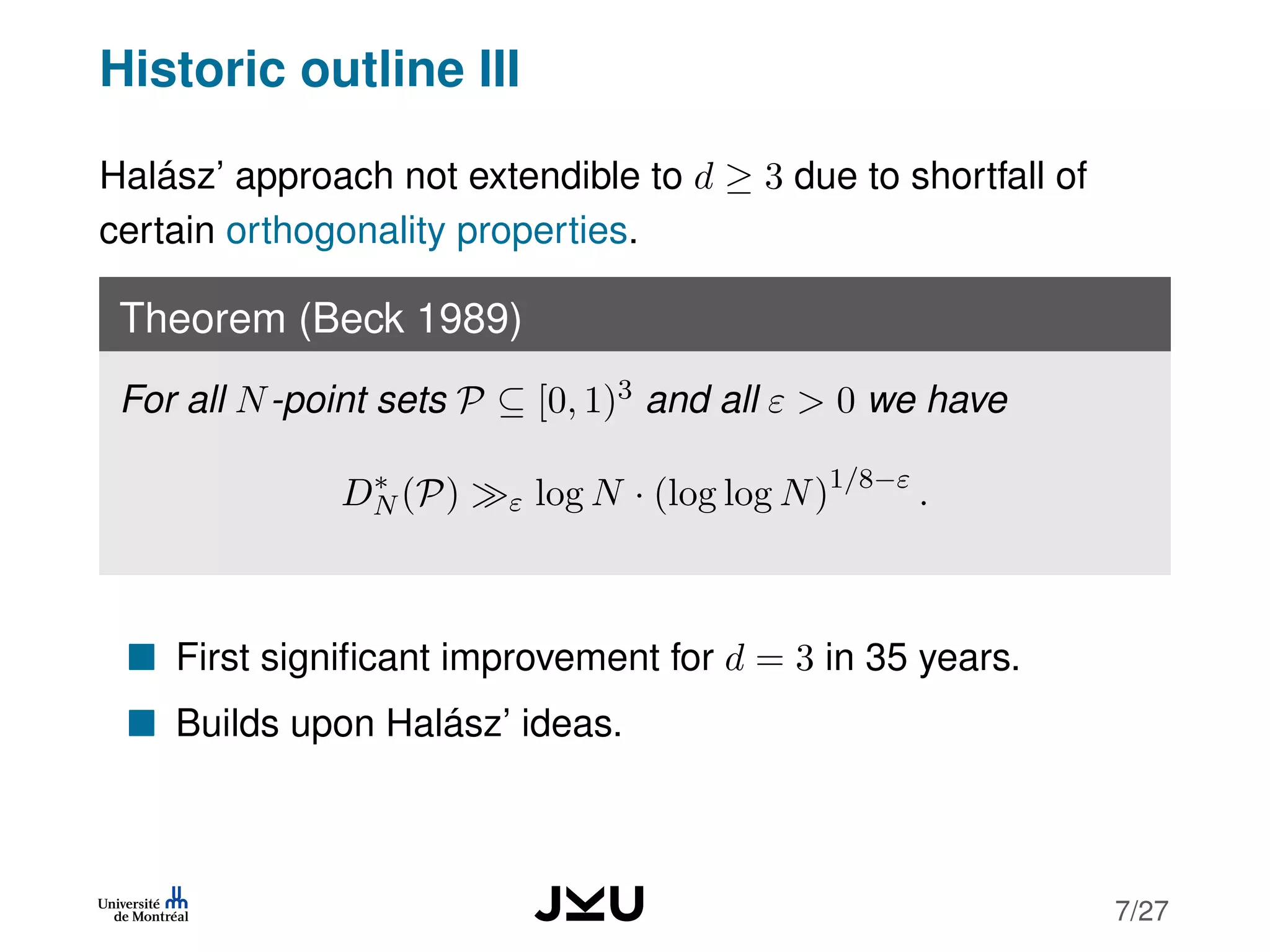

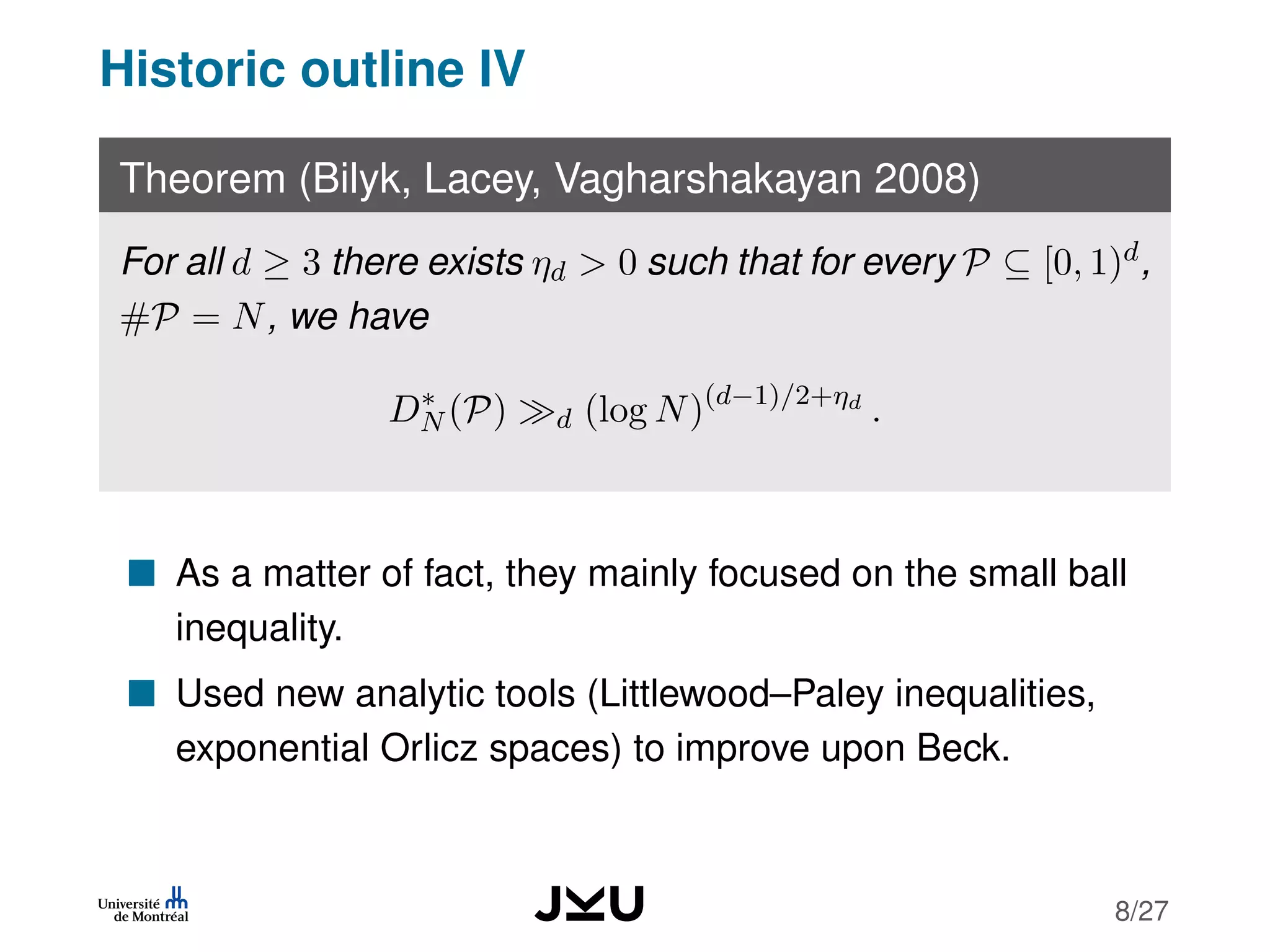

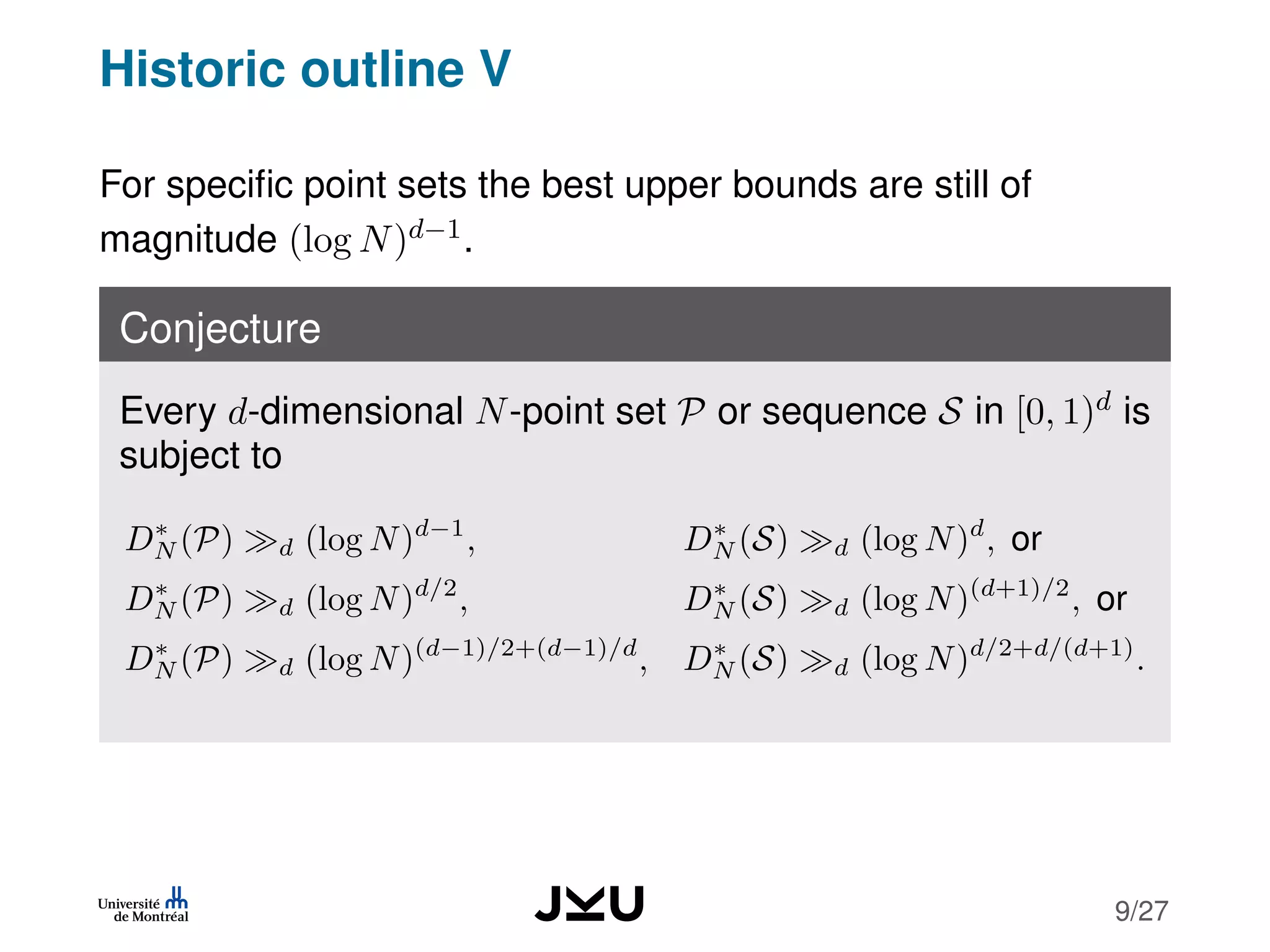

The document discusses lower bounds for the star discrepancy of point sets and sequences, presenting both known results and conjectures on the corresponding discrepancies based on collaborations with Gerhard Larcher and Roswitha Hofer. It outlines the historical context of discrepancy theory, links it to quasi-Monte Carlo integration, and provides theorems demonstrating the growth of star discrepancy with respect to various dimensions. The document also raises open problems regarding the extension of findings to higher dimensions and the connection with lacunary trigonometric products.

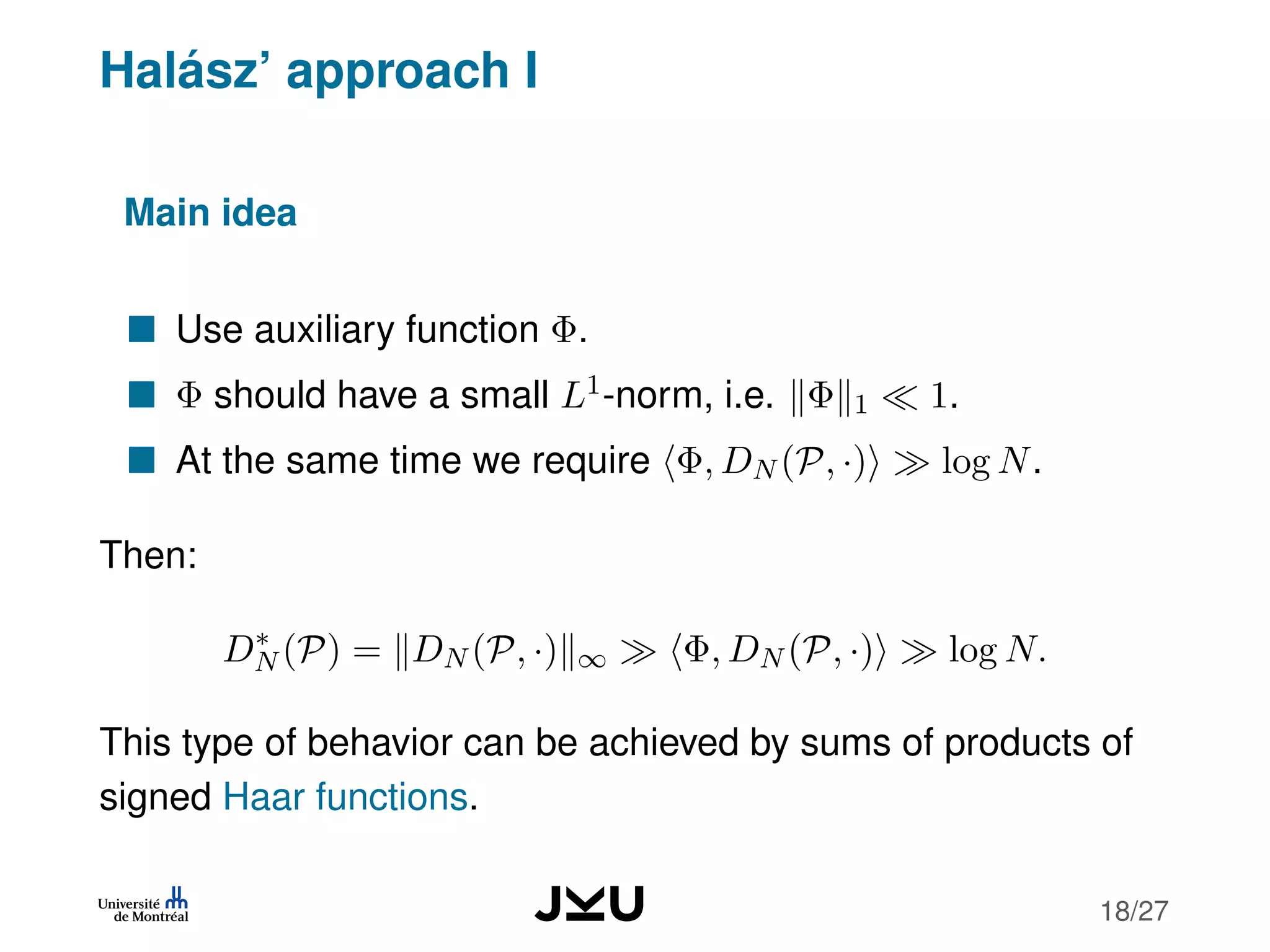

![Important connections I

Quasi-Monte Carlo (QMC) integration

Quadrature rules with nodes P = {p1, . . . , pN } ⊆ [0, 1)d

Id(f) =

[0,1)d

f(x) dx ≈

1

N

N

k=1

f(pk) =: QN,P (f).

Koksma–Hlawka inequality: For f : [0, 1]d

→ R with bounded

variation we have,

|Id(f) − QN,P (f)| ≤ cf

D∗

N (P)

N

, cf > 0.

D∗

N (P) determines the quality of this approximation.

Specific upper bounds

2/27](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/puchhammersamsitalk-170901163539/75/Program-on-Quasi-Monte-Carlo-and-High-Dimensional-Sampling-Methods-for-Applied-Mathematics-Opening-Workshop-Lower-Bounds-for-the-Discrepancy-of-Point-Sets-and-Sequences-Florian-Puchhammer-Aug-31-2017-4-2048.jpg)

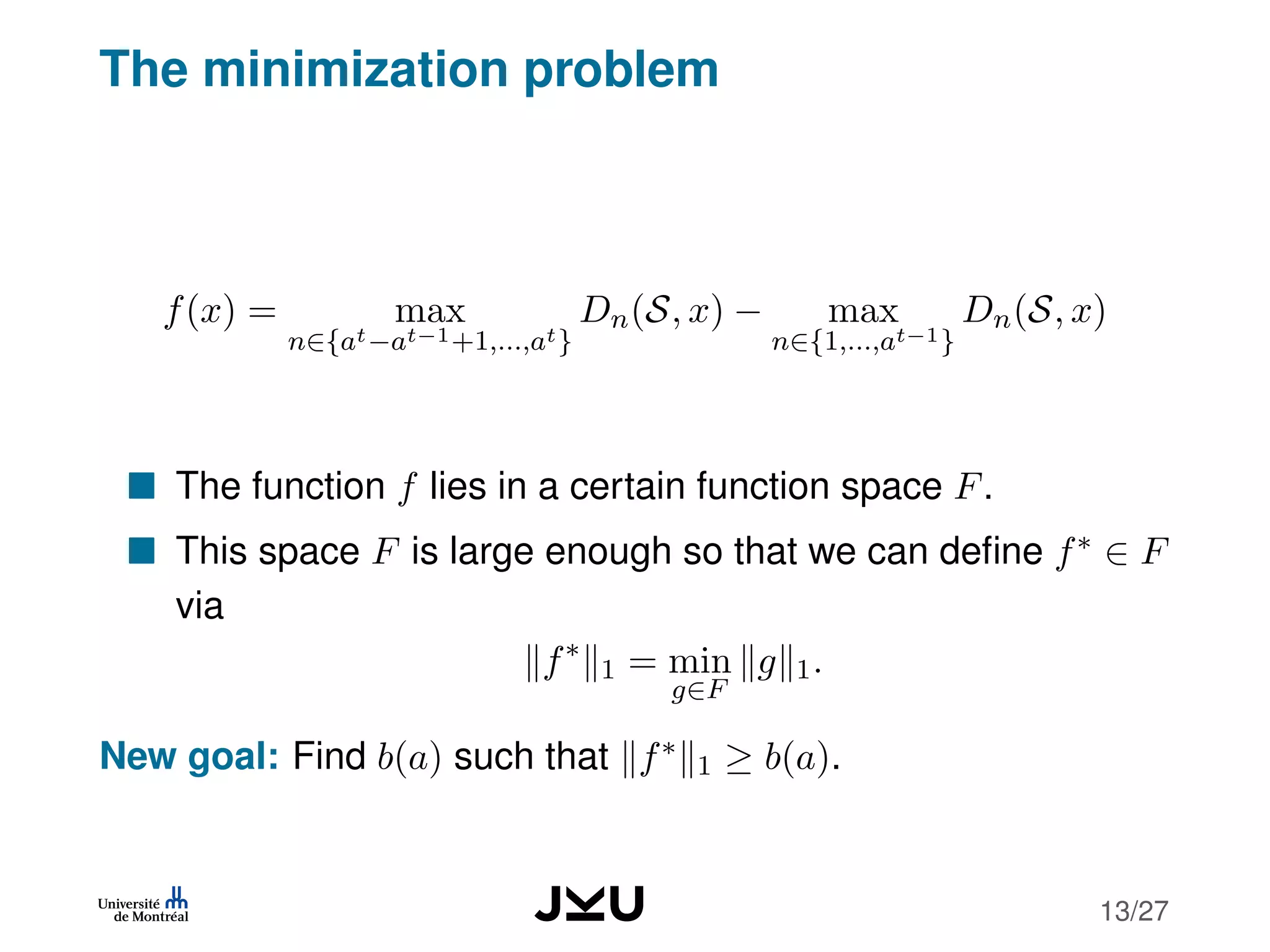

![Estimation of the solution

Lemma

The function f∗ comprises exactly at−1 parts Q0, at−1(a − 2)

parts Q1, and parts Q

(n)

2 , 1 ≤ n < at−1.

Each such part is characterized by an interval [α, β] with

f∗(α) = f∗(β) = 0, one discontinuity at some point γ, and the

behavior of the slope of f∗ on [α, β].

14/27](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/puchhammersamsitalk-170901163539/75/Program-on-Quasi-Monte-Carlo-and-High-Dimensional-Sampling-Methods-for-Applied-Mathematics-Opening-Workshop-Lower-Bounds-for-the-Discrepancy-of-Point-Sets-and-Sequences-Florian-Puchhammer-Aug-31-2017-18-2048.jpg)