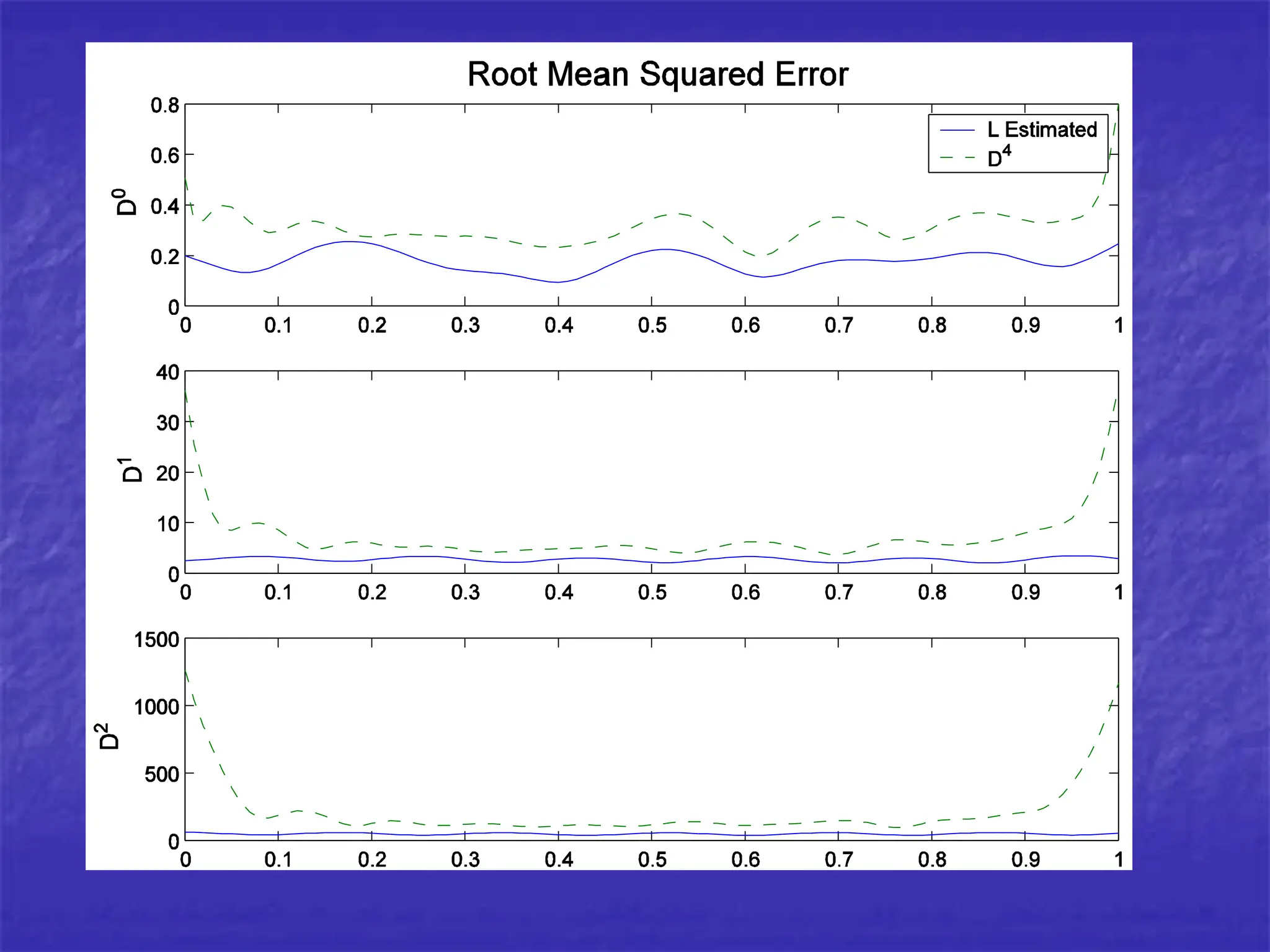

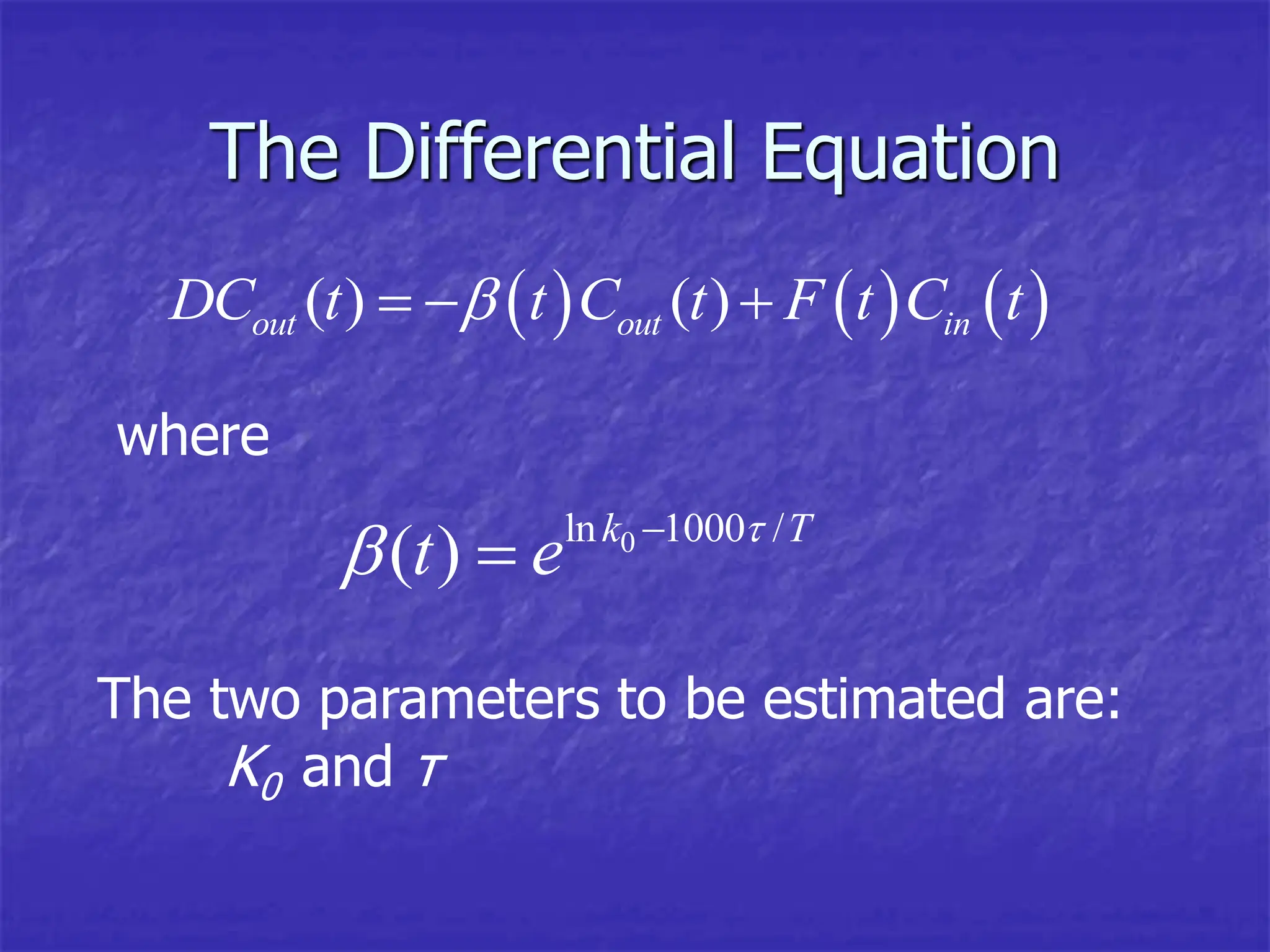

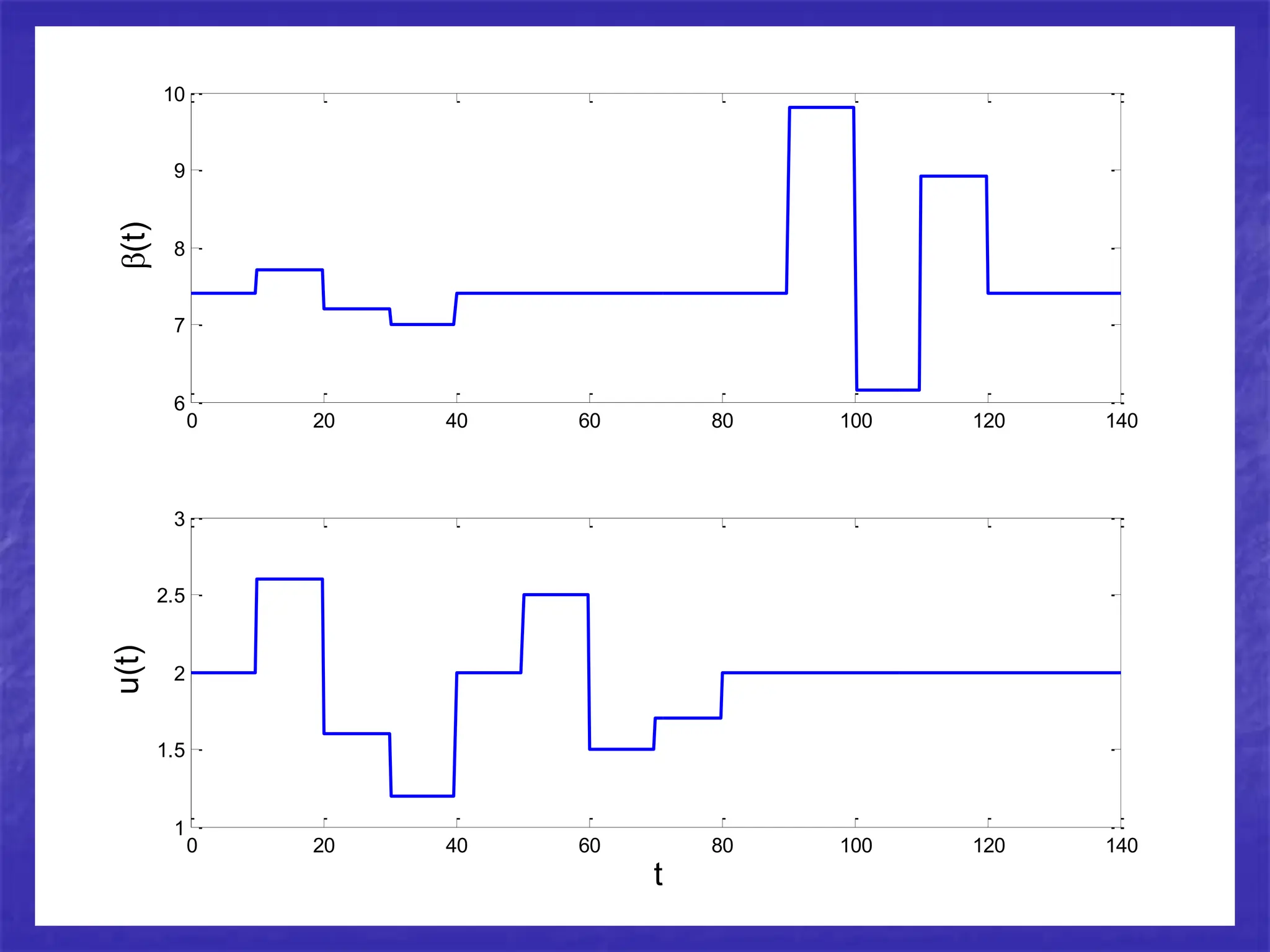

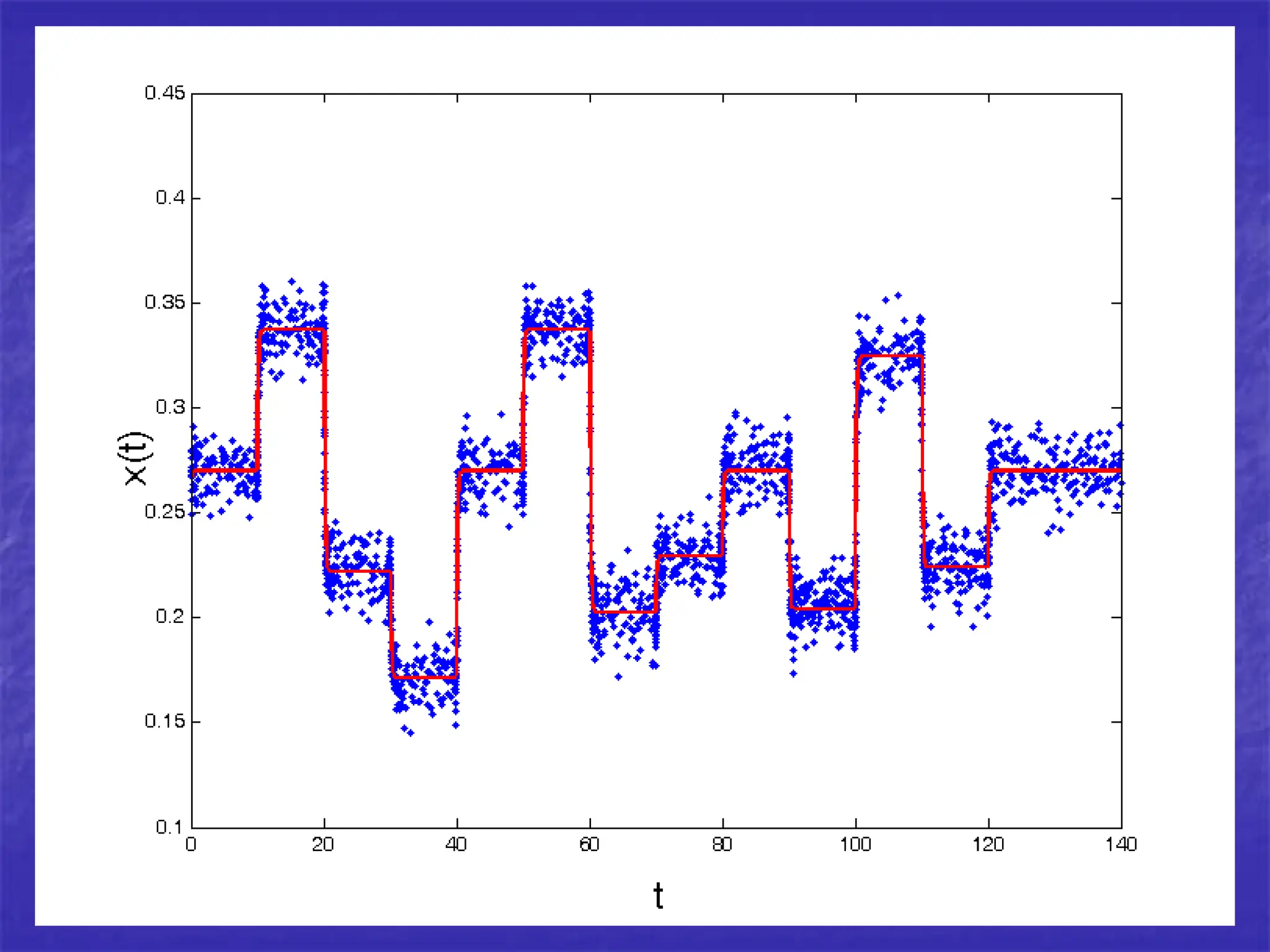

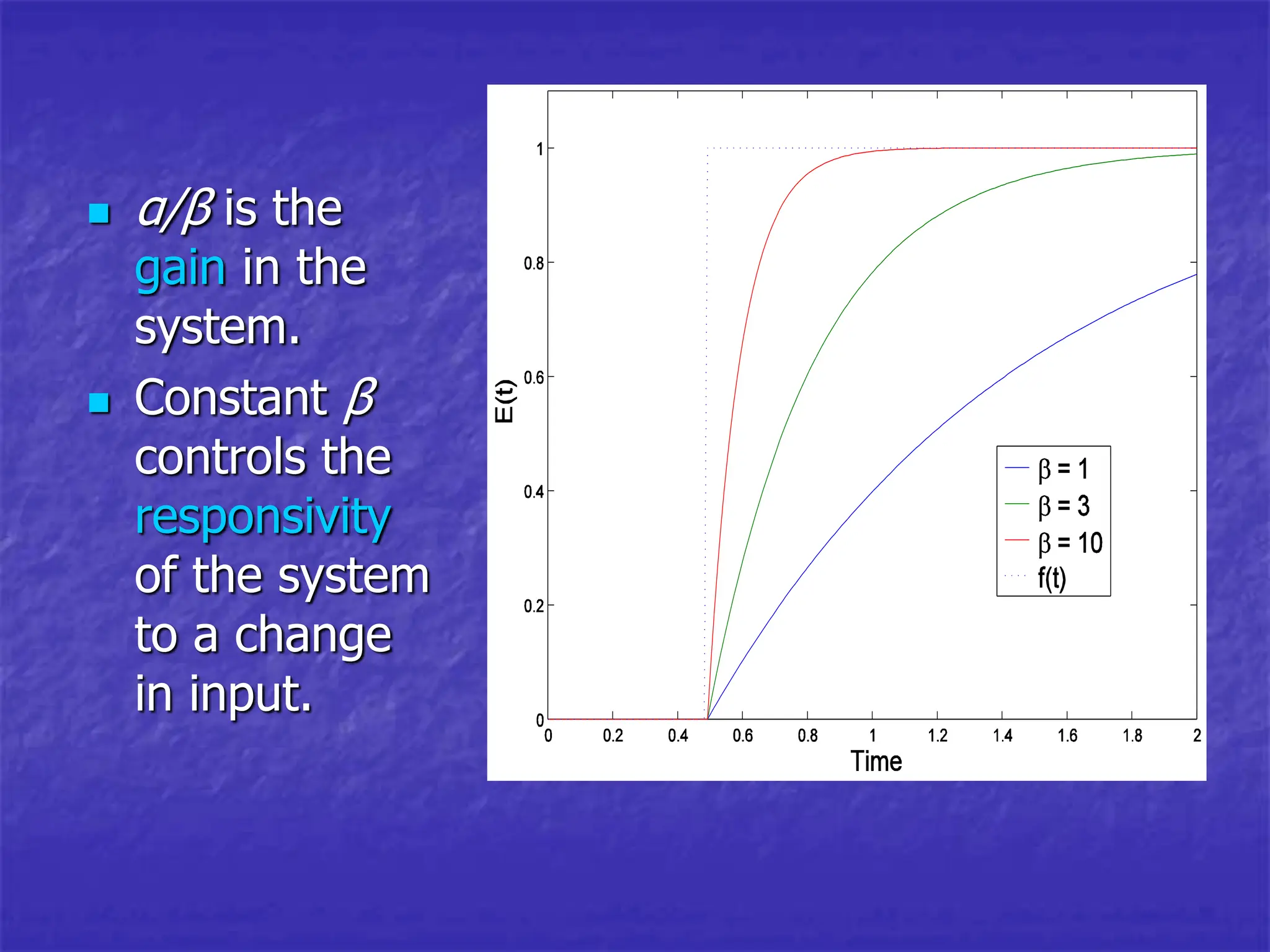

Differential equations can be powerful tools for modeling data. New methods allow estimating differential equations directly from data. As an example, the author estimates a differential equation model from simulated data from a chemical reactor. The estimated parameters are close to the true values, demonstrating the method works well on simulated data.

![From Data to Differential

Equations

Jim Ramsay

McGill University

( ) [ ( ), ]

Dx t f x t t

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fromdatatodifferentialequations-231008095055-02399aac/75/from_data_to_differential_equations-ppt-1-2048.jpg)

![In this simple case, an analytic solution is

possible:

0

( ) ( )[ (0) [ ( )/ ( )] ]

t

x t h t x s u s h s ds

However, in most situations involving

DIFE’s it is necessary to use numerical

methods to find the solution.

where

0

( )

( )

t

s ds

h t e

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fromdatatodifferentialequations-231008095055-02399aac/75/from_data_to_differential_equations-ppt-15-2048.jpg)

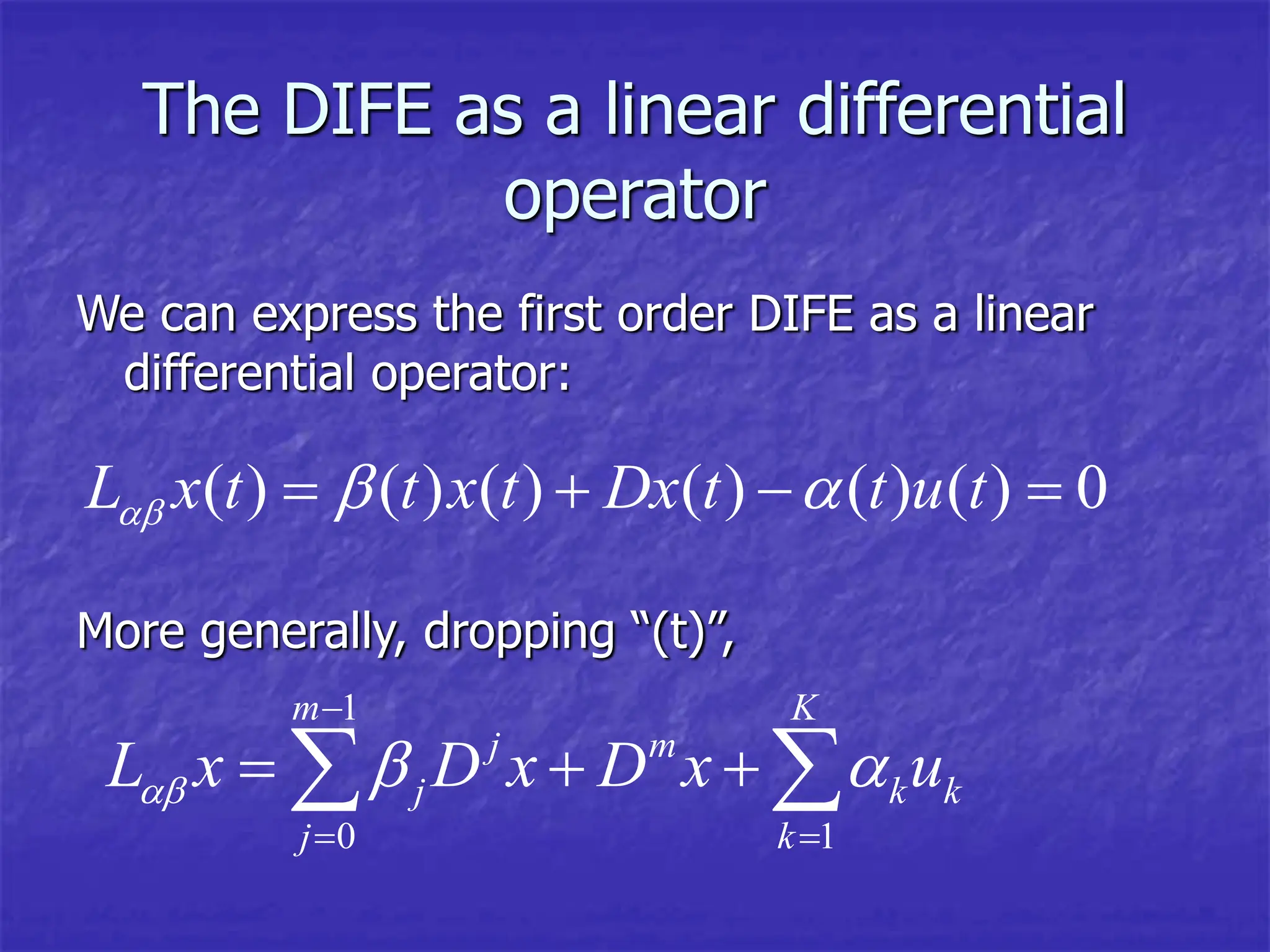

![A constant coefficient example

We can see more clearly what happens

when

Coefficients α and β are constants,

u(t) is a function stepping from 0 to 1

at time t1:

1

( )

1

( ) [1 ],

t t

x t e t t

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fromdatatodifferentialequations-231008095055-02399aac/75/from_data_to_differential_equations-ppt-16-2048.jpg)

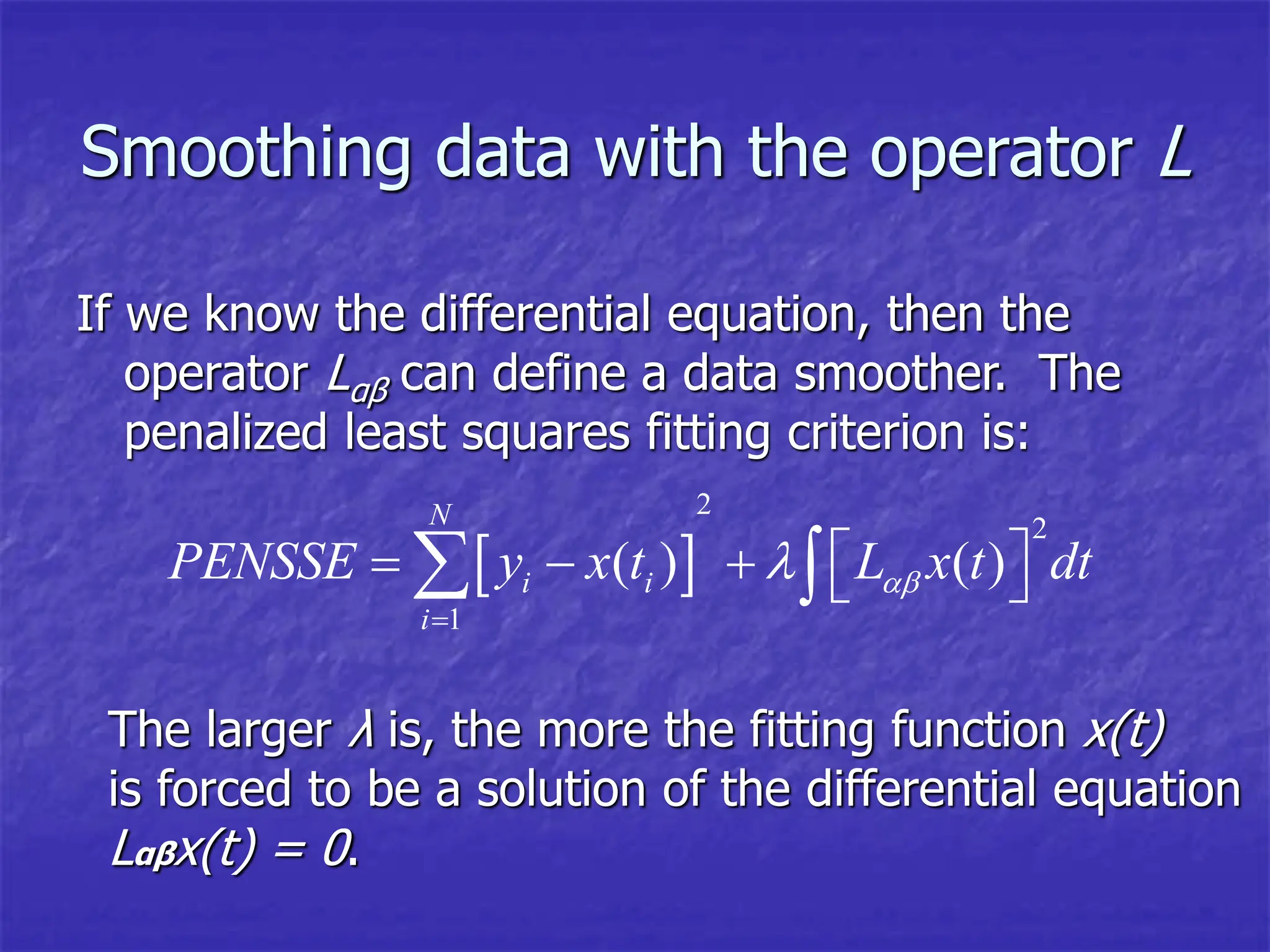

![The smooth values

If x(t) is expanded in terms of a set K basis

functions φk(t), and if N by K matrix Z contains

the values of these functions at time points ti,

then the vector fitting the data is

1

, [ ' , ] '[ , ]

, ', ,

y Z Z Z R Z y s

R L L s L u

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fromdatatodifferentialequations-231008095055-02399aac/75/from_data_to_differential_equations-ppt-21-2048.jpg)