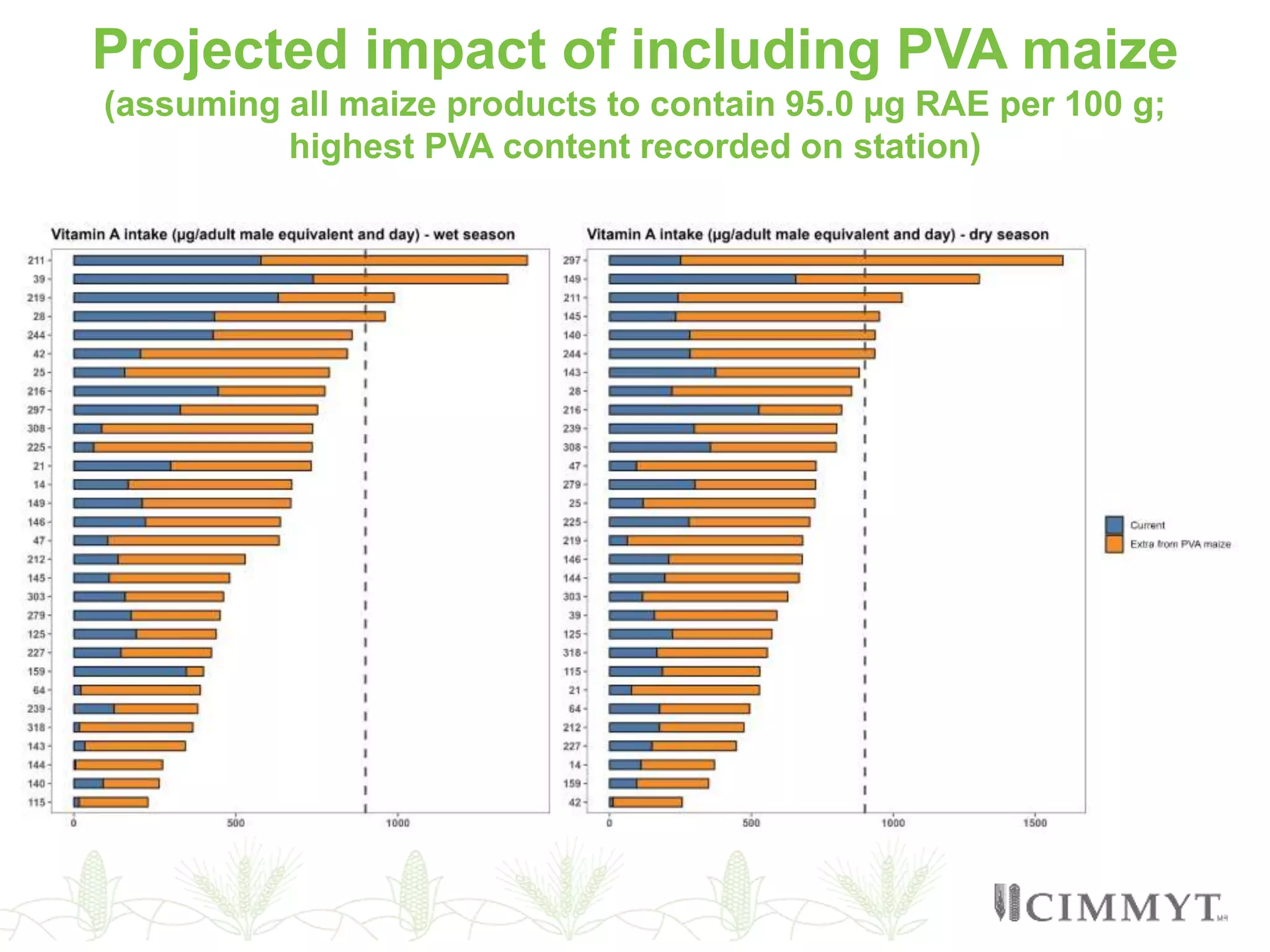

The document assesses nutrient adequacy and diet costs among rural households in Zimbabwe, highlighting a year-round inadequacy of vitamin A intake across different farm types. It suggests that large-scale adoption of pro-vitamin A enriched maize could improve dietary quality, but must be combined with other nutrition interventions to ensure overall sufficiency. Additionally, the study emphasizes the need for affordable nutrient-dense food and nutrition education to foster dietary diversity.