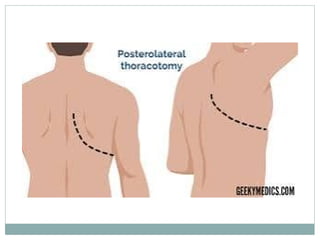

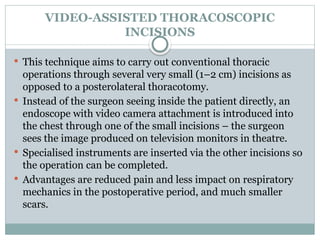

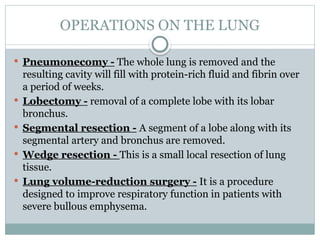

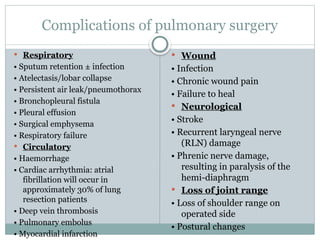

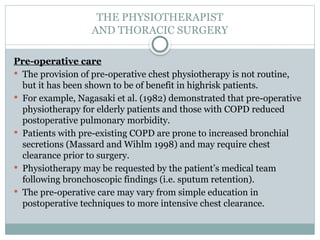

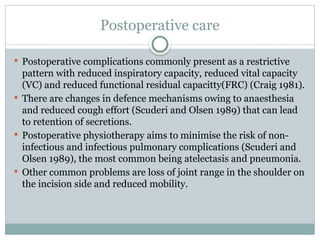

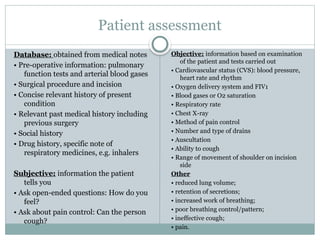

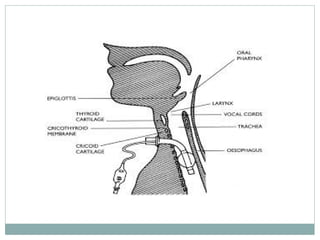

The document provides an overview of thoracic anatomy, surgical indications, and the techniques involved in thoracic surgery, including types of incisions and their respective muscle involvement. It discusses the role of physiotherapy in pre-operative and post-operative care, emphasizing the importance of lung volume maximization, sputum clearance, and early mobilization. Additionally, the document outlines various adjuncts to physiotherapy, such as incentive spirometry and continuous positive airways pressure, and highlights the significance of communication within the healthcare team throughout the patient’s recovery process.