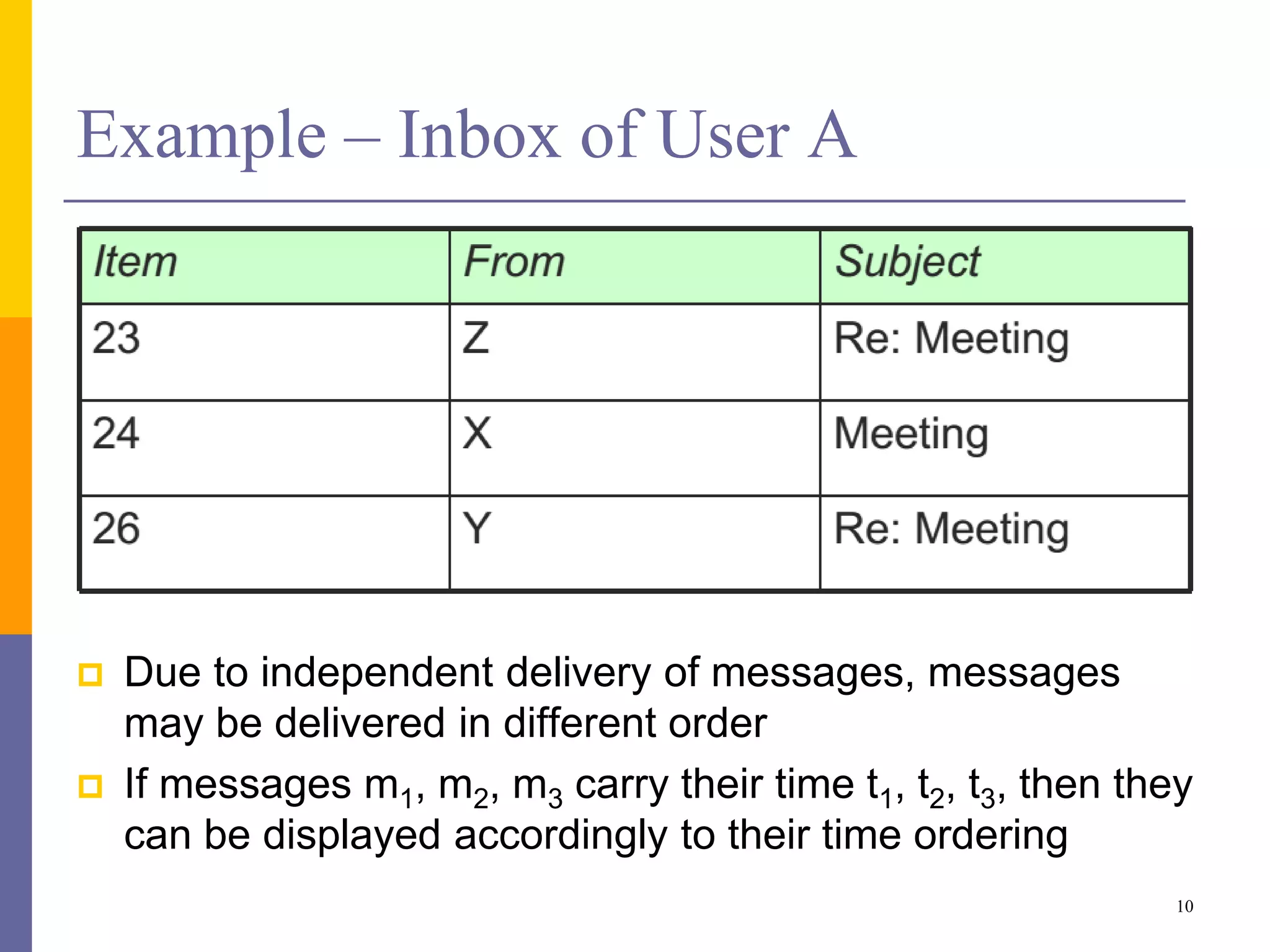

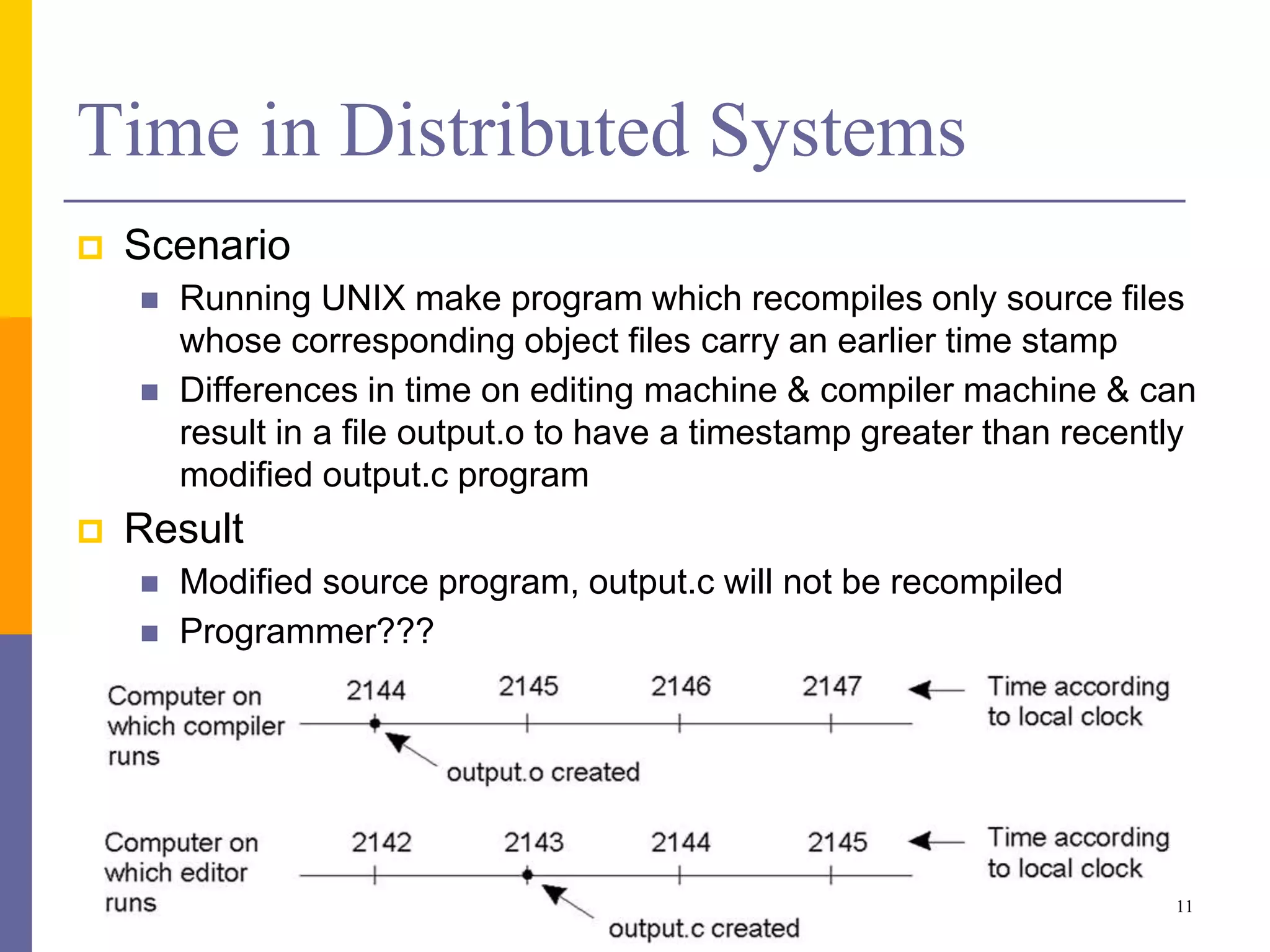

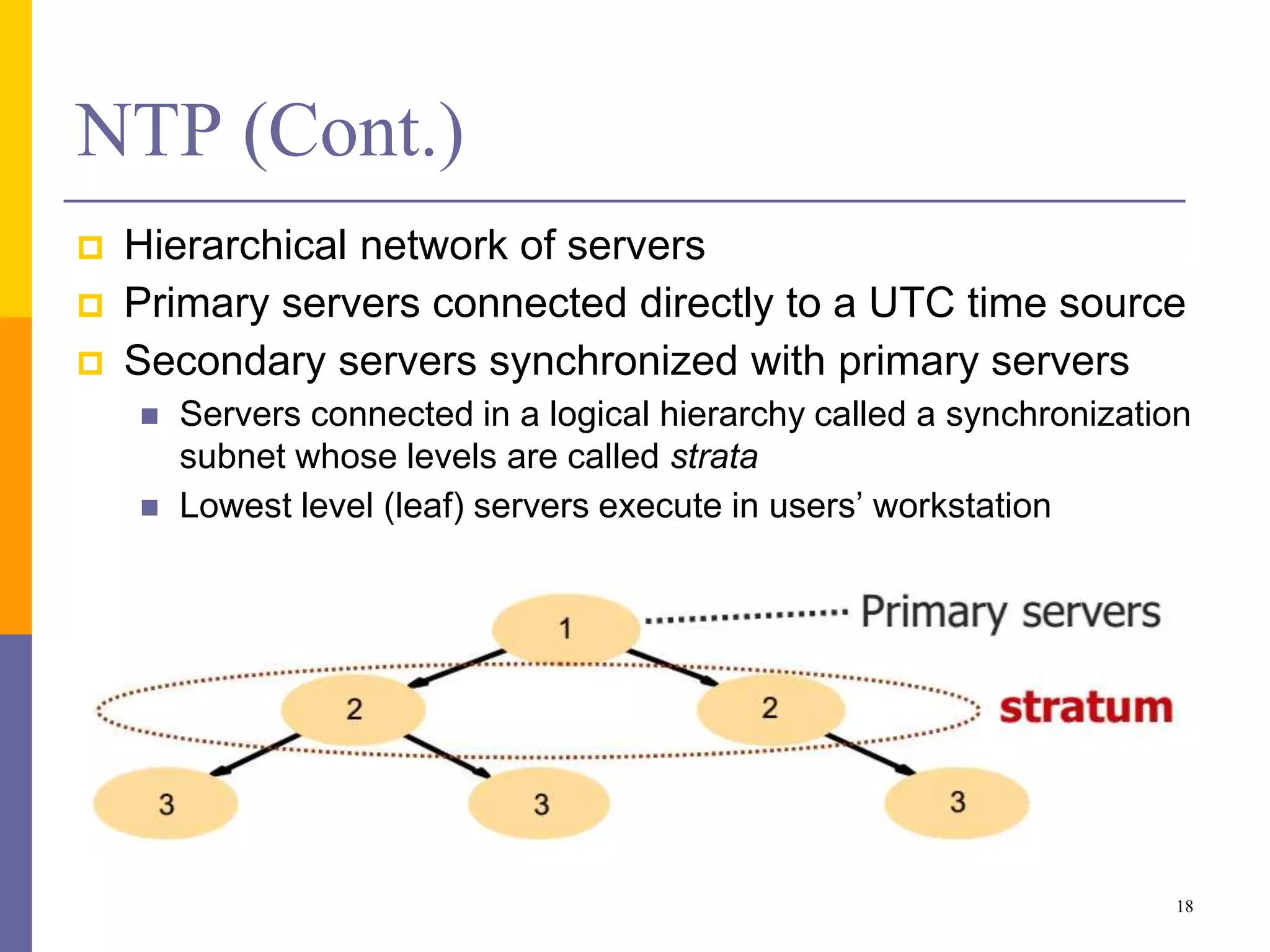

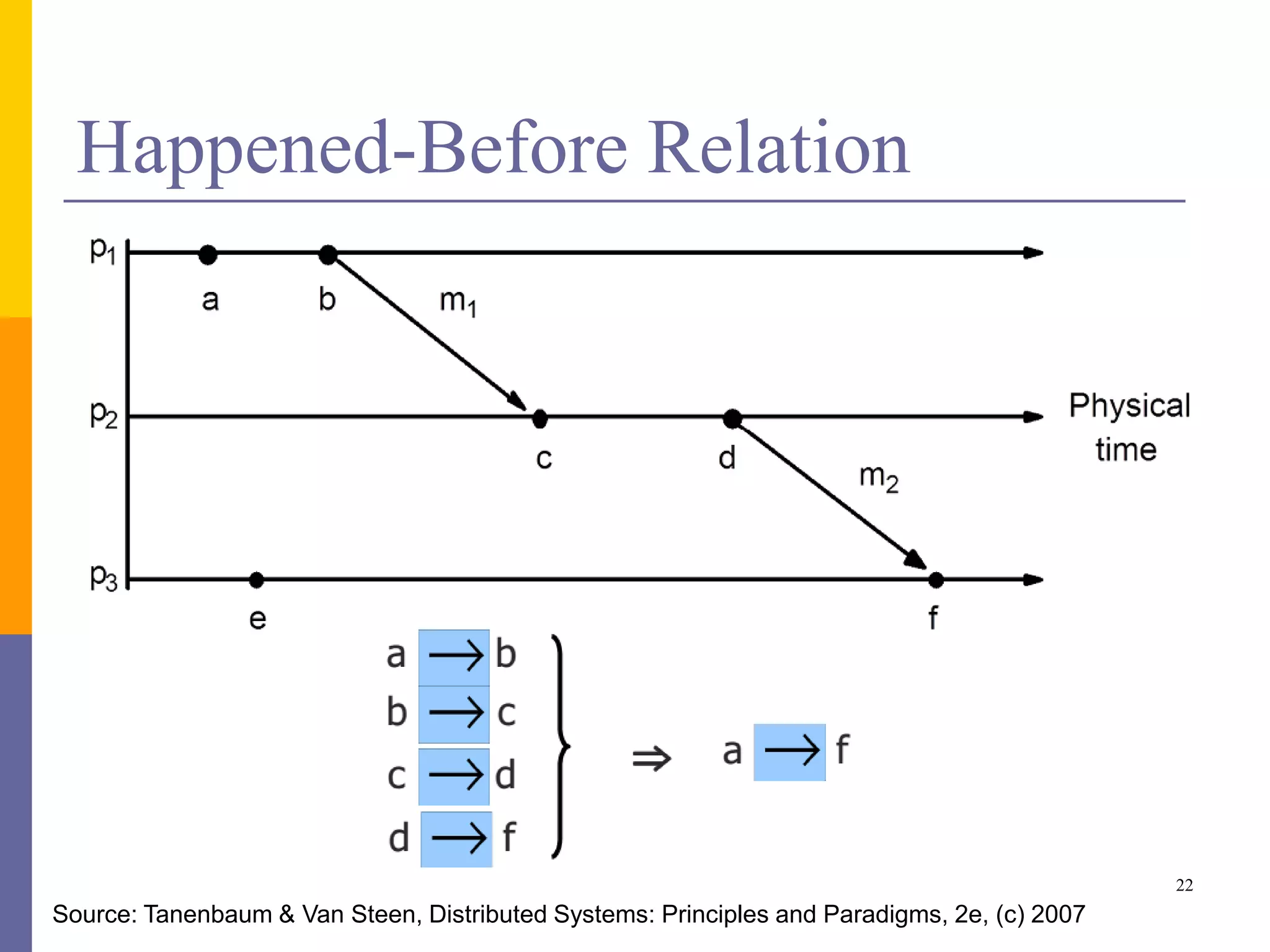

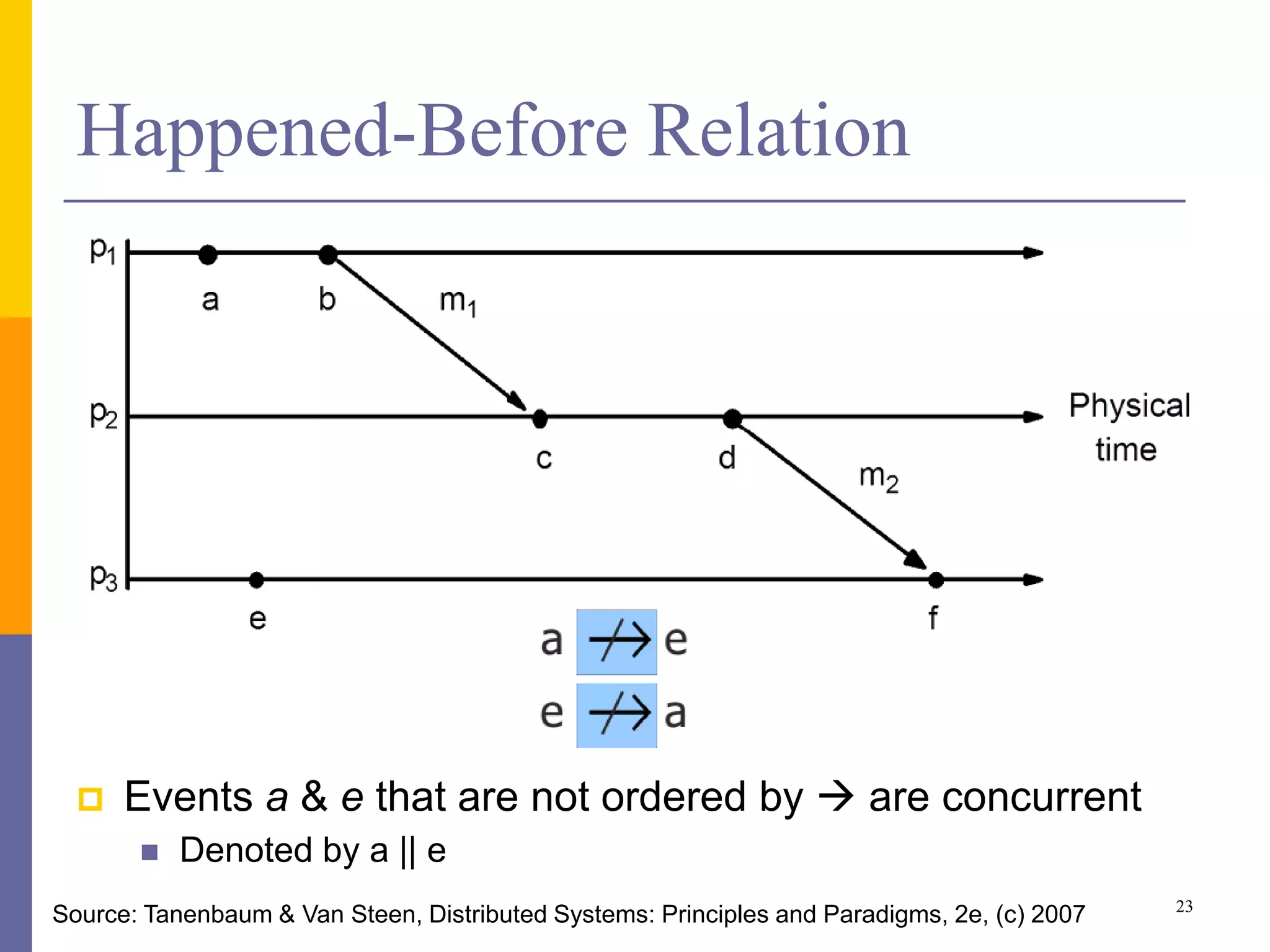

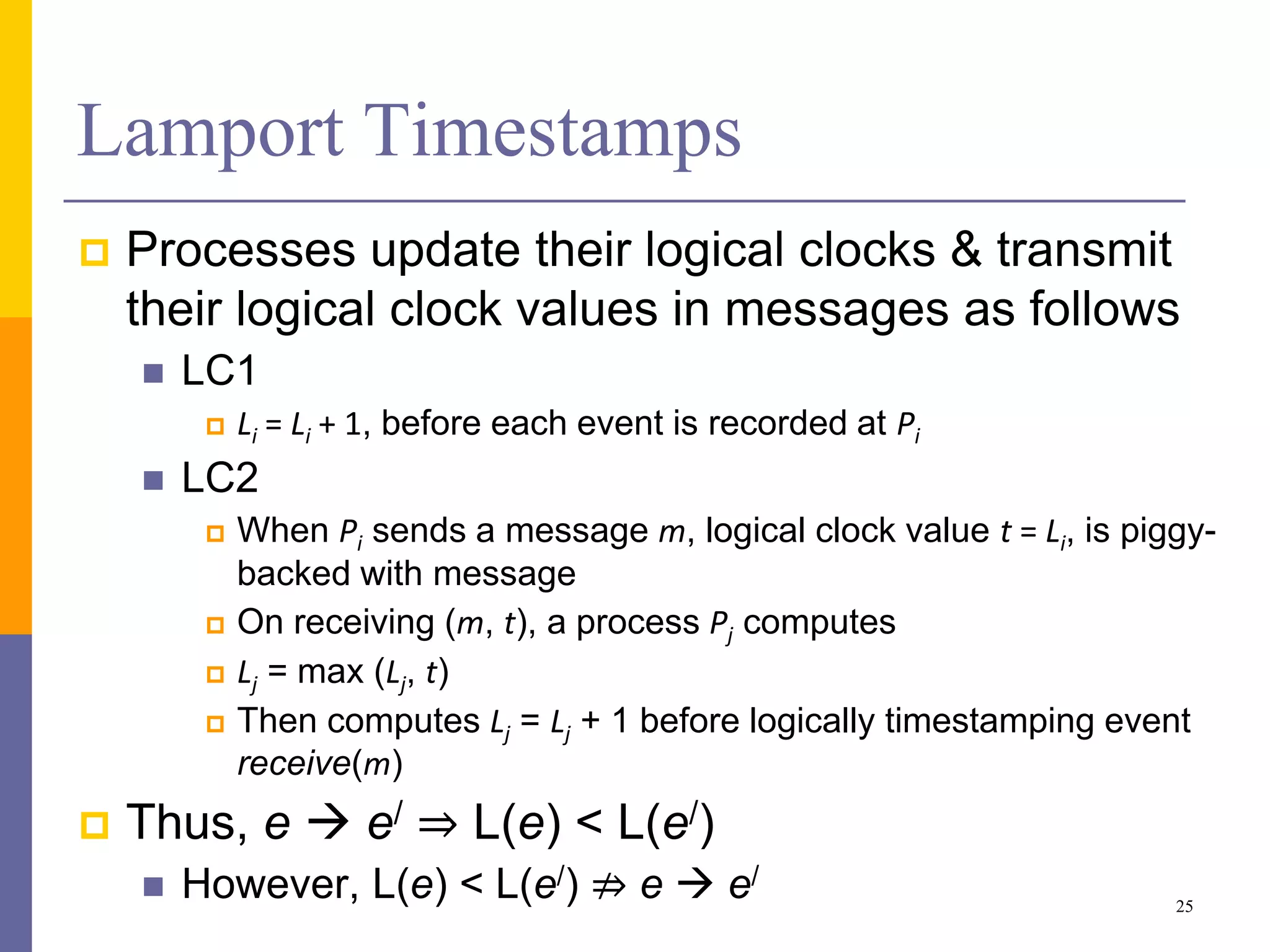

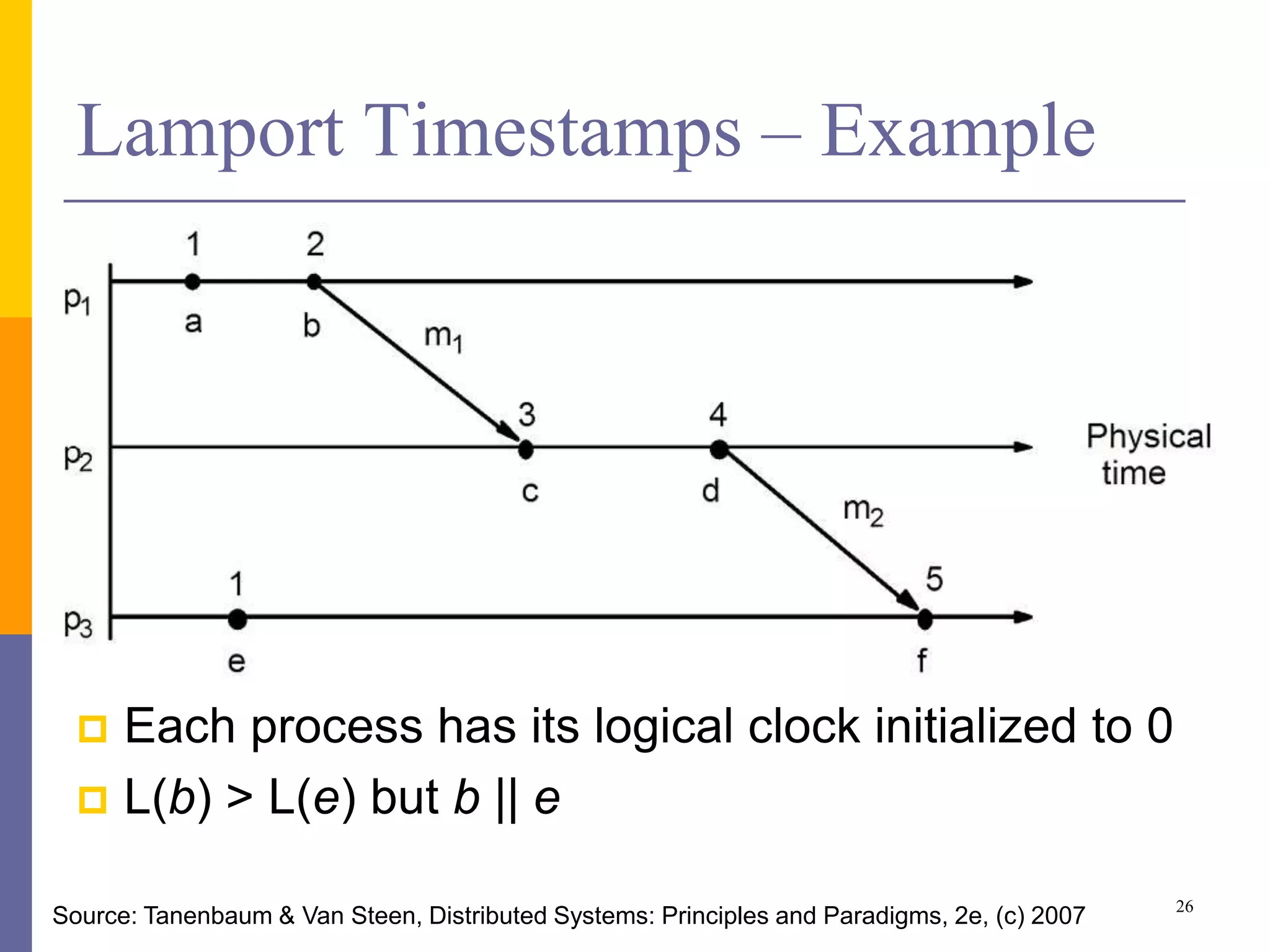

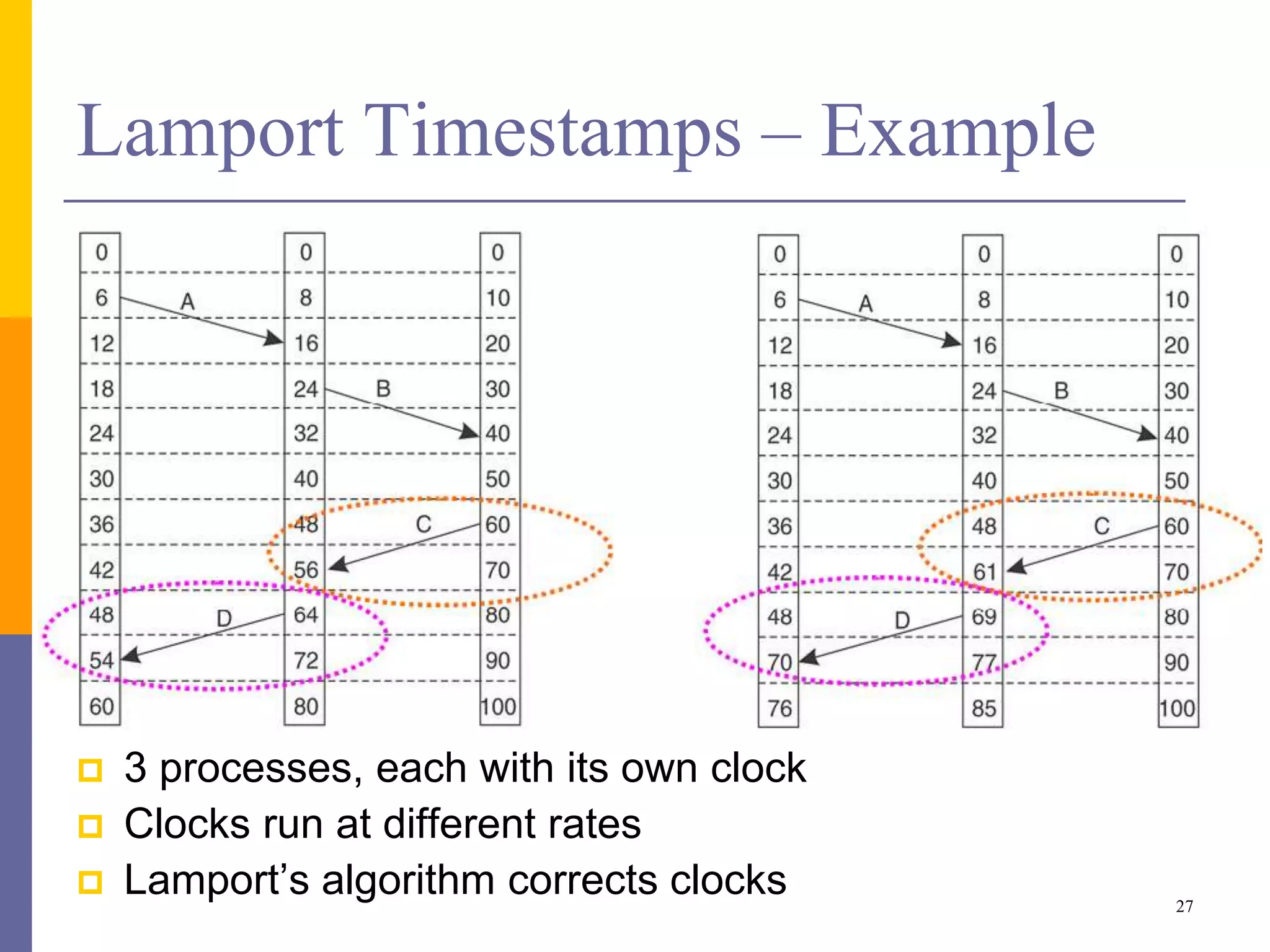

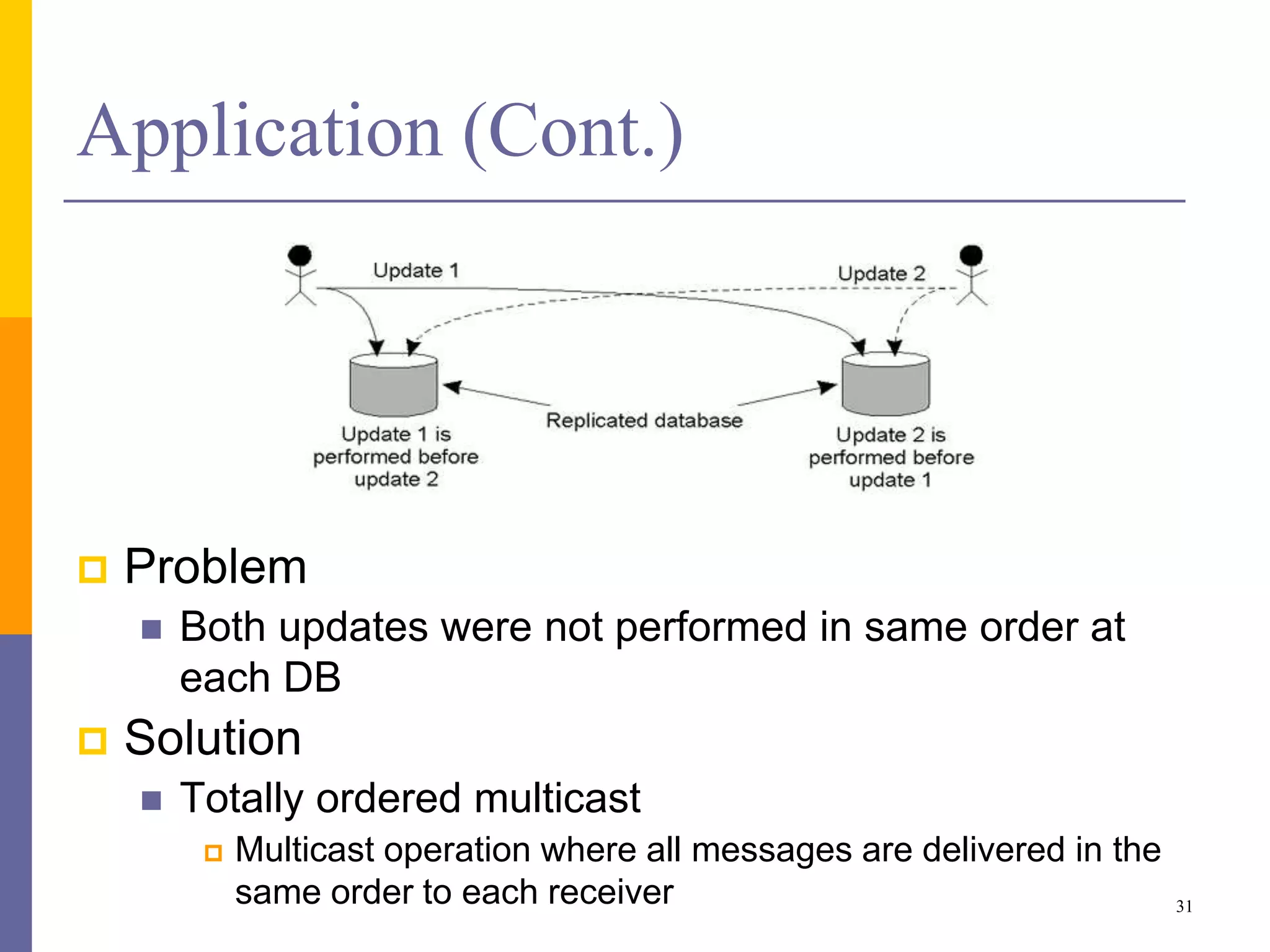

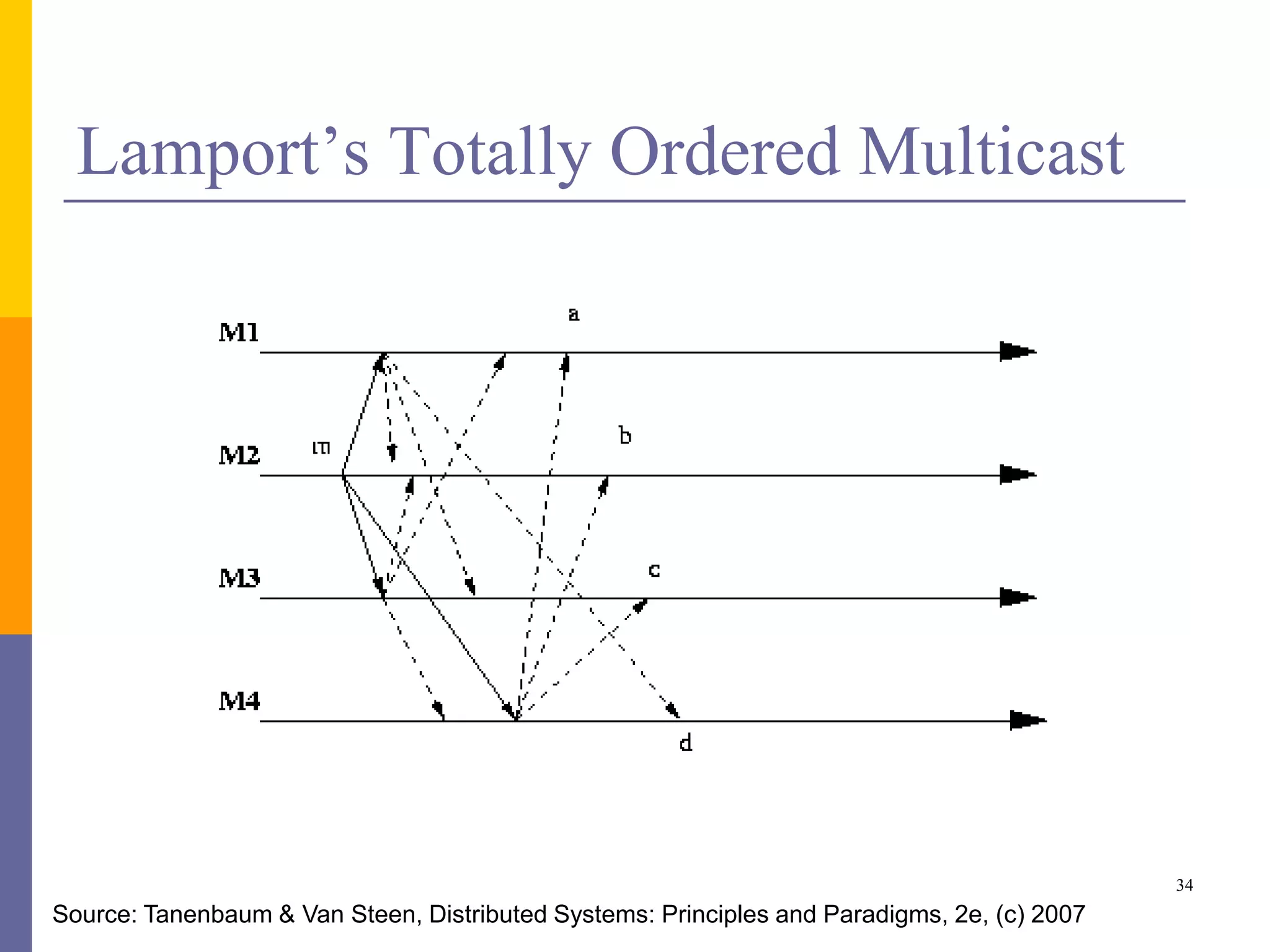

The document provides an overview of time synchronization in distributed systems, discussing both physical and logical clocks, and the challenges posed by clock drift and skew. Key concepts include different models of interaction (synchronous and asynchronous), Lamport's logical clock for event ordering, and the implementation of totally ordered multicast for consistent message delivery in replicated databases. Various algorithms, including the Network Time Protocol, are also highlighted for achieving synchronization across systems.