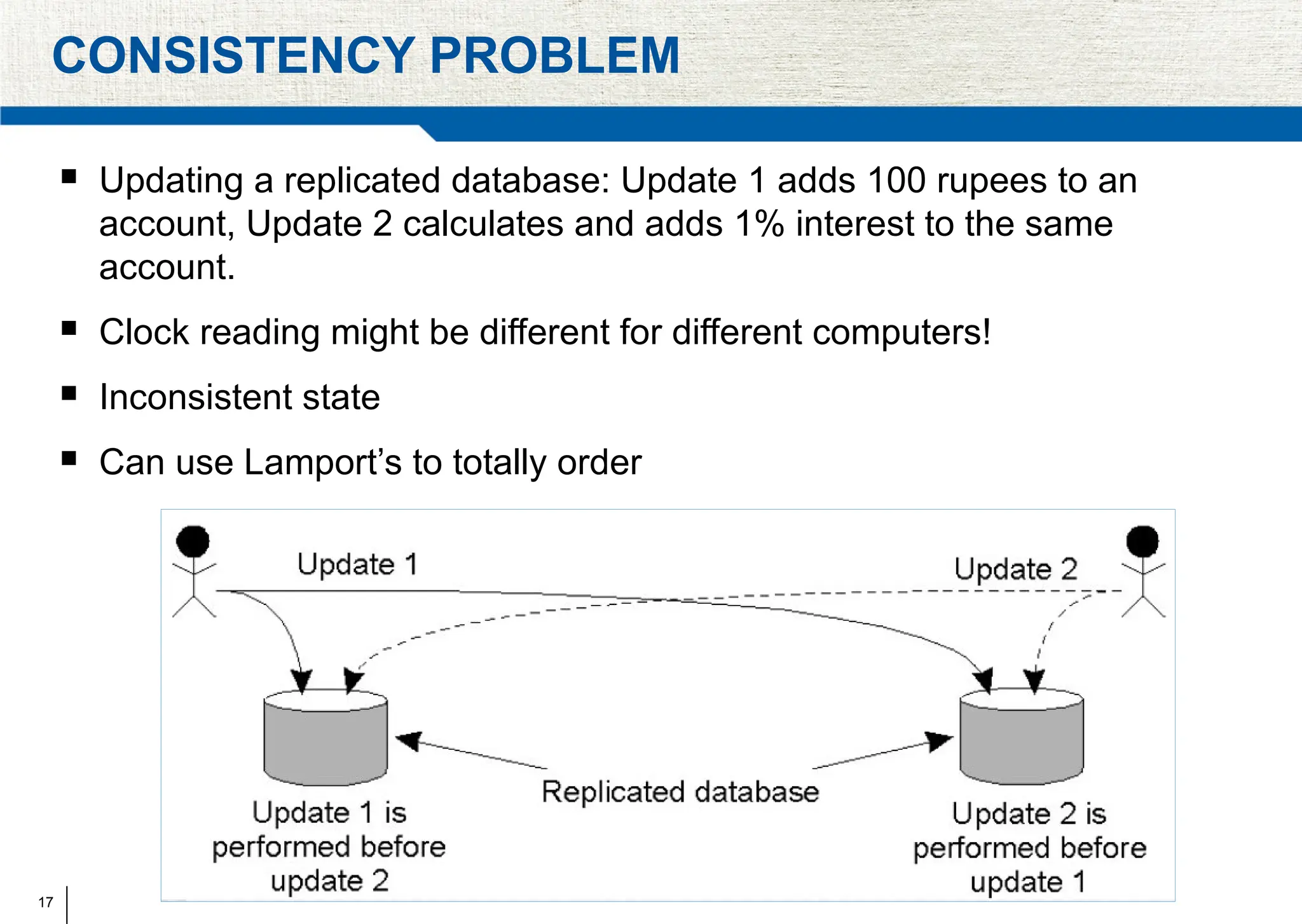

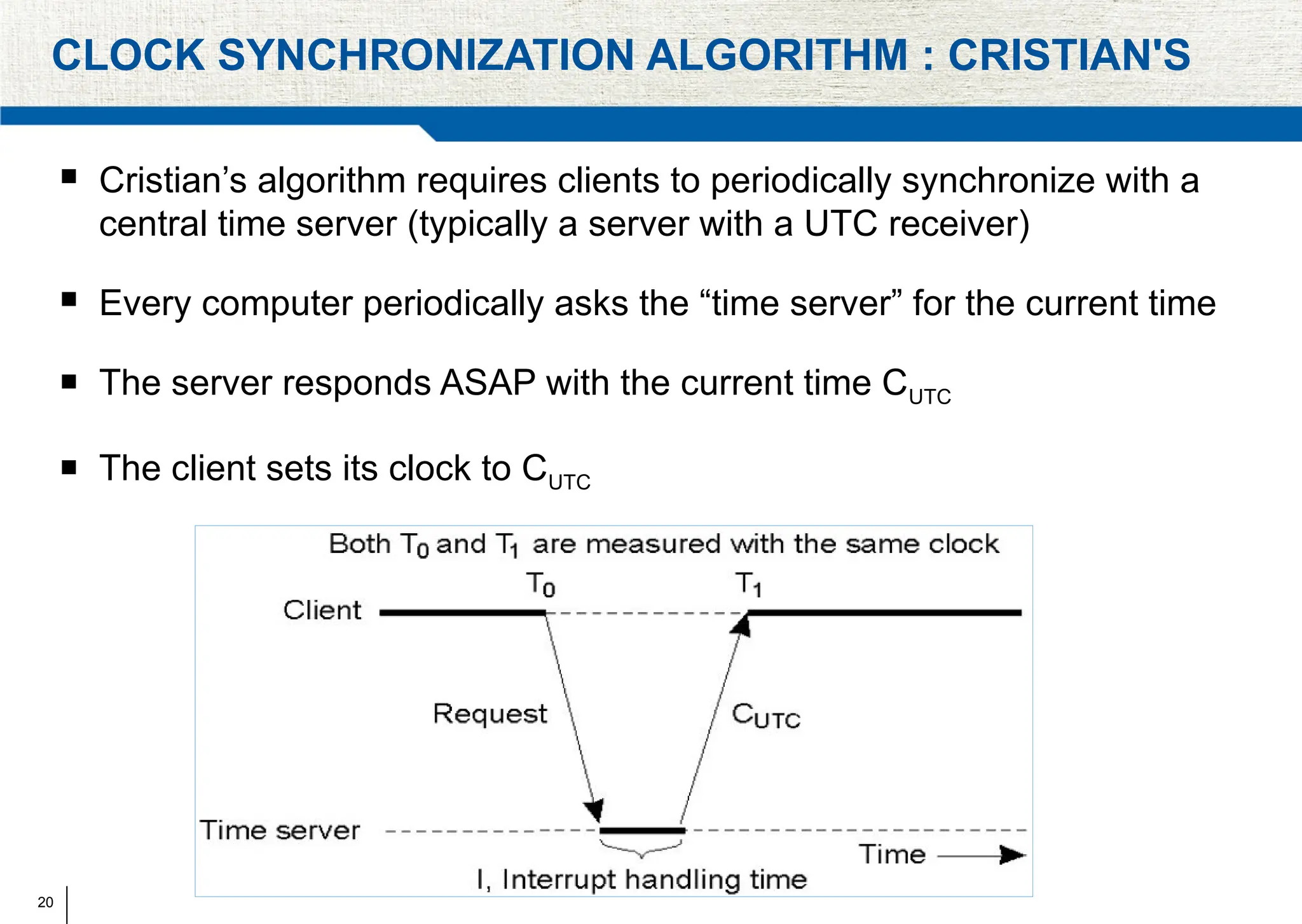

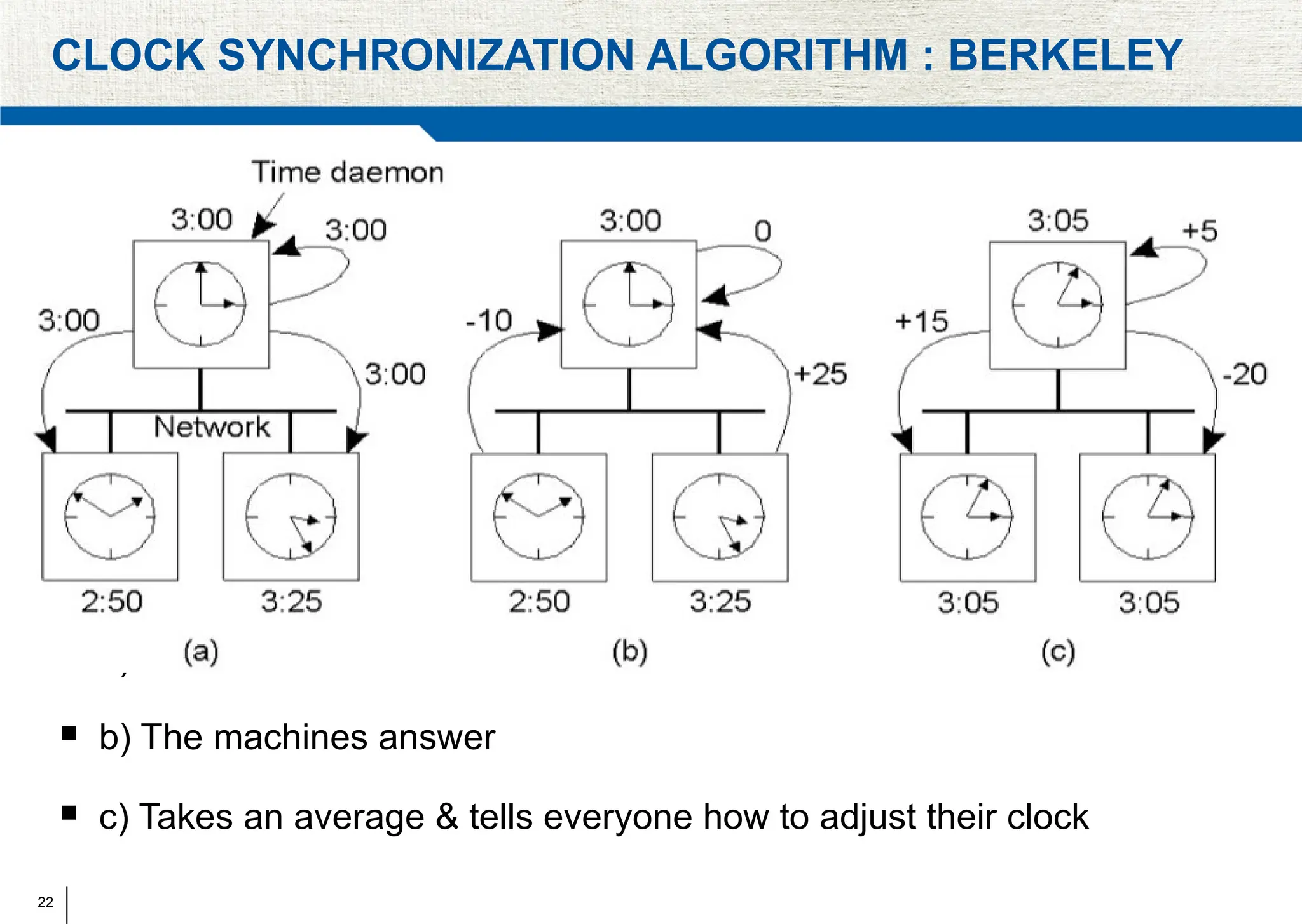

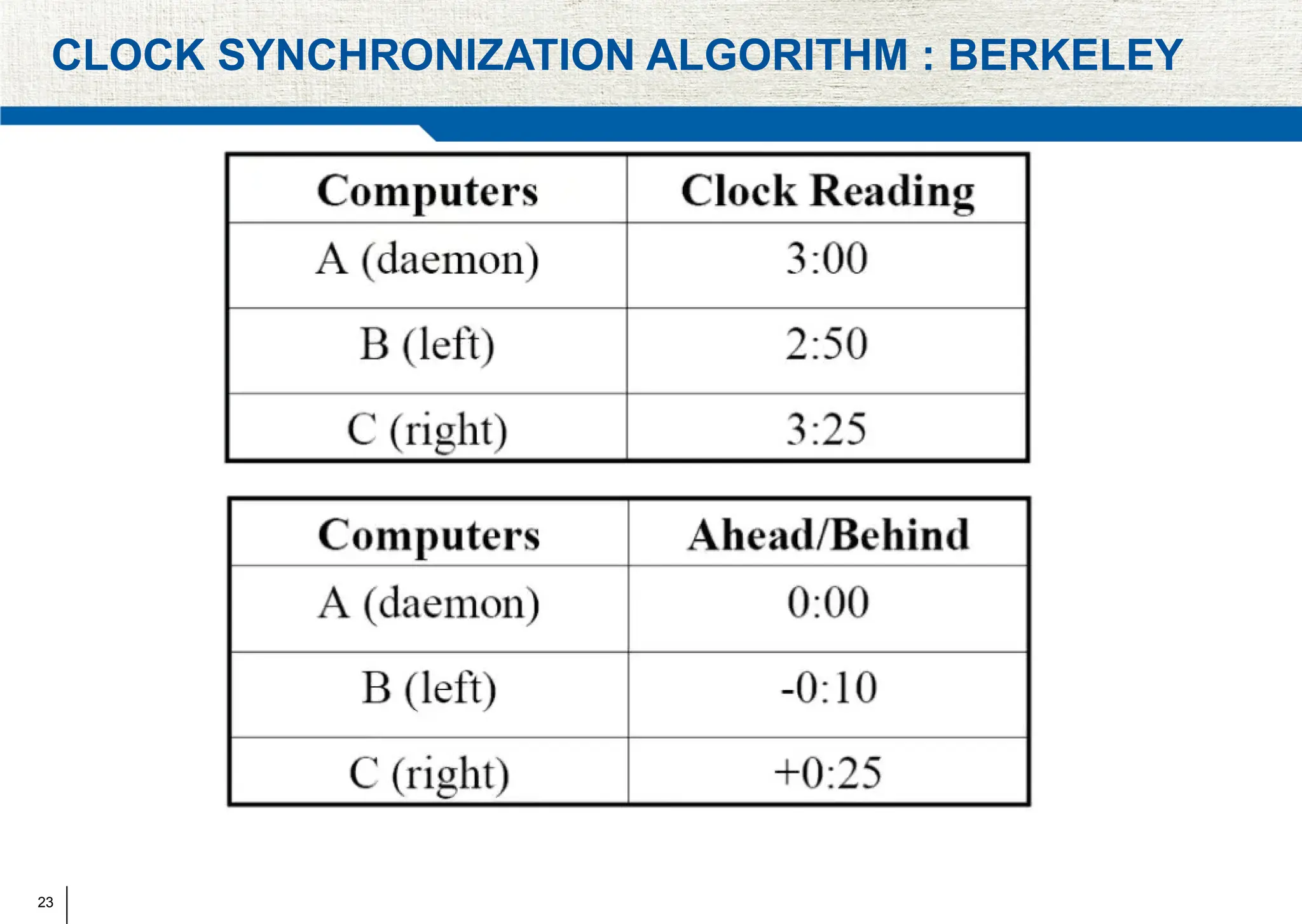

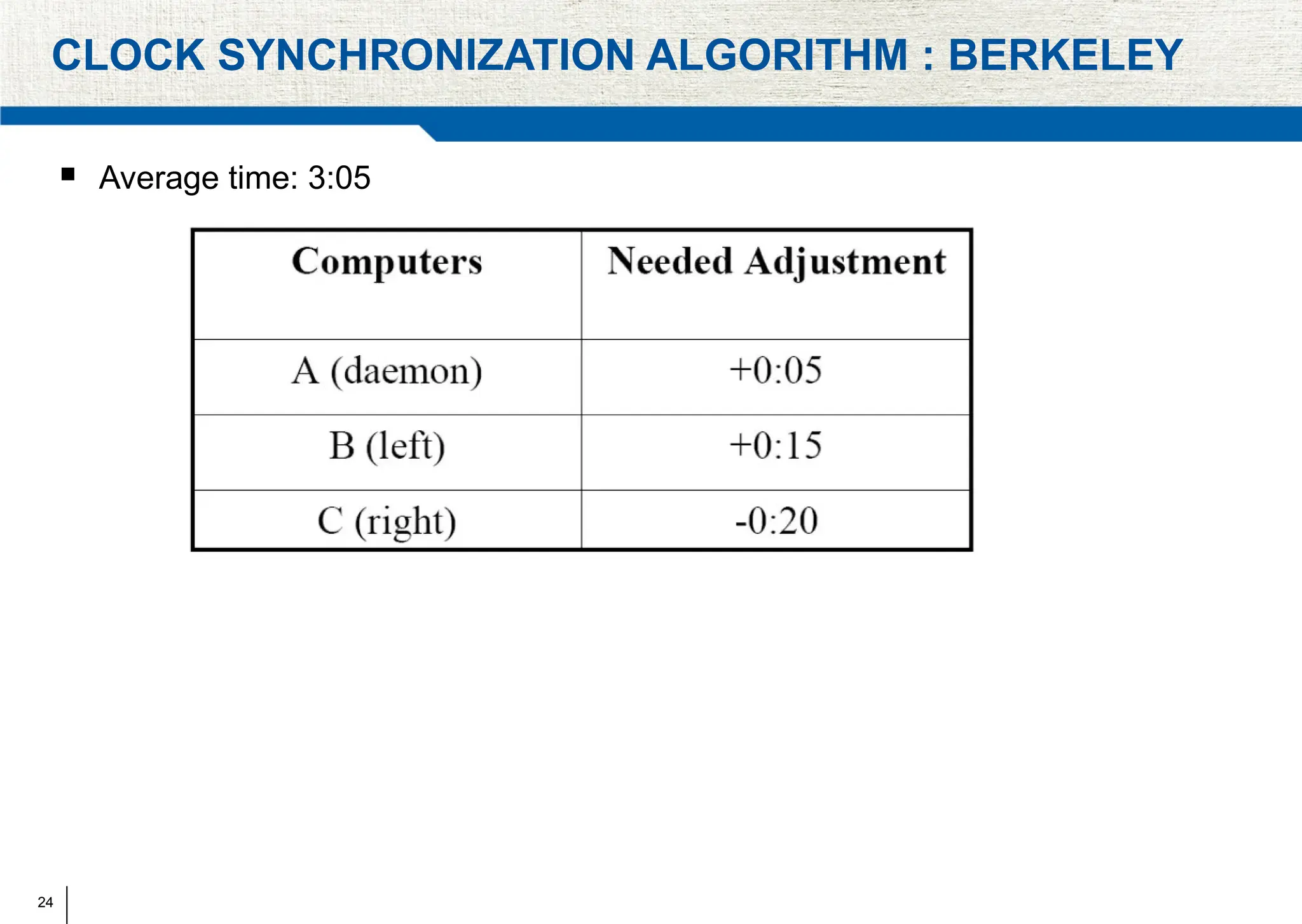

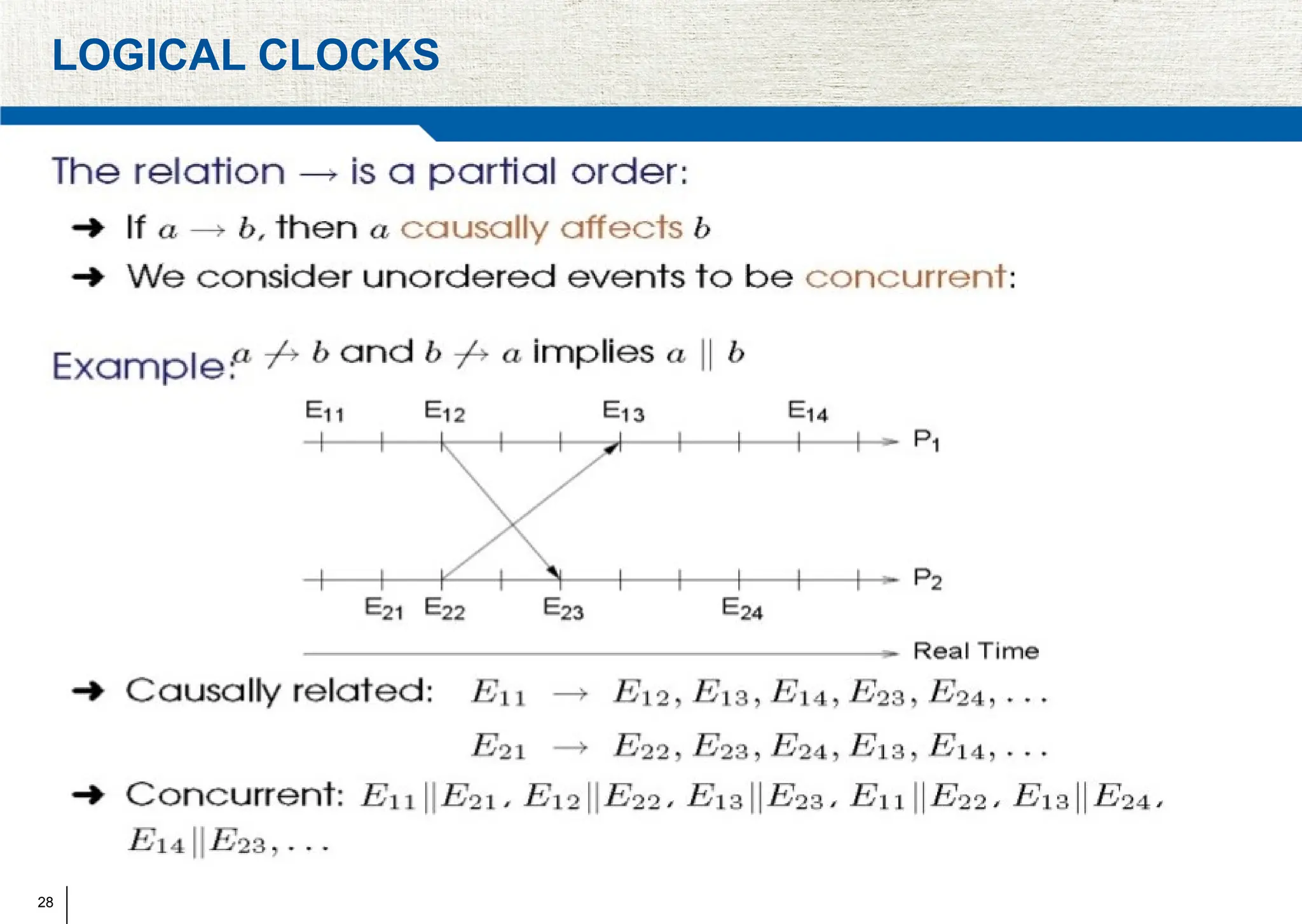

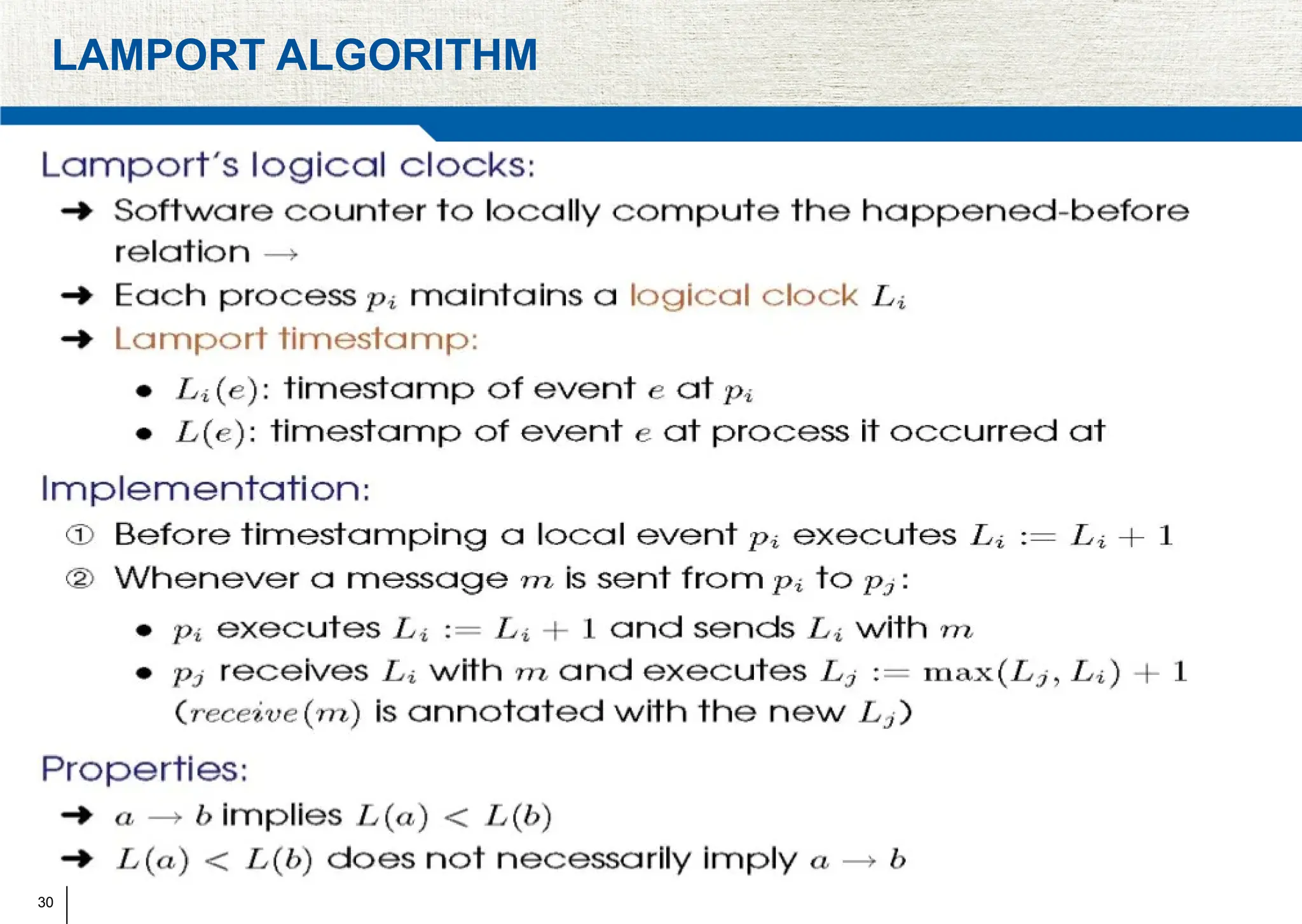

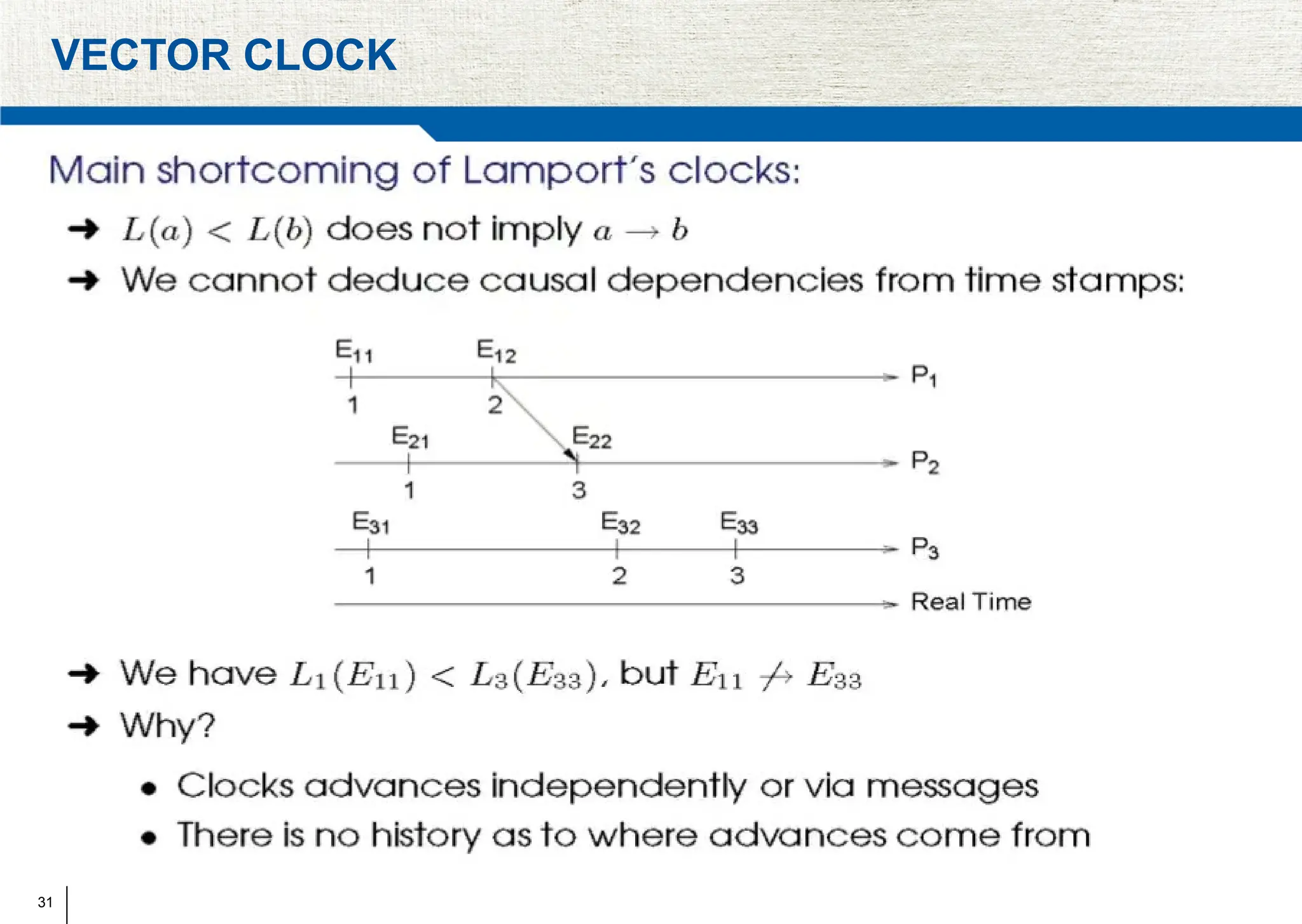

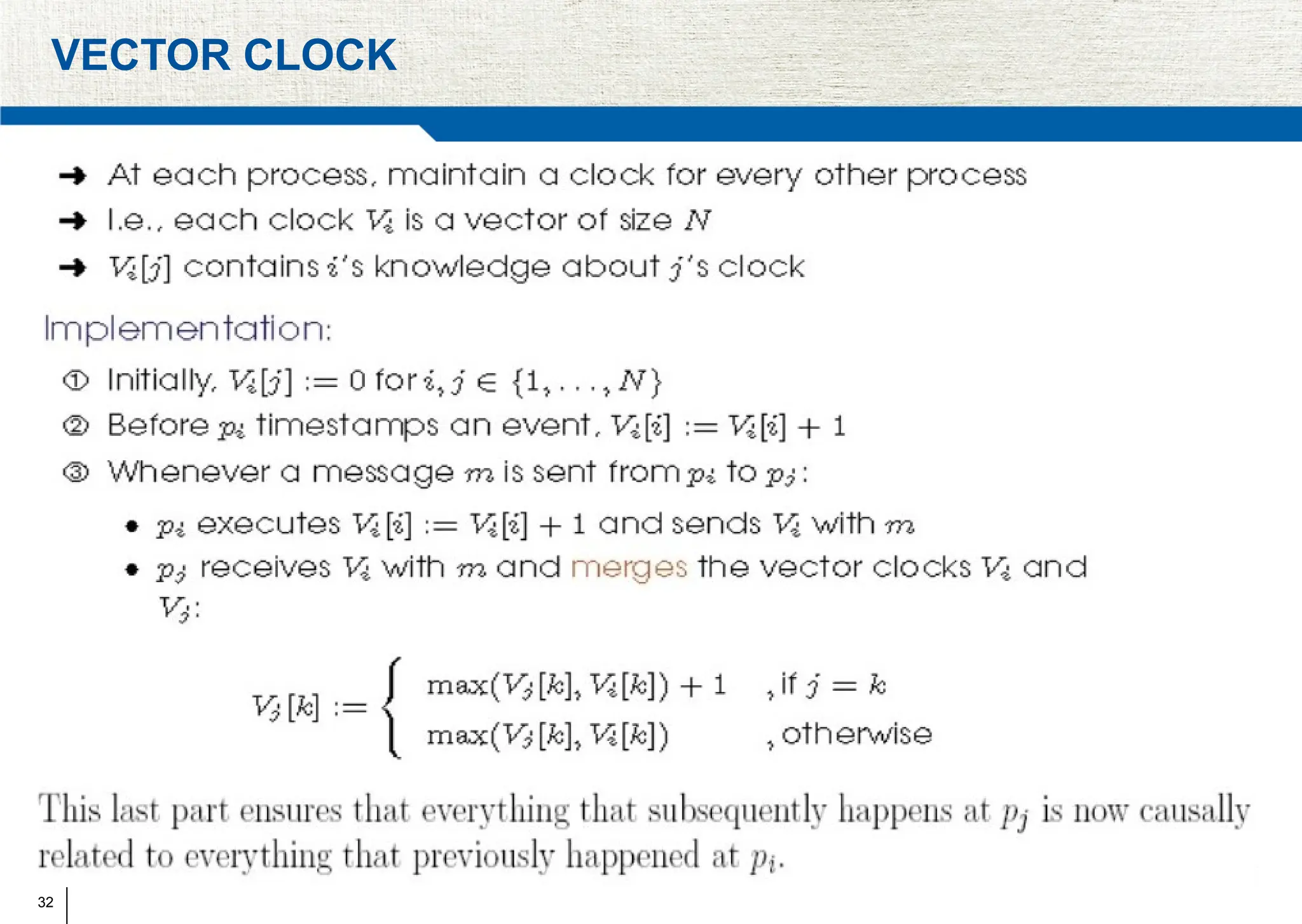

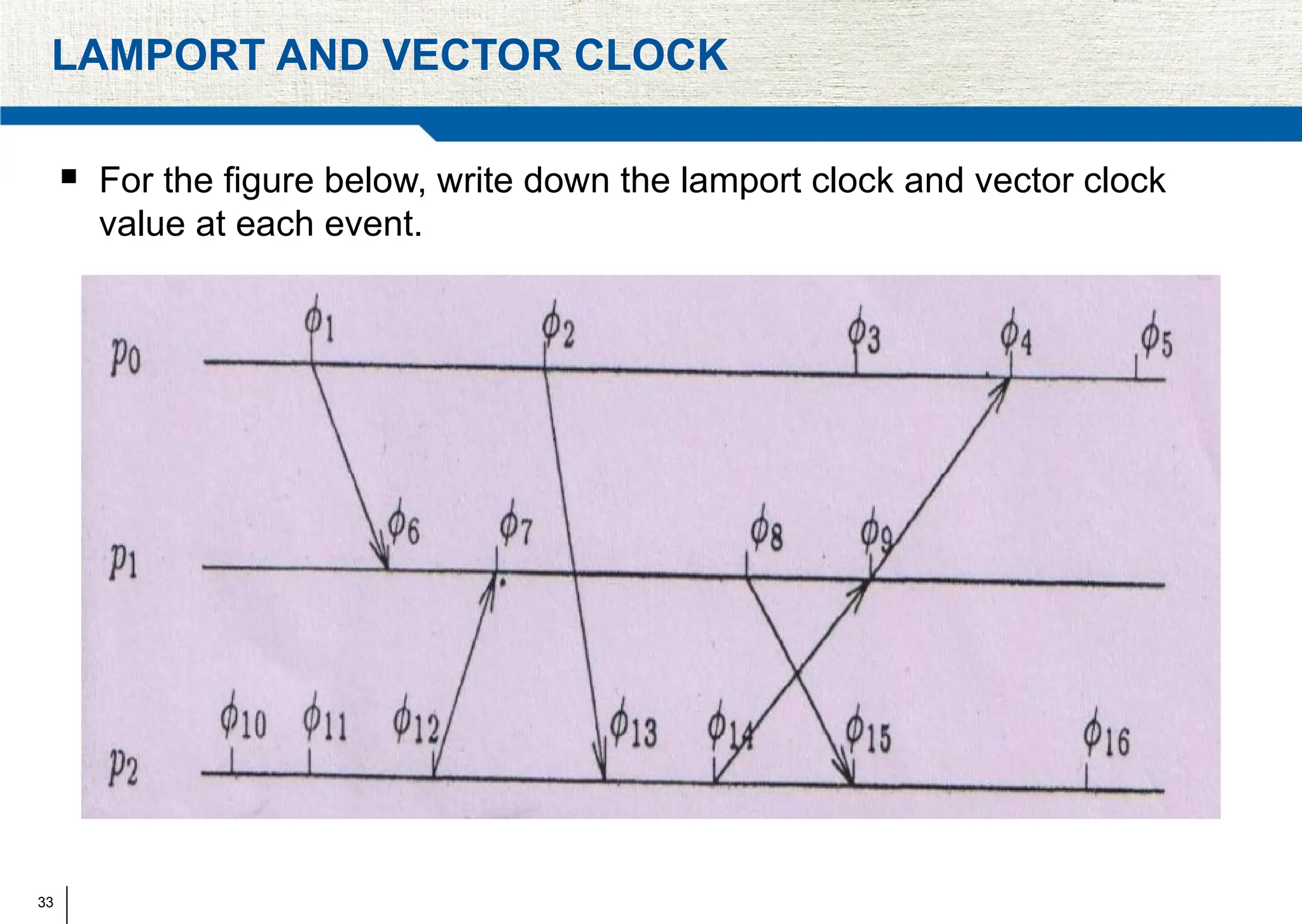

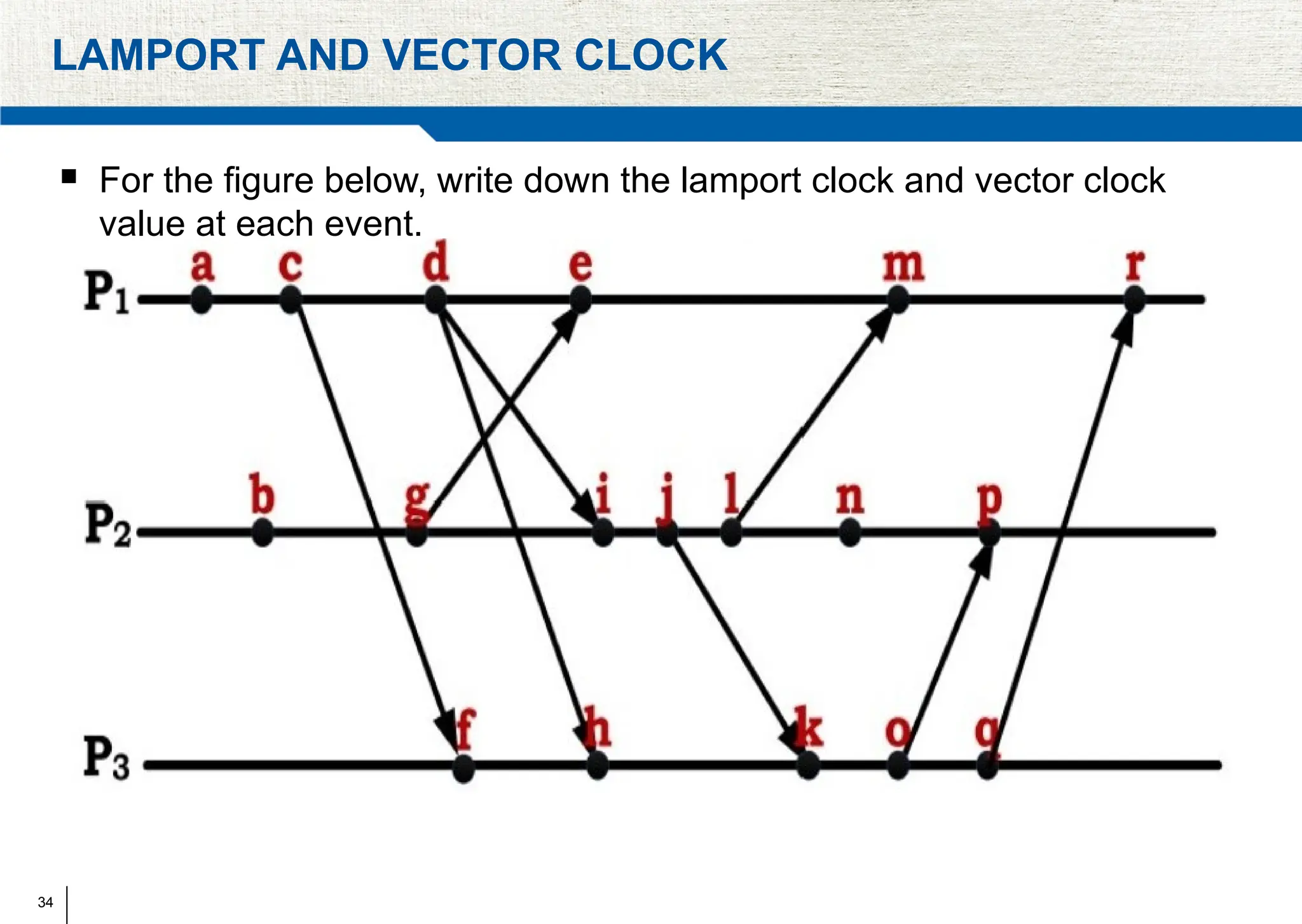

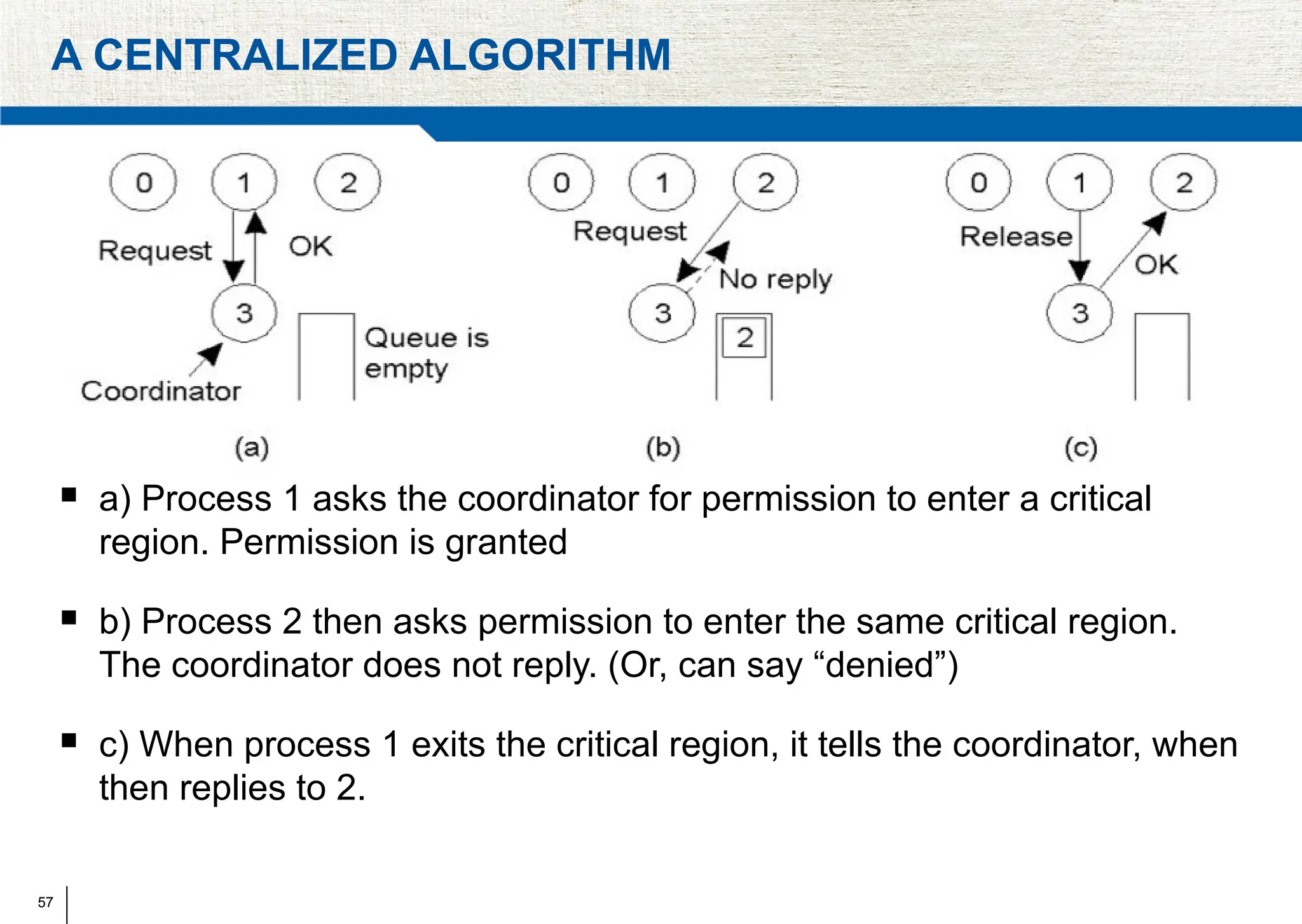

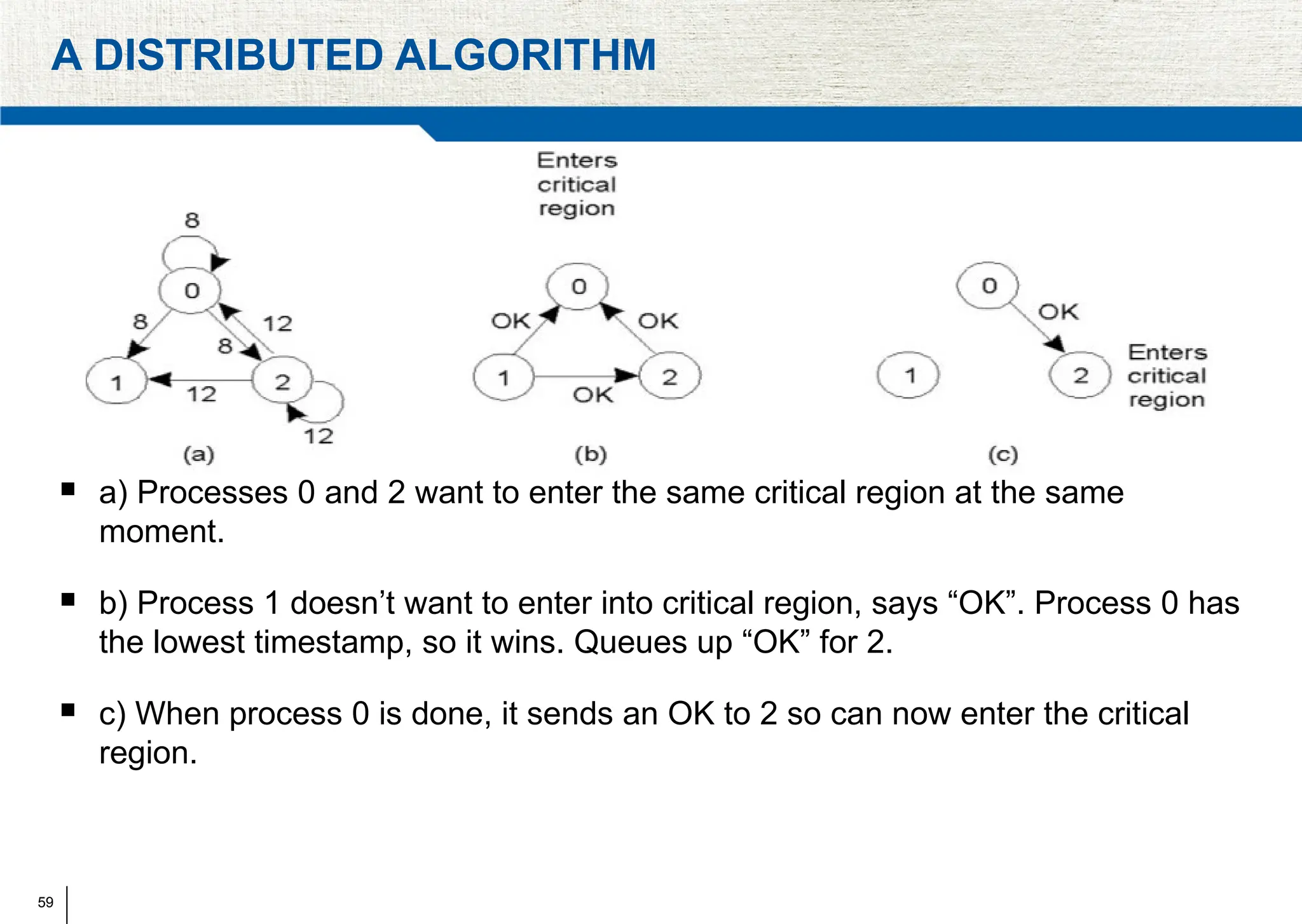

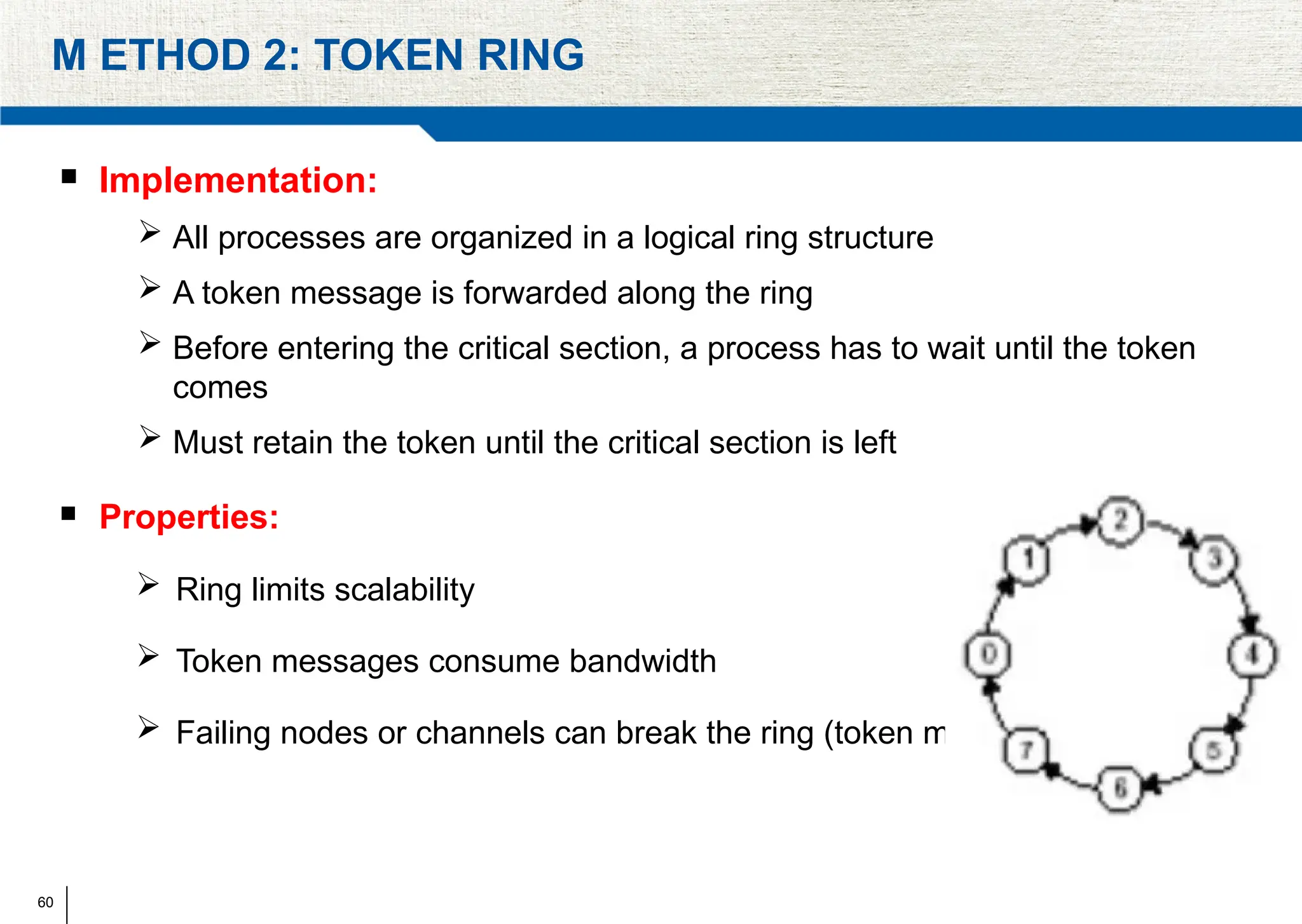

The document covers synchronization in distributed computing, outlining key topics such as distributed algorithms, coordination, time management, and concurrency control. It distinguishes between synchronous and asynchronous systems, discusses clock synchronization methods, and addresses challenges in determining global states within these systems. Additionally, it explores various mutual exclusion mechanisms and their comparative advantages, including centralized, token ring, and multicast approaches.