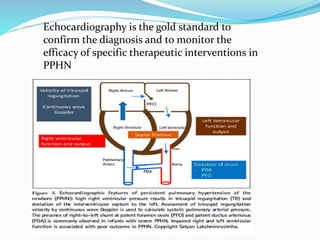

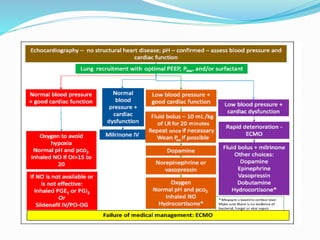

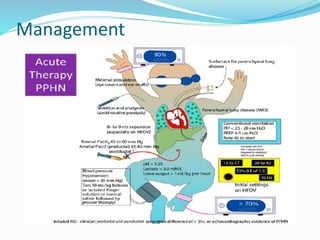

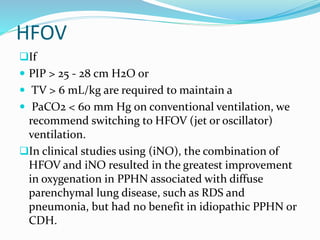

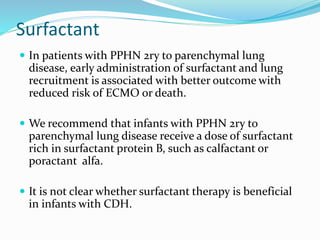

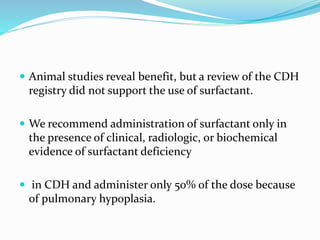

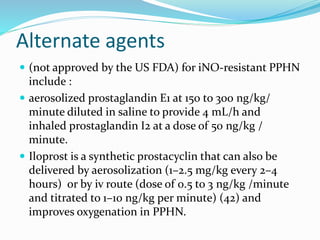

This document discusses persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN). It defines PPHN as failure of the normal circulatory transition at birth, causing elevated pulmonary vascular resistance and decreased pulmonary blood flow. The document covers the incidence, etiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis and management of PPHN. Key aspects of management include supportive care, gentle mechanical ventilation, use of inhaled nitric oxide and high-frequency oscillatory ventilation in severe cases.