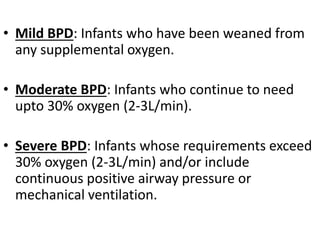

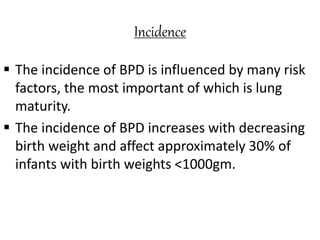

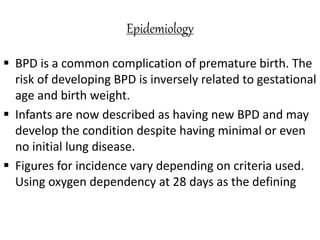

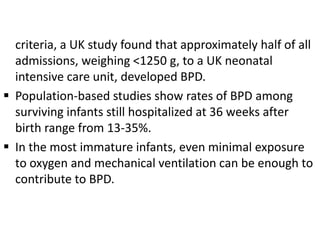

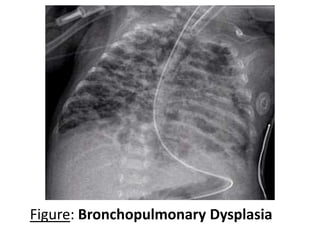

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) is a chronic lung disease affecting premature infants, characterized by a need for oxygen support beyond 28 days postnatally, with severity categorized as mild, moderate, or severe based on oxygen requirements. The incidence of BPD is significantly influenced by factors like birth weight and gestational age, with about 30% of infants weighing less than 1000g affected. Management focuses on preventing further lung injury through respiratory support, nutrition, and careful monitoring, with long-term outcomes potentially including chronic respiratory issues and neurodevelopmental delays.