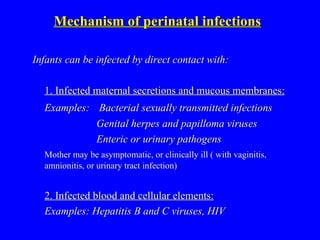

The document discusses strategies for preventing perinatal infections. It reviews major bacterial and viral infections, risk factors, diagnostic and treatment approaches, and examples of effective prevention measures. Key prevention strategies include prenatal screening and treatment, vaccination programs, and guidelines for managing at-risk pregnancies and deliveries. National recommendations and monitoring have significantly reduced rates of certain infections.

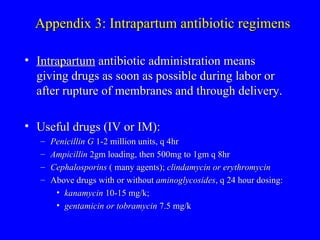

![Prevention of perinatal GBS infection: Setting up strategies 1. Screening-based approach Collect rectal-vaginal swab for GBS at 35-37 weeks Give intrapartum Penicillin if screen (+). [ Intrapartum chemoprophylaxis means administration of antibiotics after the onset of labor or rupture of membranes but before delivery] 2. Risk-factor approach Give intrapartum Penicillin to women who have any of the following risks: - Previously delivered infant with GBS -GBS bacteriuria during pregnancy -Delivery @ < 37 weeks-gestation -Duration of rupture of membranes > 18 hours -Intrapartum temperature > 38C](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/perinatalinfectionsmarch02-100401124624-phpapp01/85/Perinatal-Infections-18-320.jpg)