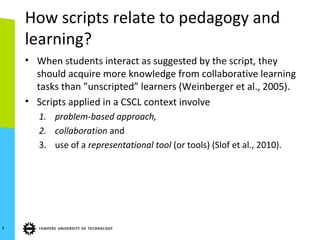

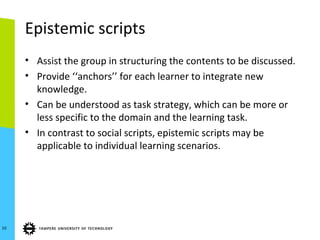

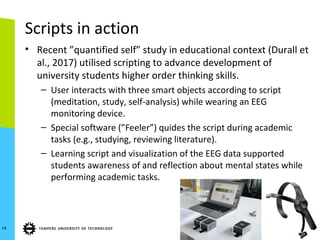

The document discusses pedagogical scripting in Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning (CSCL), defining scripts as structured activity programs intended to enhance collaborative learning by assigning and sequencing tasks among learners. It emphasizes the importance of scripting in promoting collaboration and knowledge construction while detailing various types of scripts, including epistemic and social/collaboration scripts, which guide learners in both knowledge acquisition and effective interaction. Additionally, it addresses the role of representational tools and offers examples of successful script implementations that foster higher-order thinking skills among university students.