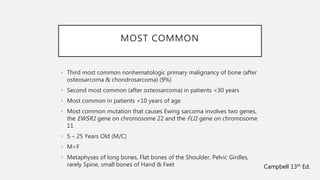

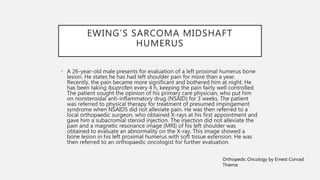

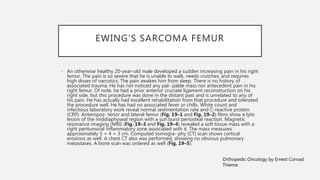

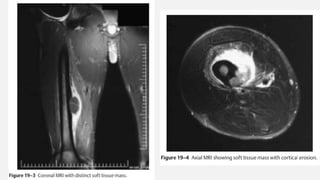

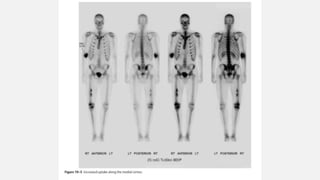

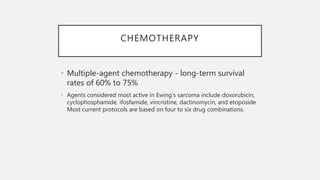

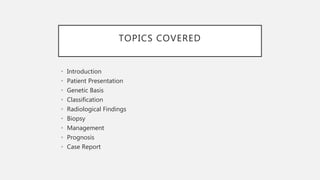

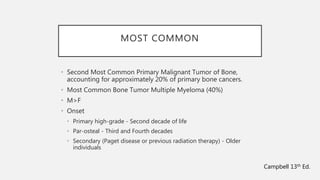

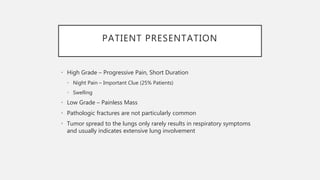

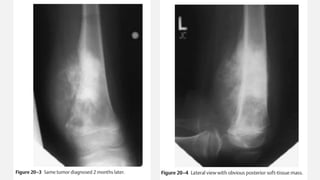

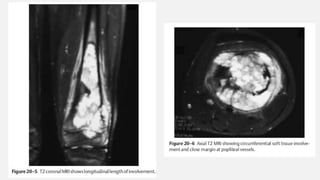

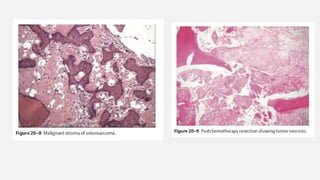

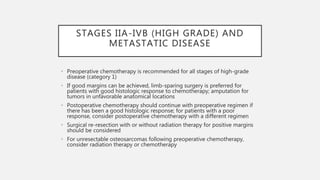

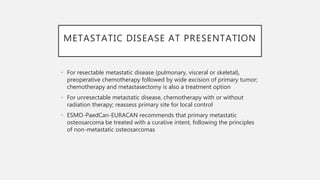

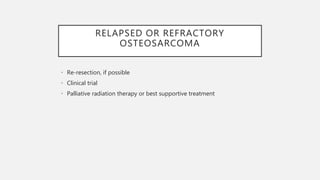

This document provides an overview of osteosarcoma and Ewing's sarcoma, including their genetic basis, clinical presentation, radiological findings, biopsy, management, and prognosis. Osteosarcoma is the second most common primary bone cancer and most commonly affects the metaphysis of long bones in adolescents and young adults. Presentation includes pain, swelling, and sometimes pathological fractures. Diagnosis involves imaging such as X-ray, CT, MRI and biopsy. Treatment typically involves neoadjuvant chemotherapy, surgical resection with wide margins, and additional chemotherapy. Prognosis depends on stage and response to treatment, with 5-year survival rates ranging from 60-80% for localized disease.

![NCCN AND ESMO-PAEDCAN-EURACAN

CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINES FOR

TREATMENT OF OSTEOSARCOMA

• Guidelines for the treatment of osteosarcoma have been published by

the following organizations:

• National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) [30]

• European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO), European Reference

Network for Paediatric Cancers (PaedCan), and European Network for

Rare Adult Solid Cancer (EURACAN) [31]

• Guideline recommendations on treatment of osteosarcoma vary by

disease stage.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/osteosarcomaewings-200228154417/85/Osteosarcoma-Ewings-53-320.jpg)

![STAGES IA-IB (LOW GRADE)

OSTEOSARCOMAS

• Localized, low-grade osteosarcomas – The NCCN recommends wide excision

alone; chemotherapy prior to excision is not typically recommended but

could be considered for periosteal lesions

• Low-grade intramedullary and surface osteosarcoma and periosteal

sarcomas with pathological findings of high-grade disease – The NCCN

recommends postoperative chemotherapy [30] ; ESMO-PaedCan-EURACAN

recommends surgery alone for low-grade parosteal osteosarcomas, and

finds no benefit for chemotherapy for periosteal lesions

• Unresectable or incompletely resected osteosarcoma – The NCCN and

ESMO-PaedCan-EURACAN guidelines concur that combined photon/proton

or proton beam radiotherapy for local control is an option](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/osteosarcomaewings-200228154417/85/Osteosarcoma-Ewings-54-320.jpg)

![CHEMOTHERAPY REGIMENS

• For first-line osteosarcoma therapy (primary/neoadjuvant/adjuvant

therapy or for metastatic disease), NCCN recommendations are as

follows [30] :

• Cisplatin and doxorubicin (category 1)

• MAP (high-dose methotrexate, cisplatin, and doxorubicin) (category 1)

• Doxorubicin, cisplatin, ifosfamide, and high-dose methotrexate

• Ifosfamide, cisplatin, and epirubicin](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/osteosarcomaewings-200228154417/85/Osteosarcoma-Ewings-58-320.jpg)

![CHEMOTHERAPY REGIMENS

• For second-line therapy

(relapsed/refractory or metastatic

disease), NCCN recommendations are

as follows [30] :

• Docetaxel and gemcitabine

• Cyclophosphamide and etoposide

• Cyclophosphamide and topotecan

• Gemcitabine

• Ifosfamide (high dose) ± etoposide

• Ifosfamide, carboplatin, and

etoposide

• High-dose methotrexate, etoposide,

and ifosfamide

• Samarium-153 ethylene diamine

tetramethylene phosphonate (SM-

EDTMP) for relapsed or refractory

disease beyond second-line therapy

• Radium-223

• Sorafenib](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/osteosarcomaewings-200228154417/85/Osteosarcoma-Ewings-59-320.jpg)