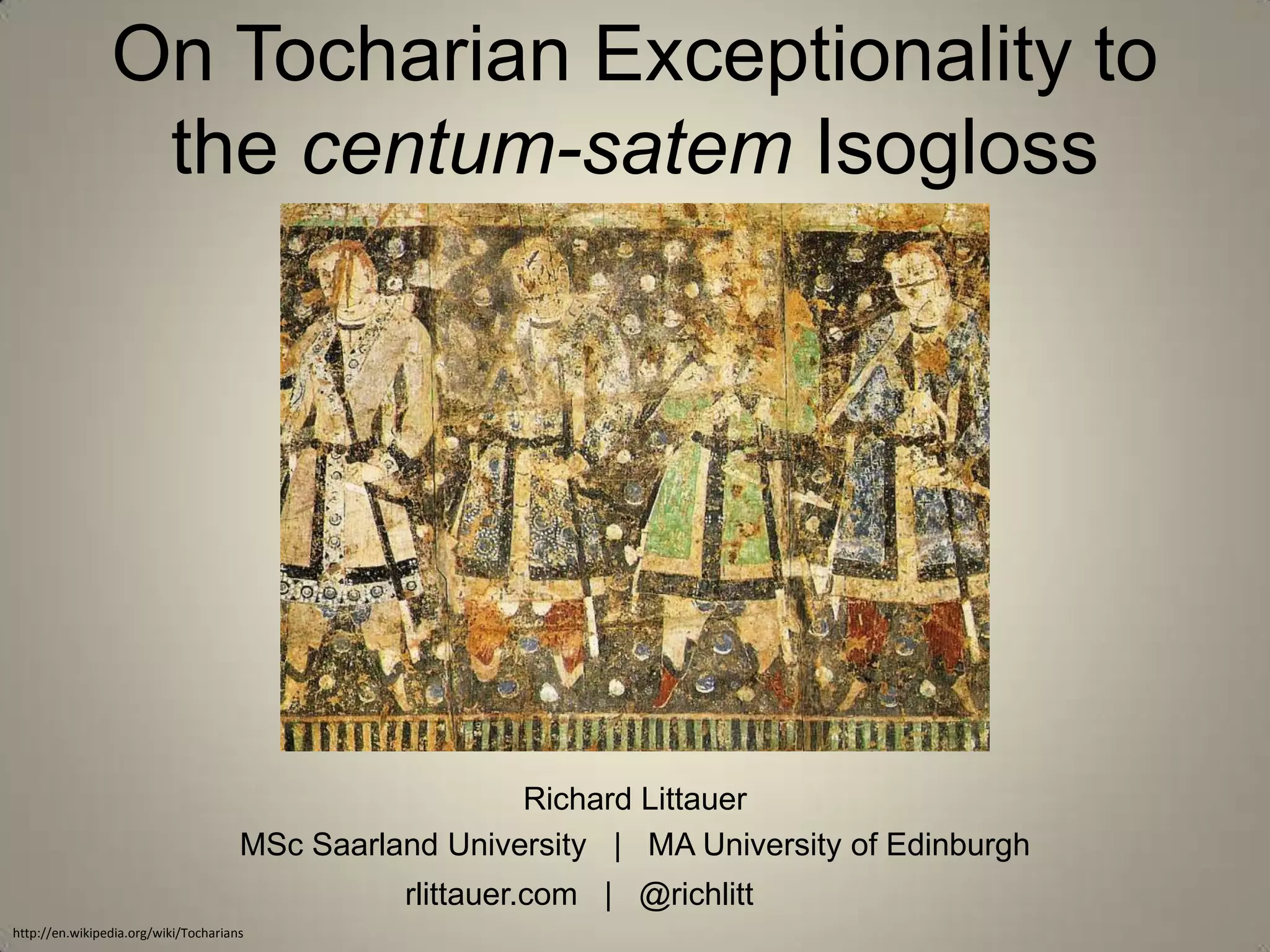

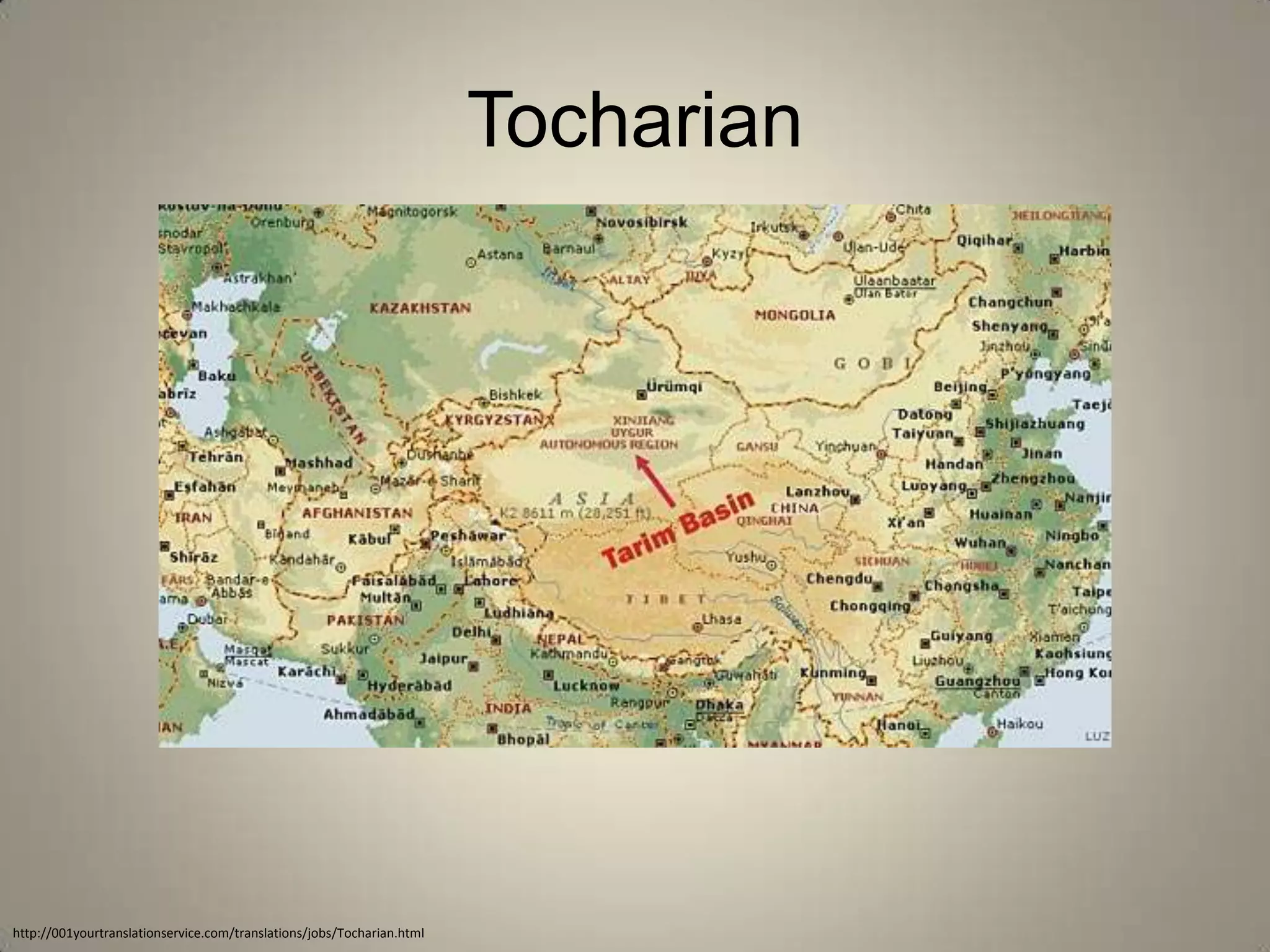

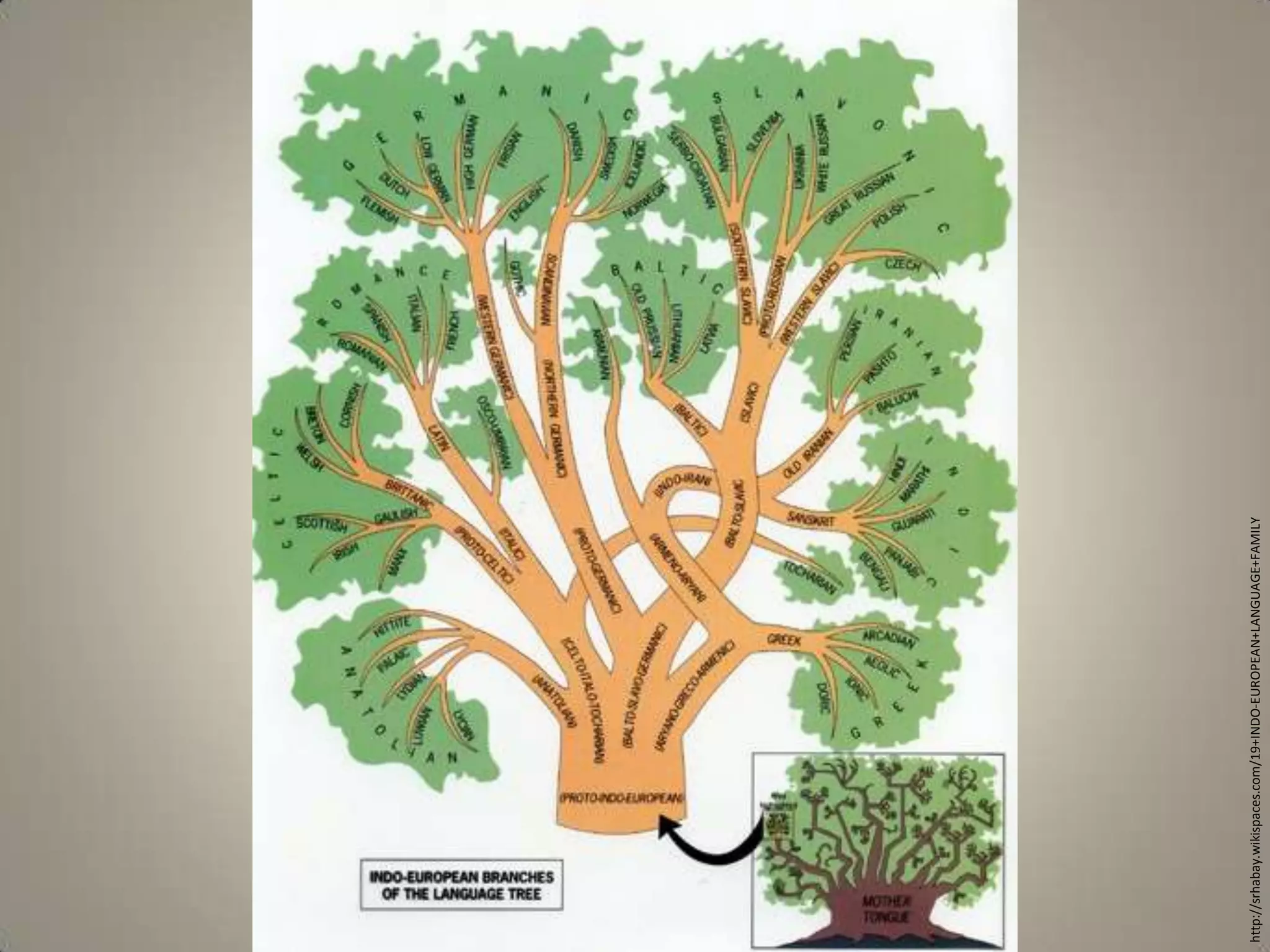

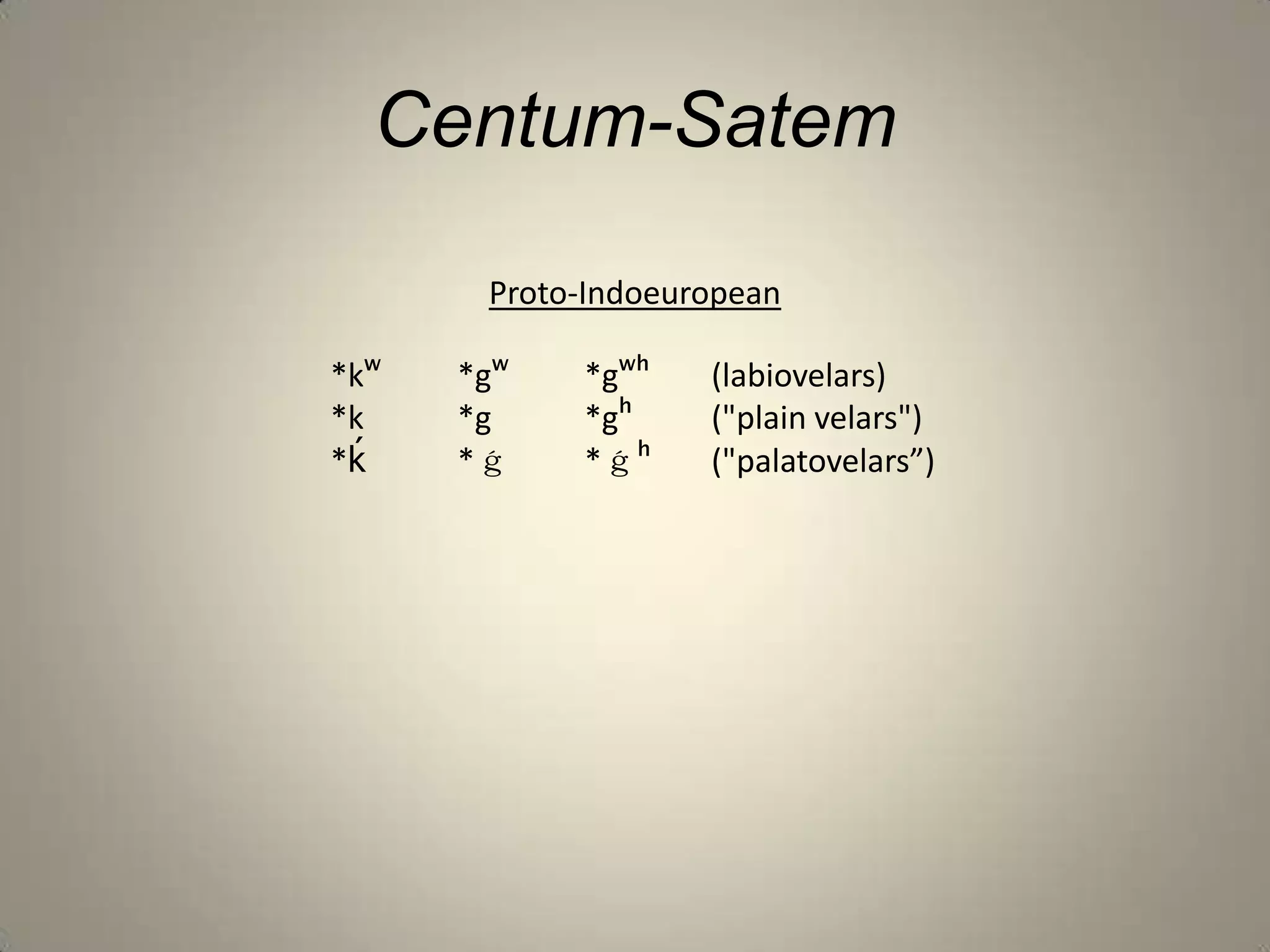

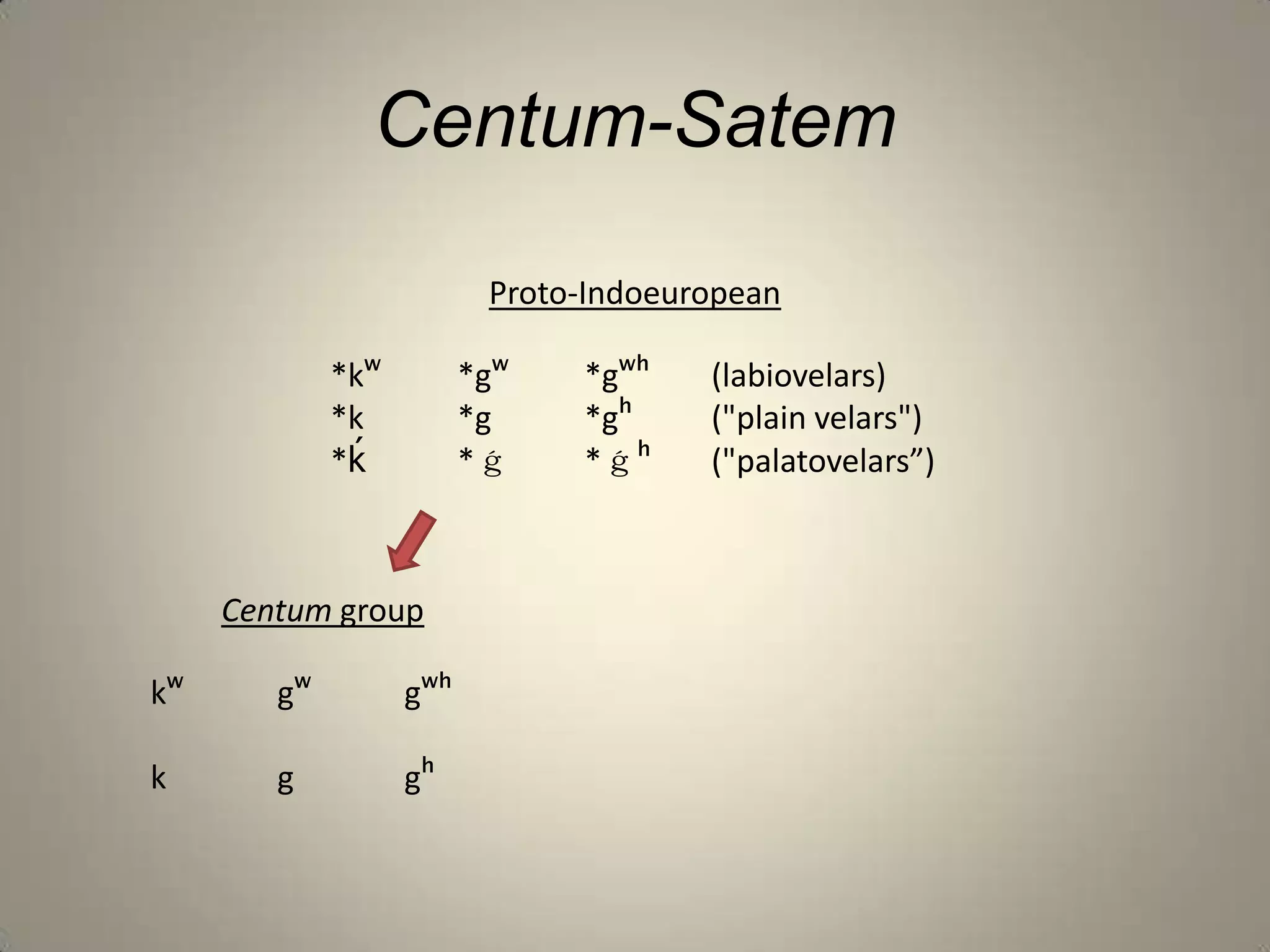

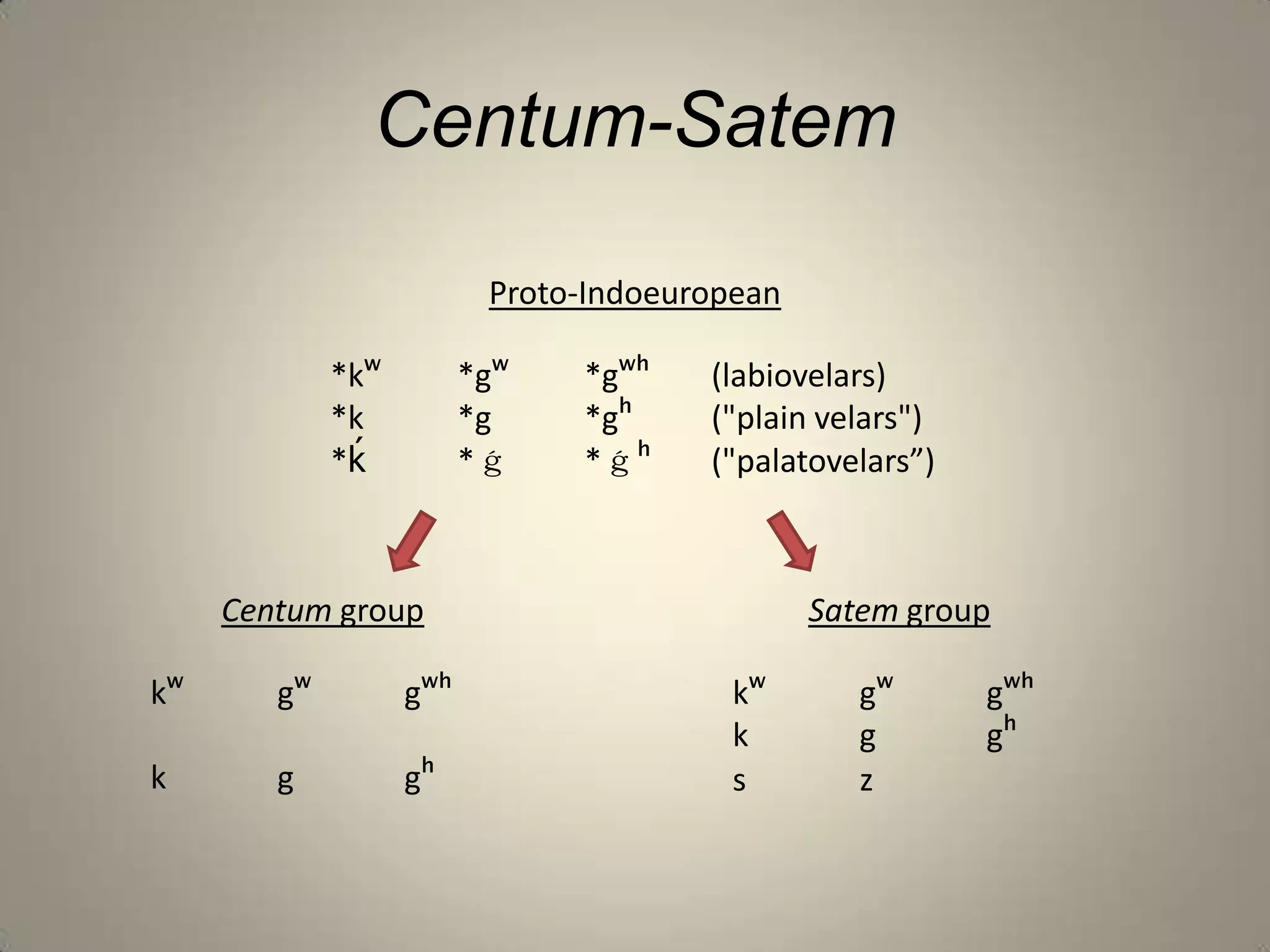

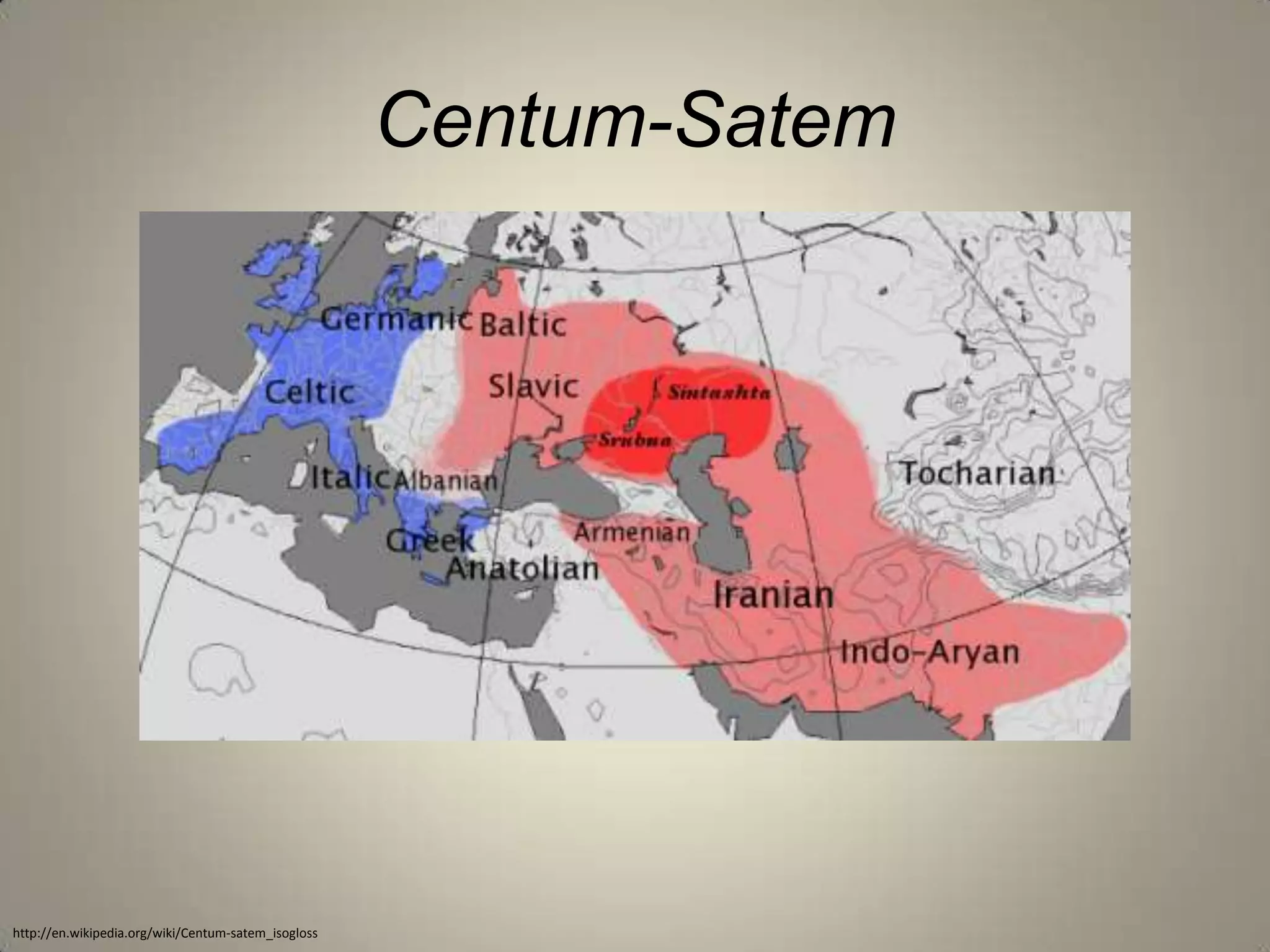

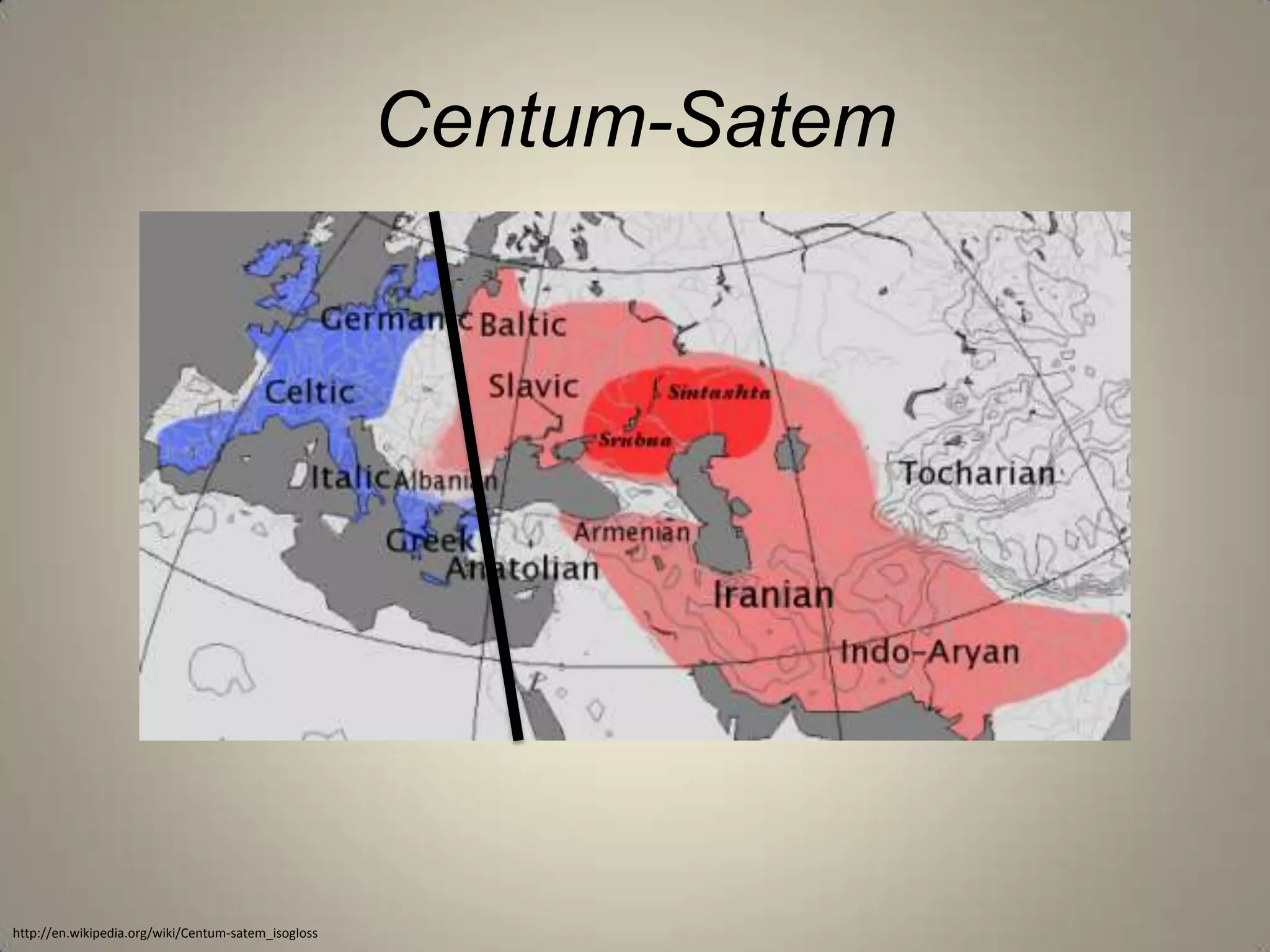

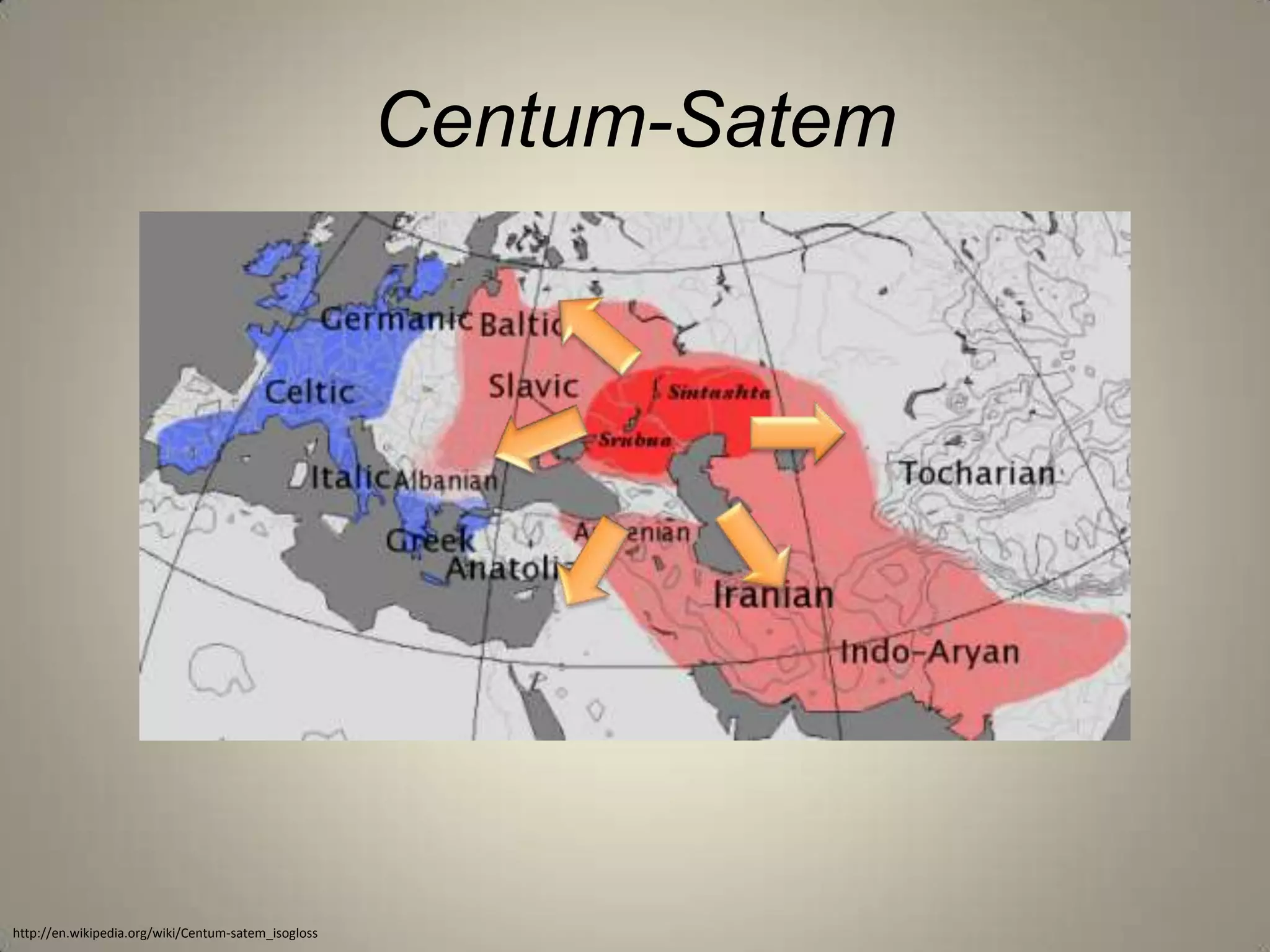

Tocharian was an Indo-European language spoken in ancient times in the Tarim Basin in Central Asia. While most Indo-European languages fall into either the centum or satem category based on their treatment of Proto-Indo-European palatovelars, Tocharian patterns with centum languages but also shows some satem features. This document discusses possible reasons for Tocharian's exceptionality, including language contact influencing its phonology and changes in the size and use of the Tocharian language community over time leading to changes in its phonemic inventory.

![Horizontal Transfer

Could Tocharian have been influenced by non-IE

languages, leading to the merge into [k]?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tocharianulab2012-120423044410-phpapp02/75/On-Tocharian-Exceptionality-to-the-centum-satem-Isogloss-21-2048.jpg)