Historical Linguistics And Endangered Languages Exploring Diversity In Language Change 1st Edition

Historical Linguistics And Endangered Languages Exploring Diversity In Language Change 1st Edition

Historical Linguistics And Endangered Languages Exploring Diversity In Language Change 1st Edition

![1

5

DOI: 10.4324/9780429030390-2

2

Why Is Tone Change Still Poorly

Understood, and How Might

Documentation of Less-

studied

Tone Languages Help?

EricW. Campbell

1. Introduction1

Tone change remains poorly understood. One need only peruse histor-

ical linguistics textbooks (L. Campbell 2013; Crowley and Bowern 2010;

Hock 1991) to find that they include little discussion of tone change or

tonal reconstruction that would guide the historical tonologist in training.

Acknowledging this in footnote #128 of their colorful 177-

page intro-

duction to the Handbook of Historical Linguistics, Janda and Joseph (2003:

173) write,

…we considered offering an apology for this volume’s lack of a spe-

cific chapter on historical tonology. But, when we looked for references

to offer in lieu of such a chapter, we found that, in recent years, there

has been no book-or even article-

length study presenting a general,

consensus-

based overview of the various ways in which tones seem to

arise, split, merge, shift (in quality), move (laterally within a word), and

the like in the world’s languages. [emphasis in original]

One might wonder why this was relegated to a footnote, when

understanding tone is crucial to understanding grammar and language in

general (see e.g.Hyman 2018a),and asYip (2002:1) notes,“by some estimates

as much as 60–

70 per cent of the world’s languages are tonal.”2

That is, for

perhaps a majority of the world’s languages, understanding their historical

phonology entails understanding their historical tonology. While studies in

tonogenesis –the process of non-

tonal languages becoming tonal –have

significantly advanced over the last 65 years (Haudricourt 1954; Hombert

et al. 1979; Kingston 2005, 2011; Matisoff 1973; Mazaudon 1977;Thurgood

2002), our understanding of tone change in already tonal languages trails

behind our understanding of tonogenesis, and it remains distantly behind

our general and typological knowledge about segmental change (but see

e.g. Hyman and Schuh 1974 and also Ratliff 2015). Furthermore, in most

known cases, tonogenesis is linked to segmental change, and perhaps the

most understood type of tone change is tone splitting involving mechanisms

of segmental change similar to those that lead to tonogenesis.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/18429038-250530051145-b9806271/75/Historical-Linguistics-And-Endangered-Languages-Exploring-Diversity-In-Language-Change-1st-Edition-28-2048.jpg)

![16 EricW. Campbell

1

6

Another question, and the one addressed in this paper, is why do we know

so little about tone change? There seem to be several interrelated reasons

for this. First, reconstructions of presumably tonal protolanguages often omit

tone, and without tonal reconstructions we lack the starting points of tonal

changes that could then be identified. A second factor, feeding the first, is

that many descriptions of tone languages include only superficial or even no

description or representation of tone.A third factor,feeding the second,is that

tonal analysis is challenging and linguists may arrive at quite different ana-

lyses of a language’s tone system. Fourth, in some cases tone seems to change

faster or more sporadically than segments, yielding more correspondences to

handle, more changes to unravel, and/

or less-

regular sound correspondences

to deal with; thus, even in language groups where tone analyses exist, tonal

reconstruction may still be limited. Fifth, and finally, even in language groups

in which tonal correspondences are robust,the phonetic nature of the recon-

structable elements may be especially indeterminate ̶that is, more indeter-

minate than reconstructed segments inherently are ̶making it impossible to

accurately characterize any identifiable tonal changes.

While some of the world’s major language families are tonal and some

synchronic and diachronic knowledge of their tone systems exists, many of

the world’s tone languages are not documented, or remain poorly under-

stood, especially in their tonal systems. Endangered tone languages can thus

provide useful or necessary information for understanding tone change –

a challenging and relatively neglected area of historical linguistics –and

thereby advance our understanding of sound change in general.This chapter

explores this issue in several steps. Challenges in tone analysis are discussed

in Section 2. The difficulty and rarity of tonal reconstruction is discussed

in Section 3. A case study from the Chatino languages of Mexico, which

illustrates all of these challenges, is presented in Section 4, and conclusions

are provided in Section 5.

2. Challenges in Tone Analysis

Linguists and speakers of tone languages first approaching a linguistic study

of tone may hear rising pitch contours as falling, or vice versa, or they may

hear high pitch as low, or interpret the same tone inconsistently at different

pitch levels in different instances.Once the challenges of perception and data

gathering are overcome, the challenges of tone analysis remain. Pike (1948:

18–

39) dedicates a whole section of his seminal monograph and field-

guide

to the challenges of tonal analysis, showing that it can be a confusing or

intimidating area of linguistic structure to study.Welmers (1959: 1) laments

that many language students and even linguists “seem to think of tone as a

species of esoteric, inscrutable, and utterly unfortunate accretion character-

istic of underprivileged languages […] and the usual treatment is to ignore

it, in hope that it will go away of itself.”

Welmers’hyperbole aside,it remains a fact that a significant proportion of

linguistic work on tone languages omits tone. Greenberg (1948: 196) notes](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/18429038-250530051145-b9806271/75/Historical-Linguistics-And-Endangered-Languages-Exploring-Diversity-In-Language-Change-1st-Edition-29-2048.jpg)

![Tone change and less-studied tone languages 17

1

7

that a“great majority of descriptions of Bantu languages either disregard tonal

phenomena or list a few pairs of minimal contrasts” without providing any

thorough account. Ross (2005: 5) echoes that in Papua New Guinea “some

descriptions of Highlands languages ignore tone,while others mention it but

give few details, despite the attention drawn to Highlands tone by [Eunice]

Pike (1964).” Omission of tone in linguistic work on tone languages is likely

partly due to the difficulty or uncertainty in how to handle it.

However, even when tone is given its deserved attention, it is not

uncommon to find cases in which linguists arrive at differing analyses of

a tone system. While evaluating prior proposals of genetic relationship

between the Naduhup language family, Kakua-

Nukak, and Puinave, Epps

and Bolaños (2017: 477) note that these Northwest Amazonian “languages

present analytical challenges in their phonological systems,and that the status

of tone, nasalization, and glottalization in particular has led to conflicting

analyses both within and across languages.” Joseph and Burling (2001: 51)

point out that prior analyses of Boro, a Tibeto-

Burman language of North

East India, had posited inventories of two tones, three tones, and even four

tones, and they themselves tentatively settle on a two tone analysis. Then,

in later work (Burling and Joseph 2010: 57), they revise their analysis to

three tones,but concede that the problem remains recalcitrant for Boro even

though the tone systems of other languages of the Bodo-

Garo subgroup are

not problematic.As a further example of differing tone analyses, Munro and

Lopez (1999) analyze San Lucas Quiaviní Zapotec (Otomanguean, Mexico)

as non-

tonal, with pitch differences being due to effects of sequences of

contrastive phonation types. Chávez Peón (2010) agrees that the language

displays phonation contrasts,but argues that it also has four contrastive tones:

High, Low, Falling, and Rising.

So, why might linguists arrive at such differing analyses of tone systems?

And why is tone analysis so challenging? First, tone may consist of other

laryngeal features in combination with pitch (Matisoff 2000: 86; Beam de

Azcona 2004; Mazaudon 2014), as in the Quiaviní Zapotec case, and tone

may interact with quantity (Remijsen 2014), stress (Inkelas and Zec 1988;

Michael 2011),or intonation (Connell and Ladd 1990;Downing and Rialland

2017). Second, in depth tone studies are still few enough that there is yet to

emerge a refined and cohesive typological framework in which to situate

tonal analysis (Section 2.1).Third, no analytic or representational framework

has emerged that can handle the broad typological diversity of tone systems

(Section 2.2).And fourth,the often autosegmental nature of tone may lead to

there being great distance between phonological representations of tone and

its phonetic realization (Section 2.3), opening the way for linguists to arrive

at differing analyses of the system that underlies observed pitch patterns.

2.1. ATypological Framework for DescribingTone?

Pike’s (1948) monograph is usually considered the departing point of

modern tone typology; he roughly classifies tone languages into either the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/18429038-250530051145-b9806271/75/Historical-Linguistics-And-Endangered-Languages-Exploring-Diversity-In-Language-Change-1st-Edition-30-2048.jpg)

![18 EricW. Campbell

1

8

register type common in Africa, the contour type typical of Asia, and over-

lapping types such as the Mixtec and Mazatec varieties (Otomanguean,

Mexico) that he describes in detail. In register tone systems, the basic tonal

contrasts involve mostly level pitch, and pitch contours are often analyzable

as sequences of level tones.In contour tone languages,most contrasts involve

gliding pitch contours that are not fruitfully decomposable into level-

tone

sequences.

The register versus contour typology is one that is based essentially on the

nature of the tonal inventory.Another tone system typology based on inven-

tory is that of Maddieson (2013), who distinguishes between simple tone

systems with a two-

way tonal contrast and complex tone systems with at least

a three-

way tonal contrast.Within register tone systems, another typology

based on inventory is that which classifies tone systems based on how many

tone levels they contrast (Longacre 1952; Maddieson 1978; Edmondson and

Gregerson 1992).

The analysis of a language’s tonal inventory is closely linked to the ana-

lysis of the distribution of tone in the language. For example, tone languages

differ with respect to what serves as the Tone Bearing Unit (TBU), which

is often either the mora or the syllable, but may also be the morpheme,

or the prosodic word as in the Papuan languages Kairi and Kewa (among

others) with so-

called “word-

tone” systems (Donohue 1997; Cahill 2011).

Another distributional difference across tone systems, especially of the

register type, is whether they are privative or not, that is, whether some

TBUs may be underlyingly unspecified for tone (Stevick 1969) and if they

may remain unspecified on the surface as in Chichewa (Myers 1998) and

Zenzontepec Chatino (Campbell 2014). Privativity is of course also rele-

vant for tonal inventory analysis since the absence of tone on some TBUs

can be considered one of the language’s tonal specification contrasts. Pike

(1948: 32) notes that the distribution of tones may be restricted by their

phonetic context or syllable shape (see also Gordon 2001), especially in

languages of the contour type, and that syntagmatic restrictions on tone

sequences within words are more common in register tone languages (Pike

1948: 34).

Ratliff (1992) offers a tone system typology that focuses on the functions

of tone. In her Type A tone languages tone’s function is mostly lexical,

roughly corresponding to the contour type. In her Type B tone languages,

tone also plays a role in inflection and/

or derivation,which is more common

in register type languages. These differences in the functions of tone cor-

relate with other patterns in tonal inventory (larger vs. smaller), distribution

(independence vs. sensitivity to word class), and tonal processes (paradig-

matic vs. syntagmatic), as well as segmental phonotactics (monosyllabic

[Benedict 1948] vs. polysyllabic), and morphological type (analytic vs. syn-

thetic). Interestingly, some Otomanguean languages of Mesoamerica that

would fall into the contour type based on inventory alone are necessarily of

Ratliff’sType B due to the high functional load of grammatical tone, such as

Quiotepec Chinantec (Castillo Martínez 2011), San Juan Quiahije Chatino](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/18429038-250530051145-b9806271/75/Historical-Linguistics-And-Endangered-Languages-Exploring-Diversity-In-Language-Change-1st-Edition-31-2048.jpg)

![20 EricW. Campbell

2

0

2.3. Distance between PhonologicalTones and Phonetic Realizations

Morén and Zsiga (2006: 114) report that in Thai “the realization of some of

the tones changes dramatically from citation form to connected speech”due

to post-

lexical tonal processes. Such distance between lexical tones and their

phonetic implementation presents another challenge to the analyst.A brief

example will illustrate.

Zenzontepec Chatino (czn; Otomanguean, Mexico) has a three-

height,

privative tone system (Campbell 2014; 2016).TheTBU is the mora, and the

inventory of tonal specification contrasts on the mora consists of /H/vs./

M/

vs. Ø, with unspecified moras displaying a relaxed mid-

to-

low falling pitch.

Most words are bimoraic, and aside from words with 2SG person inflec-

tion, they bear one of five basic bimoraic tone melodies: /

MH/

, /

ØM/,

/HM/,/HØ/,and Ø.3

Two primary tonal processes operate both within and

between words in the language: H tone spreading, and H and M downstep.

First,H tone spreads progressively through following unspecified moras until

the end of the intonational phrase. Second, H and M undergo downstep

when following a H tone, whether it is spreading or not. Due to these two

processes, there is significant distance between the basic underlying tone

melodies and their surface pitch realizations:

(1) Zenzontepec Chatino tone melodies and their basic realizations

‘vine’ lūtí /MH/ [‑ ˉ] M target followed by H target

‘river’ kelā /

ØM/ [˗ ‑] level, or slight declination followed

by M target

‘yellow’ nkát

͡ ʃi /HM/ [ˉ ˍ] H target followed by downstepped M

‘six’ súkʷa /HØ/ [ˉ ˉ] initial H target, spreads through

second mora

‘tortilla’ tʃaha Ø [‑ ˍ] mid-

to-

low pitch, no tonal targets,

declination

If one were to analyze the Zenzontepec Chatino tone system based solely

on the surface pitch of isolated words, the basic word melodies would be

/

MH,MM,HL,HH,ML/and the tonal processes of spreading and downstep

observable between words would be difficult to explain and hard to recon-

cile with such an inventory.It is only by considering the tonal inventory,dis-

tribution, and processes all together that the nature of the system as a whole

becomes clear.This is crucial because it is the basic tonal contrasts (or tone

melody contrasts) –and not merely their surface forms –that are ultimately

compared in order to reconstruct tone and understand tone change.

3. Tonal Reconstruction

Understanding tone change is dependent on identifying individual tone

changes,and identifying tone changes is mutually dependent on tonal recon-

struction.That is,one identifies sound changes by reconstructing sounds of a](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/18429038-250530051145-b9806271/75/Historical-Linguistics-And-Endangered-Languages-Exploring-Diversity-In-Language-Change-1st-Edition-33-2048.jpg)

![22 EricW. Campbell

2

2

of Mixtec.” In Asia as well, Morey (2005: 146) notes that the “most salient

differences between languages in theTai family are often found in their tonal

systems, in terms of the number, distribution and realisation of those tones,”

and Ratliff (2015: 249) echoes this sentiment, stating that “tones in Asian

languages tend to change rapidly and in unexpected ways.”

Before moving on,it is important to point out that the perceived propen-

sity for tones to change quickly involves an entirely different phenomenon

from what is discussed in other literature as a high degree of diachronic

“stability” of tone as a typological feature (Nichols 1995; Wichmann and

Holman 2009). In the latter studies, what is referred to is the stability of

tonality, that is, the presence or absence of tone in languages, and not the sta-

bility of tones themselves or the nature or rates of tone change per se.

3.2. Phonetic Divergence

Another of the several interrelated factors contributing to the difficulty

in tonal reconstruction is that cognate tones often display quite distant or

even opposite phonetic values. Strecker (1979: 171) notes that while “the

phonetics of the vowel and consonant correspondences amongTai languages

are –for the most part –fairly straightforward, the phonetics of the tonal

correspondences are very diverse and puzzling.”Consider Strecker’s example

of the divergent tones in the cognate words for ‘paddy field’ across a sample

of Tai languages in (2), which display all heights of level tones, falling tones,

a rising tone, and some with accompanying glottalization:

(2) Reflexes of proto-

TaiTone A when following a voiced initial:‘paddy

field’

naː ˥˨ 52 High falling Khamti (Mān Chong

Kham locality)

naː �’ 53’ High falling, glottalized Tho (That-

Khe locality)

naː ˧˩ 31 Mid falling Tho (Lungchow locality)

naː ˧˦ 334 Mid rising Kam Mųang (Chengrāi

locality)

naː ˥ 55 High level Shan (Hsi Paw locality)

naː ˦ʔ 44ʔ High-

mid level, glottal

stop

White Tai (Lai Chau

locality)

naː ˧ 33 Mid level (Xieng Khouang locality)

naː ˩ 11 Low level Pu-i (Lu-jung locality)

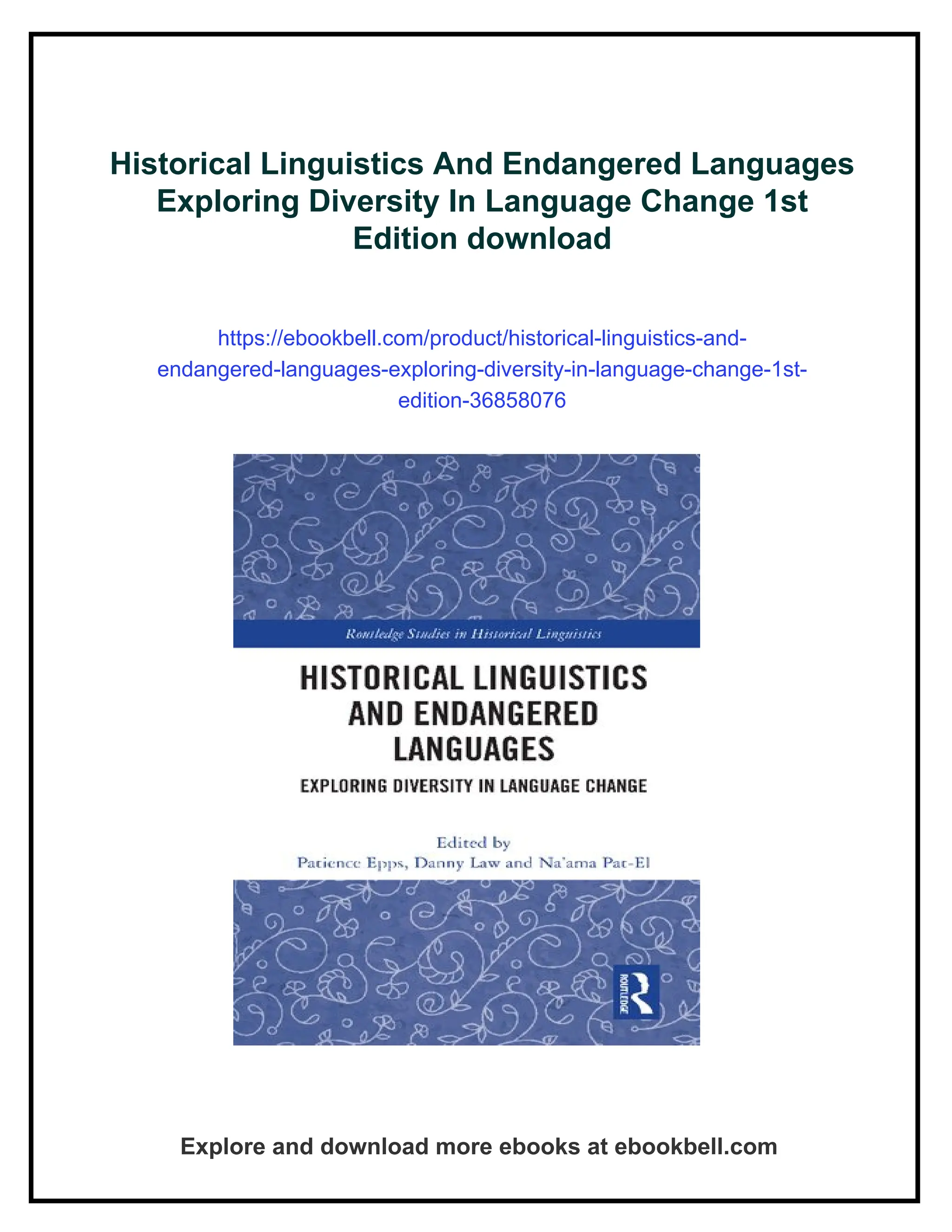

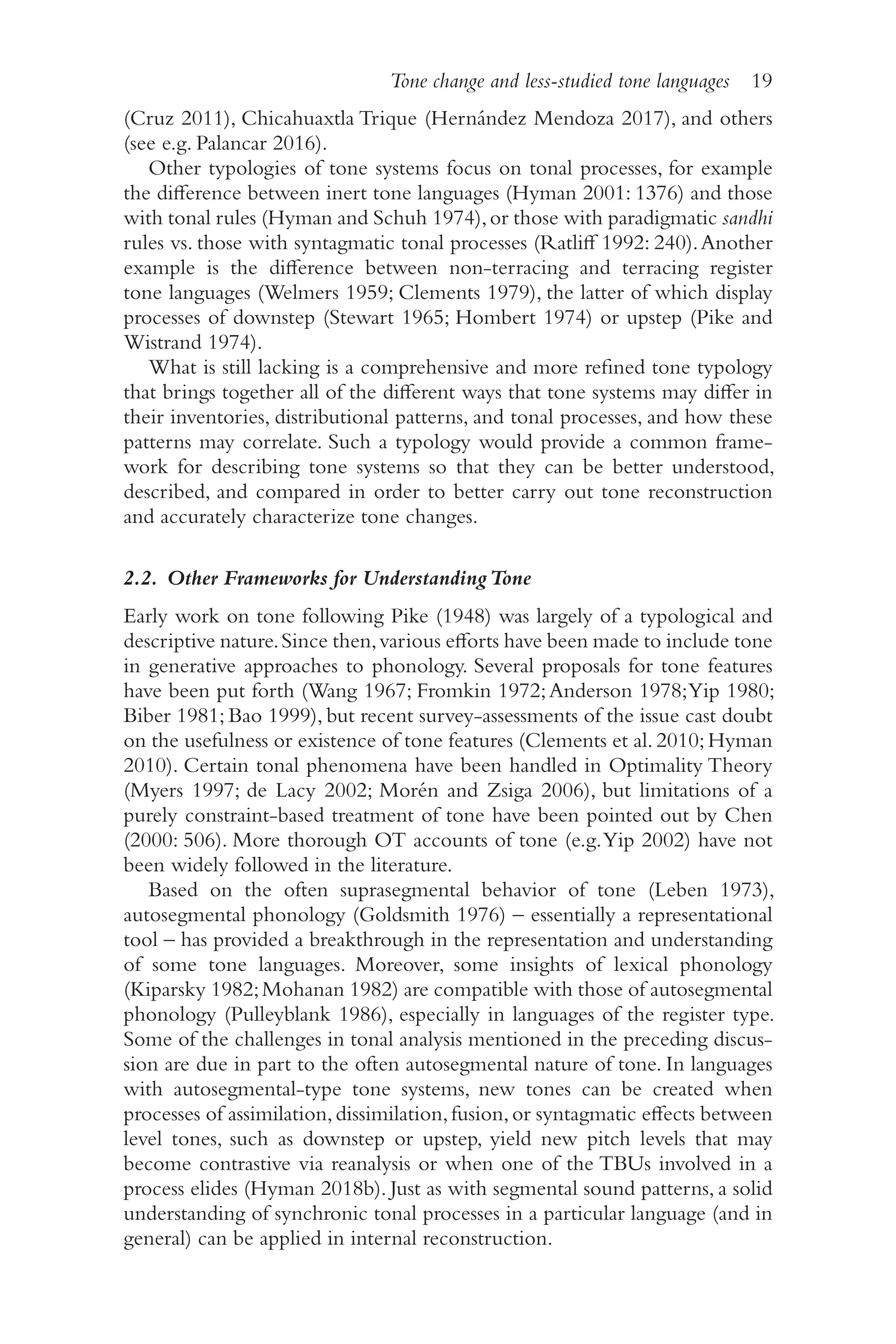

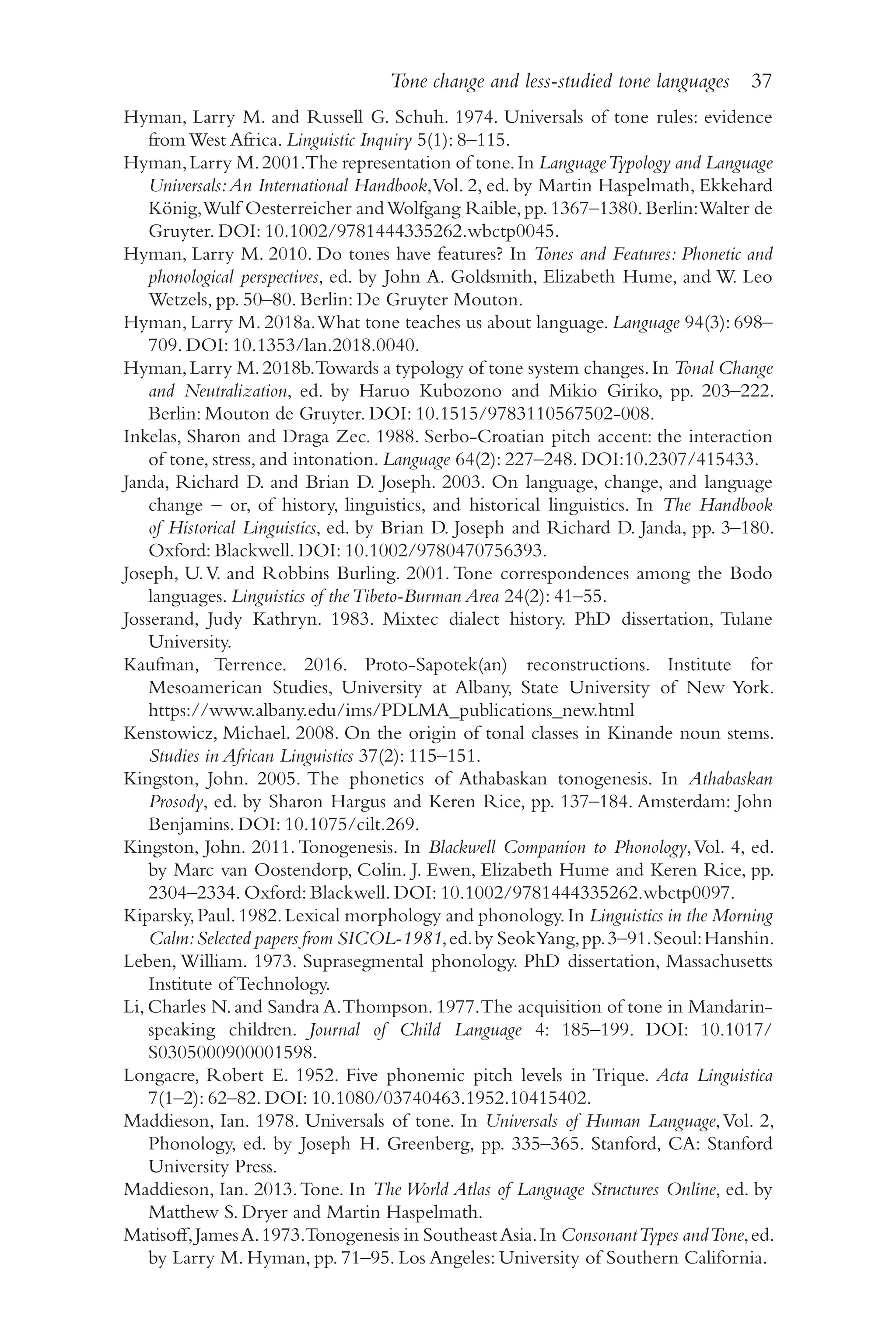

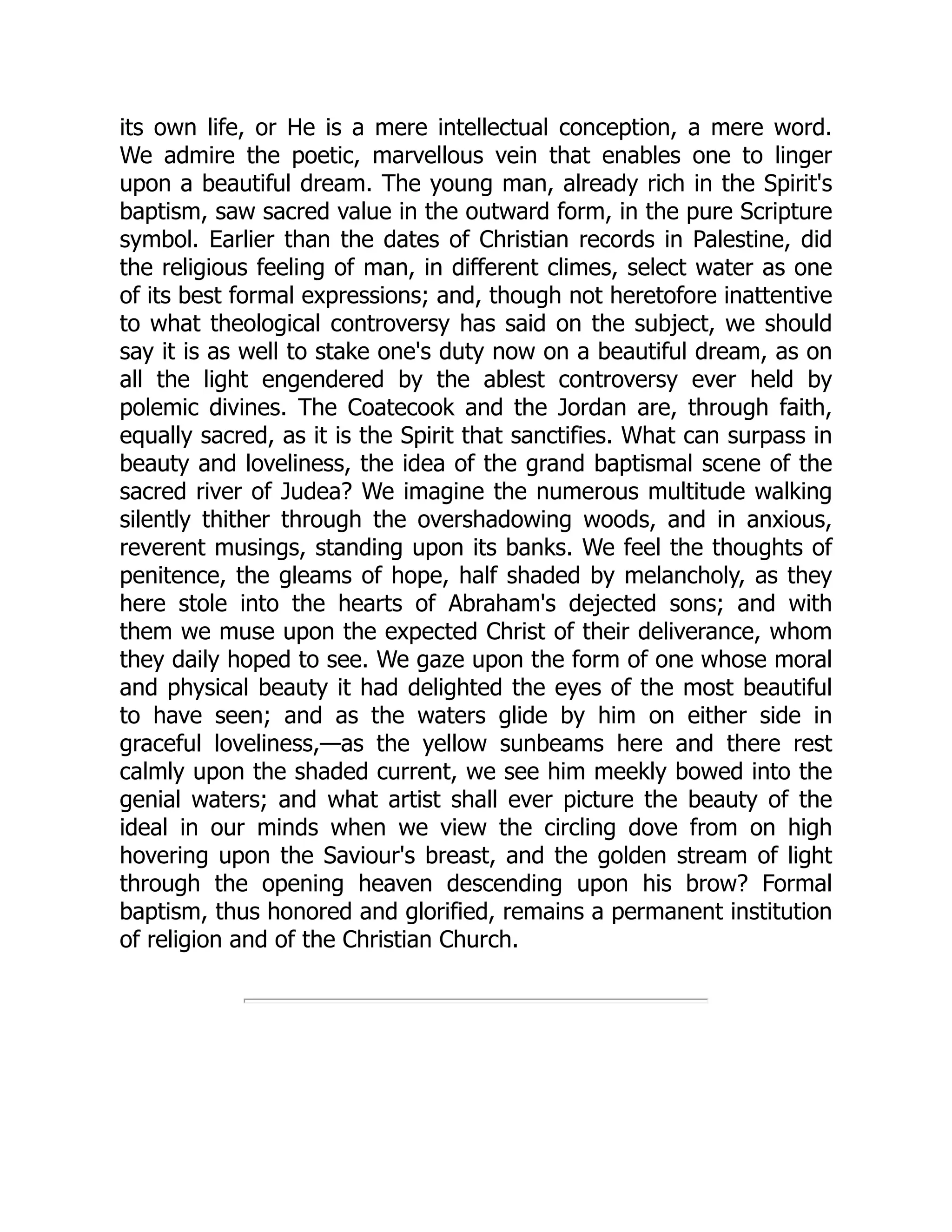

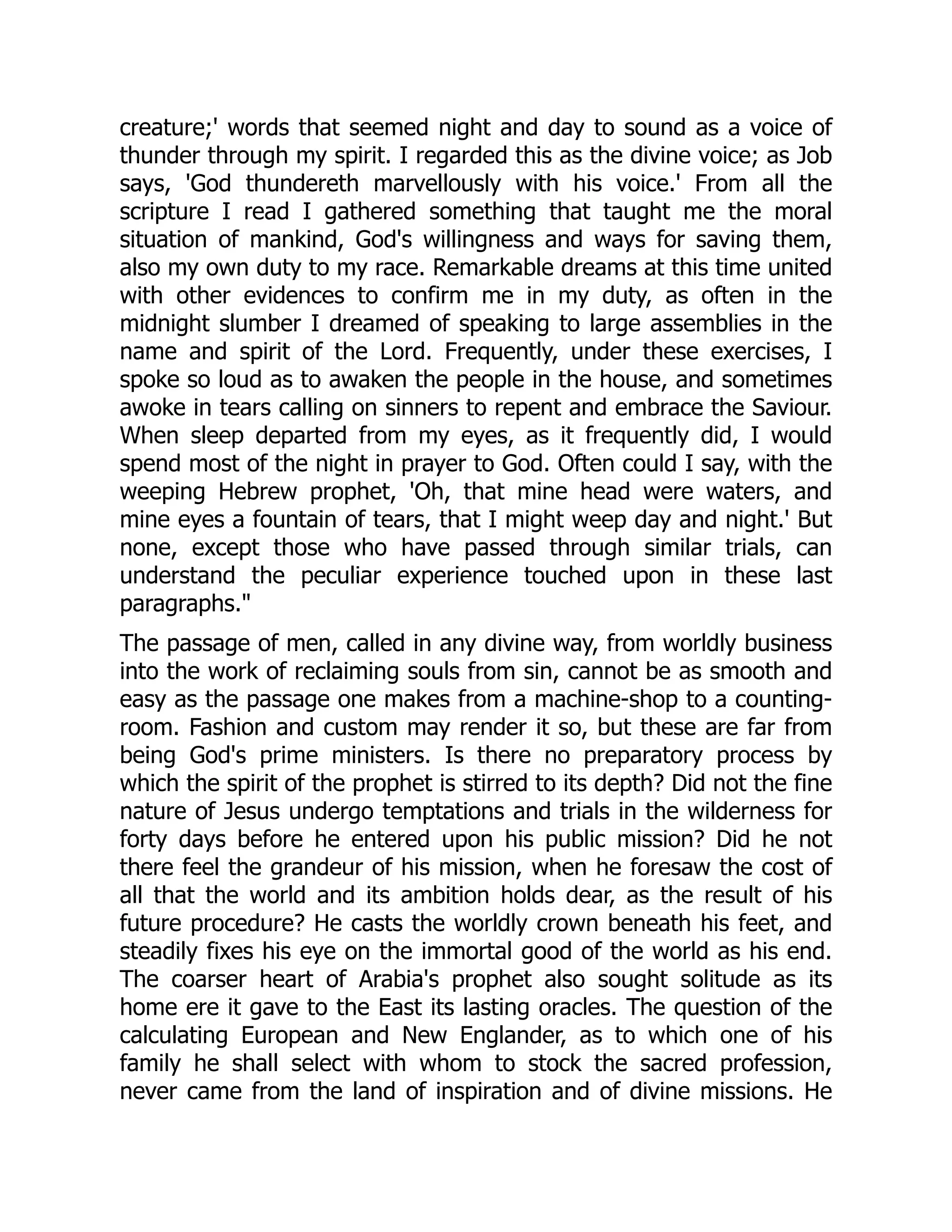

Despite the puzzling phonetics of Tai tonal correspondences, the regularity

of the correspondences is robust (Morey 2005: 151). Due to the regularity

of Tai tonal correspondences and advances in the understanding of Tai his-

torical tonology, for half a century Tai tonologists have enjoyed Gedney’s

(1989 [1972]) Tai “tone box” for outlining the tone system of a previously

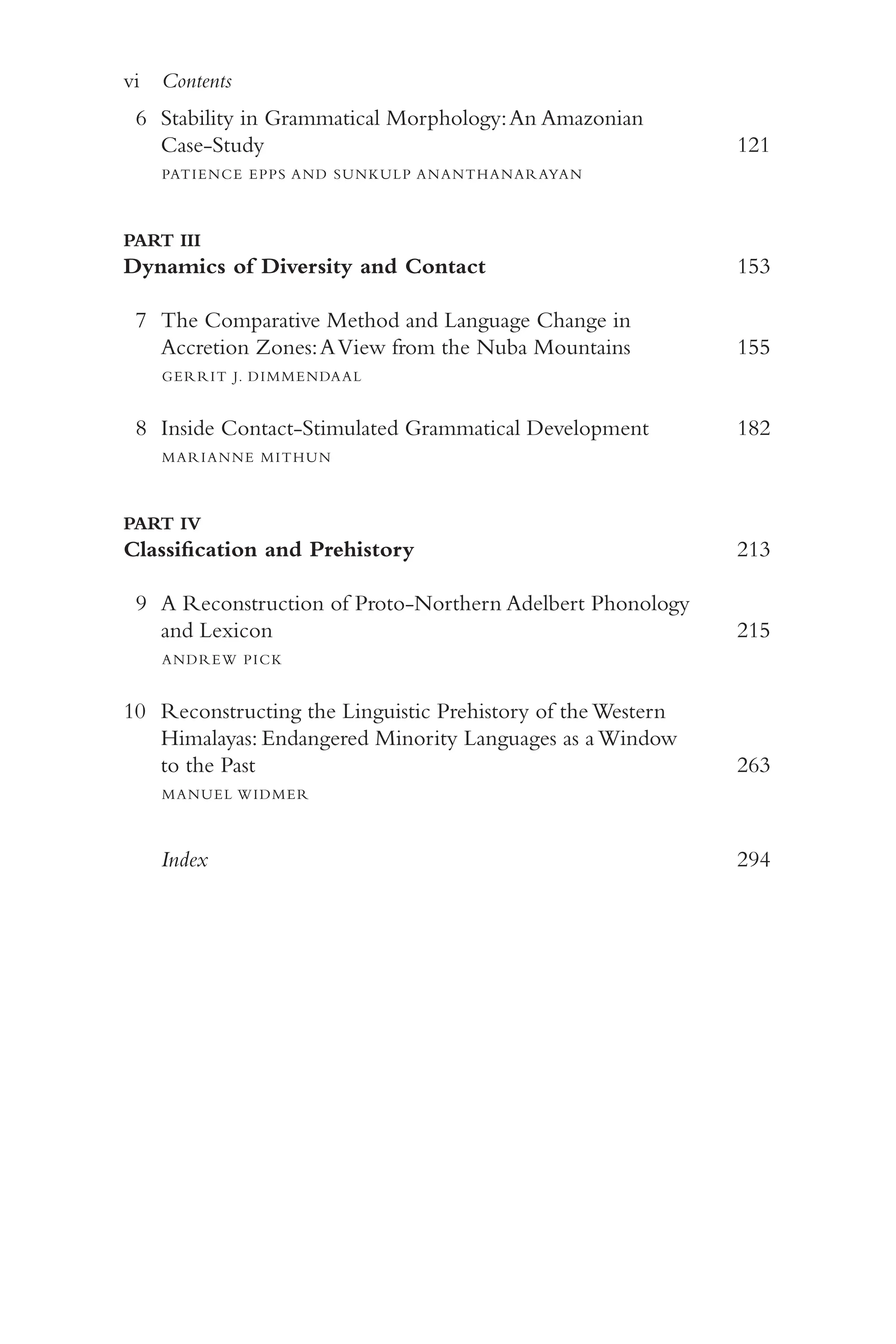

undescribed variety (Figure 2.1).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/18429038-250530051145-b9806271/75/Historical-Linguistics-And-Endangered-Languages-Exploring-Diversity-In-Language-Change-1st-Edition-35-2048.jpg)

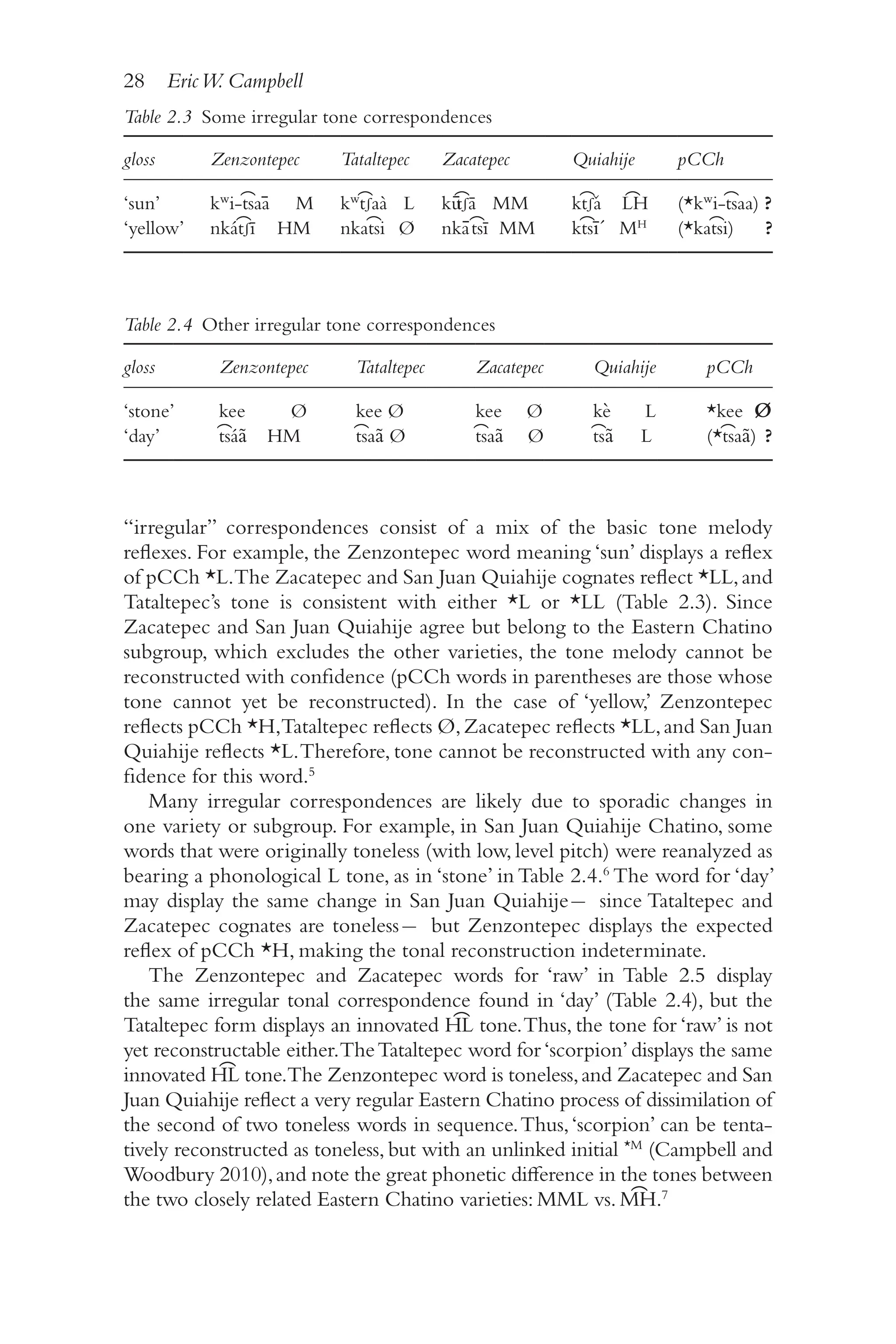

![Tone change and less-studied tone languages 23

2

3

Sets of several words have been established for probing the various

outcomes of the proto-

Tai tones depending on the laryngeal features of the

initial consonants at the time of tonal splits. However, due to the drastically

different phonetics of cognate tones across varieties –even closely related

varieties –the phonetic nature of the proto-

Tai tones is indeterminate.

Because of this, the proto-

Tai tones are referred to by the arbitrary letters A,

B, C, and D. Thus, while Tai historical tonology is relatively advanced, it

remains difficult to precisely characterize particular Tai tone changes that

would contribute to a general typology of tone change.

Recent lines of research, however, have produced some promising results

for understanding tone change, at least for languages of East and Southeast

Asia, over short time periods. Recordings and pitch analysis of Bangkok

Thai exist from a little over a century ago (Bradley 1911), and Zhu et al.

(2015, cited in Yang Xu 2019) observe that Thai tones have changed in

a “clockwise” fashion since then: mid-

falling high-

falling high-

level

mid-

rising falling-

rising low-

level mid-

falling. Pittayaporn (2018)

attributes this directionality to phonetic variation due to articulatory delays

in reaching tonal targets and contour reduction in connected speech, from

which structural (systemic) forces privilege certain variants for reanalysis.

Yang Xu (2019) find similar patterns in synchronic variation in a sample

of 52 Asian tone languages (from the Tai-

Kadai, Hmong-

Mien, Sinitic, and

Tibeto-

Burman families), and argue that truncation of pitch trajectories in

natural speech also plays a role.It is important to note,however,that the level

tones in Bangkok Thai have remained relatively stable (Pittayaporn 2018),

and the mechanisms of change described in these studies may apply mostly

to contour tones.

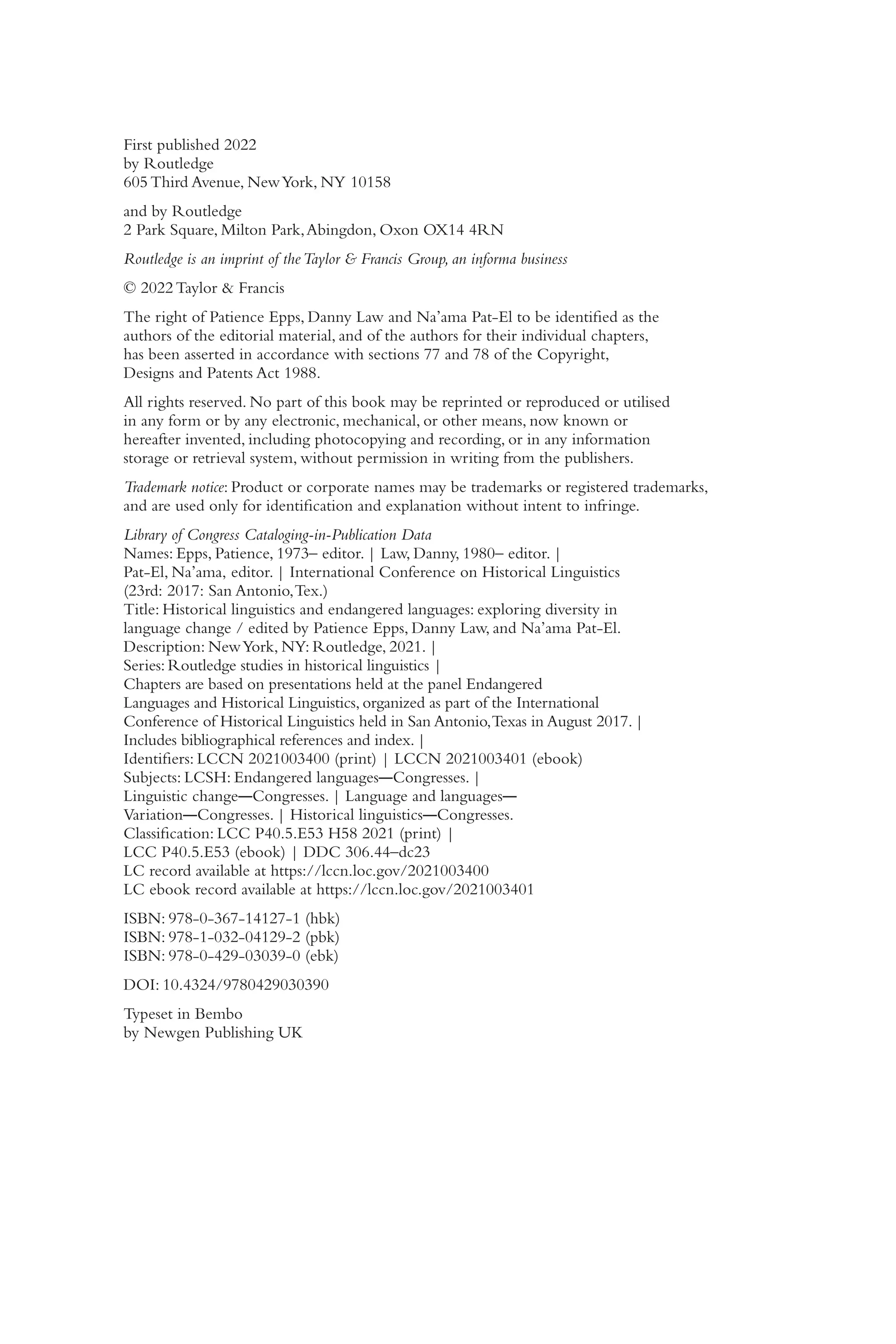

1

Voiceless friction sounds,

*s, hm, ph, etc.

Voiceless unaspirated

stops, *p, etc.

Glottal, *ʔ, ʔb, etc.

Initials

at time of

tonal splits

Voiced, *b, m, l, z, etc.

5 9 13 17

A B C

Proto-Tai Tones

D-short D-long

2 6 10 14 18

3 7 11 15 19

4

Smooth Syllables Checked Syllables

8 12 16 20

Figure 2.1

Gedney’s (1989[1972]: 202) Tai tone box](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/18429038-250530051145-b9806271/75/Historical-Linguistics-And-Endangered-Languages-Exploring-Diversity-In-Language-Change-1st-Edition-36-2048.jpg)

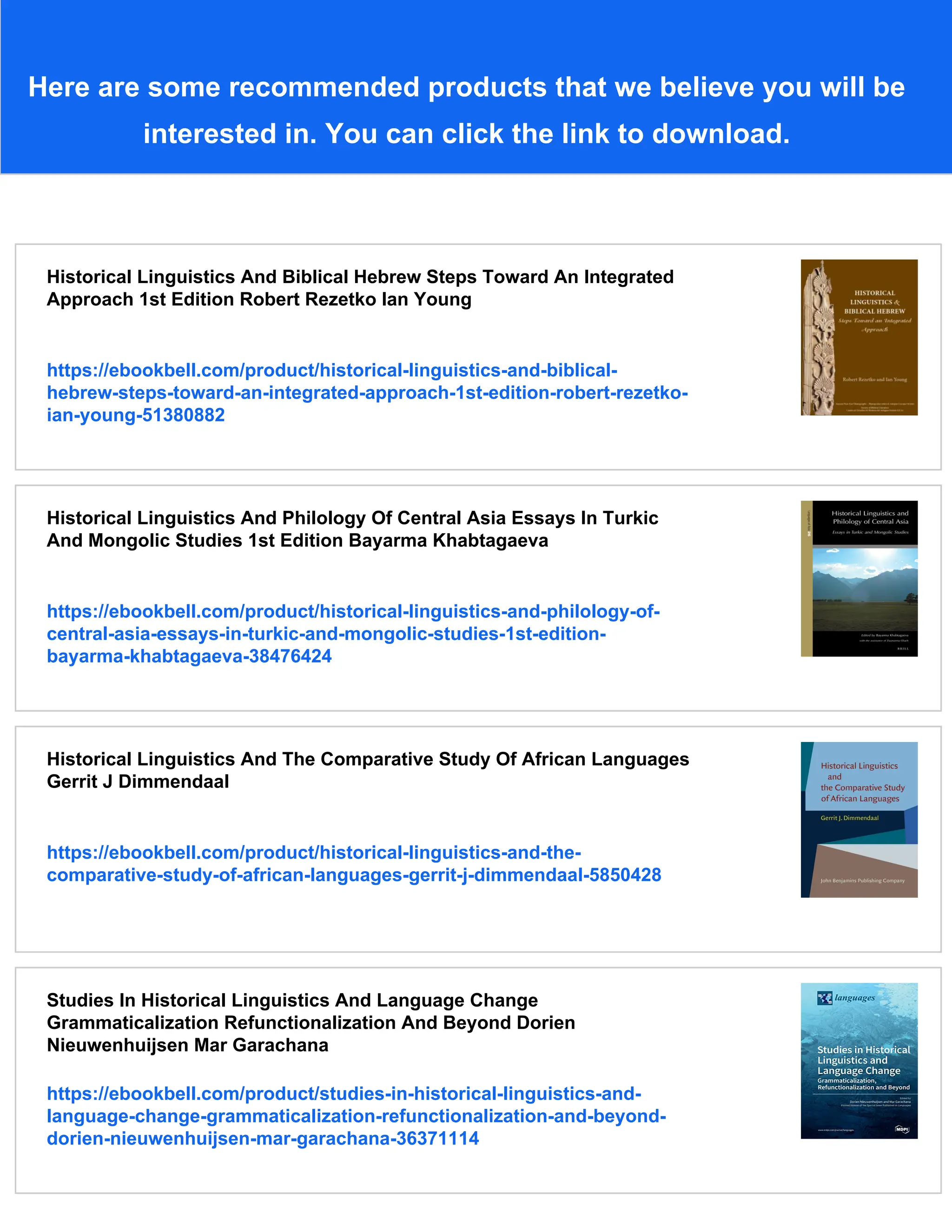

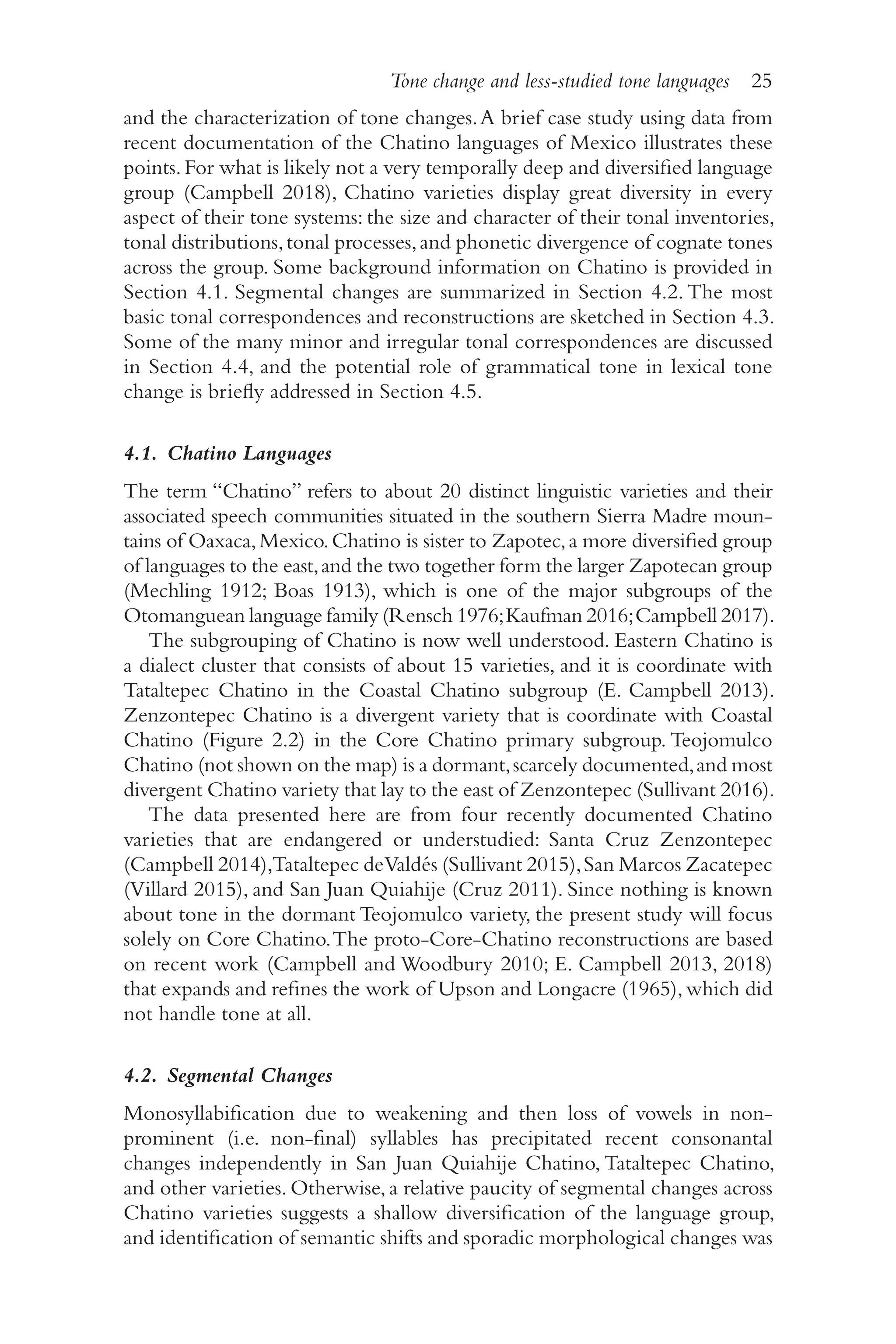

![26 EricW. Campbell

2

6

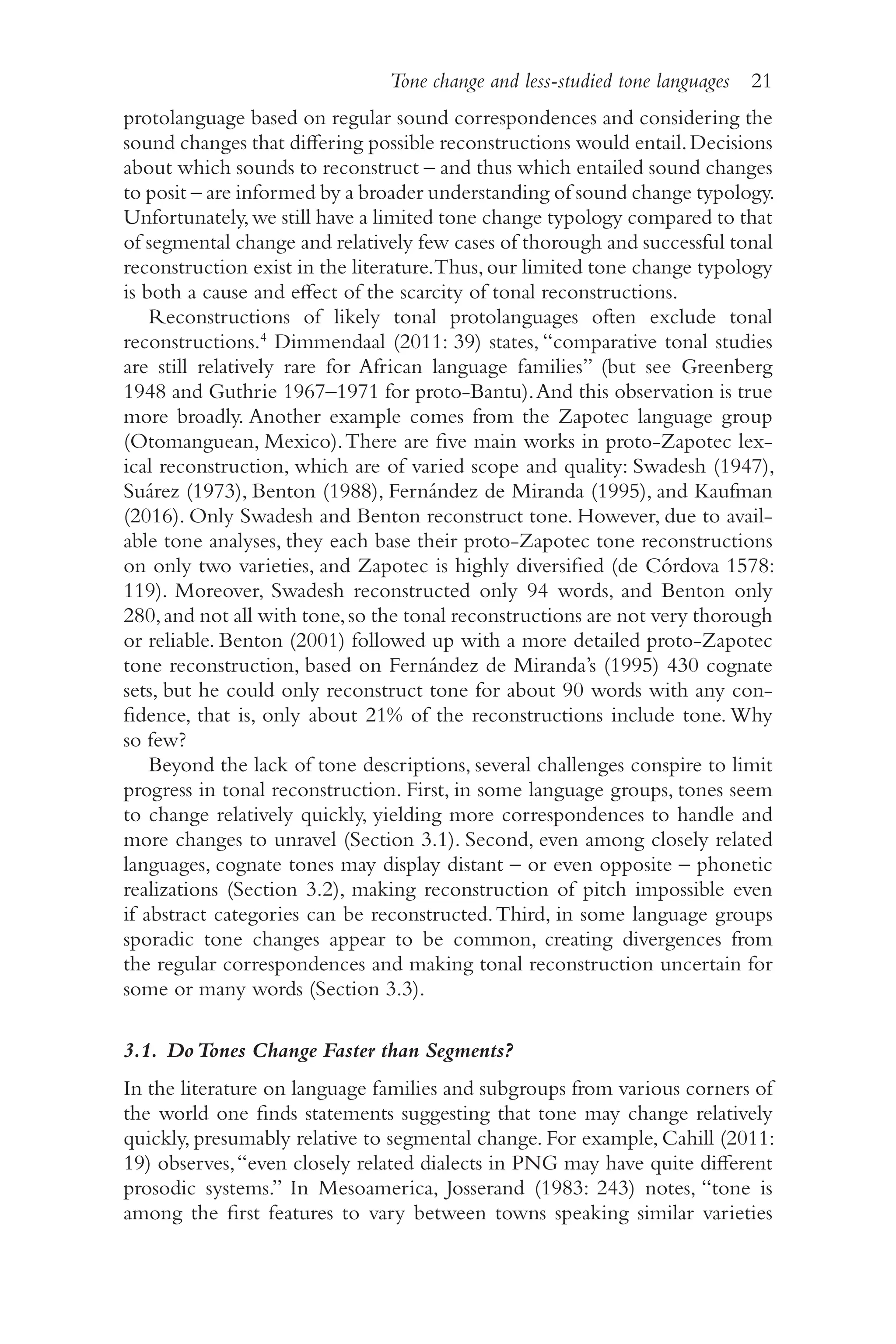

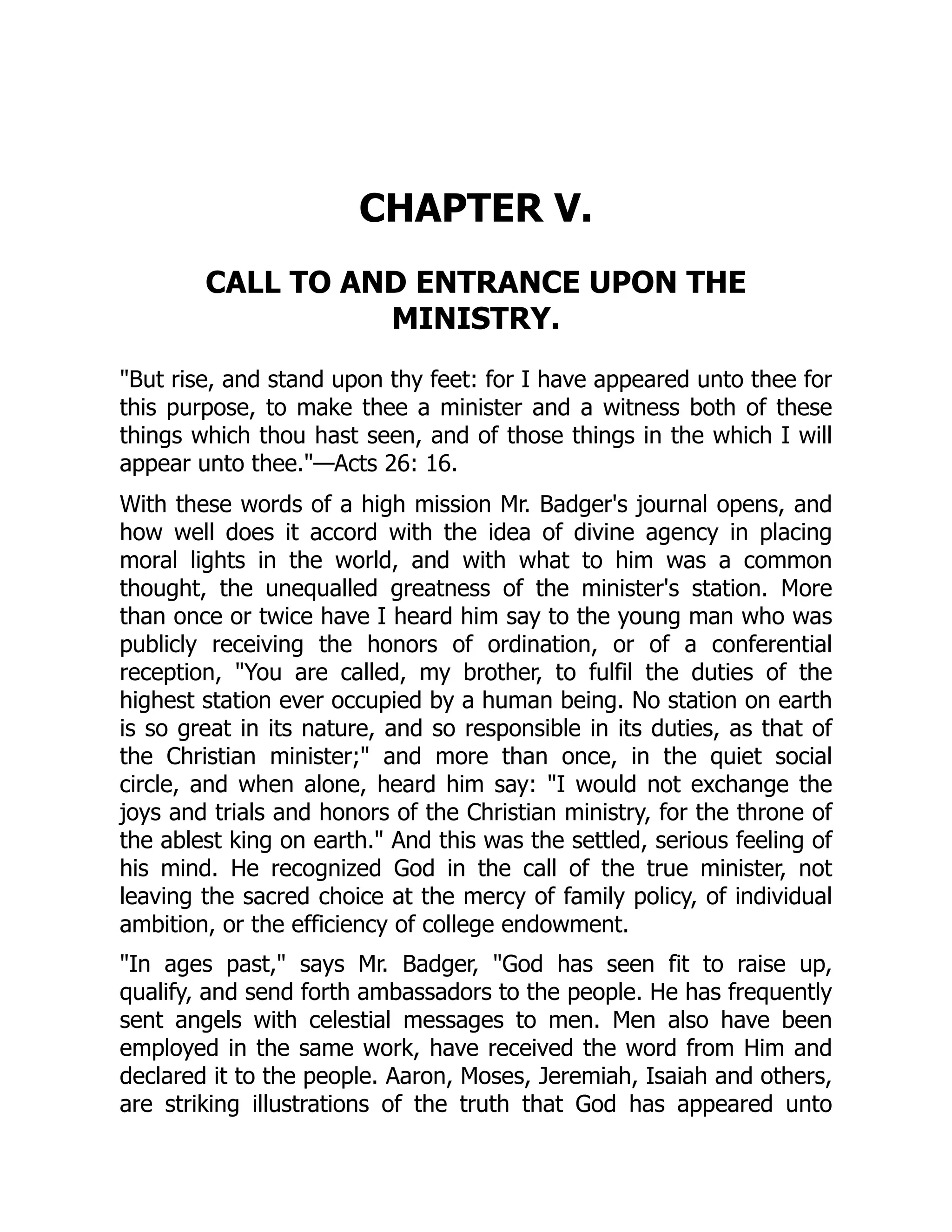

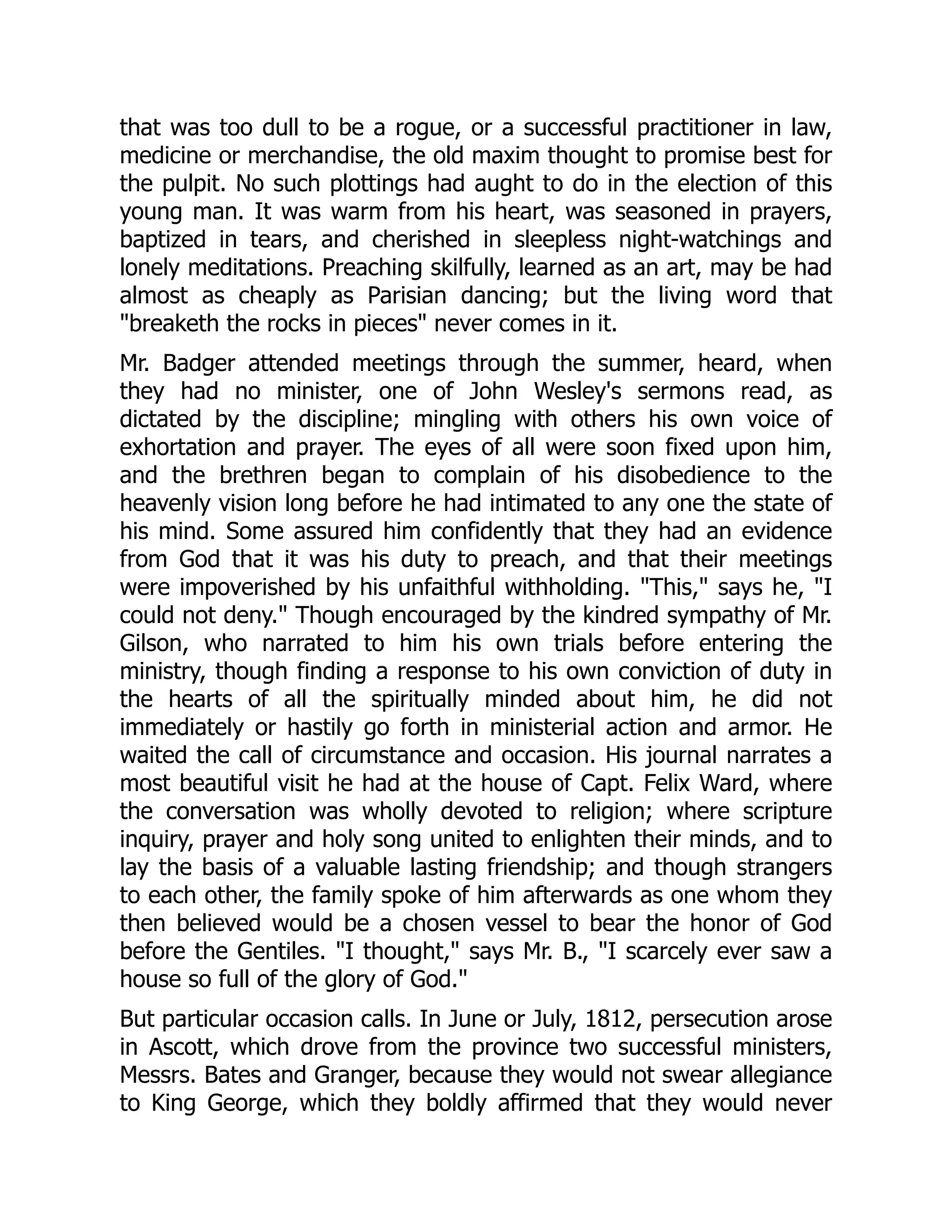

necessary in order to establish subgrouping based on shared innovations (E.

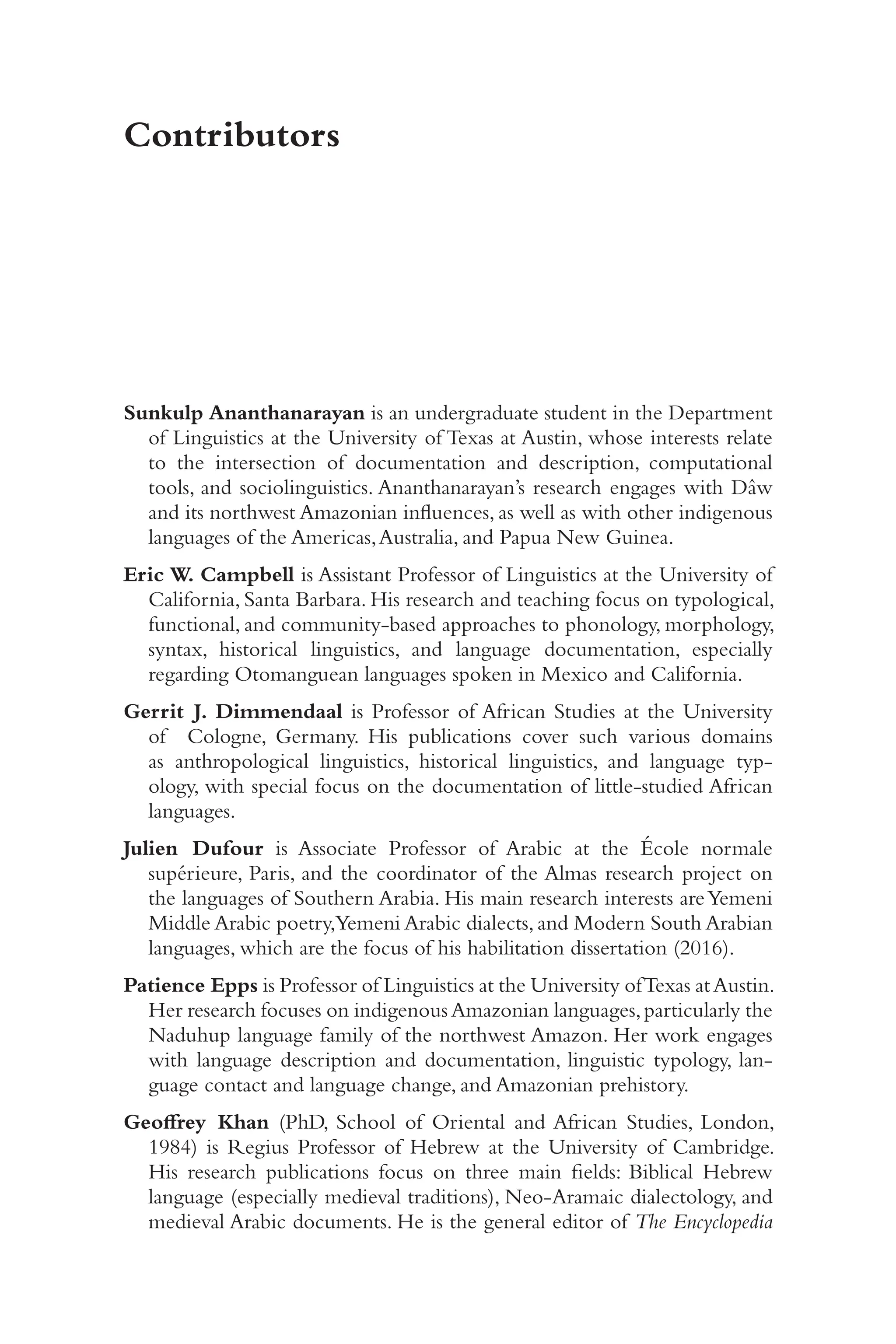

Campbell 2013).The main regular segmental changes that have occurred in

Core Chatino varieties are listed in Table 2.1.

Since relatively few segmental changes have occurred in Chatino var-

ieties, segmental correspondences are phonetically close and quite regular, as

can be seen in the cognate sets and reconstructions throughout the following

presentation.

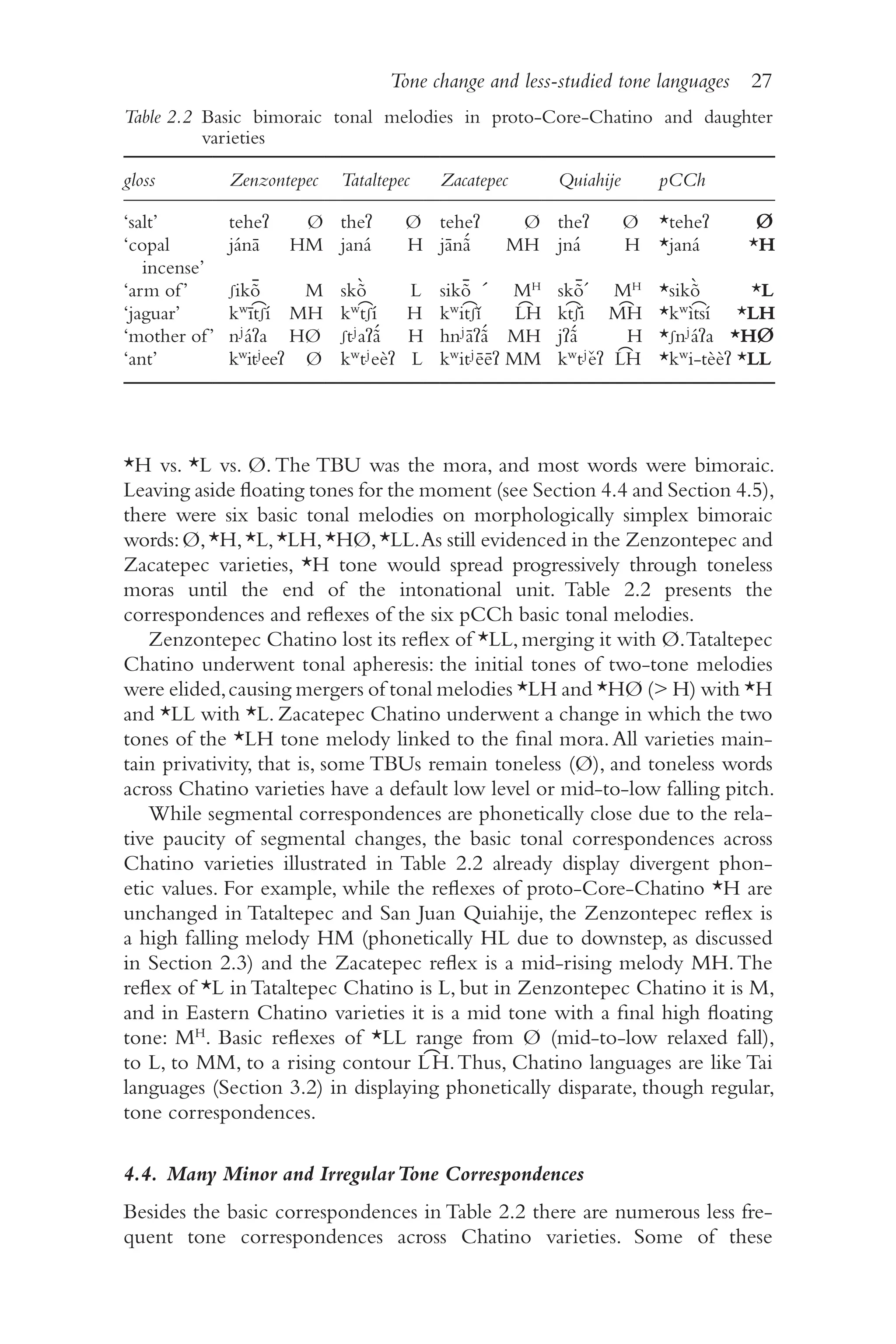

4.3. BasicTonal Correspondences, Reconstructions, and Changes

Preliminary tonal reconstruction (Campbell andWoodbury 2010) posits that

proto-

Core-

Chatino (pCCh) had a three-

way tonal specification contrast:

ZEN

Coastal Chatino

Eastern Chatino

Chatino Language Groupings

Panixtlahuaca

YAI

TEO

SJQ

ZAC

TAT

Panixtlahuaca

YAI

TEO

SJQ

ZAC

TAT

ZEN

Puerto Escondido

Río Grande

N

Pacific Ocean

Río Atoyac

R

í

o

V

e

r

d

e

MIXTEC

M

I

X

T

E

C

Figure 2.2

Chatino varieties and their subgrouping (E. Campbell 2013)

Table 2.1

Regular segmental changes in four Chatino varieties

Regular segmental

changes

Zenzontepec Tataltepec Zacatepec Quiahije

*t

͡ s, *s t

͡ ʃ, ʃ / __ i ✓ ― ― ―

*t

͡ s, *s t

͡ ʃ, ʃ /i _

_ ― ✓ ✓ ✓

*e i /_

_(C)CV# ― ― ✓ ✓

C[+cor] Cʲ /e _

_ ― ✓ ― ―

*V Ø / __ (C)CV ― ✓ ― ✓](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/18429038-250530051145-b9806271/75/Historical-Linguistics-And-Endangered-Languages-Exploring-Diversity-In-Language-Change-1st-Edition-39-2048.jpg)

![Tone change and less-studied tone languages 33

3

3

broader understanding of language change. Since likely more than half of

the world’s languages are tonal, our limited understanding of tone change is

a glaring lacuna. Much more historical tonology work is needed in Africa,

the Americas, New Guinea, and elsewhere, in order to begin to fill this gap,

and further documentation of endangered or less-

studied tone languages is

necessary as a foundation for further historical work.

Finally, and importantly, what does all of this mean for communities and

speakers of less-

studied or endangered tone languages? First, people gener-

ally value and take interest in the deeper cultural and social histories of their

communities,which comparative reconstruction,subgrouping,and language

and prehistory can shed unique light on.As Gedney (1989[1972]:191) notes,

“the most useful criterion for dialect boundaries within the Tai-

speaking

area is perhaps that of tonal systems.”Second,in-

depth knowledge about the

tone systems of closely related languages and their tonal correspondences

can facilitate community-

based literacy development and unite efforts across

multiple varieties and communities (Cruz and Woodbury 2014). Such lan-

guage activism can open up new domains and new media for language use

and help promote language maintenance and multi-

literacy.

Notes

1 Sincere thanks to Pattie Epps, Na’ama Pat-

El, and Danny Law for the invi-

tation to develop this work for the 2017 ICHL meeting in San Antonio,

Texas, and for their work as editors of this volume. The paper was substan-

tially improved with feedback from Tony Woodbury at several stages, feedback

from the Routledge series editor, and discussion by the audience at ICHL.

Thanks to Tranquilino Cavero Ramírez for his long-

standing collaboration on

documenting Zenzontepec Chatino,and thanks to Emiliana Cruz,Hilaria Cruz,

Ryan Sullivant, StéphanieVillard, and Tony Woodbury for sharing the data and

knowledge they have created with many Chatino collaborators.Any remaining

errors are the author’s sole responsibility.

2 A more conservative and likewise tentative estimate of the percentage of the

world’s languages that may be tonal is offered by Maddieson (2013):“Of the 526

languages included in the data used for this chapter, 306 (58.2%) are classified

as non-

tonal. This probably underrepresents the proportion of the world’s

languages which are tonal since the sample is not proportional to the density of

languages in different areas.”

3 The tonal melodies have phonological and morphological status of their own in

Chatino languages (Woodbury 2019), and for diachronic study and comparison,

the melodies provide more traction than the tonal primitives on their own (see

Section 4.3).

4 For Chinese, the presence of tone, and its reconstruction, is only established for

Middle Chinese (~200–900 CE) (Mei 1970; Chen 2000: 5), and Early Middle

Chinese may have still had only an“incipient or quasi-

tonal system”(Pulleyblank

1978: 175).

5 This root was originally a verb, and different layers of now opaque derivation

across the varieties may be responsible for the lack of regular correspondence.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/18429038-250530051145-b9806271/75/Historical-Linguistics-And-Endangered-Languages-Exploring-Diversity-In-Language-Change-1st-Edition-46-2048.jpg)

![36 EricW. Campbell

3

6

de Lacy,Paul.2002.The interaction of tone and stress in OptimalityTheory.Phonology

19: 1–

32. DOI: 10.1017/

S0952675702004220.

Demuth,Katherine.1995.The acquisition of tonal systems.In Phonological Acquisition

and Phonological Theory, ed. by J.Archibald, pp. 111–

134. Hillsdale, NJ.: Lawrence

Erlbaum Associates. DOI: 10.4324/

9781315806686.

Dimmendaal, Gerrit J. 2011. Historical Linguistics and the Comparative Study of African

Languages.Amsterdam: John Benjamins. DOI: 10.1075/

z.161.

Dockum, Rikker. 2019.The tonal comparative method:Tai tone in historical per-

spective. PhD dissertation,Yale University.

Donohue, Mark. 1997.Tone systems in New Guinea. LinguisticTypology 1: 347–

386.

DOI: 10.1515/lity.1997.1.3.347

Downing, Laura J. and Annie Rialland. 2017. Introduction. In Intonation in African

Tone Languages, ed. by Laura J. Downing and Annie Rialland, pp. 1 –

16. Berlin:

De Gruyter Mouton.

Dürr,Michael.1987.A preliminary reconstruction of the proto-

Mixtec tonal system.

Indiana 11: 19–

61. DOI: 10.18441/

ind.v11i0.19-

61.

Edmondson, Jerold A. and Kenneth J. Gregerson. 1992. On five-

level tone systems.

In Language in Context: Essays for Robert E. Longacre, ed. by Shin Ja J. Hwang and

William R. Merrifield, pp. 555–576. Dallas: Summer Institute of Linguistics.

Epps, Patience and Katherine Bolaños. 2017. Reconsidering the “Makú” language

family of Northwest Amazonia. International Journal of American Linguistics 83(3):

467–507. DOI: 10.1086/691586.

Fernández de Miranda, MaríaTeresa. 1995. El protozapoteco. México, D.F.: El Colegio

de México and Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia.

Fromkin,Victoria A. 1972.Tone features and tone rules. Studies in African Linguistics

3(1): 47–76.

Gedney,William J. 1989[1972].A checklist for determining tones in Tai dialects. In

Selected Papers on ComparativeTai Studies,ed.by Robert J.Bickner,John Hartmann,

Thomas John Hudak and Patcharin Peyasantiwong, pp. 191–206. Ann Arbor:

Center for South and Southeast Asian studies, the University of Michigan.

Goldsmith,John A.1976.Autosegmental phonology.PhD dissertation,Massachusetts

Institute of Technology.

Gordon, Matthew. 2001.A typology of contour tone restrictions. Studies in Language

25(3): 423–

462. DOI: 10.1075/

sl.25.3.03gor.

Greenberg, Joseph. 1948. The tonal system of Proto-

Bantu. Word 4(3): 196–

208.

DOI: 10.1080/00437956.1948.11659343.

Guthrie, Malcolm. 1967–1971. Comparative Bantu (4 vols.). London: Gregg.

Haudricourt, André-

Georges. 1954. De l’origine des tons du vietnamien. Journal

asiatique 242: 69–

82.

Hernández Mendoza, Fidel. 2017. Tono y fonología segmental en el Triqui de

Chicahuaxtla. PhD dissertation, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Hock, Hans Heinrich. 1991. Principles of Historical Linguistics (2nd ed.). Berlin:

Mouton de Gruyter. DOI: 10.1515/

9783110219135.

Hombert, Jean-

Marie. 1974. Universals of downdrift: their phonetic basis and

significance for a theory of tone. Studies in African Linguistics, Supplement 5:

169–184.

Hombert, Jean-

Marie, John J. Ohala, and William G. Ewan. 1979. Phonetic

explanations for the development of tones. Language 55(1): 37–

58.

Hua, Zhu and Barbara Dodd. 2000. The phonological acquisition of Putonghua

(Modern Standard Chinese). Journal of Child Language 27: 3–

42. DOI: 10.1017/

S030500099900402X.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/18429038-250530051145-b9806271/75/Historical-Linguistics-And-Endangered-Languages-Exploring-Diversity-In-Language-Change-1st-Edition-49-2048.jpg)

![40 EricW. Campbell

4

0

Suárez, Jorge.A. 1973. On proto-

Zapotec phonology. International Journal of American

Linguistics 39(4): 236–

249. DOI: 10.1086/

465272.

Sullivant,John Ryan.2015.The phonology and inflectional morphology of Cháʔknyá,

Tataltepec deValdés Chatino, a Zapotecan language. PhD dissertation, University

of Texas at Austin.

Sullivant, J. Ryan. 2016. Reintroducing Teojomulco Chatino. International Journal of

American Linguistics 82(4): 393–

423. DOI: 10.1086/

688318.

Swadesh, Morris. 1947. The phonemic structure of proto-

Zapotec. International

Journal of American Linguistics 13(4): 220–

230. DOI: 10.1086/

463959.

Thurgood, Graham. 2002.Vietnamese tonogenesis: revising the model and the ana-

lysis. Diachronica 19(2): 333–

363. DOI: 10.1075/

dia.19.2.04thu.

To, Carol K. S., Pamela S. P. Cheung, and Sharynne McLeod. 2013. A population

study of children’s acquisition of Hong Kong Cantonese consonants, vowels,

and tones. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 56: 103–

122. DOI:

10.1044/1092-4388(2012/11-0080).

Upson, B.W. and Robert E. Longacre. 1965. Proto-

Chatino phonology. International

Journal of American Linguistics 31(4): 312–

322. DOI: 10.1086/

464861.

Villard, Stéphanie. 2015. The phonology and morphology of Zacatepec Eastern

Chatino. PhD dissertation, University of Texas at Austin.

Wang, William S-

Y. 1967 Phonological features of tones. International Journal of

American Linguistics 33(2): 93–

105. DOI: 10.1086/

464946.

Welmers,Wm. E. 1959.Tonemics, morphotonemics, and tonal morphemes. General

Linguistics 5(1): 1–

9.

Wichmann,Søren and EricW.Holman.2009.Temporal Stability for LinguisticTypological

Features. München: Lincom Europa.

Wiener, Seth and Rory Turnbull. 2016. Constraints of tones, vowels and consonants

on lexical selection in Mandarin Chinese.Language and Speech 59(1):59–

82.DOI:

10.1177/0023830915578000.

Woodbury,Anthony C. 2012.The astonishing typological diversity of Chatino tone

systems: a work in progress. Keynote address at the 11th Workshop on American

Indian Languages, University of California, Santa Barbara.

Woodbury,Anthony C. 2019.Verb inflection in the Chatino languages:The separate

life cycles of prefixal vs. tonal conjugational classes. Amerindia 41: 75–120.

Yang, Cathryn, James N. Stanford, and Zhengyu Yang. 2015. A sociotonetic study

of Lalo tone change in progress. Asia-Pacific Language Variation 1(1): 52–77. DOI:

10.1075/aplv.1.1.03yan.

Yang, Cathryn andYi Xu. 2019. Crosslinguistic trends in tone change:A review of

tone change studies in East and Southeast Asia. Diachronica 36(3): 417–459. DOI:

10.1075/dia.18002.yan

Yeung, H. Henry, Ke Heng Chen, and Janet F.Werker. 2013.When does native lan-

guage input affect phonetic perception? The precocious case of lexical tone.

Journal of Memory and Language 68: 123–

139. DOI: 10.1016/

j.jml.2012.09.004.

Yip, Moira. 1980.The tonal phonology of Chinese. PhD dissertation, Massachusetts

Institute of Technology.

Yip, Moira. 2002. Tone. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. DOI: 10.1017/

CBO9781139164559.

Zhu, Xiaonong 朱晓农, Lin Qing 林晴 Pachaya 趴差桠. 2015. 泰语声调的类型

和顺时针 链移 [Thai tone typology and the clockwise tonal chain shift]. 民族

语文 [Minority Languages of China] (4): 3–

18.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/18429038-250530051145-b9806271/75/Historical-Linguistics-And-Endangered-Languages-Exploring-Diversity-In-Language-Change-1st-Edition-53-2048.jpg)

![Some praised, others wept, and a sweet peace and calmness filled

my soul. As I ascended from the water, I sung the following lines

with the Spirit, and I think with the understanding also:

'But who is this that cometh forth,

Sweet as the blooming morning,

Fair as the moon, clear as the sun?

'Tis Jesus Christ adorning.'[10]

We returned singing; and truly, like the Ethiopian worshipper, we

'went on our way rejoicing.' From this time, I felt that I was newly

established in God's grace. I had more strength to withstand

temptation, more confidence to speak in the holy cause of the

Redeemer. Here, with the Psalmist, I could say, 'How love I thy law;

it is my meditation all the day.'

'Let wonder still with love unite,

And gratitude and joy;

Be holiness my heart's delight,

Thy praises my employ.'

Thus reads the narrative of such outward and inward facts as belong

to the early religious history of Joseph Badger. Its component parts

are, deep feeling, much thought, temporary doubting and

despondency, penitence, inward aspiration, prayerful reliance on

God, and at last a wide Christian fellowship, untinged by sectarian

preference, and a conscious peace and joy in God. Through the

many changes of theory, each winning admirers and having its day;

through the stormy excitements of the religious feeling in the world,

Mr. B. always retained his equilibrium and his constancy. And why?

Because he laid his basis not in dogma, not in speculation, but in

experience. By this he held his course, it being an anchor in the sea-

voyage of life, a pole-star to the otherwise doubtful wanderings of

the world's night. What can we or any one know of Divinity, except

what we hold in our inward consciousness and experience? Nothing

else. Words do not reveal holy mysteries. The soul must have God in](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/18429038-250530051145-b9806271/75/Historical-Linguistics-And-Endangered-Languages-Exploring-Diversity-In-Language-Change-1st-Edition-56-2048.jpg)

![men to make them ministers and witnesses of those things they

have seen, and of those which he shall reveal unto them. John said,

'We speak the things we do know, and testify the things we have

seen.' The Gospel is not something learned by human teaching, as

are the mathematics and divers natural sciences. St. Paul was nearer

its fountain-head and true attainment when he said, 'I neither

received it from man, neither was I taught it but by the revelation of

Jesus Christ.' 'Wo is unto me if I preach not the Gospel.' Neither

reputation nor worldly recompense prompted the apostolical

preaching. 'We preach not ourselves, but the Lord Jesus Christ.'

'Freely thou hast received, freely give.' The Gospel is not an earthly

product, but a divine institution for divine ends. The preaching of it,

therefore, is the highest possible work, demanding the greatest

deliberation and integrity. Its effects are either 'a savor of life unto

life, or of death unto death.' How delightful also is this employment,

as it brings life, light and comfort to all who yield to its elevating,

enlightening and purifying power.

These passages, written in the early years of his ministerial life, at

once recalled the second sermon[11] that the writer of this ever

heard him preach, founded on the heroic text of St. Paul, I am not

ashamed of the Gospel of Christ,[12] in which he announced the

Gospel as a divine science, as a refining power, as according with

human nature and its wants; and, indeed, as the only perfect

science of human happiness known on earth. Such is the

supremacy he unwaveringly gave to Christ, to his Gospel, and to its

genuine ministry.

The feeling that drew the mind of Mr. Badger into the ministry, was

an early one, having birth almost contemporaneously with the deep

strivings of his mind already narrated in the previous chapter. It was

the highest aspiration of his youth. Often, when at work, as early as

the autumn of 1811, then nineteen years of age, his mind scarcely](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/18429038-250530051145-b9806271/75/Historical-Linguistics-And-Endangered-Languages-Exploring-Diversity-In-Language-Change-1st-Edition-59-2048.jpg)

![CHAPTER VI.

PUBLIC LABORS IN THE PROVINCE.

From this time, I continued to improve my gift in public speaking, in

this and other neighborhoods of the town. Feeling much friendship

and care for the brethren in Ascott, I spent as much time as my

business would allow among them, which was to my instruction and

comfort, as there were in that place many faithful and experienced

Christians. As I had some leisure, and found it duty to visit the

neighboring towns, I thought it would be proper to have something

to show, upon my introduction to strange communities, what my

character and standing were at home. As I felt commissioned from

God's throne, I saw no necessity of applying to men for license or

liberty to preach, and therefore only sought a confirmation of my

moral character. It would indeed be an absurd mission that did not

include the liberty of fulfilling the duty imposed. Thus 'I did not go

up to Jerusalem to those who were Apostles before me,' though I

conferred much with 'flesh and blood.' I submitted this question to

Mr. John Gilson, who as a minister was highly respected. He

concurred with me in opinion, gave me a letter stating that my moral

and Christian character was good, and that the religious community

believed me to be called to preach the Gospel. This was singular, as

I was not a Methodist, and was in no way pledged to their peculiar

doctrines. We always had, however, a good understanding, and it

was with tears that I parted from them. Since then I have often met

them with joy, and they are still dear in my memory.[13] For one year

from the time I began to preach, this was all the letter I had, whilst

with solemn joy I went through the region of Lower Canada to

preach, experiencing the mingled cup of joy and trial common to a

missionary life, which was my heart's choice.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/18429038-250530051145-b9806271/75/Historical-Linguistics-And-Endangered-Languages-Exploring-Diversity-In-Language-Change-1st-Edition-70-2048.jpg)