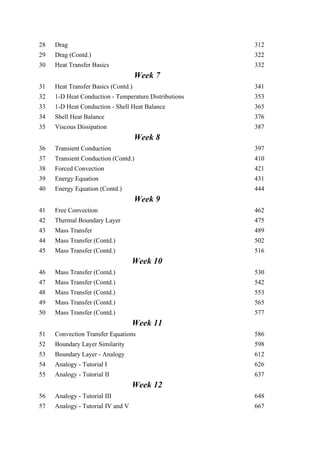

The document provides an index for a course on transport phenomena, outlining topics over 12 weeks that cover concepts like Newton's law of viscosity, shell momentum balance, boundary layers, and mass transfer. Key aspects of transport phenomena are discussed, including the governing equations for momentum, heat, and mass transfer as well as the boundary layer concept. Dimensionless groups and their importance in understanding similarity between different transport processes are also highlighted.

![inside the control volume would simply be ( )

x

x y z v

t

ρ

∂

∆ ∆ ∆

∂

kg/m2

s. So if I take the convective

momentum, conductive momentum, the x component of the pressure force, the x component of

the body force and the rate of accumulation of the x momentum, then according to the equation,

which we have written,

Rate of momentum Rate of momentum Rate of momentum Forces acting on

= -

accumulation coming in going out the system

+ ∑

all these terms together can be written and I am not going to write the full form of the

expression.

(Refer Slide Time: 21:00)

What I am going to do is I am going to simply give you the compact form of this equation after

some simplification which is [ ]

.

Dv

p g

Dt

ρ τ ρ

= −∇ − ∇ + . This equation in tensor notation is

known as the equation of motion, where the

Dv

Dt

ρ is essentially

mass per unit volume(

ρ)×acceleration

Dv

Dt

. p

∇ is pressure, Newton, force per unit volume.

Then you have .τ

∇ which is ( )

x

τ

∂

∂

, shear force per unit volume and g

ρ is gravitational force

116](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/npteltpnotesfull-220501122717/85/NPTEL-TP-Notes-full-pdf-120-320.jpg)

![Transport Phenomena

Prof. Sunando DasGupta

Department of Chemical Engineering

Indian Institute of Technology, Kharagpur

Lecture 11

Equations of Change for Isothermal Systems (Cont.)

This is going to be a tutorial class on the concept that we have covered in, for equations of

motion, mostly Navier–Stokes equation. What we have seen in the previous two classes is the

fundamental concepts of derivatives, they are different types. The equations of continuity and

the equation of motion, we have a comprehensive system right now which could address any

of the fluid mechanics problems at least up to the point of governing equation. The concepts

behind choosing the boundary condition will remain unchanged from whatever we have

discussed previously. So just a quick recapitulation of what we have done over here is, we

have seen the equation of motion [ ]

.

Dv

p g

Dt

ρ τ ρ

= −∇ − ∇ + . When in the equation of motion

you add the constant ρ and constant μ and equation of continuity what you get is Navier–

Stokes equation 2

Dv

p v g

Dt

ρ µ ρ

= −∇ + ∇ + .

So

Dv

Dt

ρ is mass per unit volume multiplied by acceleration, so this becomes force per unit

volume. Similarly, p

∇ is also force due to pressure per unit volume. 2

v

µ∇ is viscous force

per unit volume and ρg is the gravitational force or the body force per unit volume. So all

terms in Navier–Stokes equation are nothing but force per unit volume. And the special case

would emerge if you assume that it is an inviscid fluid or the viscosity of fluid is

insignificant. What you get from Navier–Stokes equation is something which is known as

Euler's equation for inviscid flow of liquids

Dv

p g

Dt

ρ ρ

= −∇ + where this μ term would

simply be dropped. Now the expressions for different components, x, y, z components of

Navier–Stokes equation in Cartesian, cylindrical and spherical coordinates are given in any

textbook. You can refer either to Bird, Stewart and Lightfoot or or Fox McDonald, or any of

the textbooks will contain the expression for Navier–Stokes equation in different coordinate

systems.

So what you need to do in that is first see what kind of geometry you have in hand. Then

accordingly choose whether it is Cartesian, spherical or cylindrical coordinate has to be

120](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/npteltpnotesfull-220501122717/85/NPTEL-TP-Notes-full-pdf-124-320.jpg)

![For 5

η = , y δ

= and the expression for δ will be

5.0

U

x

δ

ν

= . So if I replace

U

x

ν

in the

expression of δ*

, then it is simply going to be *

0

1

5

df

d

d

η

δ

δ η

η

= − ⋅

∫

(Refer Slide Time 24:00)

I will perform the integration now. So after integration, [ ]

*

0

1

5

f

η

δ

η

δ

= −

Now this is the complete expression that I am going to use to obtain the solution to the

problem where the value of

*

δ

δ

to be evaluated for 5

η = and as η → ∞ . The corresponding

values f is to be provided from the table.

(Refer Slide Time 25:59)

For 5

η = , the expression would become, [ ]

*

1

5 3.28324 0.34334

5

δ

δ

=− =

227](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/npteltpnotesfull-220501122717/85/NPTEL-TP-Notes-full-pdf-231-320.jpg)

![*

δ

δ

at η=8 which is same as η → ∞ would be [ ]

*

1

8 6.27923 0.34415

5

δ

δ

=− = . So you can

compare these two values and can see that

* *

5

η η

δ δ

δ δ

= →∞

≈

(Refer Slide Time 30:05)

So just the use of the table would give you some idea of how does displacement thickness

varies for different values of η, for different values of y and so on.

The next question that I posed to you to calculate the value of y

v

U

at the edge of the boundary

layer. I will write the expression for vy which we have derived before which is

1

2

y

U f

v f

x

ν

η

η

∂

= −

∂

. So y

v

U

would simply be

1

2

y

v f

f

U Ux

ν

η

η

∂

= −

∂

. This can be

expressed in terms of [ ]

1

2 Re

y

x

v

f f

U

η ′

= − .

(Refer Slide Time 31:48)

229](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/npteltpnotesfull-220501122717/85/NPTEL-TP-Notes-full-pdf-233-320.jpg)

![So, at the edge of the boundary layer, that means at η=5,

[ ]

1

5 0.99155 3.28329

2 Re

y

x

v

U

= × − , this you get from the table. Therefore,

0.84

Re

y

x

v

U

= .

(Refer Slide Time 33:07)

This gives me another insight into this boundary layer. On the solid surface you have vx and

vy both zero. You have vx inside the boundary layer and outside this vx is going to be equal to

U but what happens to vy in here? In other words can you call the edge of the boundary layer

as a streamline? Now in order for it to be streamline, it has to satisfy the basic properties of

the streamline which is that the particle which is on a streamline will remain on that

streamline and no particle, no fluid can cross a streamline. The moment you have flow across

a line, then that line cannot be a streamline. So you have yourself found out in the previous

problem that at the edge of the boundary layer, vy is not zero. vy is a function of Reynolds

230](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/npteltpnotesfull-220501122717/85/NPTEL-TP-Notes-full-pdf-234-320.jpg)

![end would give rise to significant pressure drag. In fact most of the drag that is experienced

by the moving spherical object in air is due to pressure drag.

It's the frictional drag constitutes only about 5 to 10%. But the situation gets reversed when

you go into turbulent boundary layer. The turbulent boundary layer, since the fluid molecules

carry more momentum with it, the point of separation on the sphere would start to move

backwards resulting in smaller wakes and smaller adverse pressure gradient. This is the

reason that turbulent boundary layer is often preferred over a blunt body. So for a blunt

object, we would rather have turbulent flow rather than laminar flow on a boundary layer.

So the below figure of CD vs Re is a very well-known figure and of course for different

objects, the values of this CD would be different and its variation with Re would also be

different. But this roughly gives you an idea, starting at the Stokes regime, the laminar flow

and the turbulent flow, how CD changes, how wakes are formed, how wakes are reduced and

so on.

(Refer Slide Time: 26:16)

So if the red circle is a car, then the next car [the red rectangle] would like to be in the wake

formed by the first car and so on, such that it would have a pressure drag. So sometimes

intelligent use of the wake formed by the previous object would allow the object next to it in

a more intelligent fashion with less effort. So that is what we are going to explore further with

our example from cricket.

319](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/npteltpnotesfull-220501122717/85/NPTEL-TP-Notes-full-pdf-323-320.jpg)

![Transport Phenomena

Prof. Sunando DasGupta

Department of Chemical Engineering

Indian Institute of Technology, Kharagpur

Lecture Number 30

Heat Transfer Basics

So far we have studied fluid mechanics, that is momentum transfer and details about the

boundary layers. What we saw is that the flow of momentum because of a difference in

velocity in between adjacent layers of fluid can be expressed in terms of Newton's law. So it's

the shear stress which also signifies the molecular transport of momentum, that was the basis

of our analysis of fluid motion. And there we have chosen initially a control volume and saw

what are the different methods, ways by which momentum is entering into the control

volume. So the rate of momentum coming into the control volume through convection as well

as molecular means which is conductive momentum transfer. So at steady state

rate of in - rate of out + sum of all forces = 0 and when I say all forces they can be body

force, for example gravity, or surface force acting on the control volume. If it is not at steady

state that means if all these contributions are not balanced then the control volume is going to

have an acceleration or deceleration of its own. So that was that was the starting point for the

derivation of Navier Stokes equation of motion of which Navier Stokes equation is a special

case where the viscosity and other properties are constant. So when we got to Navier Stokes

equation, [ ]

.

Dv

p g

Dt

ρ τ ρ

= −∇ − ∇ + , we saw that the left hand side of Navier Stokes equation

was

Dv

Dt

ρ which contains not only the transient effects, that means

v

t

∂

∂

, at the same time it

also has all the convective transport of momentum terms associated with it.

When we move to the right hand side of Navier–Stokes equation, we got a gradient in

pressure, p

−∇ , which is one of the surface forces, another term was due to viscous forces,

[ ]

.τ

− ∇ , and the third term that we got in Navier–Stokes equation was the effect of body

forces denoted by g

ρ where g is the acceleration due to gravity. So that was the equation of

motion which we have derived out of the simple consideration of Newton's second law for an

open system in which mass is allowed to come in with some velocity and go out as well. We

have seen examples of the use of Navier Stokes equation in different coordinate systems and

we saw how the use of Navier Stokes equation has simplified the overall treatment of fluid

mechanics leading to the accurate evaluation of the velocity in a flowing fluid.

332](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/npteltpnotesfull-220501122717/85/NPTEL-TP-Notes-full-pdf-336-320.jpg)

![(Refer Slide Time: 30:48)

And the third condition could be that I have a convection surface condition where you have

surface which is solid, on this side you have a liquid let’s say and the profile of temperature is

this where you have T , the temperature over here is T and the heat transfer coefficient

involved is h. So heat will come from here by means of conduction and from here to out by

means of convection.

So what happens at steady-state is then

0

0

x

dT

k

dx =

− = , this essentially denotes the amount of

heat which comes in by conduction from the interior up to this point has to be equal to the heat

which goes out of the convection and if I use Newton’s law which would simply be

[ (0, ) ]

h T t T

− .

So, the convective heat loss must be equal to the convective heat which is coming to the

interface. So by conduction you have some amount of heat coming in and by convection the

same amount of heat is going out. So, this (0, )

T t denotes the temperature of the interface at

any given time at location x = 0 and T is the constant temperature of the bulk fluid situated far

from the solid wall. So, this is the convection surface condition.

So, we would use the conduction equation to start with the appropriate coordinate systems with

appropriate boundary conditions. And quickly try to solve and see if we can get the temperature

profile of a solid object which is experiencing conduction. Initially we would restrict ourselves

to the case of steady-state where the temperature could be a function of x, y, z or , ,

r z

or

351](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/npteltpnotesfull-220501122717/85/NPTEL-TP-Notes-full-pdf-355-320.jpg)

![expression. So, if you integrate this expression, what you would get is simply,

0

ln

exp[( ) ]

exp[( ) ]

i

t

s

s i

s

i

s

i i

VC d

dt

hA

VC

t

hA

hA

t

VC

hA

T T

t

T T VC

= −

= −

= −

−

= = −

−

And looking at, therefore the temperature of the object would change in exponential fashion

with time and the time constant of the process is simply the inverse of what I have written

inside the bracket.

So, this is the convective heat transfer coefficient, this is the surface area, As, VC

. So, the

time constant of the process can be written as

1

s

VC

hA

. And as I mentioned before,

1

s

hA

is

the resistance due to conduction and VC

is some sort of thermal capacitance of the system.

So, the thermal constant of a process of quenching or of the process of changing the

temperature of a solid when it is exposed to a convection environment would be, this thermal

constant would depend upon the resistance to convection and the thermal capacity of the

system.

So, the behaviour of the variation of temperature with time is analogous to the voltage decay

that occurs when a capacitor is discharged through a resistor in an electrical circuit. So of

course, the higher the value of , the system will respond slowly in terms of the change in

temperature with time. But this gives you a very simple way to treat the transient conduction

in solid, provided you can use the lumped capacitance model.

So next we will quickly see how this constant, the that I have referred to in terms of s

hA

VC

how it can be combined to give you some more insight into the process. So, I am going to

start with the expression for which is s

hA

VC

. And therefore this can be written, this and I

405](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/npteltpnotesfull-220501122717/85/NPTEL-TP-Notes-full-pdf-409-320.jpg)

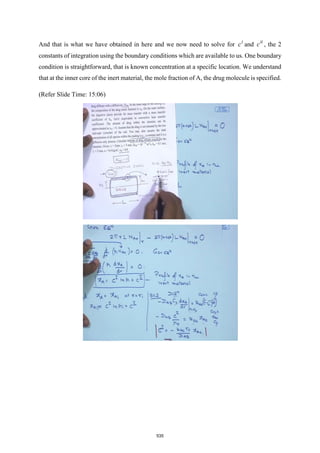

![I will write it once again that 0

6

(5 10 ) ln i

Ai

A

A x

r

x x

r

−

= + . Okay. So we realise that at 0

r r

=

that means at the outer edge of the inert coating, my 0

A

A

x x

= , let us call it at 0

A

x and we

understand that at Ai

x = 0.9, the value of 3

10

3

i

r −

= m and 3

0 0

5 1

r −

= m. So when you put

these values in here, what you are going to get is 0

A

x which is the mole fraction of component

A at the outside of the inert layer and is simply going to be 0

6 3

(5 10 ) ln

5

Ai A

A i

x x

x −

= +

So 0

A

x = 7

3.527 10−

. So it essentially tells the concentration of the drug on the outside is simply

going to be 7

3.527 10−

. The next that is remaining is rate of drug release which has been

asked, into the intestine that as a drug designer you must find out and we understand that since

I know 0

A

x , I should be able to multiply the convective movement of the drug away from the

outside of the inner core to the digestive juices.

So I am going to have this as 0

[ ]

ac A A t

area k x x C

− . So, ideally if you look at the total amount

of convection of the species away from the outer core of the inert material it is simply going to

be the convective mass transfer coefficient multiplied by the concentration difference. So that

when you multiply with the outer area of the inert coating it would give you in kg/s, in SI units,

what is the total amount of drugs that will diffuse through the inert layer, reach the outside of

the net layer and by a convection process initiated by the movement of the intestinal juices

inside the intestine that is going to get dissolved.

539](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/npteltpnotesfull-220501122717/85/NPTEL-TP-Notes-full-pdf-543-320.jpg)