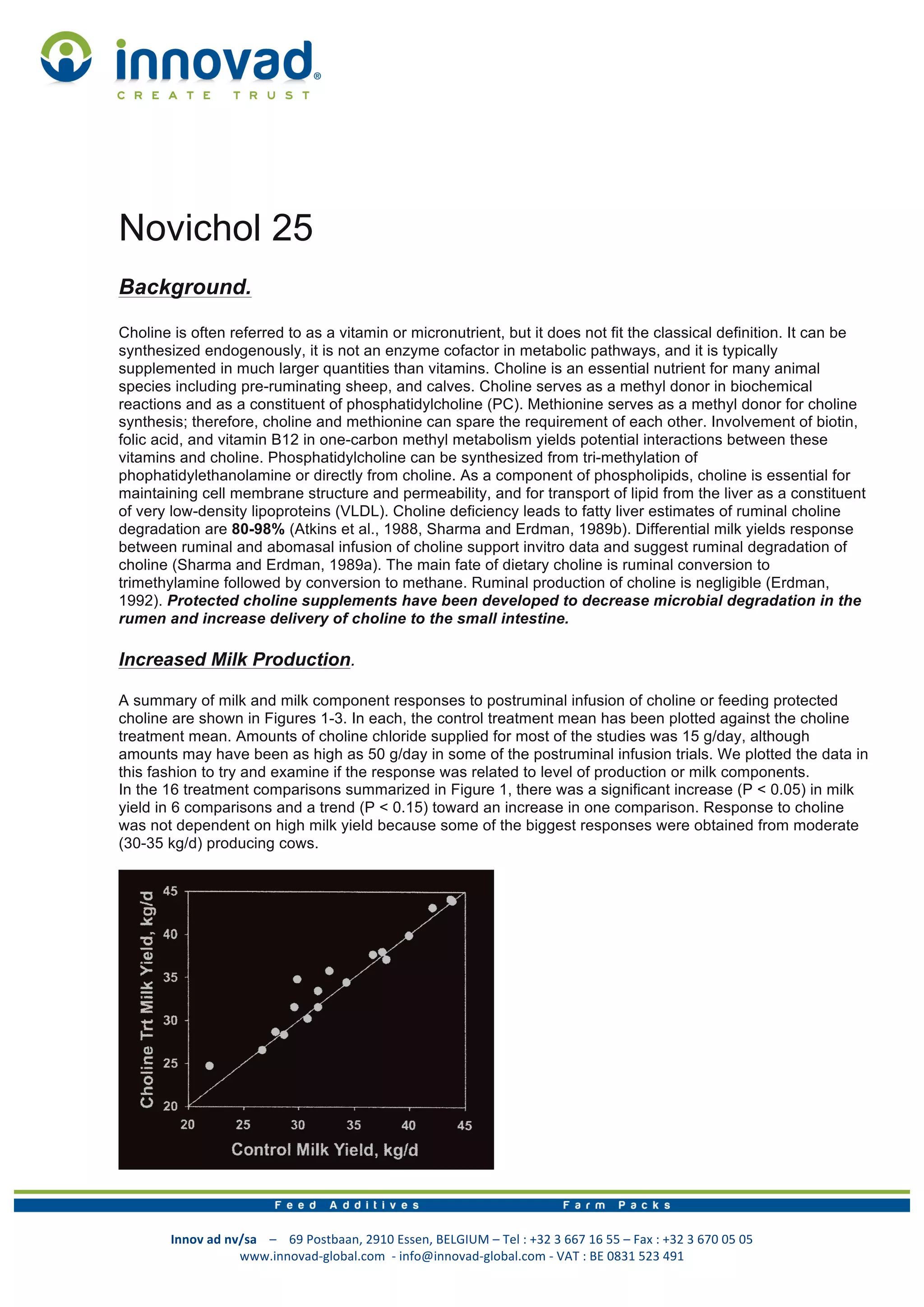

This document discusses choline and its role in dairy cattle. It begins with background information on choline, noting that it is essential for cell membrane structure and lipid transport. Though not a vitamin, it acts as a methyl donor. The document then reviews studies showing that supplemental choline, protected from rumen degradation, can increase milk yield and fat percentage in dairy cows. It also may help prevent fatty liver in cows during the transition period due to its role in lipid transport. The final section discusses niacin and its anti-lipolytic effects when given in large pharmacological doses, though these effects are transient.