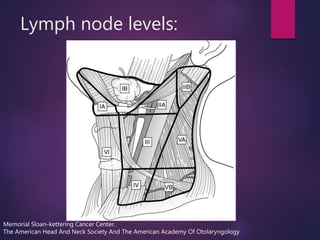

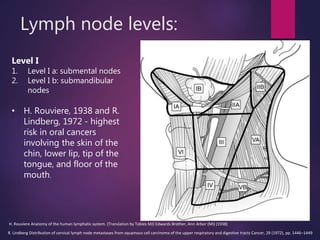

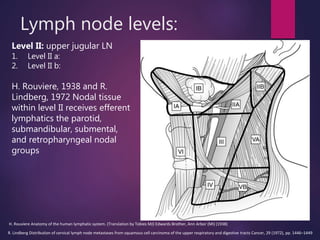

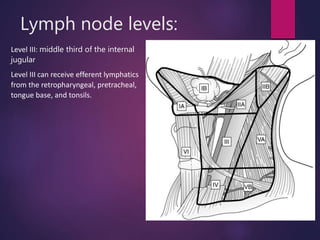

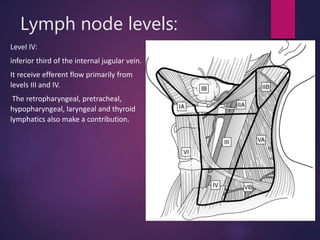

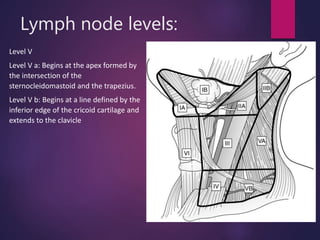

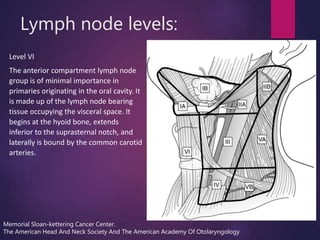

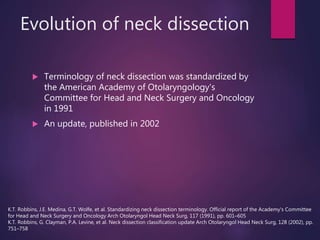

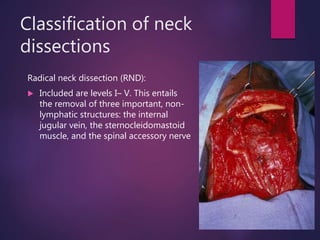

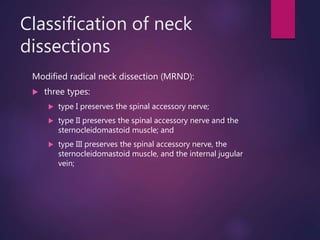

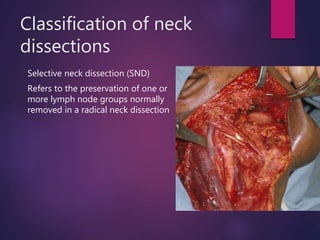

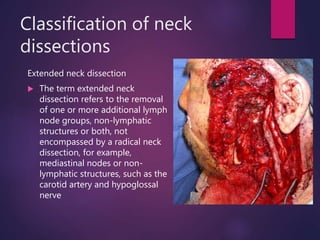

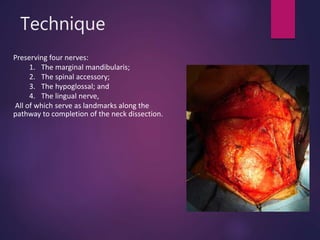

This document outlines a journal club presentation on neck dissection, covering its nomenclature, classification, and technique as presented by Dr. Kamini Dasena and guided by multiple specialists. It details the anatomical levels of lymph nodes, the evolution of neck dissection techniques, and complications associated with the procedures. The presentation emphasizes the importance of identifying and managing metastatic lymph nodes in head and neck cancer patients.

![References

[1] W.M. Mendenhall, R.R. Million, N.J. Cassisi Elective neck irradiation in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck Head Neck Surg, 3

(1980), pp. 15–19

[2] E.R. Carlson, I. Miller Surgical management of the neck in oral cancer Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am, 18 (2006), pp. 533–546

[3] H. Rouviere Anatomy of the human lymphatic system. (Translation by Tobies MJ) Edwards Brother, Ann Arbor (MI) (1938)

[4] R. Lindberg Distribution of cervical lymph node metastases from squamous cell carcinoma of the upper respiratory and digestive tracts

Cancer, 29 (1972), pp. 1446–1449

[5] P. Strauli The lymphatic system and cancer localization R.W. Wiser, Tl Ado, S. Wood (Eds.), Endogenous factors influencing host-tumor

balance, University of Chicago Press, Chicago (1967), pp. 249–254

[6] K.T. Robbins, J.L. Atkinson, R.M. Byers, et al. The use and misuse of neck dissection for head and neck cancer J Am Coll Surg, 193 (2001), pp.

91–102

[7] H.C. Pillsbury, M. Clark A rationale for therapy of the N0 neck. Joseph H. Ogura Lecture Laryngoscope, 107 (1997), pp. 1294–1315

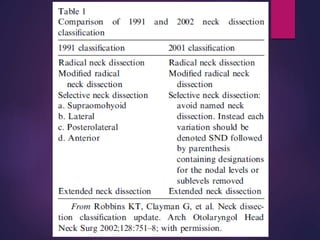

[8] K.T. Robbins, G. Clayman, P.A. Levine, et al. Neck dissection classification update Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 128 (2002), pp. 751–758

[9] J.P. Shah Foreward J. Gavilan, J. Herranz, L.W. DeSanto (Eds.), Functional and neck dissection, Thieme, New York (2002), p. vii

[10] G.W. Crile Excision of cancer of the head and neck with special reference to the plan of dissection based upon one hundred thirty-two

operations JAMA, 47 (1906), pp. 1780–1786

[11] G.W. Crile On the surgical treatment of cancer of the head and neck Transactions Southern Surgical Gynecological Association, 18 (1905), pp.

109–127

[12] G.W. Crile Carcinoma of the jaws, tongue, cheek and lips Surg Gynecol Obstet, 36 (1923), pp. 159–162

[13] H. Martin, B. Delvalle, H. Ehrlich, et al. Neck dissection Cancer, 4 (1951), pp. 441–499

[14] G.E. Ward, J.O. Robben A composite operation for radical neck dissection and removal of cancer of the mouth Cancer, 4 (1951), pp. 98–109

[15] C.V. Calearo, G. Teatini Functional neck dissection: anatomical grounds, surgical technique clinical observations Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol, 92

(1983), pp. 215–222](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/journalclub8neckdissection-200808092048/85/Neck-Dissection-Nomenclature-Classification-and-Technique-57-320.jpg)

![References

[16] E. Bocca Supraglottic laryngectomy and functional neck dissection J Laryngol Otol, 80 (1966), pp. 831–838

[17] J. Gavilan, A. Monux, J. Herranz, et al.Functional neck dissection: surgical technique Operative Techniques in Otolaryngology-Head and Neck

Surgery, 4 (1993), pp. 258–265

[18] O. Suarez El problema de las metastasis linfaticas y alejades del cancer de laringe e hipofaringe Rev Otorrinolaringol Santiago, 23 (1963), pp.

83–99

[19] K.T. Robbins, J.E. Medina, G.T. Wolfe, et al. Standardizing neck dissection terminology. Official report of the Academy's Committee for Head

and Neck Surgery and Oncology Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 117 (1991), pp. 601–605

[20] J.E. Medina A rational classification of neck dissections Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 100 (1989), pp. 169–176

[21] J.P. Shah, F.C. Candela, A.K. Poddar The patterns of cervical lymph node metastases from squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity Cancer,

66 (1990), pp. 109–113

[22] R.H. Spiro, E.W. Strong Discontinuous partial glossectomy and radical neck dissection in selected patients with epidermoid carcinoma of the

mobile tongue Am J Surg, 126 (1973), pp. 544–546

[23] C.R. Leemans, R. Tiwari, J.J. Nauta, et al. Discontinuous versus in-continuity neck dissection in carcinoma of the oral cavity Arch Otolaryngol

Head Neck Surg, 117 (1991), pp. 1003–1006

[24] J.P. Shah Head and neck surgery and oncology (3rd edition)Elsivier, New York (2003)

[25] D. Kademani, E.J. Dierks A straight-line incision for neck dissection: technical note J Oral Maxillofac Surg, 63 (2005), pp. 563–565

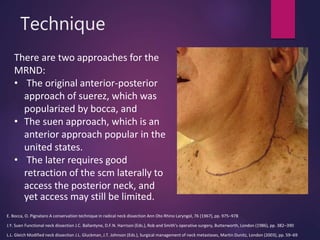

[26] E. Bocca, O. Pignataro A conservation technique in radical neck dissection Ann Oto Rhino Laryngol, 76 (1967), pp. 975–978

[27] J.Y. Suen Functional neck dissection J.C. Ballantyne, D.F.N. Harrison (Eds.), Rob and Smith's operative surgery, Butterworth, London (1986), pp.

382–390

[28] L.L. Gleich Modified neck dissection J.L. Gluckman, J.T. Johnson (Eds.), Surgical management of neck metastases, Martin Dunitz, London

(2003), pp. 59–69

[29] J. Yoel, C.A. Linares The Schobinger incision: Its advantages in radical neck dissections Am J Surg, 108 (1964), pp. 526–528

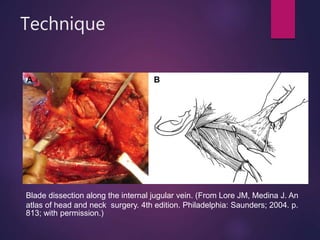

[30] J.E. Medina, J.M. Loré The neck J.M. Loré, J.E. Medina (Eds.), An atlas of head and neck surgery (4th edition. Chapter 24), Elsevier, Philadelphia

(2005), p. 804](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/journalclub8neckdissection-200808092048/85/Neck-Dissection-Nomenclature-Classification-and-Technique-58-320.jpg)

![References

[31] R.M. Byers, R.S. Weber, T. Andrews, et al. Frequency and therapeutic implications of “skip metastasis” in the neck from squamous carcinoma

of the tongue Head Neck, 19 (1997), pp. 14–19

[32] J.P. Shah, F.C. Candela, A.K. Poddar The pattern of cervical lymph node metastases from squamous carcinoma of the oral cavity Cancer, 66

(1990), pp. 109–113

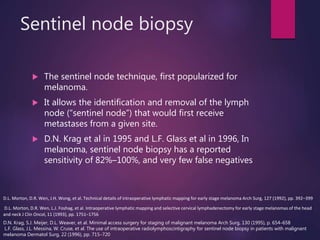

[33] D.L. Morton, D.R. Wen, J.H. Wong, et al. Technical details of intraoperative lymphatic mapping for early stage melanoma Arch Surg, 127

(1992), pp. 392–399

[34] D.L. Morton, D.R. Wen, L.J. Foshag, et al. Intraoperative lymphatic mapping and selective cervical lymphadenectomy for early stage

melanomas of the head and neck J Clin Oncol, 11 (1993), pp. 1751–1756

[35] T.D. Schellenberger Sentinal lymph node biopsy in the staging of oral cancer Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am, 18 (2006), pp. 547–563

[36] D.N. Krag, S.J. Meijer, D.L. Weaver, et al. Minimal access surgery for staging of malignant melanoma Arch Surg, 130 (1995), pp. 654–658

[37] L.F. Glass, J.L. Messina, W. Cruse, et al. The use of intraoperative radiolymphoscintigraphy for sentinel node biopsy in patients with malignant

melanoma Dermatol Surg, 22 (1996), pp. 715–720

[38] F.J. Civantos, C. Gomez, C. Duque, et al. Sentinal node biopsy in oral cavity cancer: correlation with PET scan and immunohistochemistry Head

Neck, 25 (2003), pp. 1–9

[39] K.T. Pitman, J.T. Johnson, M.L. Brown, et al. Sentinal lymph node biopsy in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma Laryngoscope, 112 (2002),

pp. 2101–2113 Am, 18 (2006), pp. 547–563

[36] D.N. Krag, S.J. Meijer, D.L. Weaver, et al. Minimal access surgery for staging of malignant melanoma Arch Surg, 130 (1995), pp. 654–658

[37] L.F. Glass, J.L. Messina, W. Cruse, et al. The use of intraoperative radiolymphoscintigraphy for sentinel node biopsy in patients with malignant

melanoma Dermatol Surg, 22 (1996), pp. 715–720

[38] F.J. Civantos, C. Gomez, C. Duque, et al. Sentinal node biopsy in oral cavity cancer: correlation with PET scan and immunohistochemistry Head

Neck, 25 (2003), pp. 1–9

[39] K.T. Pitman, J.T. Johnson, M.L. Brown, et al. Sentinal lymph node biopsy in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma Laryngoscope, 112 (2002),

pp. 2101–2113](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/journalclub8neckdissection-200808092048/85/Neck-Dissection-Nomenclature-Classification-and-Technique-59-320.jpg)

![References

[[40] N.C. Hyde, E. Prvulovich, L. Newman, et al. A new approach to pre-treatment assessment of the N0 neck in oral squamous cell carcinoma: the

role of sentinel node biopsy and positron emission tomography Oral Oncol, 39 (2003), pp. 350–360

[41] K.T. Pitman, A. Ferlito, K.O. Devaney, et al. Sentinal lymph node biopsy in head and neck cancer Oral Oncol, 39 (2003), pp. 343–349

[42] P.E. Anderson, F. Warren, J. Spiro, et al. Results of selective neck dissection in management of the node positive neck Arch Otolaryngol Head

Neck Surg, 128 (2002), pp. 1180–1184

[43] S.A. McHam, D.J. Adelstein, L.A. Rybicki, et al. Who merits a neck dissection after definitive chemoradiotherapy for N2-N3 sqaumous cell head

and neck cancer? Head Neck, 25 (2003), pp. 791–797

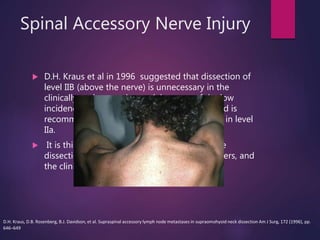

[44] D.H. Kraus, D.B. Rosenberg, B.J. Davidson, et al. Supraspinal accessory lymph node metastases in supraomohyoid neck dissection Am J Surg,

172 (1996), pp. 646–649

[45] A.A. de Jong, J.J. Manni Phrenic nerve paralysis following neck dissection Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol, 248 (1991), pp. 132–134

[46] R.W. Babin, W.R. Panje The incidence of vasovagal reflex activity during radical neck dissection

Laryngoscope, 90 (1980), pp. 1321–1323

[47] M.J. Wheatley, T.R. Meltzer The management of unsalvageable free flaps J Reconstr Microsurg, 12 (1996), pp. 227–229

[48] G.D. Becker, G.J. Parell Cefazolin prophylaxis in head and neck cancer surgery Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol, 88 (1979), pp. 183–186

[49] G. Mombelli, L. Coppens, P. Dor, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis in surgery for head and neck cancer: comparative study of short and prolonged

administration of carbencillin J Antimicrob Chemother, 7 (1981), pp. 665–671

[50] B. Cady Lymph node metastases: indicators but not governors of survival Arch Surg, 119 (1984), pp. 1067–1072

[51] A. Ferlito, A. Rinaldo, K.T. Robbins, et al. Changing concepts in the surgical management of cervical node metastasis Oral Oncol, 39 (2003), pp.

429–435

[52] L.P. Kowalski, J. Magrin, F. Waksman, et al. Supraomohyoid neck dissection in the treatment of head and neck tumors: survival results in 212

cases Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 119 (1993), pp. 958–963

[53] G.E. Ghali, B.D.L. Li, E.A. Minnard Management of the neck relative to oral malignancy Selected Readings in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 6 (2)

(1998), pp. 1–36](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/journalclub8neckdissection-200808092048/85/Neck-Dissection-Nomenclature-Classification-and-Technique-60-320.jpg)