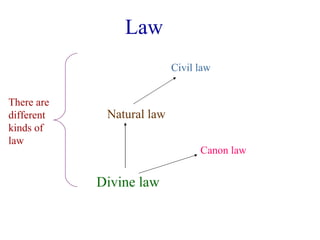

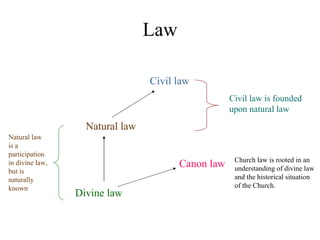

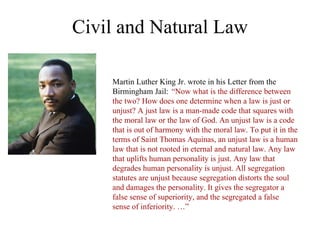

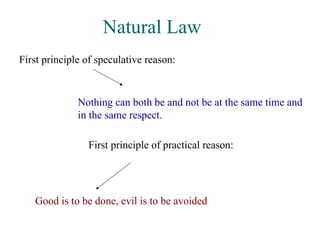

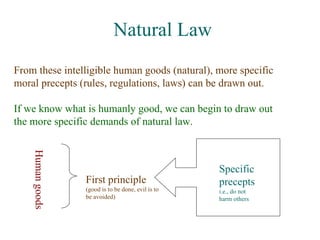

1. There are different kinds of law, including divine law, natural law, canon law, and civil law. Natural law participates in divine law and is known through reason, while civil law is man-made.

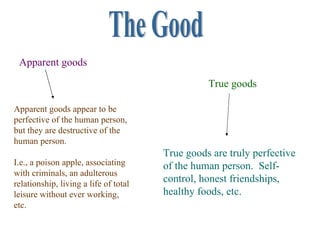

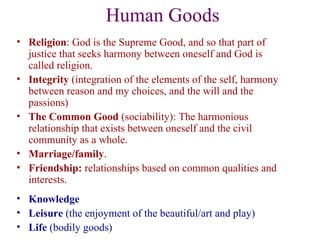

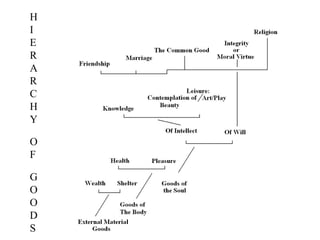

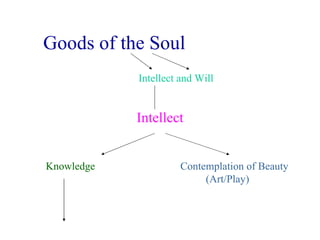

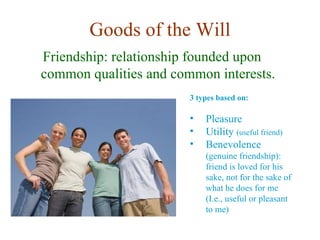

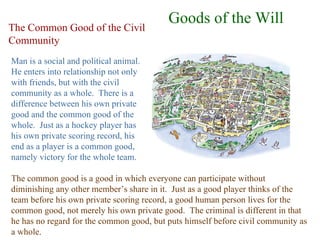

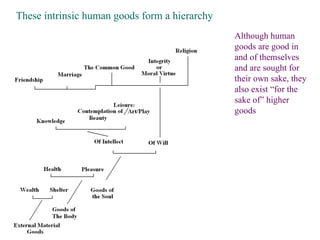

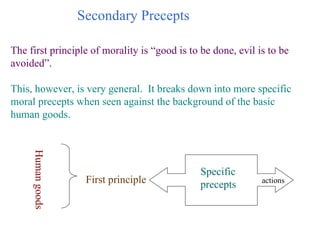

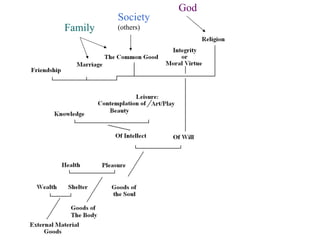

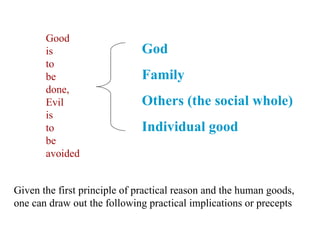

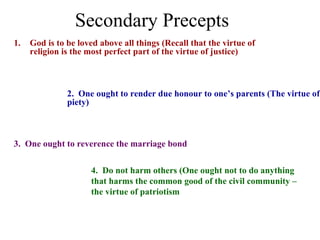

2. Basic human goods include life, knowledge, play, friendship, religion, and integrity. These goods form a hierarchy and serve as the basis for deriving more specific moral precepts from the fundamental principle of doing good and avoiding evil.

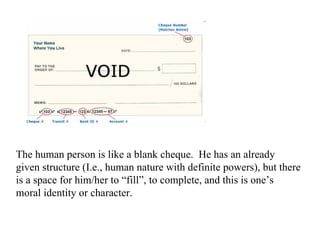

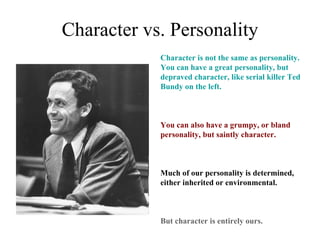

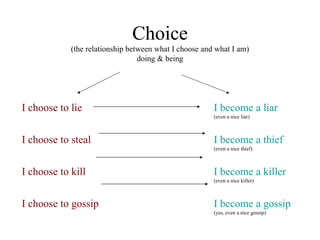

3. Through free choice, a person shapes their own moral character and identity. Repeated choices to do good or evil over time determine the kind of person one becomes.