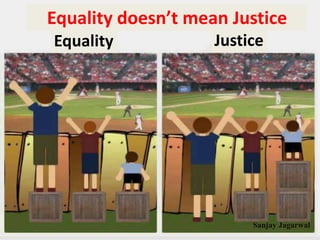

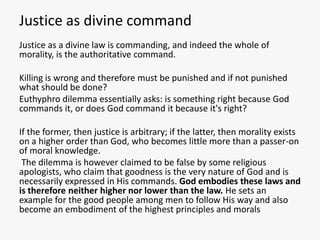

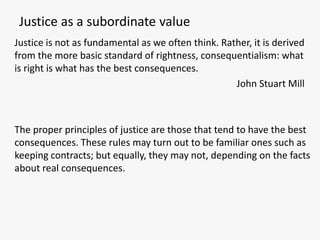

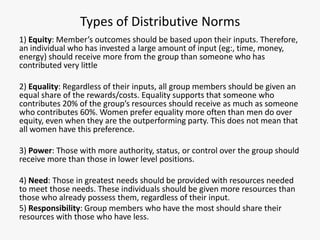

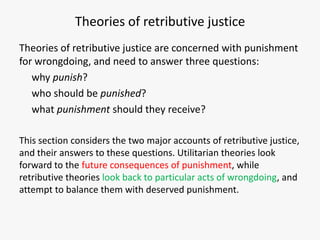

Equality and justice are related but distinct concepts. Equality refers to treating all people the same, while justice considers fairness and individual circumstances and outcomes. True justice cannot be achieved through equality alone. Different cultures understand justice in varying ways based on their shared history and beliefs. Key debates around justice include whether it stems from divine commands, natural law, human design, or a balance of consequences. Theories of justice also consider how to distribute goods fairly in a society.