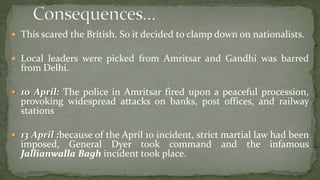

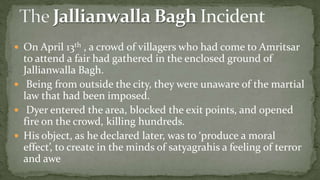

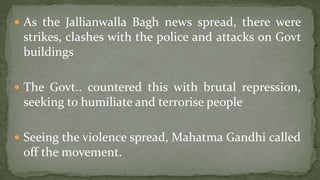

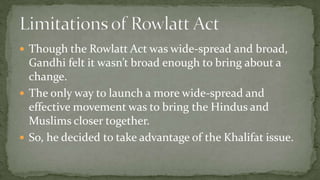

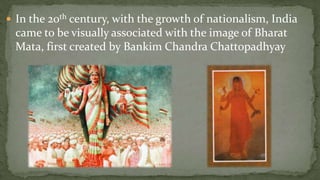

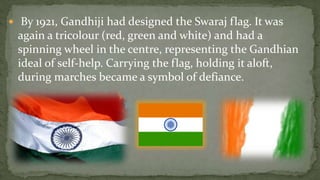

The document discusses the spread of nationalism in India following 1919 and the development of the non-cooperation and civil disobedience movements. It explains how Gandhi returned to India in 1915 and used his concept of satyagraha, or non-violent resistance, to organize peasants and mill workers. In response to the Rowlatt Acts and Jallianwala Bagh massacre, Gandhi launched a nationwide non-cooperation movement in 1920 combining demands for self-rule and support of the Ottoman Khalifa. Different social groups participated in the movement with their own interpretations of swaraj or self-rule.