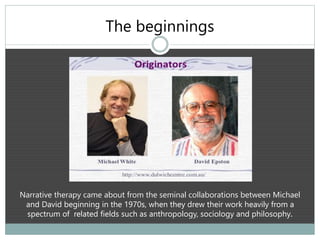

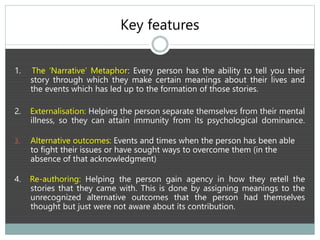

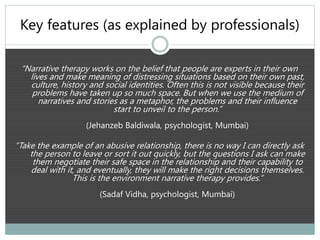

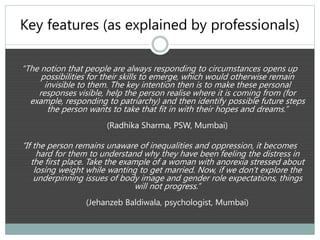

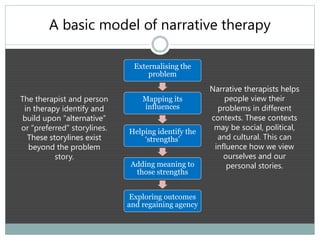

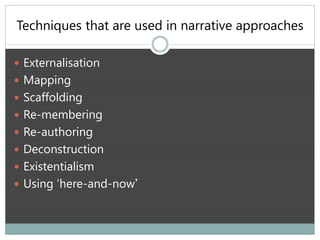

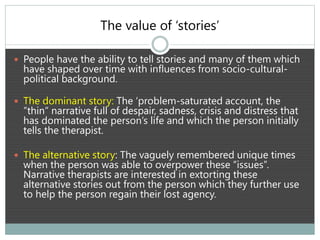

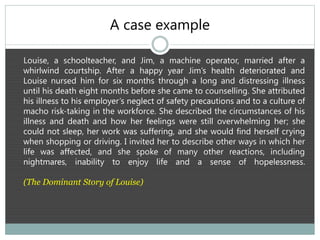

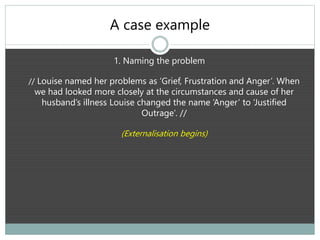

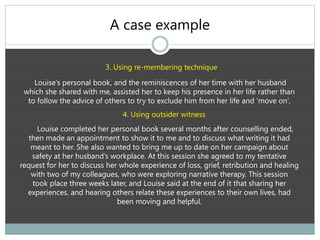

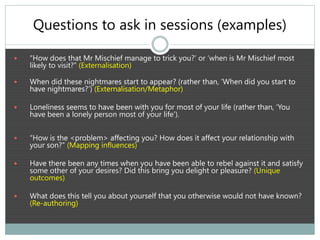

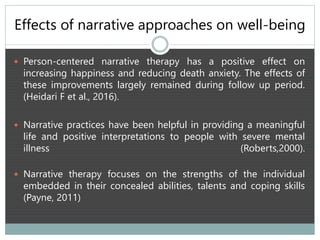

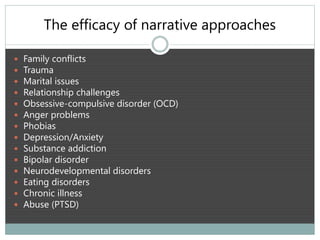

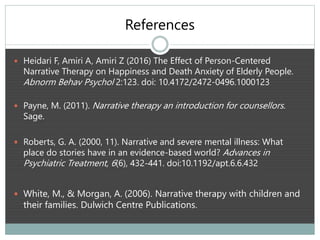

The document discusses narrative therapy as a respectful, non-blaming counseling approach that emphasizes people as the experts in their own lives and seeks to separate problems from individuals. It outlines key features of narrative therapy, including externalization, re-authoring, and mapping influences, while examining the importance of storytelling in personal agency and healing. Additionally, it provides case examples demonstrating how narrative therapy can help individuals identify alternative stories and regain agency in their lives, ultimately enhancing their well-being.