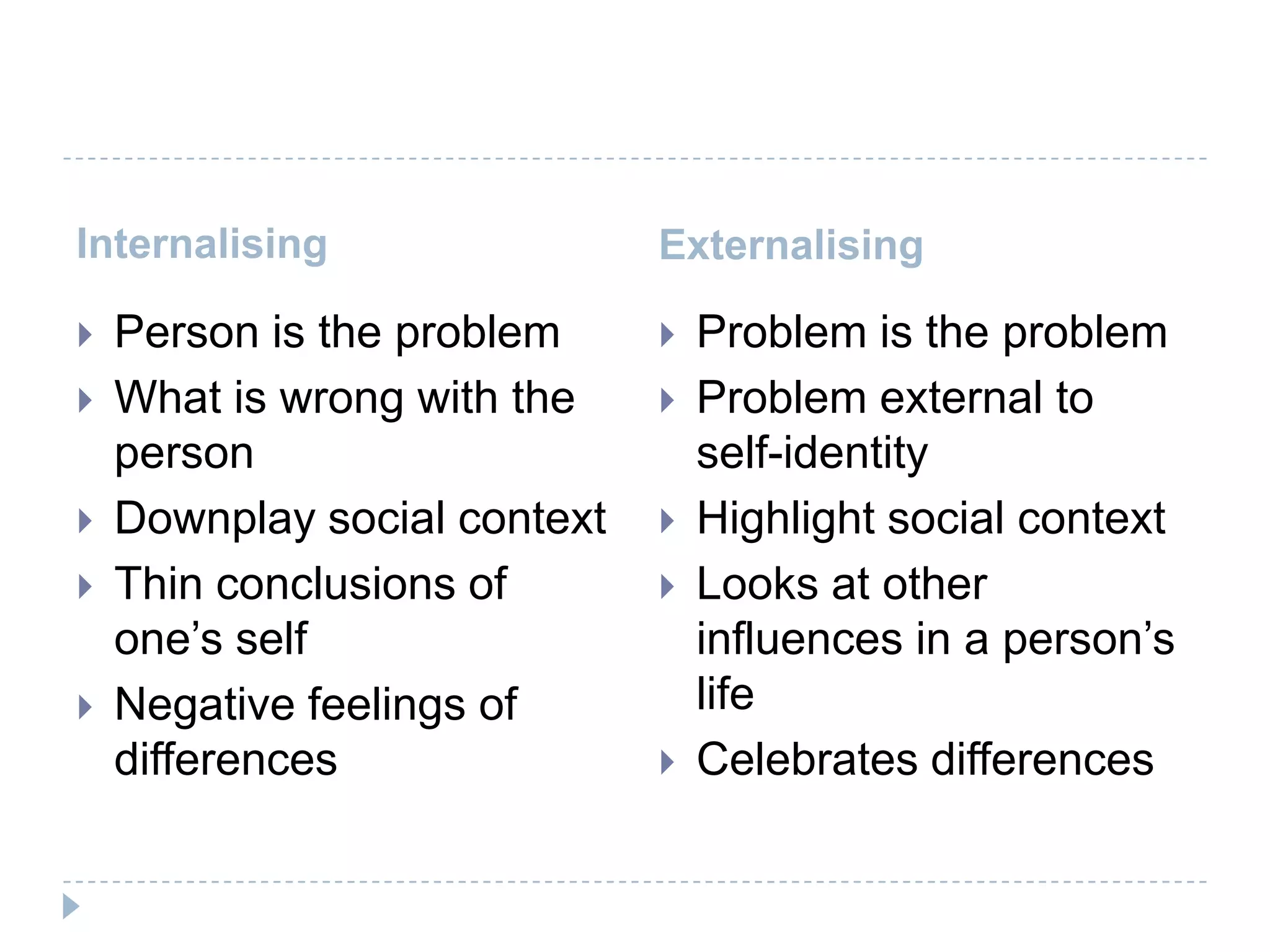

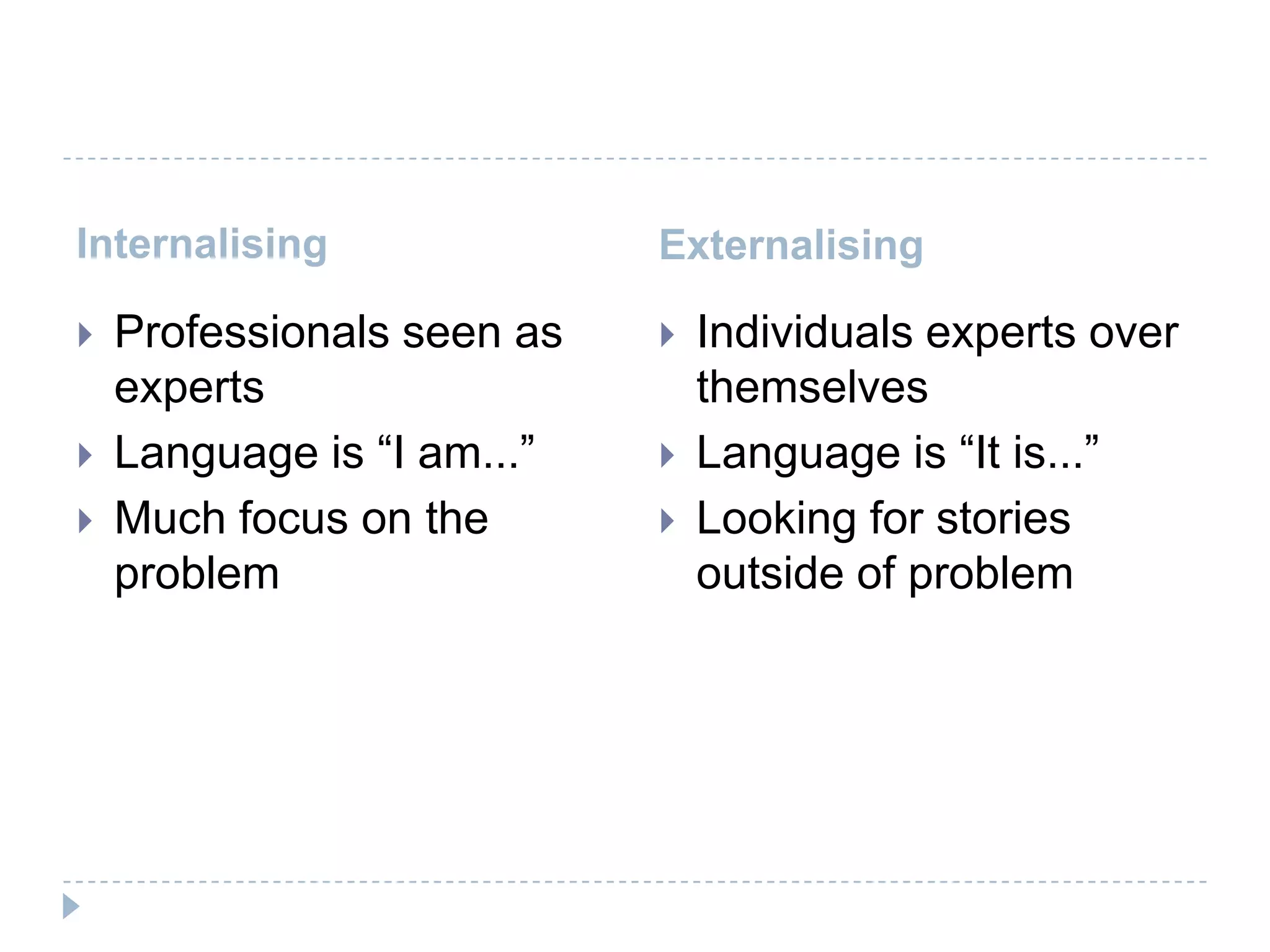

This document provides an overview of narrative therapy techniques for addressing addiction issues. It discusses externalizing problems to give clients a different perspective, deconstructing dominant problem-saturated stories through questioning, and identifying alternative storylines and exceptions. The goal is to separate a client's identity from the problem and view it as external to encourage new narratives. Re-authoring involves linking life events differently according to alternative themes and hopes rather than the problem. Re-membering conversations invite clients to revise which people and experiences are important memberships in their life stories.