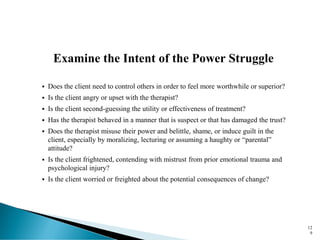

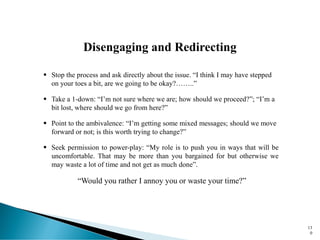

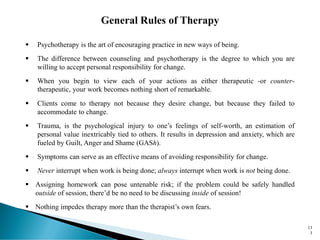

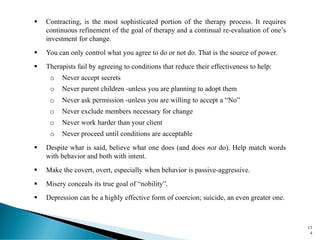

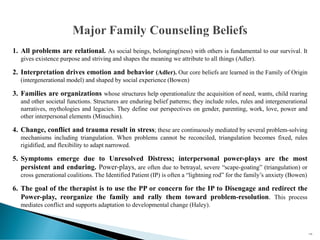

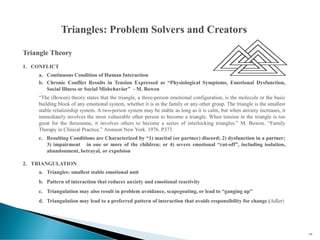

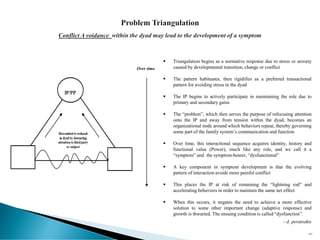

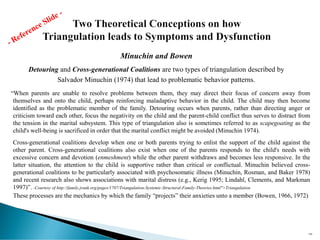

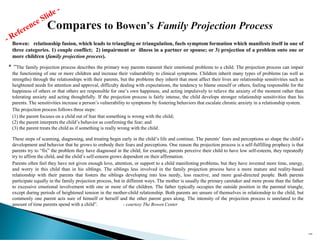

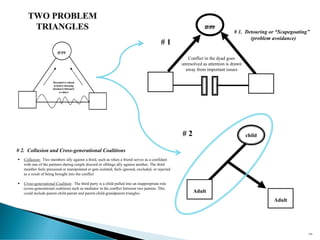

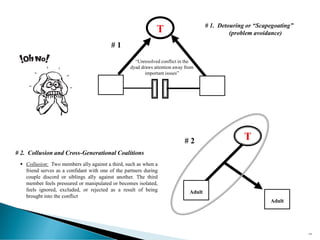

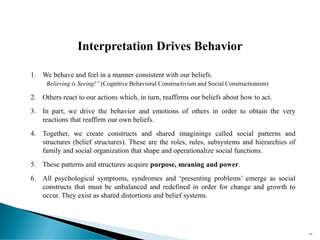

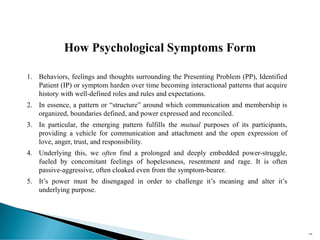

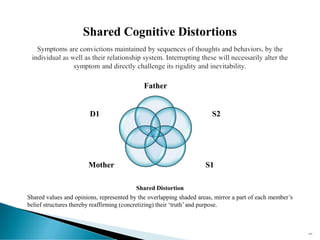

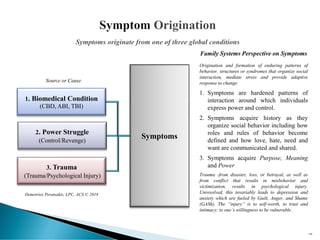

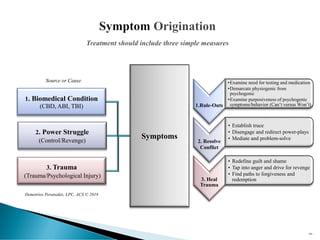

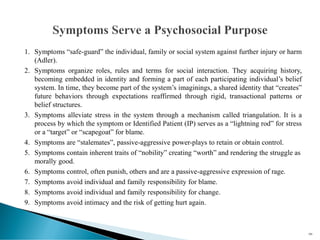

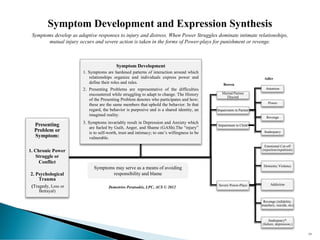

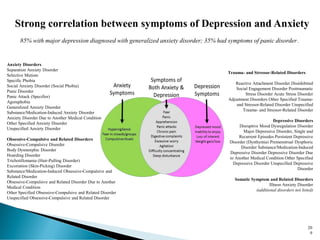

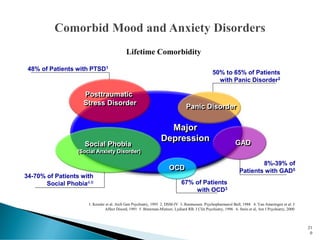

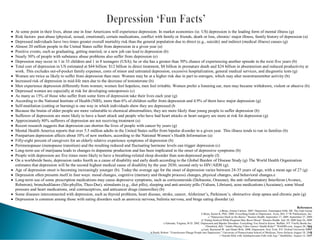

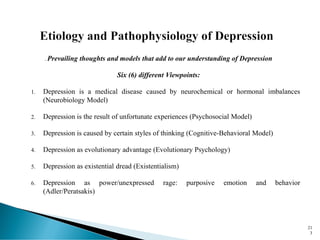

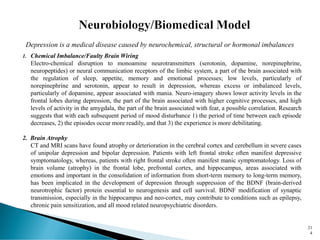

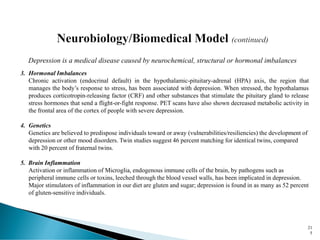

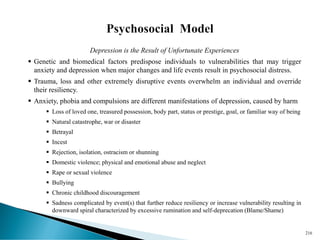

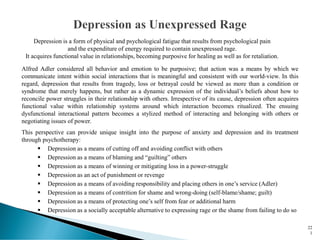

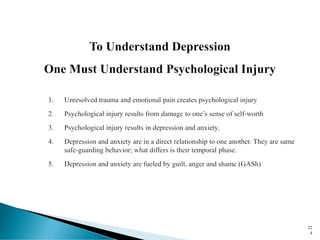

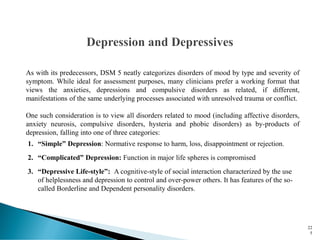

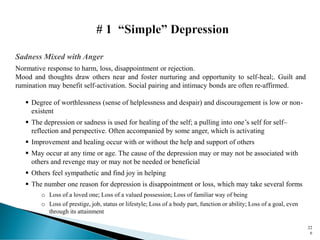

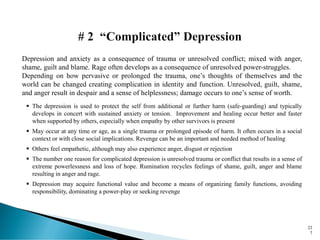

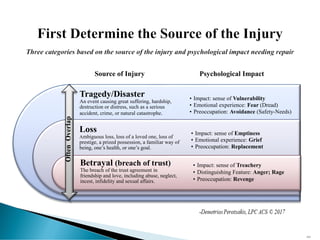

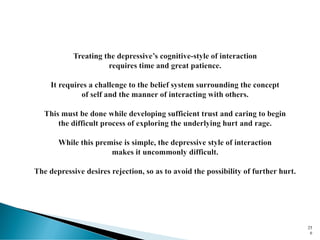

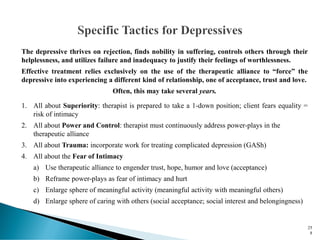

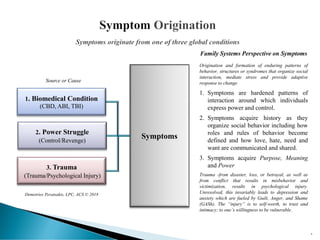

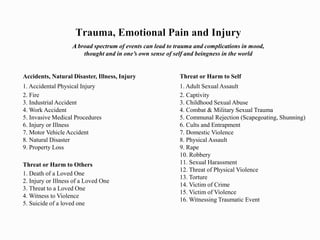

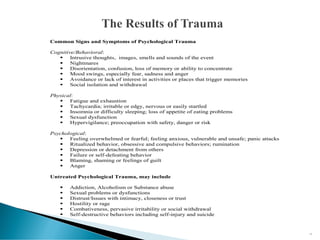

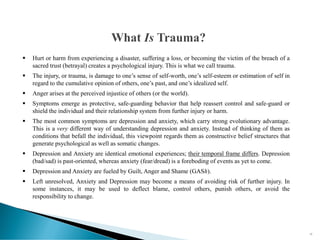

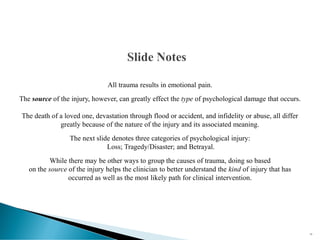

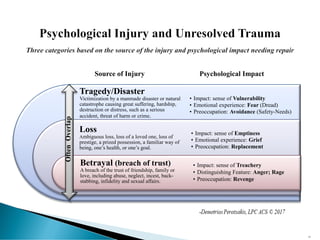

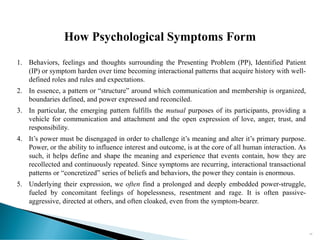

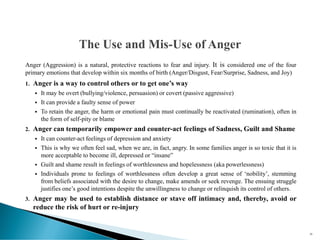

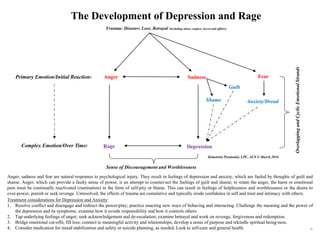

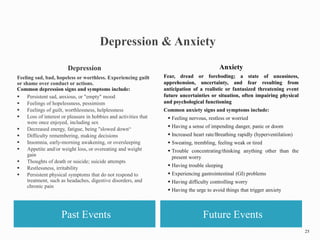

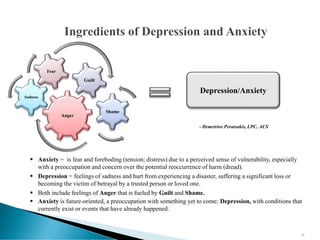

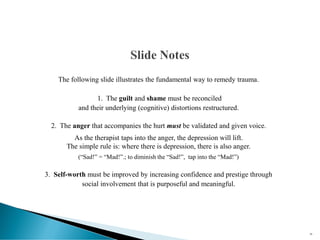

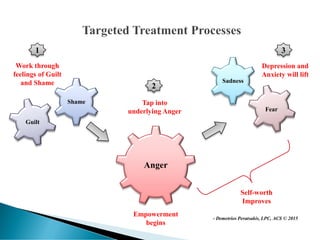

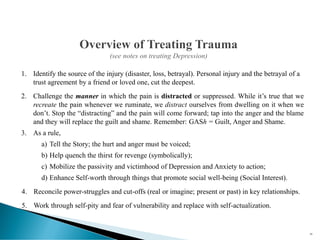

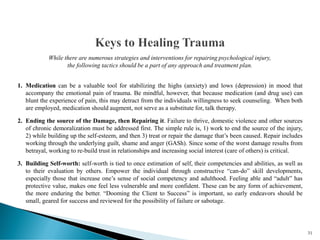

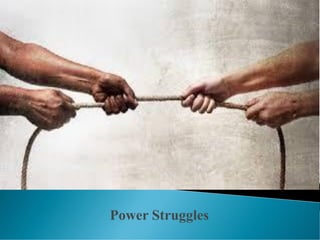

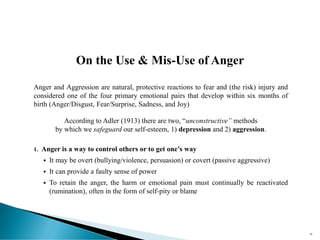

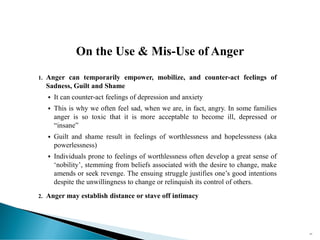

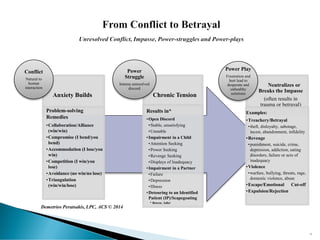

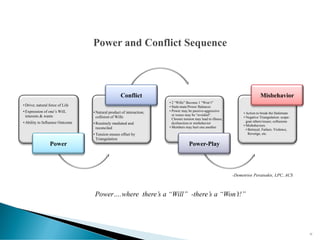

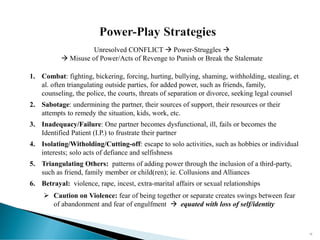

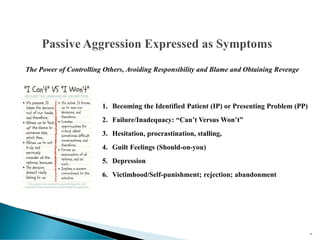

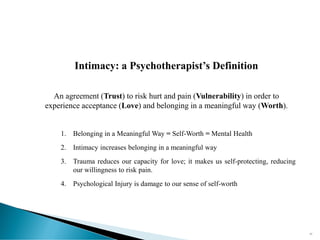

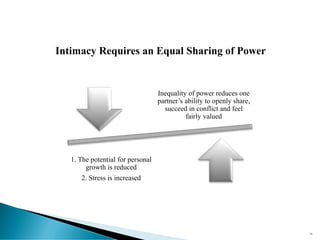

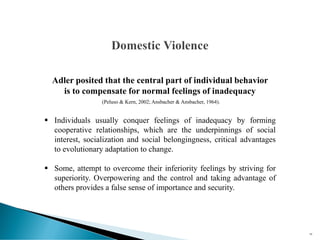

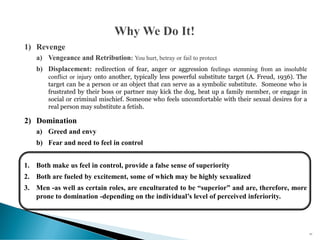

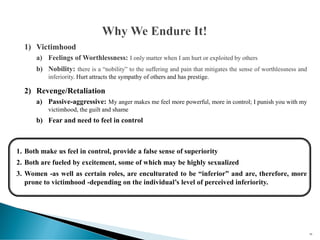

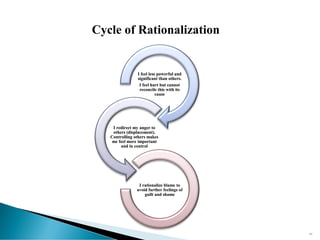

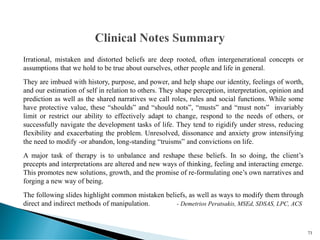

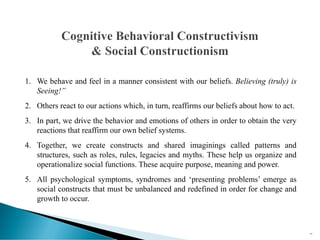

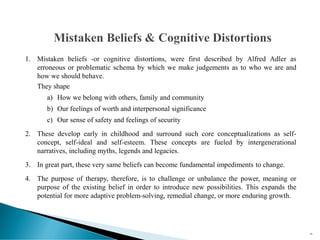

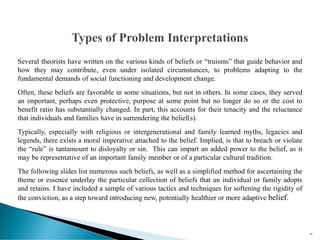

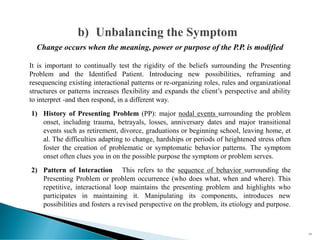

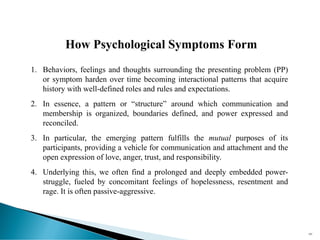

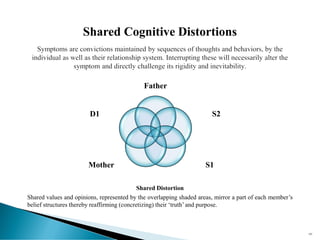

The document discusses the philosophy and practice of clinical outpatient therapy from the perspective of Demetrios Peratsakis. It provides an overview of Peratsakis' training and mentors in family therapy and Adlerian approaches. The document also outlines a psychosocial, constructivist perspective on the development of psychological symptoms, viewing them as protective belief structures that arise from trauma, power struggles, or medical conditions. It discusses how symptoms acquire meaning, purpose, and power over time through hardened interaction patterns. Unresolved trauma can result in depression and anxiety, which are fueled by guilt, anger, and shame and left untreated, may be used to control or punish others.

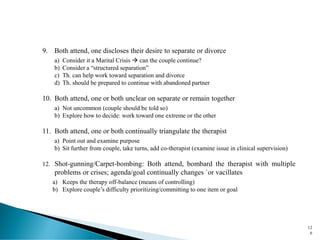

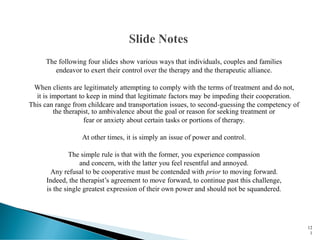

![1. Not talking

2. Not following advice or

suggestions

3. Non-disclosure [Selective

disclosure] or not answering

questions

4. Taking notes or recording sessions

5. Coming late or leaving sessions

early

6. Non-payment/Non-compliance

with Required releases and

Paperwork

7. Stalking, Threatening, or

Intimidating

8. Provocative or threatening clothing

9. Change seating or other office

arrangements

10. Provocative or threatening language

11. Use of language

12. Belligerence and Rage

13. Dominating the conversation

14. Inappropriate touching, hugging, etc

15. Inappropriate gifts

16. Inappropriate or offering incentives

17. Acting seductively, coy or unduly

vulnerable

12

2

1-17: “Client Expressions of Power in the Therapeutic Alliance” -by Ofer Zur, P.D.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/advancedmethodsinclinicalpracticefeb2020-200222015339/85/Advanced-Methods-in-Clinical-Practice-feb-2020-122-320.jpg)