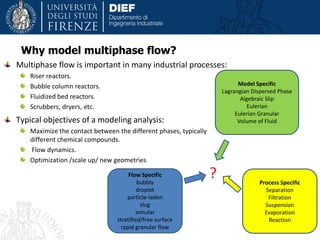

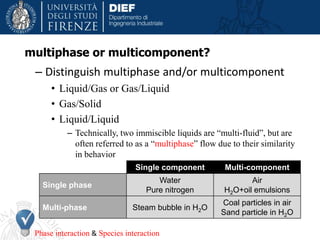

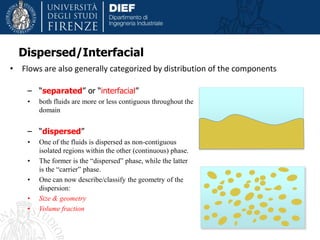

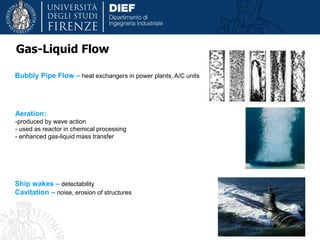

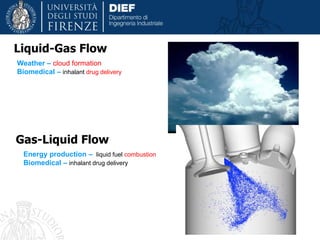

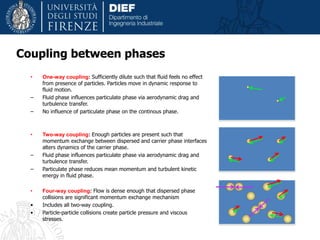

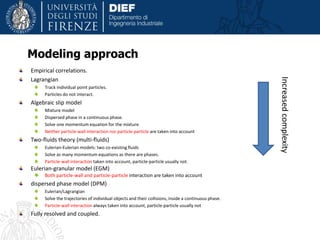

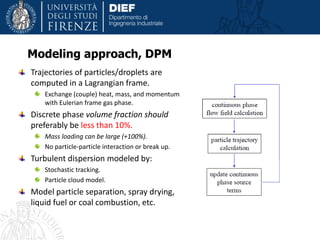

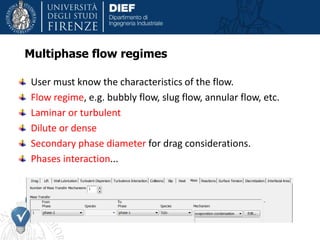

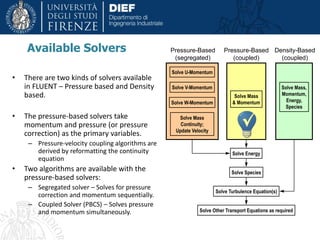

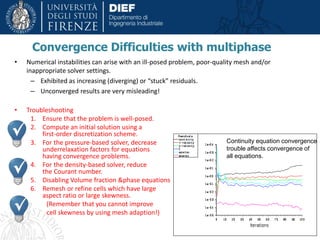

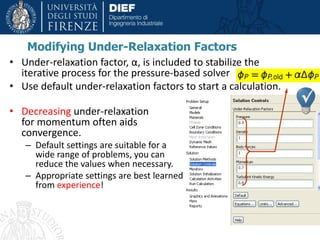

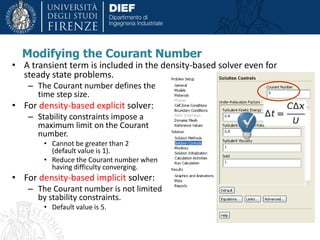

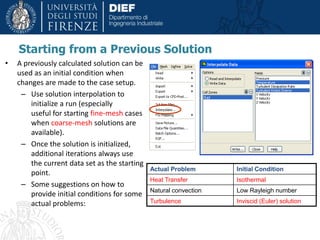

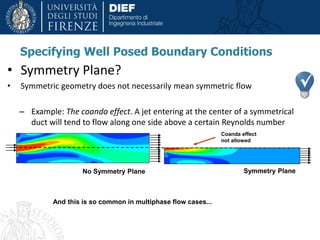

This document discusses modeling and simulation of multiphase flows using computational fluid dynamics (CFD). It begins with definitions of multiphase flow and discusses important types including bubbly, droplet, particle-laden, and annular flows. The document then provides tips on multiphase simulation including choosing appropriate modeling approaches such as Lagrangian, Eulerian, or volume of fluid methods depending on the problem. It concludes with discussions of challenges such as convergence difficulties and appropriate solver settings and techniques to address these challenges.