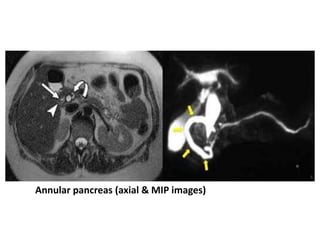

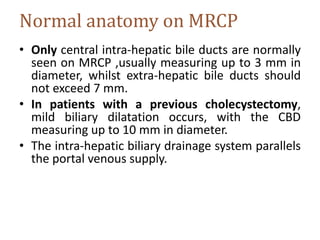

This document provides an overview of the normal anatomy of the biliary tree and gallbladder as seen on magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). It describes the branching pattern of the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts as well as the insertion of the cystic duct. It also discusses the normal appearance, positioning and drainage pathways of the gallbladder and pancreatic duct. The document outlines the MRCP technique including sequence types and preparation steps. It highlights some common anatomical variants and pitfalls that can be seen on MRCP images, such as artifacts related to technique and reconstruction.