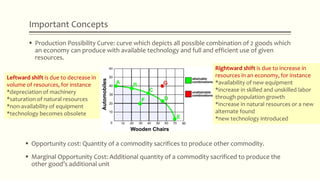

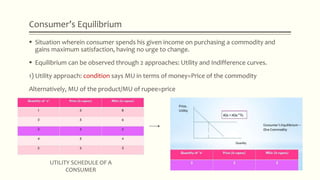

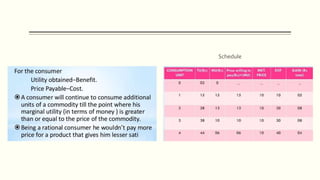

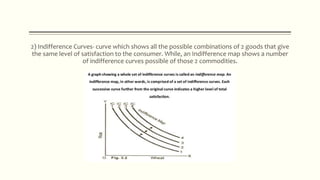

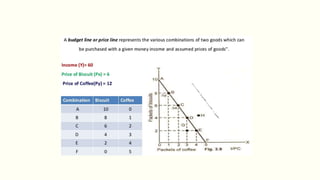

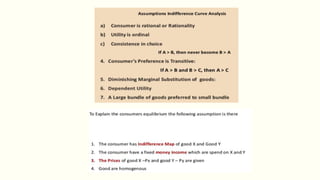

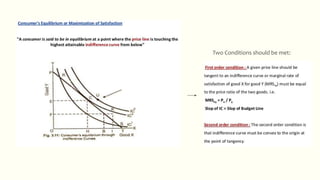

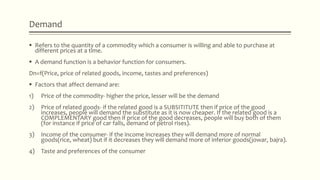

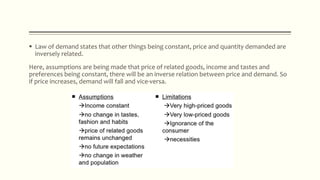

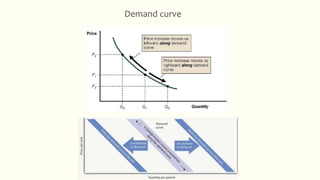

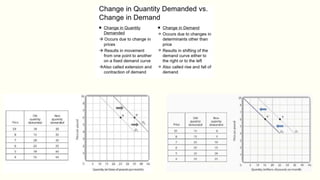

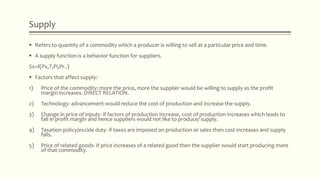

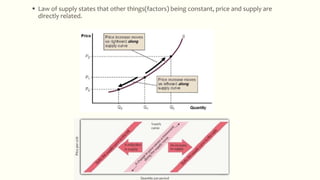

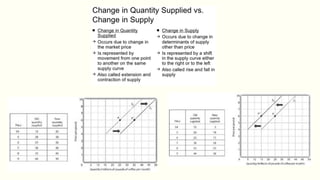

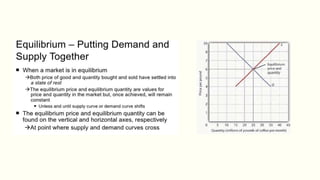

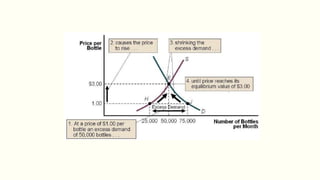

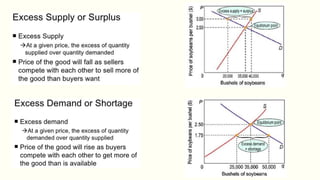

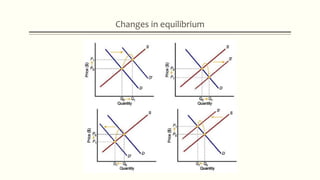

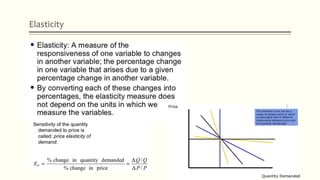

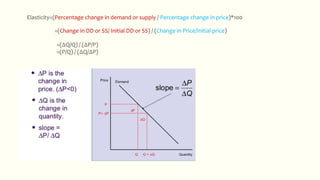

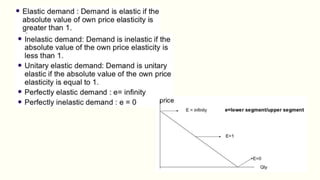

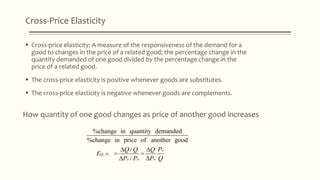

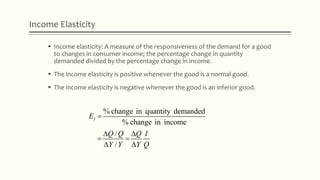

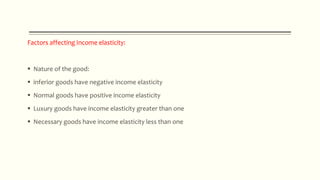

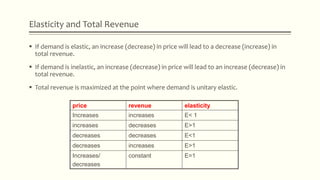

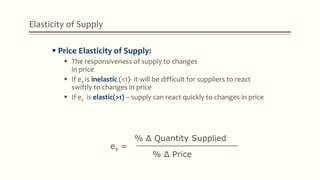

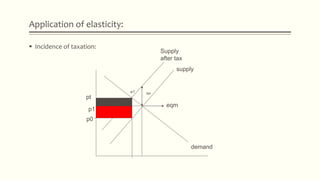

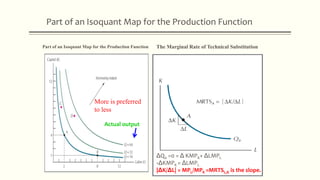

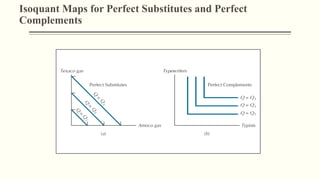

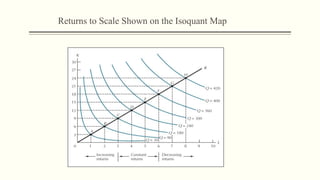

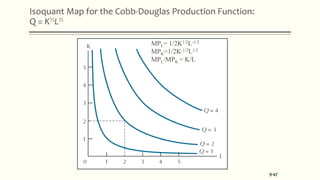

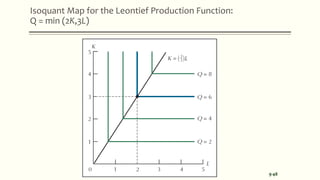

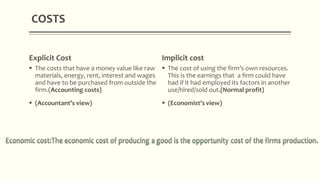

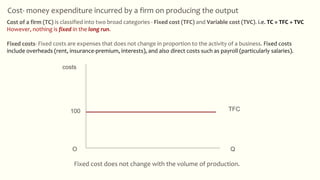

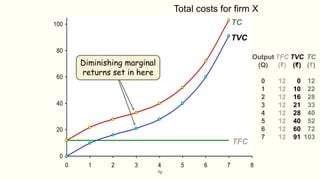

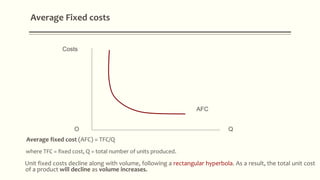

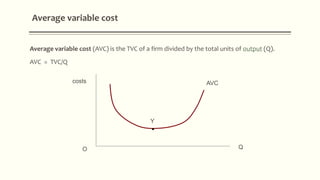

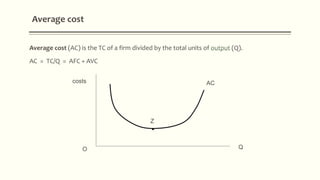

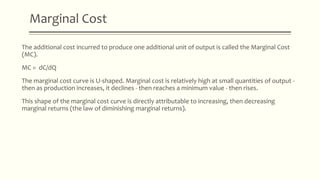

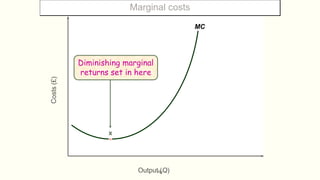

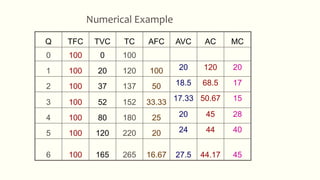

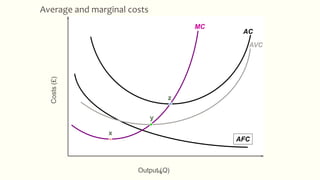

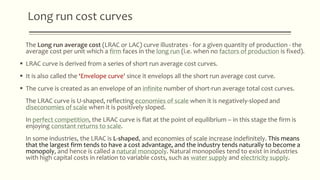

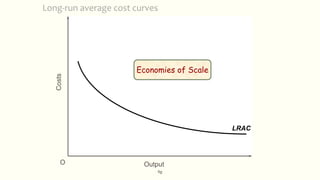

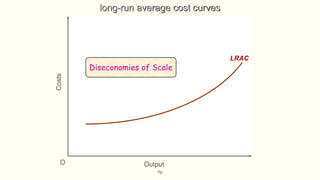

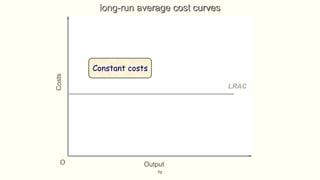

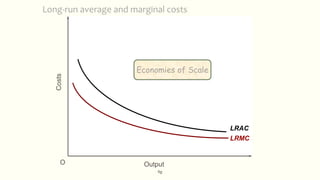

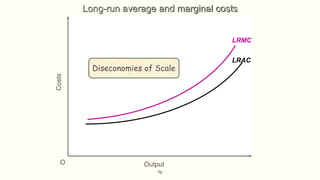

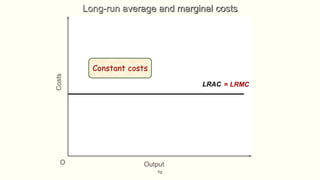

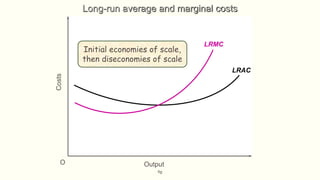

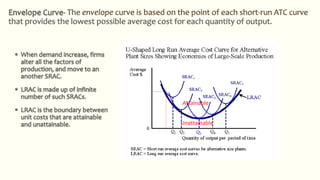

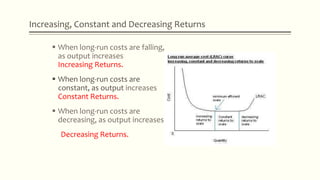

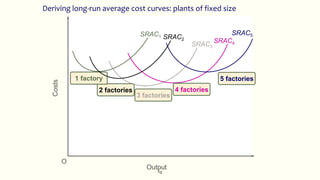

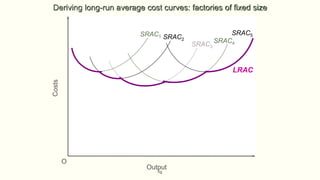

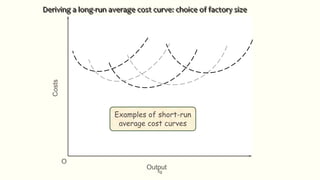

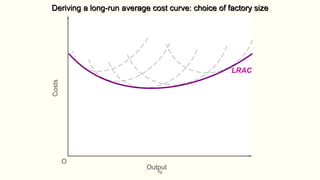

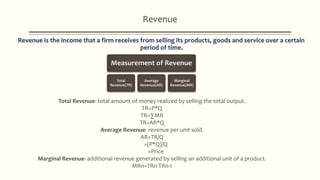

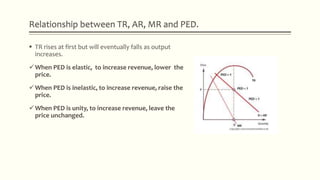

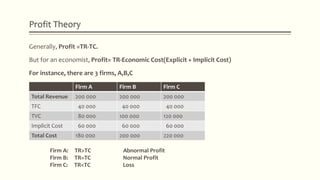

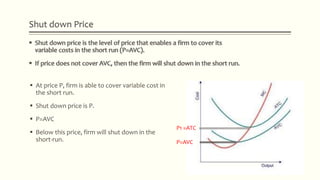

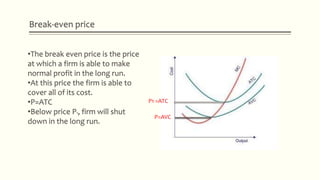

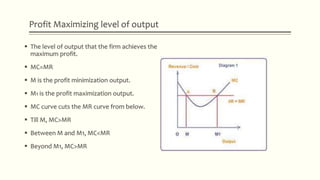

The document provides an overview of microeconomics, focusing on the decision-making processes of households and firms amidst scarcity. It distinguishes between microeconomics and macroeconomics, delving into key concepts such as production possibility curves, utility, demand and supply functions, elasticity, production functions, and the costs associated with production. Additionally, it discusses the implications of economic theories on consumer behavior and market equilibrium.