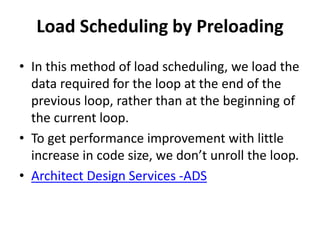

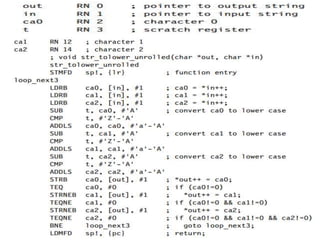

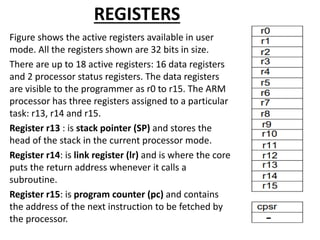

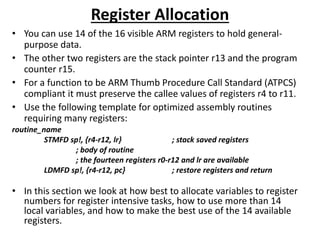

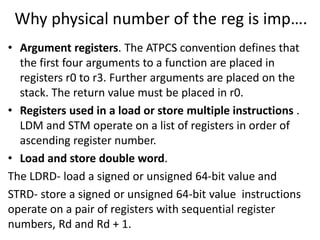

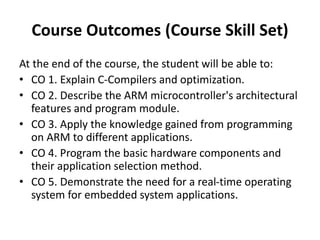

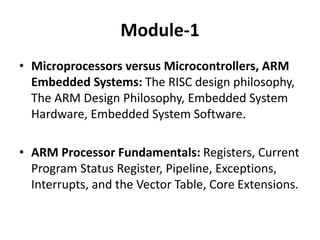

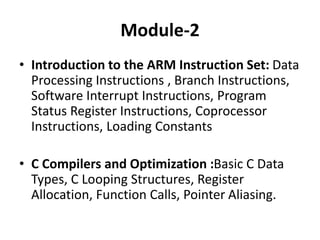

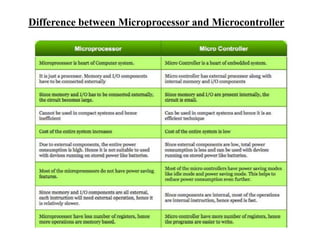

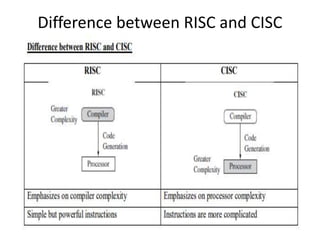

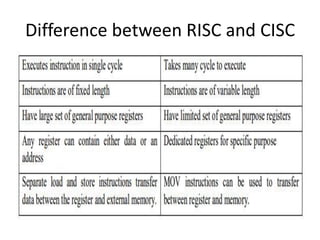

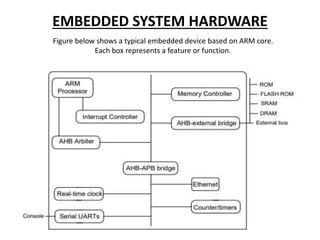

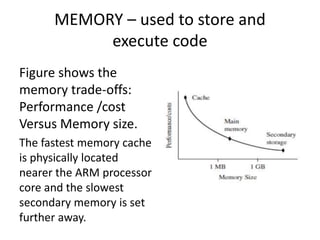

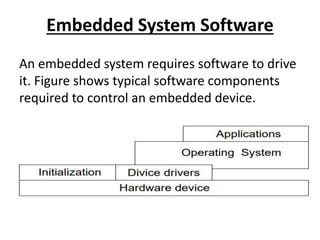

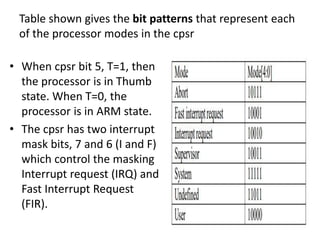

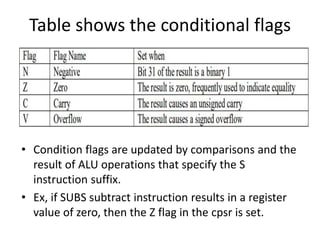

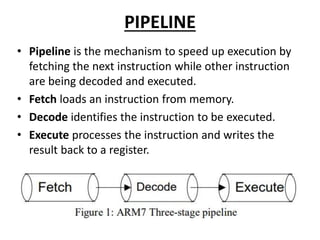

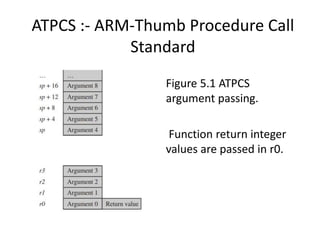

This document provides an overview of microcontrollers and embedded systems using ARM architecture. It discusses the differences between microprocessors and microcontrollers, as well as RISC and CISC designs. The ARM design philosophy focuses on low power consumption. An ARM-based embedded system typically includes an ARM processor, controllers, peripherals connected via an AMBA bus. Software includes boot code, an operating system, device drivers, and applications. The ARM instruction set and registers are also described.

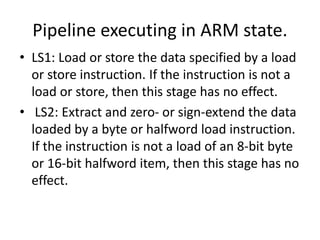

![LDR r1, [r2, #4]

ADD r0, r0, r1

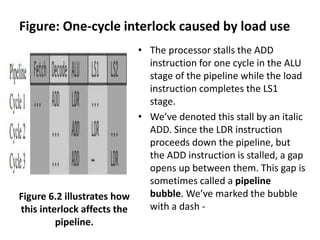

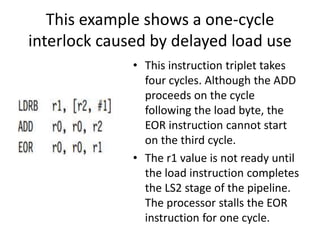

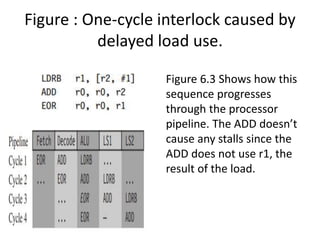

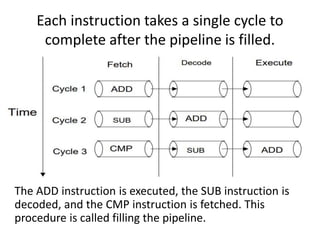

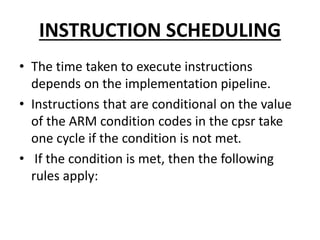

• This instruction pair takes three

cycles. The ALU calculates the

address r2 + 4 in the first cycle

while decoding the ADD

instruction in parallel.

• However, the ADD cannot

proceed on the second cycle

because the load instruction has

not yet loaded the value of r1.

• Therefore the pipeline stalls for

one cycle while the load

instruction completes the LS1

stage. Now that r1 is ready, the

processor executes the ADD in

the ALU on the third cycle.

This example

shows a one-

cycle interlock

caused by load

use.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mesppt-240209165419-05f9fae0/85/MES-PPT-pptx-83-320.jpg)