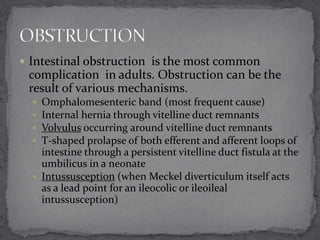

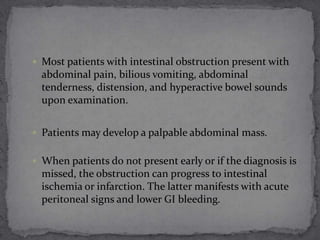

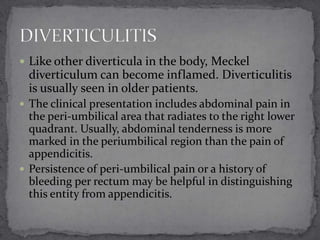

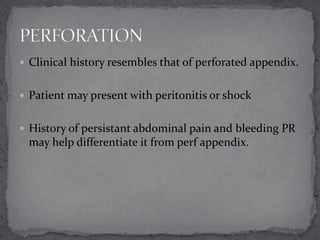

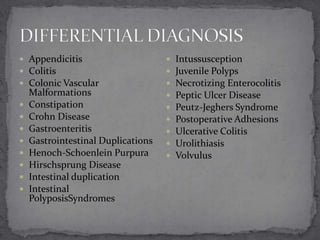

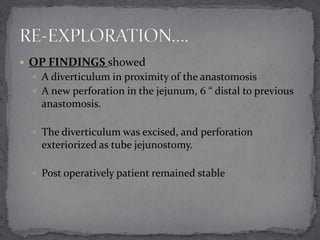

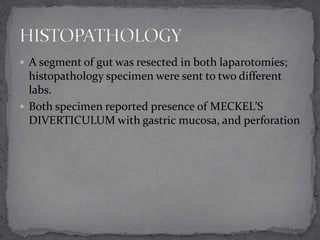

This document describes a case of a 12-year-old female who presented with abdominal pain and signs of peritonitis. She underwent an exploratory laparotomy which revealed a Meckel's diverticulum with gastric mucosa and a jejunal perforation. She had a complicated postoperative course requiring a second surgery. Meckel's diverticulum is a common congenital abnormality caused by incomplete vitelline duct obliteration. It can contain heterotopic gastric or pancreatic mucosa and commonly presents in children with GI bleeding. Surgical resection is often required for complications like perforation or obstruction.

![ Meckel diverticulum (also referred to as Meckel's

Diverticulum) is the most common congenital

abnormality of the small intestine; it is caused by an

incomplete obliteration of the vitelline duct (ie,

omphalomesenteric duct).

Although originally described by Fabricius Hildanus

in 1598, it is named after Johann Friedrich Meckel, who

established its embryonic origin in 1809.[1]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/meckelsdiverticulum-140118051243-phpapp02/85/Meckel-s-diverticulum-12-320.jpg)