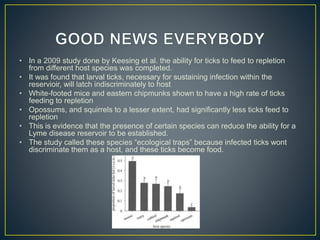

This document summarizes the history and ecology of Lyme disease. It discusses how the disease was discovered to be caused by Borrelia burgdorferi transmitted by blacklegged ticks. It describes the tick life cycle and how climate influences tick ranges and disease establishment. While climate change may expand tick habitat, many factors determine Lyme disease occurrence. Some host species may reduce disease transmission by not allowing ticks to feed to repletion.