This document is an introduction to F.W. Newman's Mathematical Tracts from 1888. It provides an overview of the contents which include discussions on the bases of geometry, primary ideas of spheres and circles, definitions of straight lines and planes, parallel lines, and volumes of pyramids and cones. The first tract focuses on ratios of incommensurable quantities and introduces the concept of variable quantities that increase uniformly to establish ratios. It then discusses primary geometric ideas including spheres, circles, poles, and parallel circles on a sphere. Finally, it defines straight lines as that which connects two points evenly and introduces the concept of a plane.

![MATHEMATICAL TRACTS

PAET I.

BY

F. W. NEWMAN, M.RA.S.

EMERITUS PROFESSOR OP UNIVERSITY COLLEGE, LONDON

HONORARY FELLOW OF WORCESTER COLLEGE, OXFORD.

Cambridge :

MACMILLAN AND BOWES.

1888

[All Rights reserved.]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/30cf3adf-bd3e-433b-af66-df604dc7e0cf-160316032321/85/Mathematical_Tracts_v1_1000077944-7-320.jpg)

![WHEN PROPORTIONAL. 15

the proportionatelengthscounted alongthem are also proportionate

lines.

If the arc NP = arc LM, add MN to both, then arc PM = arc NL.

This enables us to exchange the second and third terms in the pro-portion,

agreeablyto the process called Alternando. Also the arc

PL = PN+NL=ML+NL. Hence if we count from L, and call

arc LM" m, arc LN =

n, arc LP =

p, the test of necessary direction

is p = m + n.

The simplestcase is,when the four proportionalsbecome three

by the second and third coalescing,as if M and N run togetherin Q.

Then if arc ZQ = arc QP, we have OL : OQ= OQ : OP. If further

arc PR = arc PQ, then OQ : OP = OP : OR] and so on.

4. Apply now this to the case in which the arcs PQ and QL are

both quadrants.Then OQ is the mean pro-portional

between OL(= 1) and OP=(" 1).

The received symbol for a mean proportion

is V, as in OQ = *JOP .

OL. Here then

OQ =

V(- 1 .

1)= V- I- This is only a fol-lowing

out of analogy with the symbol;

though, previously,V expressedthe mean

proportionbetween numbers, or perhapslengths,without cognizance

of direction.

Now, our first care must be, to inquirewhether V~ as a symbol

of direction,has the same propertiesas when it operates on a pure

number.

First,in combining factors,the order is indifferent,as ab = ba,and

a .

(1)= a = 1 .

a. We ask, does V~ fulfilthis condition? Evidently,

a. ^-1 =

^-1. a, each measuring the lengtha, directed alongthe

perpendicularOQ. Similarly

Next, repeat */-" We had OQ = OL*/-I or "/-!. OL. Also

OP=J-I.OQ, because QOP = 90", .'. OP = V~ 1 .(V -

1 "

OL).

But OP = - OL or -

1 .

OL. Evidentlythen V -

1 .

V - 1 is equi-valent

to - 1. This further justifiesthe change of

-j"^

to -*J-.

5. But a new difficultyarises in adding unlike quantities,i.e.in

connectingthem by +. If along radii m and n we have two lengths

a and b ,

what meaning can we attach to am + bj. This urgently

needs explanation.It may seem that the symbol+ (plus)receive](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/30cf3adf-bd3e-433b-af66-df604dc7e0cf-160316032321/85/Mathematical_Tracts_v1_1000077944-23-320.jpg)

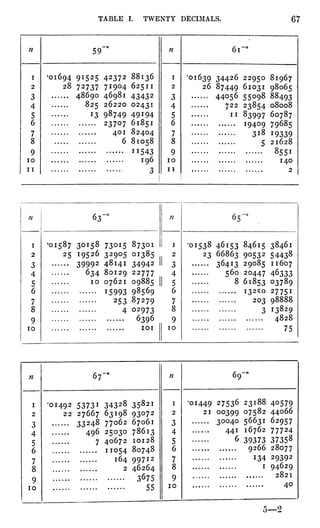

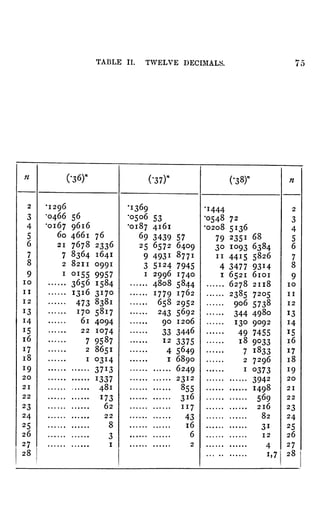

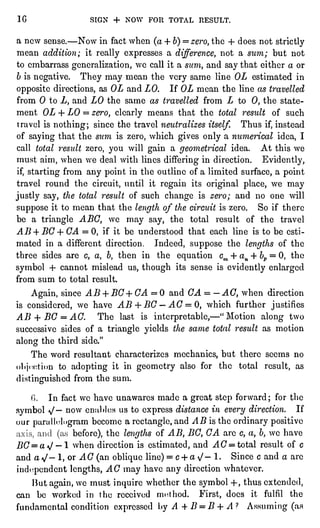

![TRACT III.

ON FACTORIALS.

SUPPLEMENT II.

Extension of the Binomial Theorem.

1. THE following appeared in Cauchy's elementary treatise, as

early, I think, as 1825, but without the new Factorial Notation, which

adds much to its simplicity. Boole writes #(2) for x (x - 1), #(3) for

a? (a;-1) (2?-2), and xw for x(x- 1) (a?-2) ...

(x- n+ 1), whence

a)(n+l]=

x(n)

.

(x "

n). Better still it is, to place the exponent in a

half-oval, since a parenthesis ought to be ad libitum. I

propose

which are quite distinctive. Then the Binomial Theorem is

In this notation 1

.

2

.

3

.

4

...

n or n (n - 1) ...

2

.

1 is n^. Guder-

mann for this has n ;

but (n " 1)' is less striking to the eye

than

n, In "

1 introduced by the late Professor Jarre tt. This exhibits in

the Binomial Theorem its general term, by

1 + xn = + n

.

+ ...

+ n

.

+ .

of course x^L" is equivalent to simple x.

The Exponent (of a power) is already distinguished from an

Index. In a Factorial x^ for x (x -

1 ) (x - 2) . . .

(x - r - 1) one may

call r (which must be integer) the Numero, as stating the number of

factors.

2"2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/30cf3adf-bd3e-433b-af66-df604dc7e0cf-160316032321/85/Mathematical_Tracts_v1_1000077944-27-320.jpg)

![26 WITH A NEGATIVE NUMERO

that when x is numericallyless than 1,with n indefinitelyincreasing,

the series 1 + x + a? + . . .

-f xn tends to the limit

n

l "

x

After this it quicklyfollows (by Cauchy'sprocess now perhaps

universal),from Binomial Theorem with n positiveinteger,that

(1"1 + -J with n infinite,has for limit

17

+^=2-7182818...

which we call e, and that f1 + -J has for limit

which also = ea. On this we need not here dwell : but it will

presentlybe assumed. Now let us propound

Factorials with NegativeNumero.

6. Analogy suggeststo define x^ as meaning"; --

-^

: of course

x x ~H 1}

x^ will be identical with x~l. Then x^ will stand for

and x^" for [x(x+ 1)(x+ 2) . . .

(x + n -

I)]"1.

Hence x^J = (x + n)~l.

#O.

Now x^ = (x H-l);*;^,

and when x is " 1,we have, in descendingpowers

x^ = x~* " x~3 + x~4 - x~b 4- etc.

Also x^ = (x+3y.x^"

of the two factors here on the right,each can take the form of

a series descendingin powers of x. So then their product,the

"liivalentof x^l". By like reasoningwe claim a rightto assume

with coefficients independentof x,

x^ = A;x-n-l-A"1x-n-z+An,x-n-3-etc.......... (a),

and our task is to discover the coefficients when n is given.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/30cf3adf-bd3e-433b-af66-df604dc7e0cf-160316032321/85/Mathematical_Tracts_v1_1000077944-34-320.jpg)

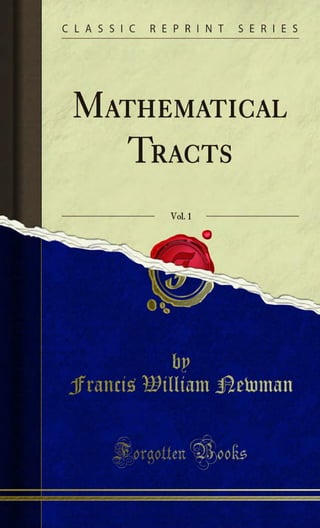

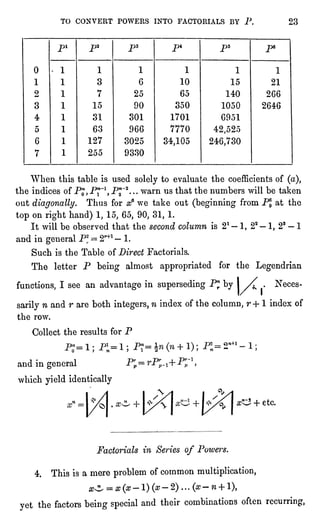

![THE TABLE OF P SUFFICES. 27

First make n =

1,

But from the series alreadyobtained for x^ we see that every

coefficient of the last is 1 ; or in generalAlr=I. This givesthe first

column of our table. Also universallyAn,obviously= 1 ; which fixes

the firstrow of the table.

Next, multiplyequation(a)by (x + n),and you get

s~M 2" etc. ...

+ A"x~n~r+ ..

But in (a)we may write n for n + 1, which gives

x^ =

x-n-A^lx~n~l+... "A?~1x~n~r+ ............ (c).

Now (6)and (c)must be identical,hence

Al=n + Arl=nAl+Ar

and generally A^nA"^ + Anr~l.

But this is exactlythe law of P in Art. 3, only there we had r, p for

what are here n, r. Now as the first row and first column are here,

as there,unity,and the law of continuation the same, the whole table

will be the same, and we may write P of Art. 3 in place of this A.

Thus we get

x" = x~n -

Pr V"-1 + PJ-V""1 -

P3n-Vn'3 + etc. . . .

with the same values of P as before. But in the last equationwe no

longer take the P's diagonally,but vertically,down the column, as

the same upper index (n "

1) above every P denotes ; thus

T7 - etc. . . .

To verify,multiplyby x + 2. But for convergence x ought to

exceed 2. So

f

4

- 90af5 + etc. . . .

and for convergence, x oughtto exceed 3. Evidentlyin the series for

,

x ought to exceed (n"

1).

7. Assume now the Inverse Problem, to developx'n in series of

Factorials.

With unknown coefficients B independentof x, we start from

x-n-l = x^+Btx^J + ]%x^J+ ...............

(a).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/30cf3adf-bd3e-433b-af66-df604dc7e0cf-160316032321/85/Mathematical_Tracts_v1_1000077944-35-320.jpg)

![28 FOR THE INVERSE PROBLEM, Q SUFFICES.

Multiplythe lefthaud by x, and the successive terms on the right

by the equivalentsof x, viz.

(x + n)-n, (a-+ n + l)-(w + l)f(aj+ n + 2) -

(n + 2),etc.

Observe that (x+p) a,'-*""= x(~p)"

-...'

But in (a)we may write n for n + 1,which gives

^J+...+Bnr-l.x^r+ ...... (c).

Identify(6)with (c),

.-. J3T=n + "rl;

and generally Bnr=

(n + r -

1)B*^ + Bn/1;

the same formula as for Q in Art. 4, only n and r here standingfor

what there was r and p. Also since .Bj=l, the top row is unity,

here as there.

We may further prove that the first column of our J5's is the

same as the firstcolumn of the Q's. For

Multiply by x on the left,also by (x + 1) "

1, (x + 2) -

2,

(x+ 3)"

3, for the successive terms on the right; then

Obviouslyx~l = x^ ; and the other terms must annihilate them-selves,

making ^-1=0; B -

2B = 0 ; B -

SB] = 0 ; etc.,

or B = I, ^ =

2^ = 1.2;

JBJ=3B;=1.2.3, and Bln=l .

2 .

3 ... (n- l)n.

Thus B=Q, BI =

Q13)etc. exact. Therefore the B table is the

same as the Q table throughout.

Here also we take the Q's vertically,to obtain x~n in series of

factorials as x~4 = x^ + Ga;^ + 35^ + 225#^ -f etc.

In generalx~" = x^ + Q^x^ + Qrlx^~? + ...

+ Q;*1.^C^r + etc.;

but specialinquiryis needed concerningconvergence. Apparently

it converges more rapidlythan

x*+(js -hi)'2+ (a+2)-f+ etc.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/30cf3adf-bd3e-433b-af66-df604dc7e0cf-160316032321/85/Mathematical_Tracts_v1_1000077944-36-320.jpg)

![THE TABLE OF P AGAIN SUFFICES. 31

Put n + p -

r, to identifythis term with our previousMr .

xr ;

.'. M =

*5="

w + l.w-f 2-. 7i + 3 ... (r-1) .r'

Cn+l

so that

^rr=n+ 2tn-^3~1r__l r

with one lessfactor in denomina-tor:

but when both n and r in Mr are increased by 1,r -

n undergoes

no change; and N ^

= r~n

" + 2.n + 3... r" l.r.r-hl'

Introduce these values into (a)and multiplyby

Change r -

n to p and n + 1 to n, .'. Cnp=

Cnp~l+ nC;^ ; the same

law as for the P's in Art. 3.

Also when n =

lt

But we assumed as equivalent

01* OX cx_ ex

2 "^S.S^S.S.^"1" "t"2.3...(r+ l)

which identifies (7Jwith 1,for all values of r. Just so Plr= 1 in its

first column. Also evidently"7j=

l; justas PO=!" in tne whole

first row. Thus, with firstcolumn and firstrow identical with those

of P and the same law of continuation,the whole table is the same.

Finallythen we obtain

-iy pj.a?

= i+

in which the increasingnumerators are pulleddown by increasing

denominators.

The generalterm may be written n^ . Pnp.

xp, or equally

(n

[The course of analysishere pursuedforestalls that of A" .

Or to

the learner.]

Thus

"?

+ l n + 1 .

n + 2 n + 1 .

w + 2 .

n + 3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/30cf3adf-bd3e-433b-af66-df604dc7e0cf-160316032321/85/Mathematical_Tracts_v1_1000077944-39-320.jpg)

![PROBLEM OF [log1 + a?]".

Hence 2AZ = 1, 3AZ = 1, = 1,or in generalAn = -

Finallythen,log(1+ y)=

y -

y^+ Jy8-

y*+ etc. . . .

while y2" 1.

N.B. This furnishes the means of computing logarithmsin

Elementary Algebra,before knowing the Binomial Theorem with

negativeor fractional exponent. If Differentiation or "Derivation,"'

as far as "f"(x)" xn, "fi(x)= nxn~l,be admitted,this equationat once

proves that when ""(z) means log(z),""'(z)= -

: a process which

eases the next Article.

10. PROBLEM. To develop[log.

1 +x]nin a series of powers of x.

That this is possible,when x2 is " 1, the precedingArticle shows.

We may then assume, with unknown coefficients X? ,

A"

,

A* . . . depend-ing

on n alone,where the upper index is not an exponent,

-

2 ...

w + r

+ etc

If = uny dz-nun~ldu, and

(a).

[It is

hardlyworth while to disguiseDifferentials by a more elaborate and

tedious Algebra.]

Differentiate both sides of (a),then dropthe common factor dx :

hereby,

n (log1 + XT'*_

-

Multiplyby 1 + x, and divide by n,

.-. (logf+^r1 = *"* -

*? "

;r

+ ^i

fe'tc----

-etc.

etc.

etc.

(6).

N.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/30cf3adf-bd3e-433b-af66-df604dc7e0cf-160316032321/85/Mathematical_Tracts_v1_1000077944-41-320.jpg)

![LINEAR FUNCTIONS. 37

Observe,if the equationsbe presentedin the form

aix + ty + c1= 0 ; a2x + bjj+ c2= 0 ;

this is equivalentto changing the signsof c1 and C2, which does not

affect C, but exactlyreverses the signsof A and B. Previously

we had

(x : A) =

(1 : C) =

(y : B),

or (x :

y : 1) =

(A : B : C) =

But from the two new equationsa:x + b$ + c^z=

0| you get

V + ty + c/

=

0|

= OJ

6. c. ci ai

C2 a2

a? : y : z =

in circular order.

We may also present the solution as follows :

M,

2. Simple equationsare often called Linear, by a geometrical

metaphor. If a quantityw is so dependent on x, y, z... that how-ever

the values of these may vary, yet always u = ax + by + cz -K . .

(where a, b,c... are numerical),then u is called a linear functionof

#, y, #... its constituents. [One might have expected u to be called

a dependentor a resultant : but for mysterious reasons of their own,

the French have adopted the strange word function ; and it cannot

now be altered.] It is convenient now to set forth a few properties

of linear functions. We here suppose the function to have no abso-lute

(constant)term.

I. To multiplyevery constituent by any number (m),multiplies

the function by that number.

[For,if u = ax + by+ cz+..., then

mu = amx + bmy + cmz +....]

II. If two linear functions have the same number of consti-tuents

and these have the same coefficients [as U=ax](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/30cf3adf-bd3e-433b-af66-df604dc7e0cf-160316032321/85/Mathematical_Tracts_v1_1000077944-45-320.jpg)

![T.EMMAS OX LINEAR FUNCTIONS.

Ut =

a.rt-f byi

4- cz{]; you will add the functions if you join the

constituents in pairs[forhere

U+l = u (./.-+ a-J+ b (y + y t)+ c (s+ *,);

whatever the number of constituents].

3. Observingnow that a M

b N

or aN " bM is a linear function

of X and J7",we see that to multiplya column MX by m multiplies

the function by m. Or ja, mM =

m a M .

Ib, wX b N

The same is true if we multiplya row ; for we may regard a and

M as the variables and b and N as constant ; then

ma, mM = m

b, X

This leads to the remark, that our function ought to be called

superlinearrather than linear ; for it is open to us to suppose con-stituents

alternatelyconstant or variable.

4. Next, by making a column or row binomial, we can some-times

blend two superlineartablets into one. Thus

a M

b N

A x

B y

G x

"" y ,

havingthe second column the same, yield,

(A y -

Ex) + (Cij- Dx )=

(A + C )y -

(B + L) x = A +"7,

y

Here the column which was in both, remains as before,but the

other columns are added and make a binomial. Evidentlythe same

process holds,if a row, instead of a column, is the same in both.

Conversely,when a givencolumn is binomial, we can resolve the

tablet into two tablets ; and when each column is binomial,we can

resolve the tablets into four.

Thus A+x, C .1, C! + z

B, D + v

x, C + z

y,

by " firstprocess. By a second, each of these tablets becomes two,

as result,

A C

11 1"

.1

/; H

x C

'/ l" H ''](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/30cf3adf-bd3e-433b-af66-df604dc7e0cf-160316032321/85/Mathematical_Tracts_v1_1000077944-46-320.jpg)

!["1 EXCHANGE OF COLUMNS OR ROWS.

Observe,that if three binomials of V3 are expressedby

maa + H-cra4- pal

the multipliersmt n, p contain nothing of the column a1? a2, a3,

therefore V3 is linear in these three constituents. Evidentlyit is

linear in regardto any column ; as we before saw, as to any row.

9. THEOREM. Further, 7 say, To exchange rows and columns

does not alter the value of V3. In proof,multiplythe three equations

givenin Art. 7,by disposablenumbers m, n, p, and so assume m, n, p

that when the three productsare added togetherthe coefficients of y

and z may vanish. There will remain (ma^+ ?ia2-f pa3)# = 0, and as

we do not admit #=0, we have three equationsconnectingm, n,p viz.

a,m -I-a2?i+ a 3p = 01

Ji7H+ "g?l_l_])^p=o'

cjn + c.2n-f C3p =

OJ

and that these may be compatible,we need

k o,

Cl C2 "

by eliminatingm, n, p.

Here S3 is nothing but V3 with rows changed to columns and

columns to rows, retainingthe same positivediagonalaj)2c3.Every

learner will easilyfind by developingV3 and S3that theyare identical:

but there is an advantage here in generalargument applicableto

higherorders. $3= 0 and V3= 0,beingeach a condition of compati-bility

of the previousequations,must contain the same relation ofthe

constituents. S3 is a linear function of its column aj)^ ; so is V3 a

linear function of its row ajb^. But $3= 0, Fa= 0 being derivable

one from the other, there is no possiblerelation but $3=

/z V3 in

which n must be free from a^Cj. But the same arguments will prove

that p is free from a262c2,also from a3b3c3.Therefore /-t is wholly

numerical. Make 6,= 0, ct= 0 and this will not affect ft. But this

makes

and S =

M.

But that the two minor tablets are identical was implied in their

definition. Hence, on this assumptionfor bland c,, we find F3 =

A

or /Lt= l. This then is the umuersal value of /^ ur F;!=

#, in all

"". i-;.I).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/30cf3adf-bd3e-433b-af66-df604dc7e0cf-160316032321/85/Mathematical_Tracts_v1_1000077944-50-320.jpg)

![TWO PROBLEMS OF KL1MINATION.

Again,writingin the original

'(Pa;+ Q) x + R =

0]

(px 4- q)x 4- r = Oj

eliminate .r,as if P,r + Q and px + q were ordinarycoefficients. Then

Px + Q, R

px + ,

r

which expanded,gives

PxR + QR

px r q r

= 0, or PR

p r

x + QR

" r

Eliminate x between (1)and (2),which gives

that is,

the result required.

2_

= 0,

16. PROBLEM. To eliminate x from the two equations,

few;3+ Sbx* + Bex + d = 0,

ax*+2bx+c = 0.

First,multiplythe last by x and subtract ;

Compare the two last with the two equationsof Art. 15,

/. P =

a, Q = 2", R =

c, p = b, q = 2c, r = d.

Hence the elimination of x yields

a 2b

b 2c

2bc

2c d

a c

b d

2=0, or ab

b c

be

c d

= a c

b d

This is the condition of two equalroots in the givencubic.

17. By conductingelimination from three givensimpleequations

by a second process, we attain relations which were not easy to

-"niticipate.Assume the three "".jiiationsof Art. 7. Kliminatc //](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/30cf3adf-bd3e-433b-af66-df604dc7e0cf-160316032321/85/Mathematical_Tracts_v1_1000077944-54-320.jpg)