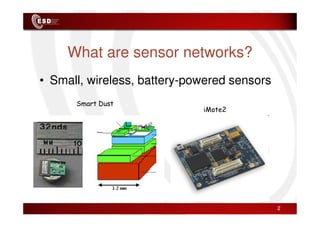

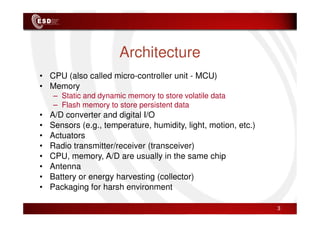

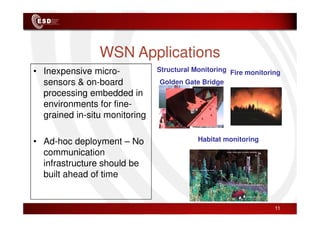

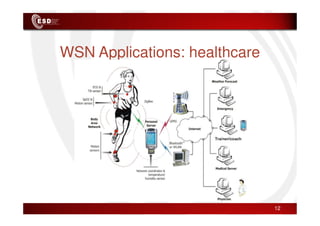

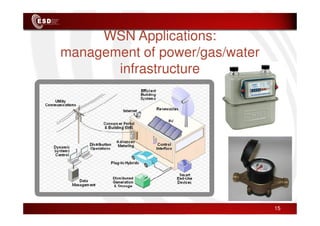

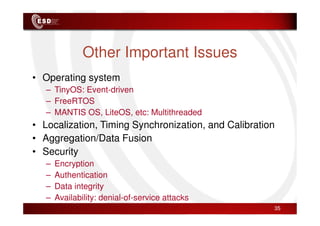

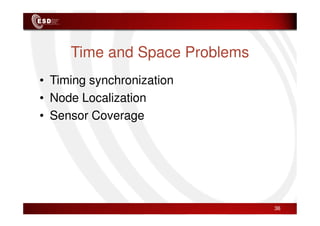

Wireless sensor networks consist of small, low-cost sensors that can monitor various environmental conditions. Each sensor node contains components like a CPU, memory, analog-to-digital converters, sensors, and a radio transceiver. Sensor networks have a wide range of applications in areas like environmental monitoring, healthcare, agriculture, and infrastructure management. However, designing efficient sensor networks presents many challenges related to limited energy, scalability, heterogeneity, self-configuration, and security.