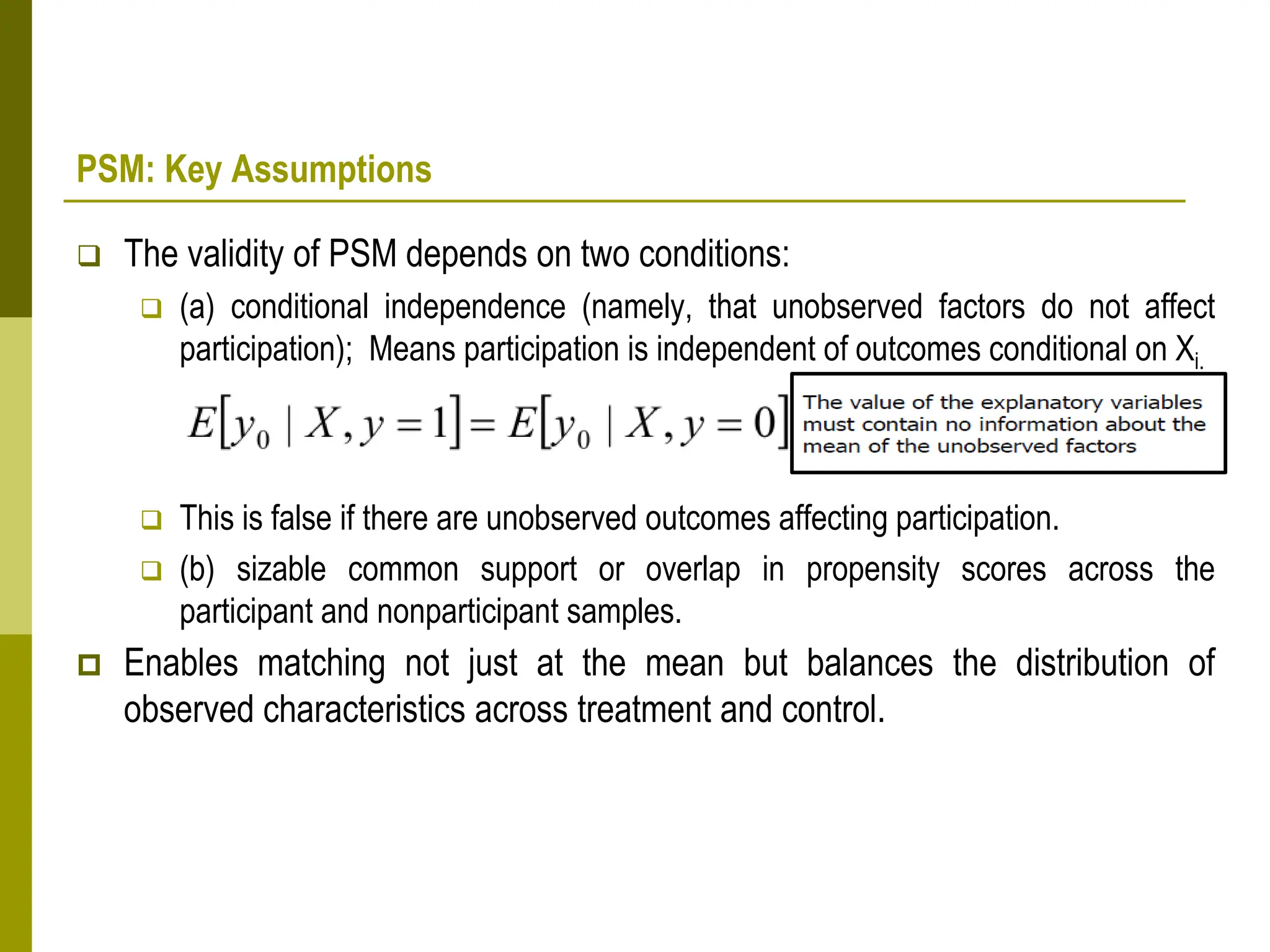

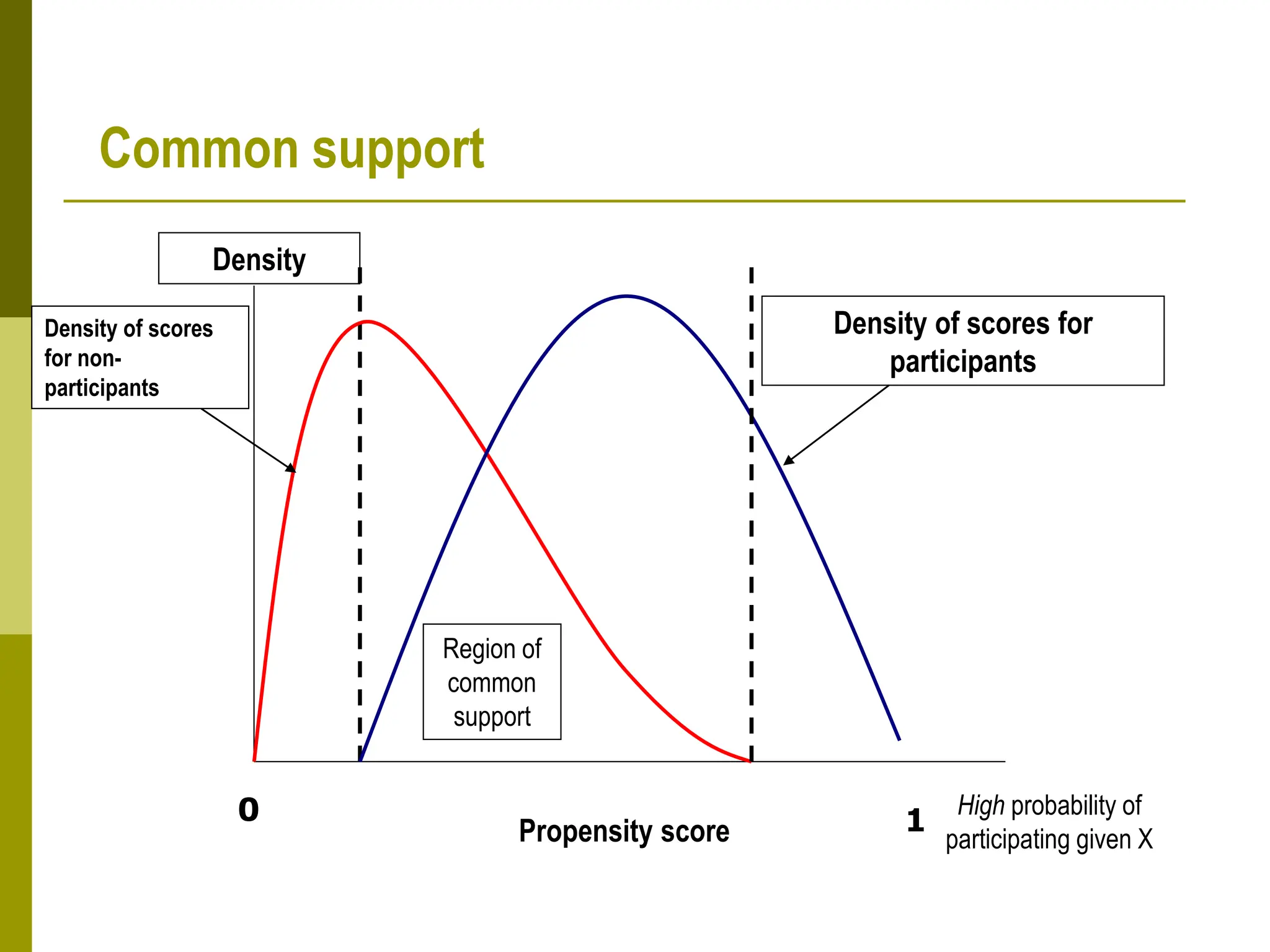

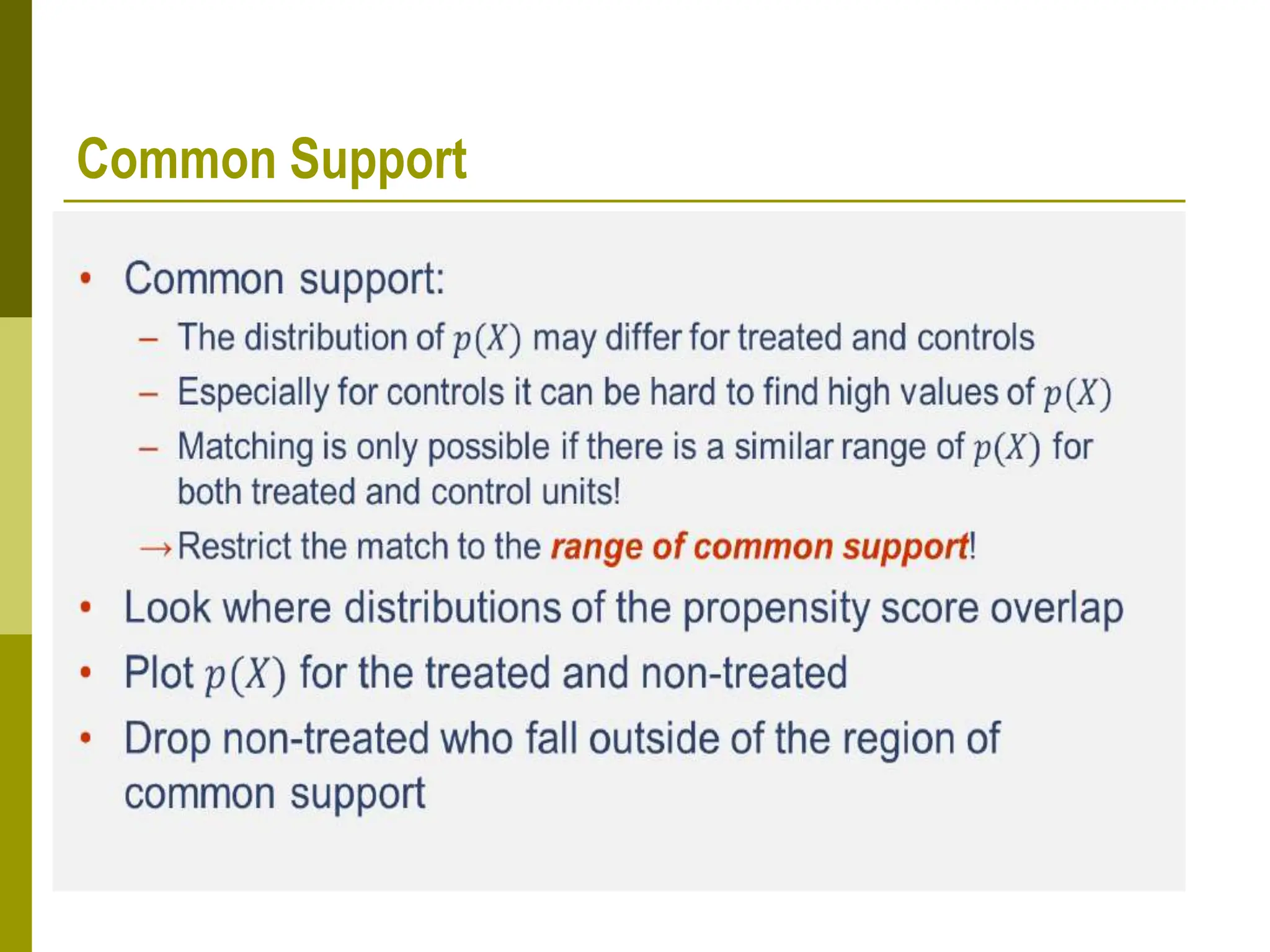

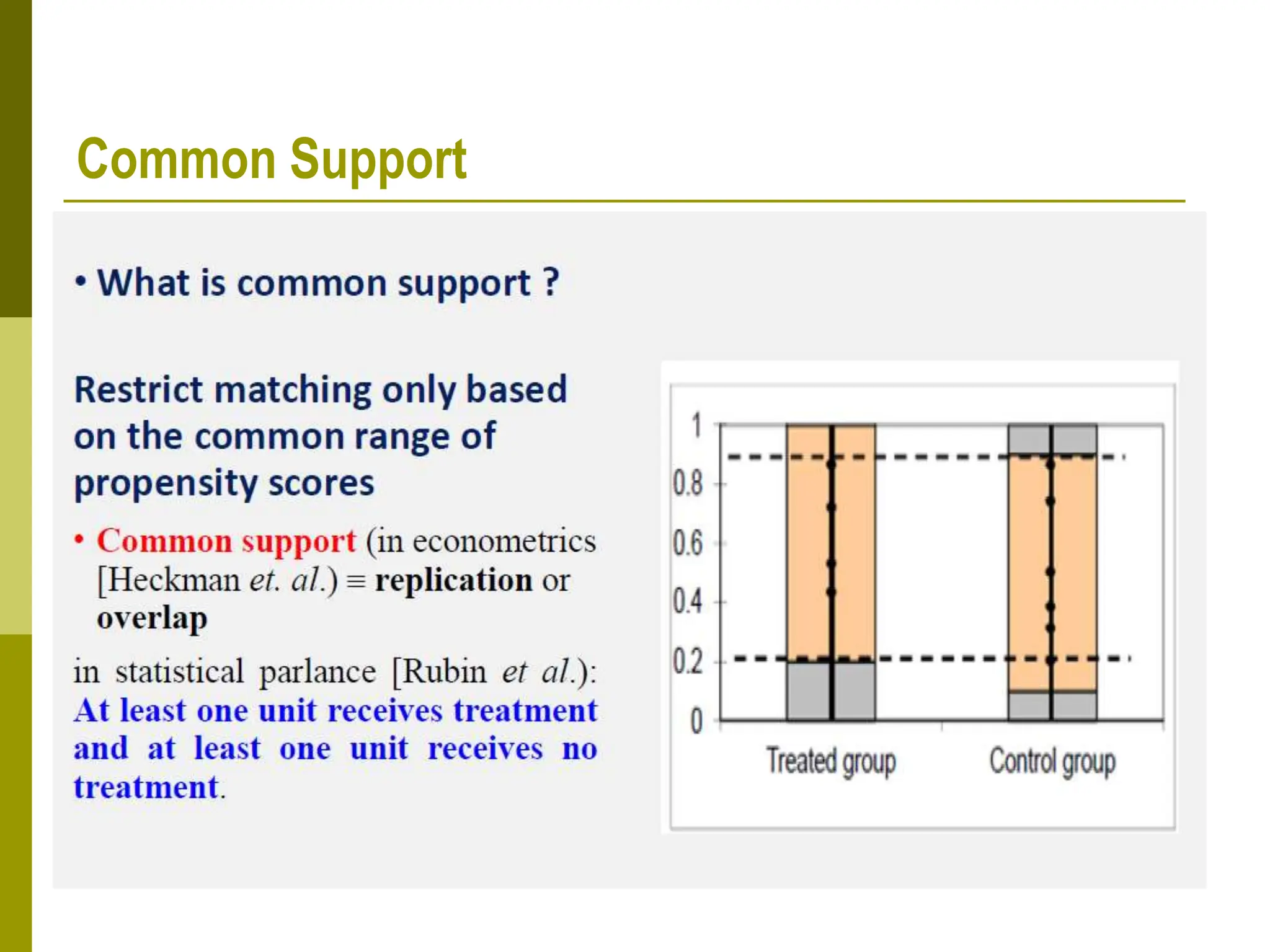

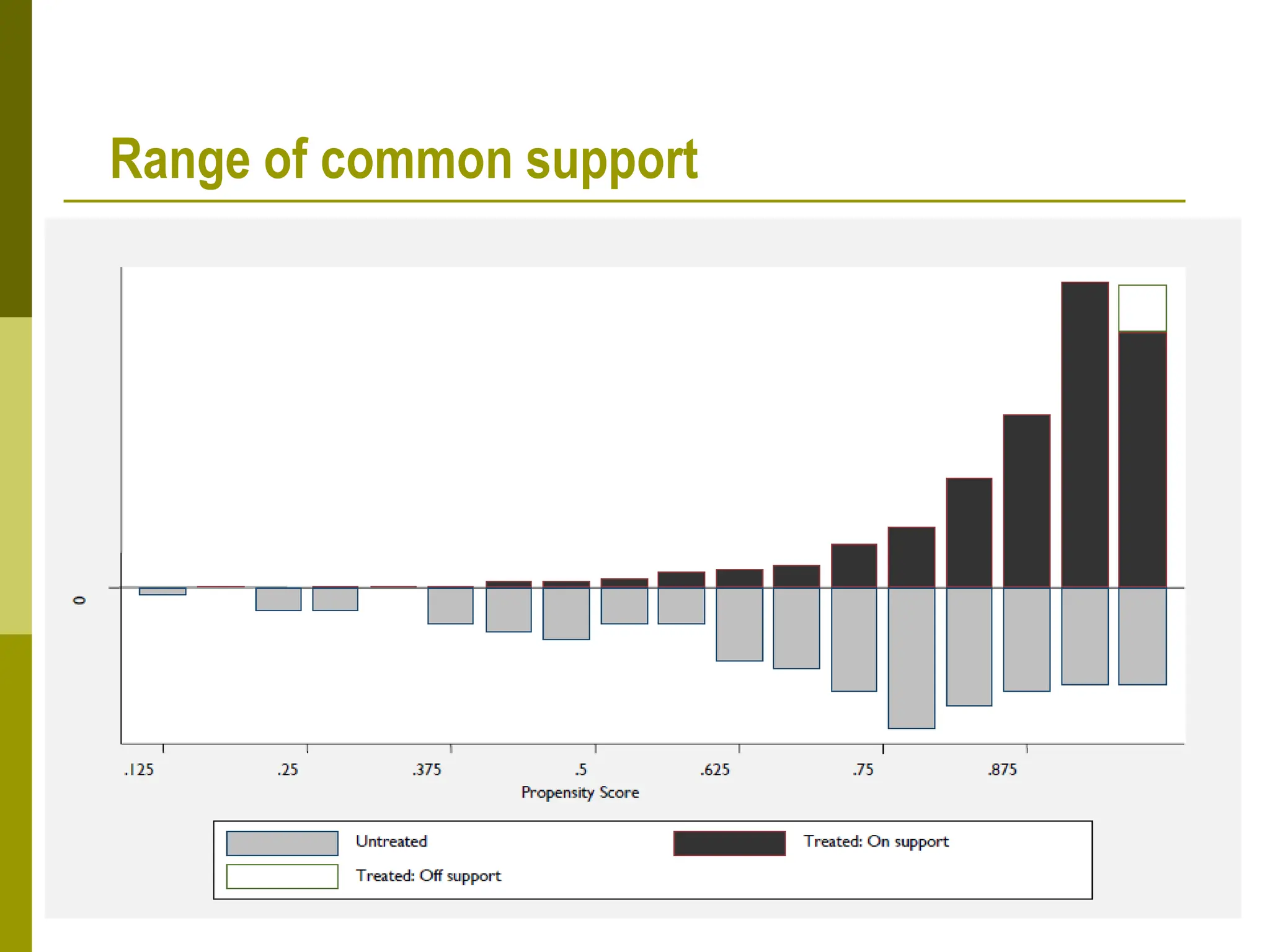

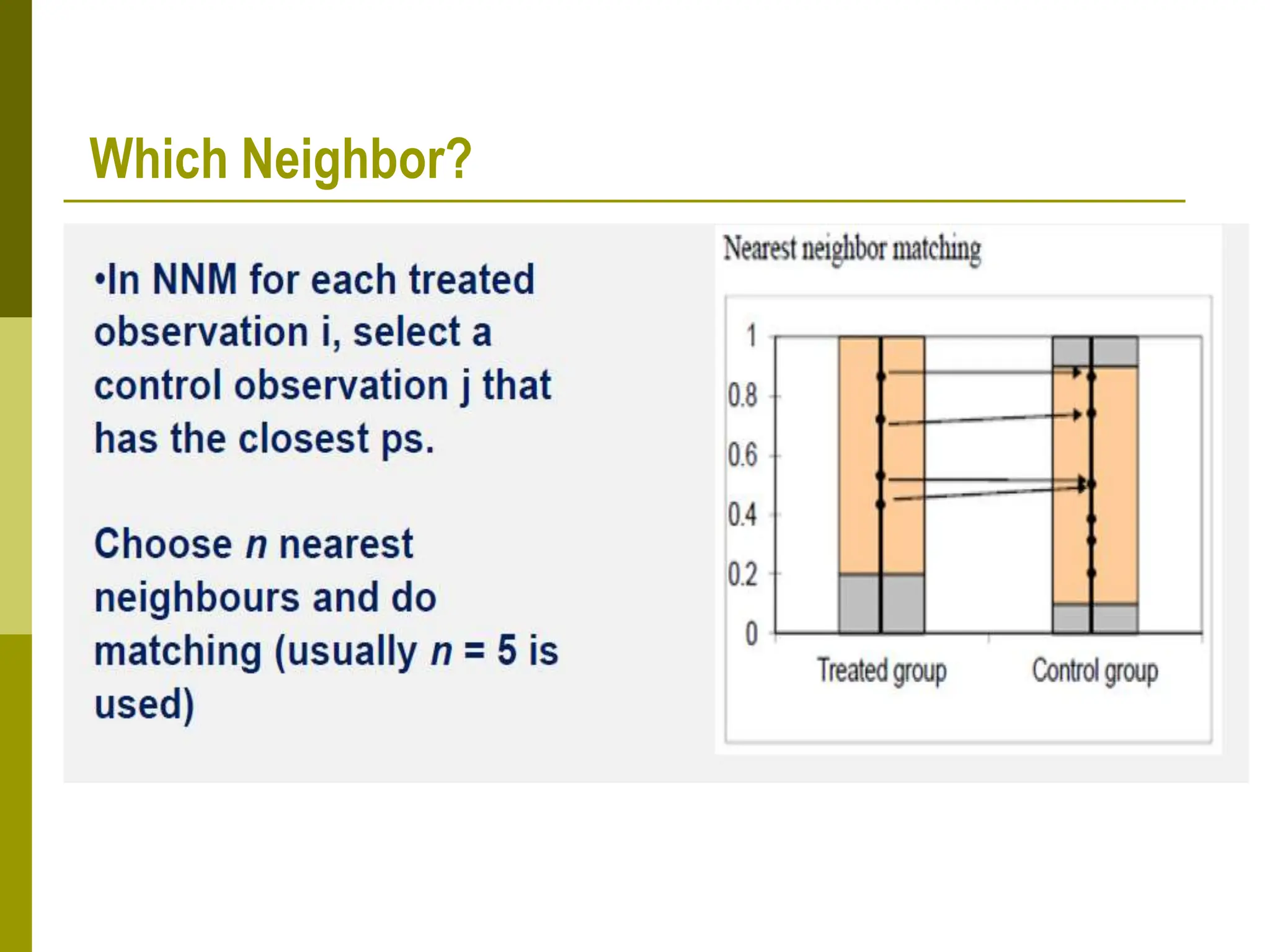

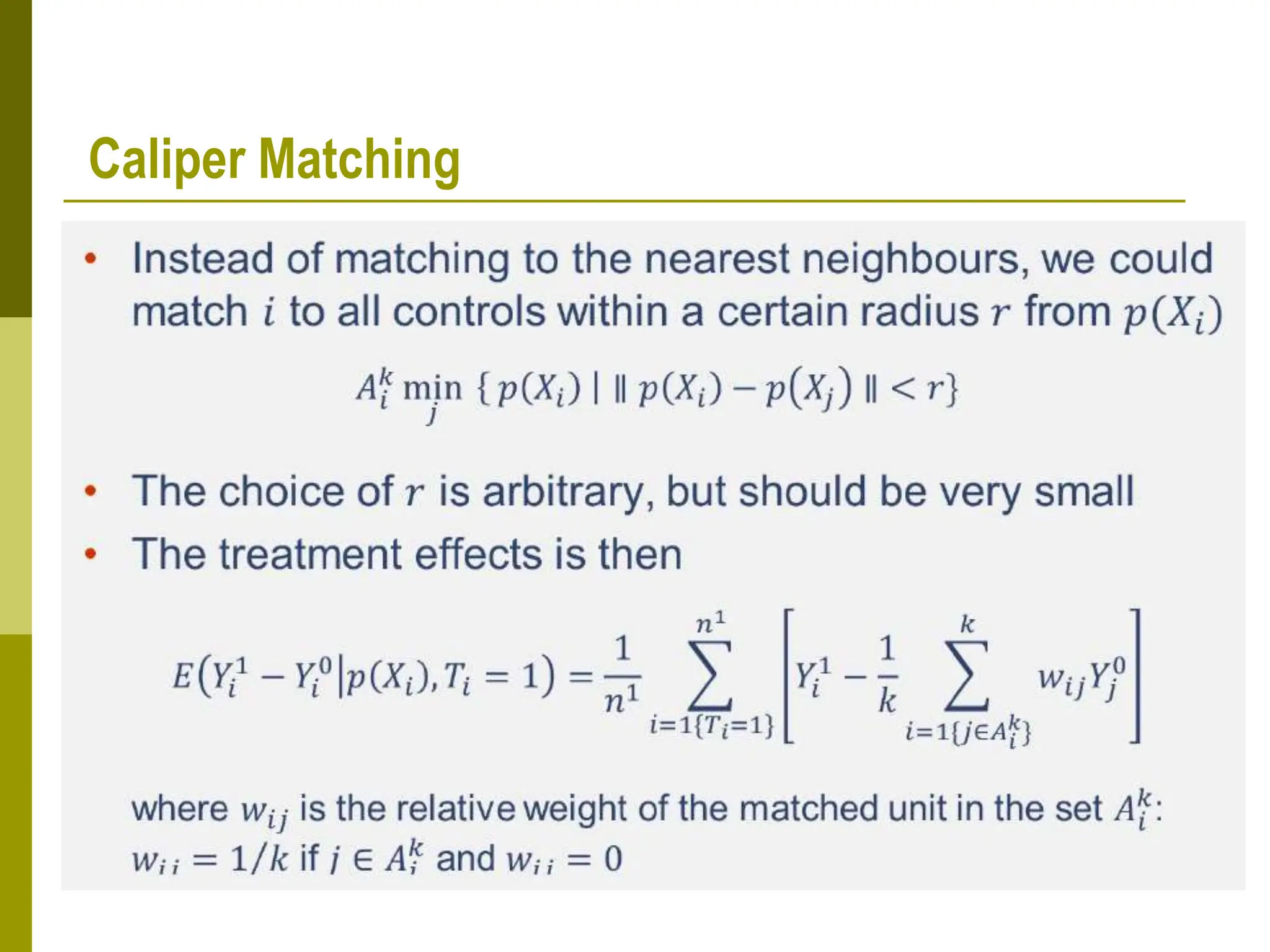

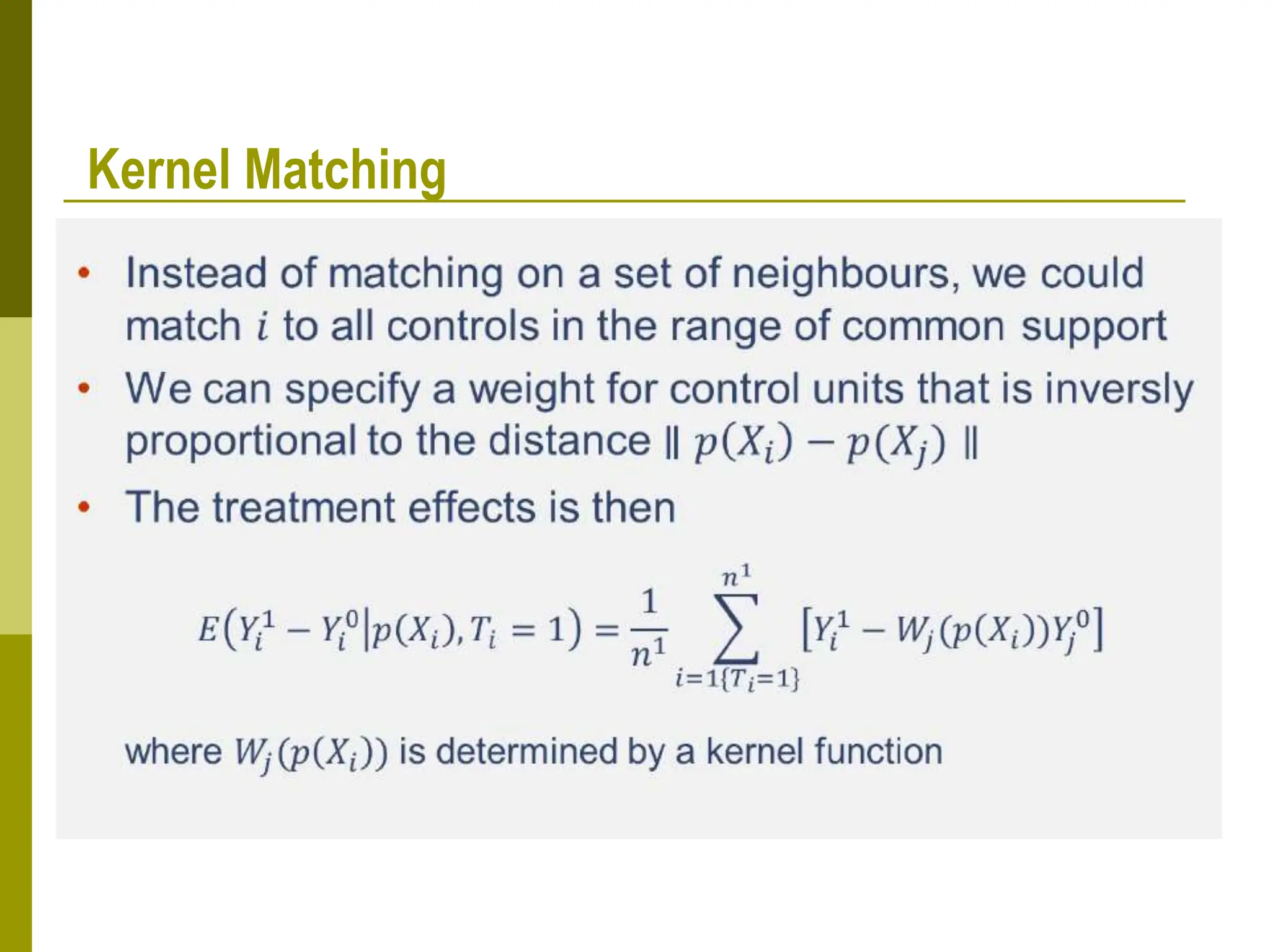

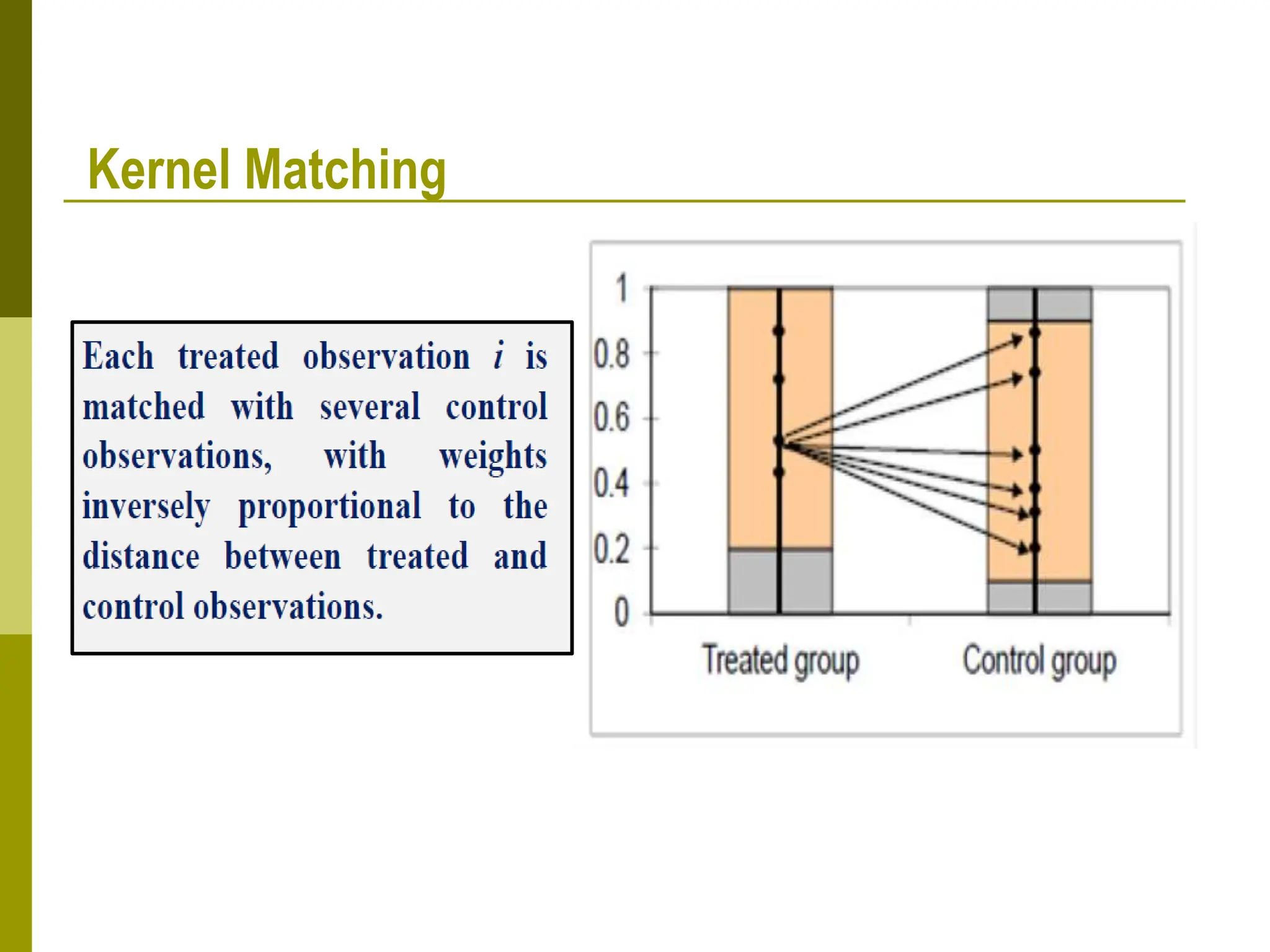

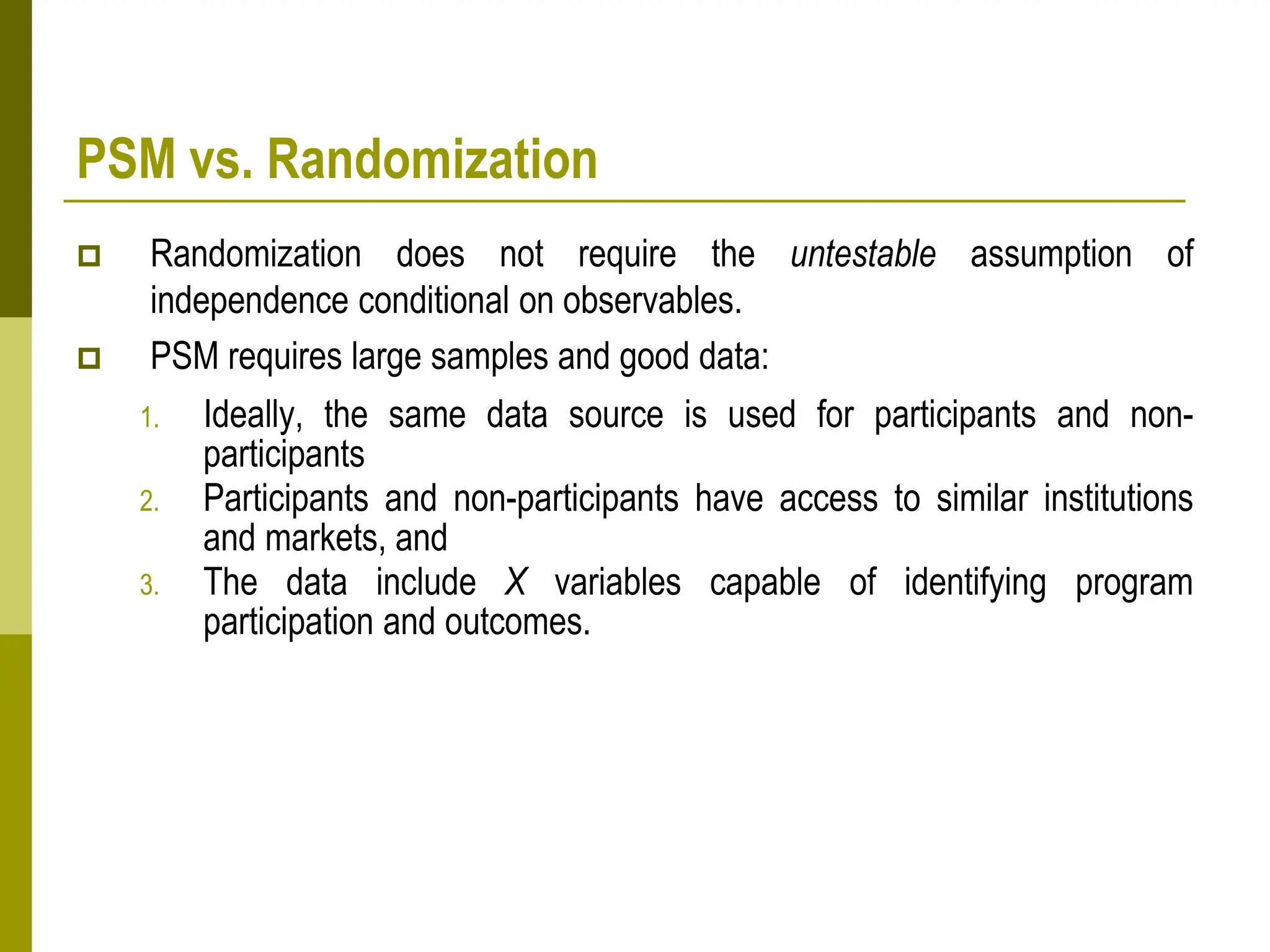

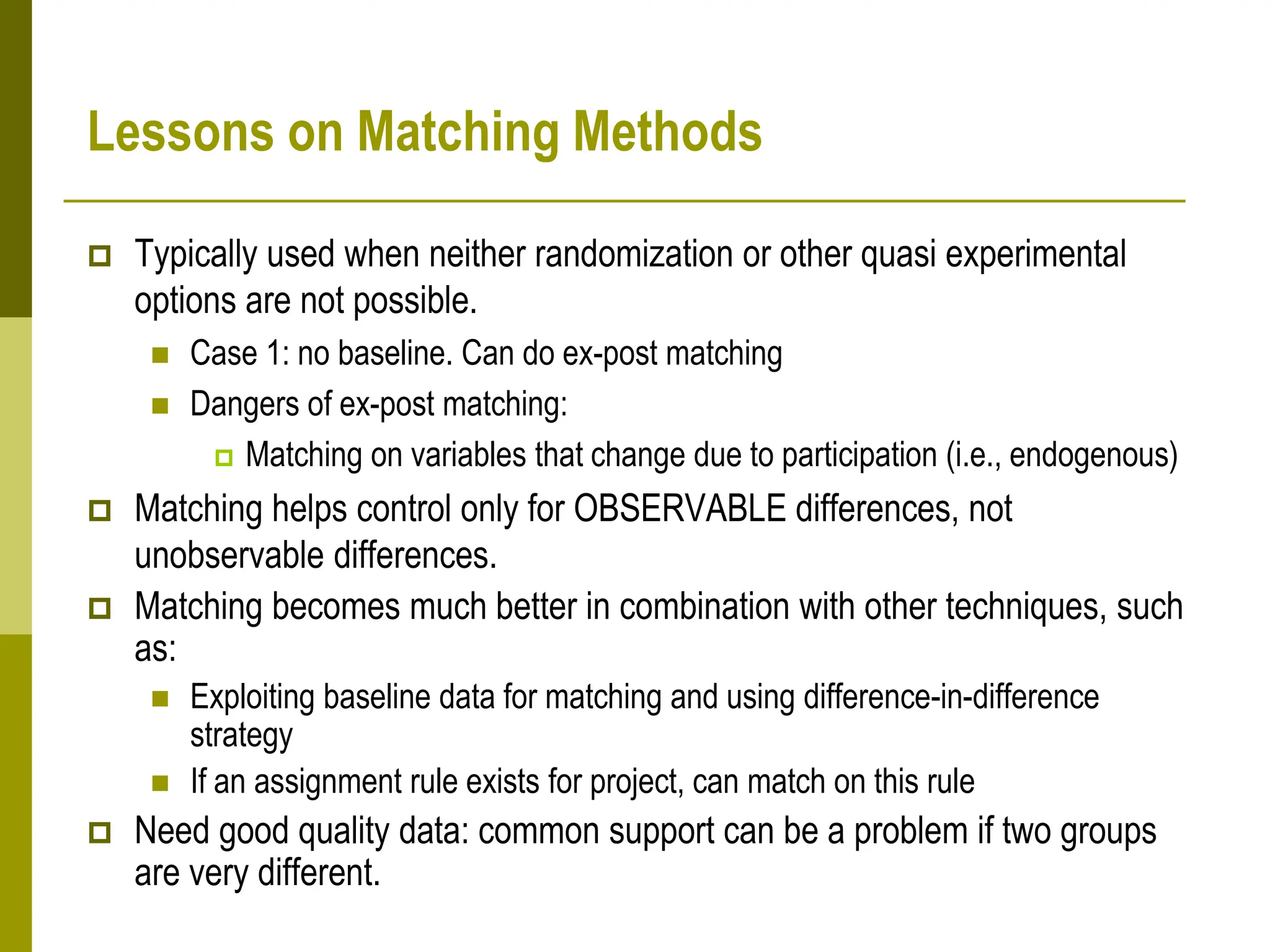

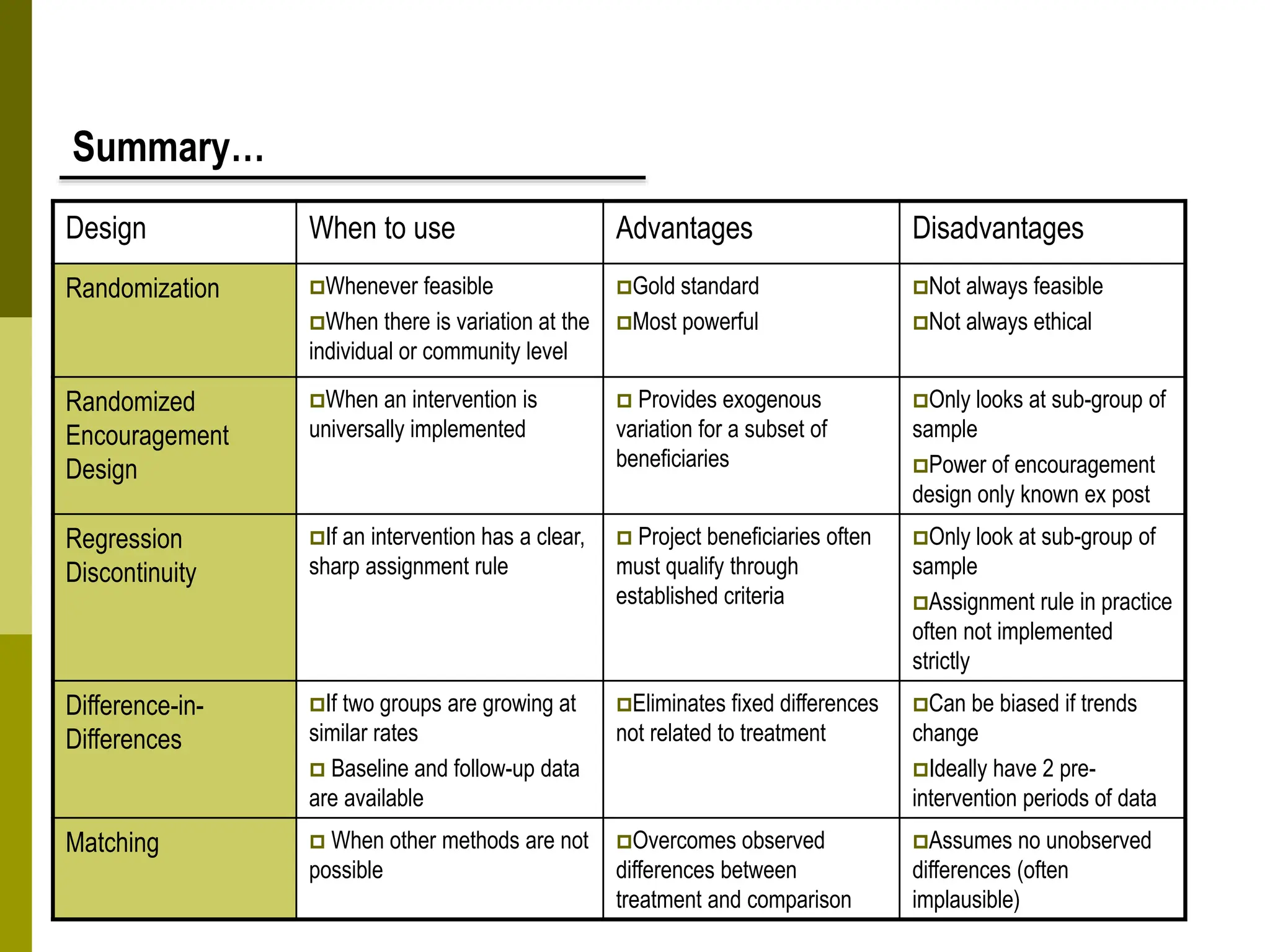

Propensity score matching (PSM) is a statistical technique used to estimate causal treatment effects. It constructs a comparison group that is matched to the treated group based on propensity scores, which represent the probability of participating in a treatment given observed characteristics. Key assumptions of PSM include conditional independence and common support. Different matching methods can then be used such as nearest neighbor matching, caliper matching, and kernel matching. PSM provides a way to control for selection bias and estimate treatment effects when a randomized experiment is not possible. However, it relies on the untestable assumption that selection depends only on observed characteristics.