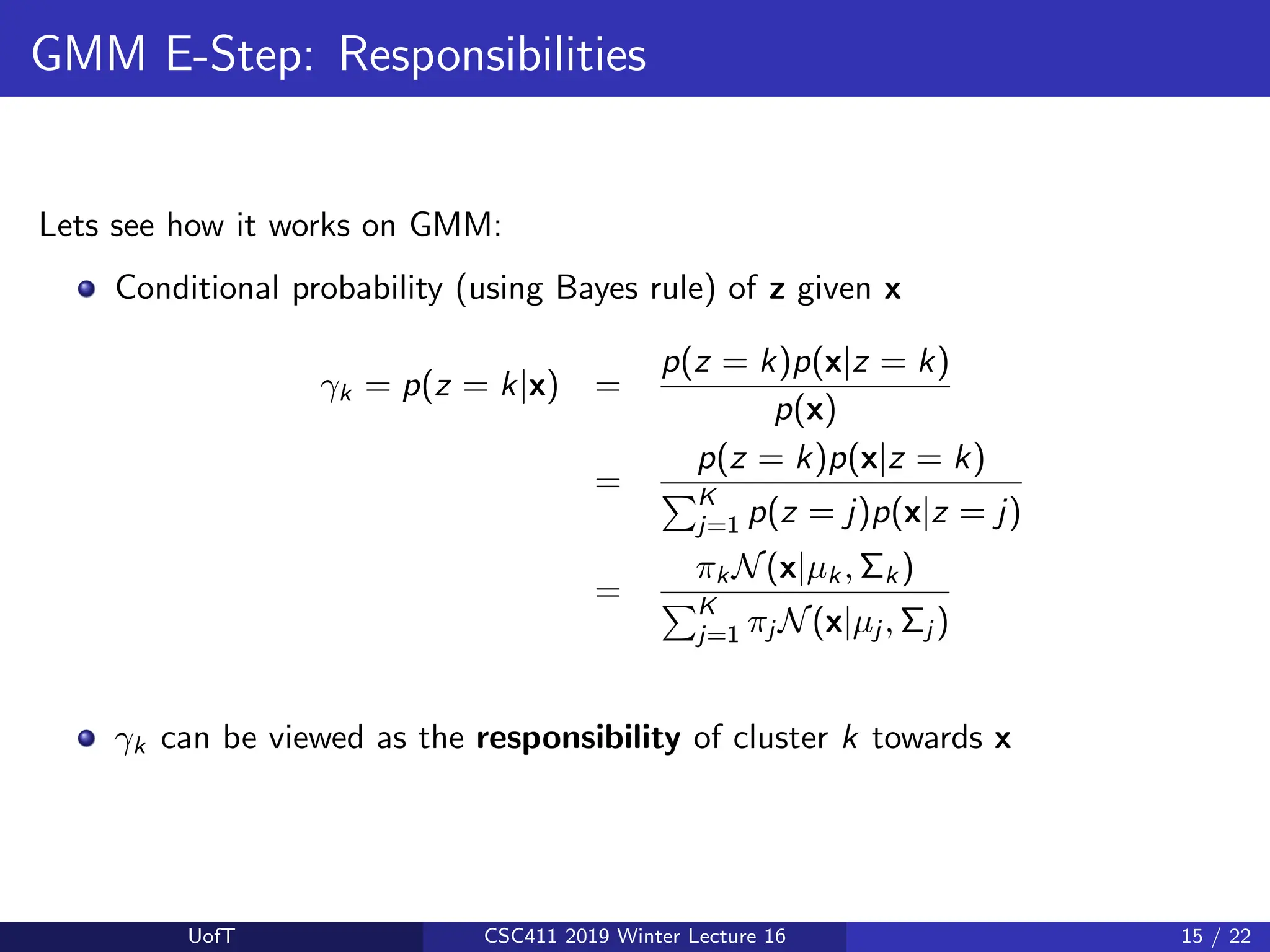

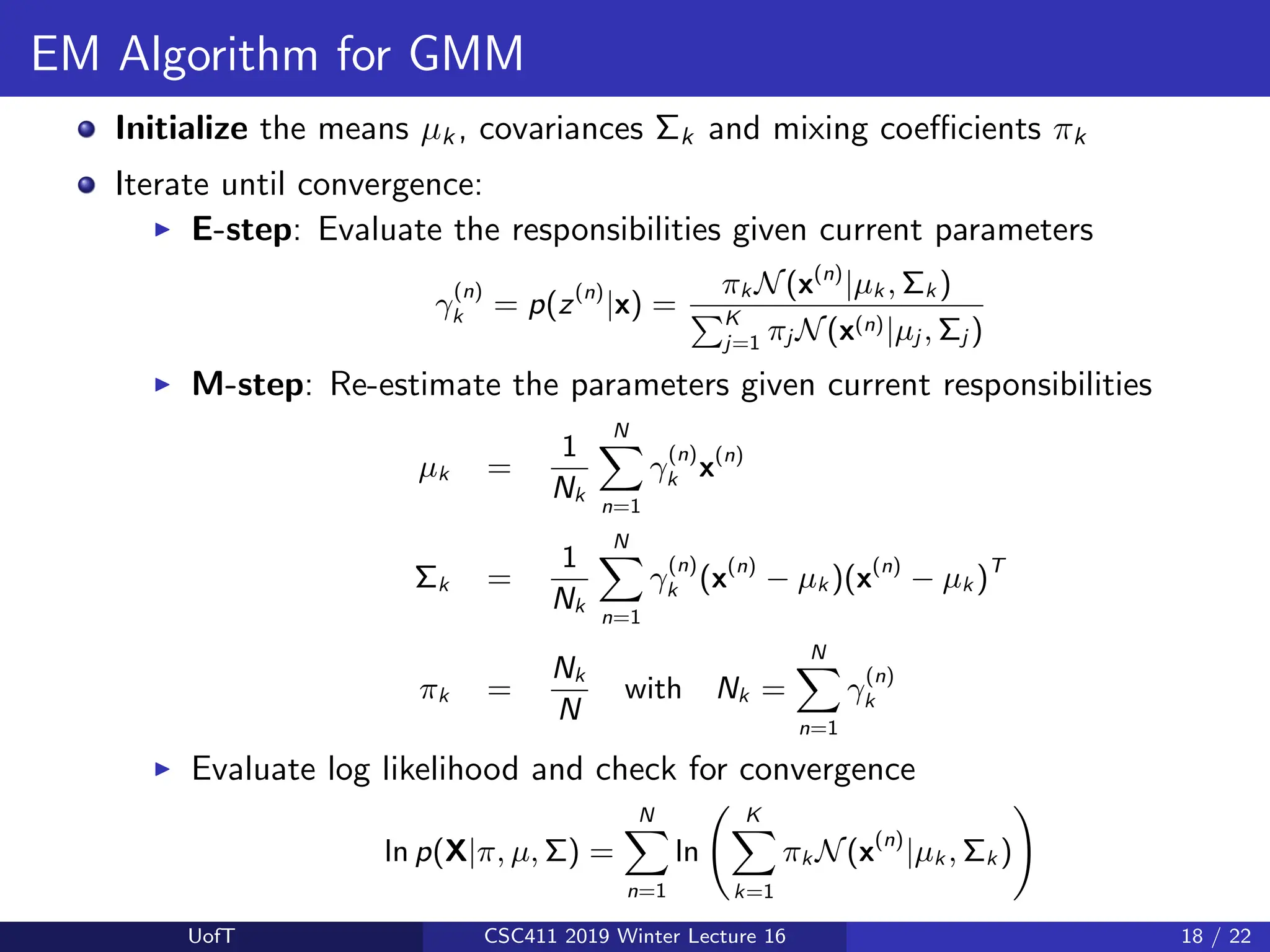

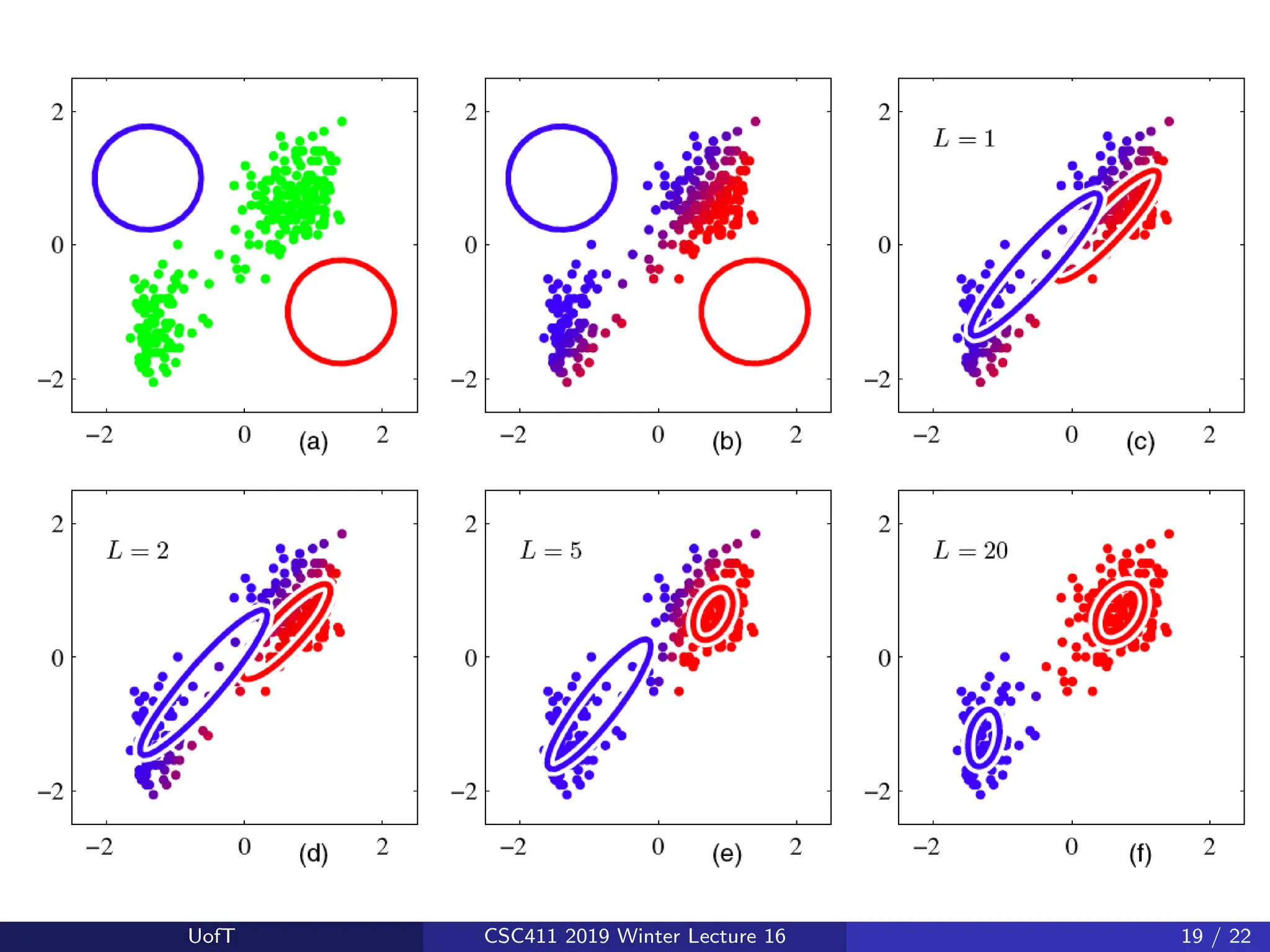

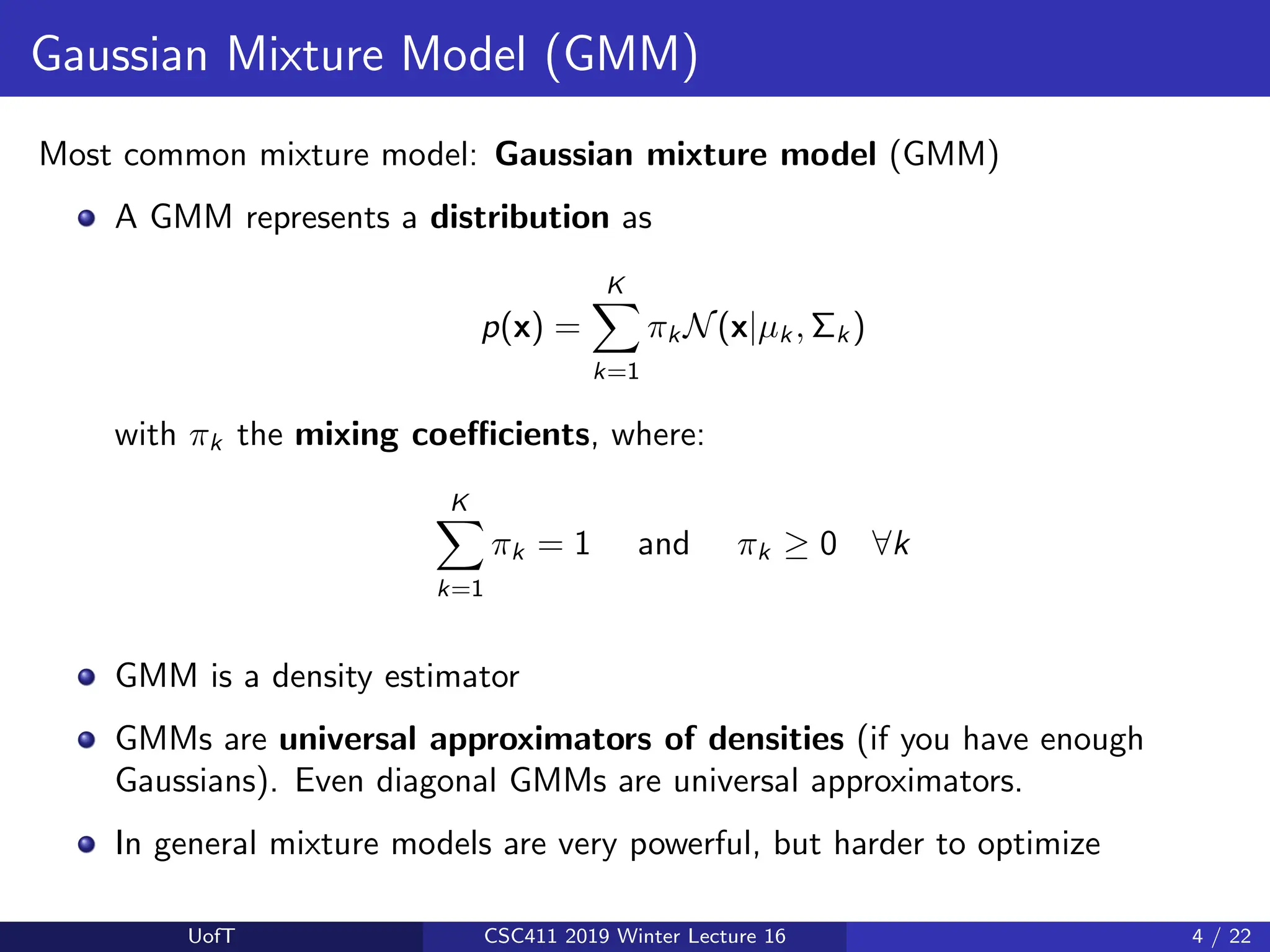

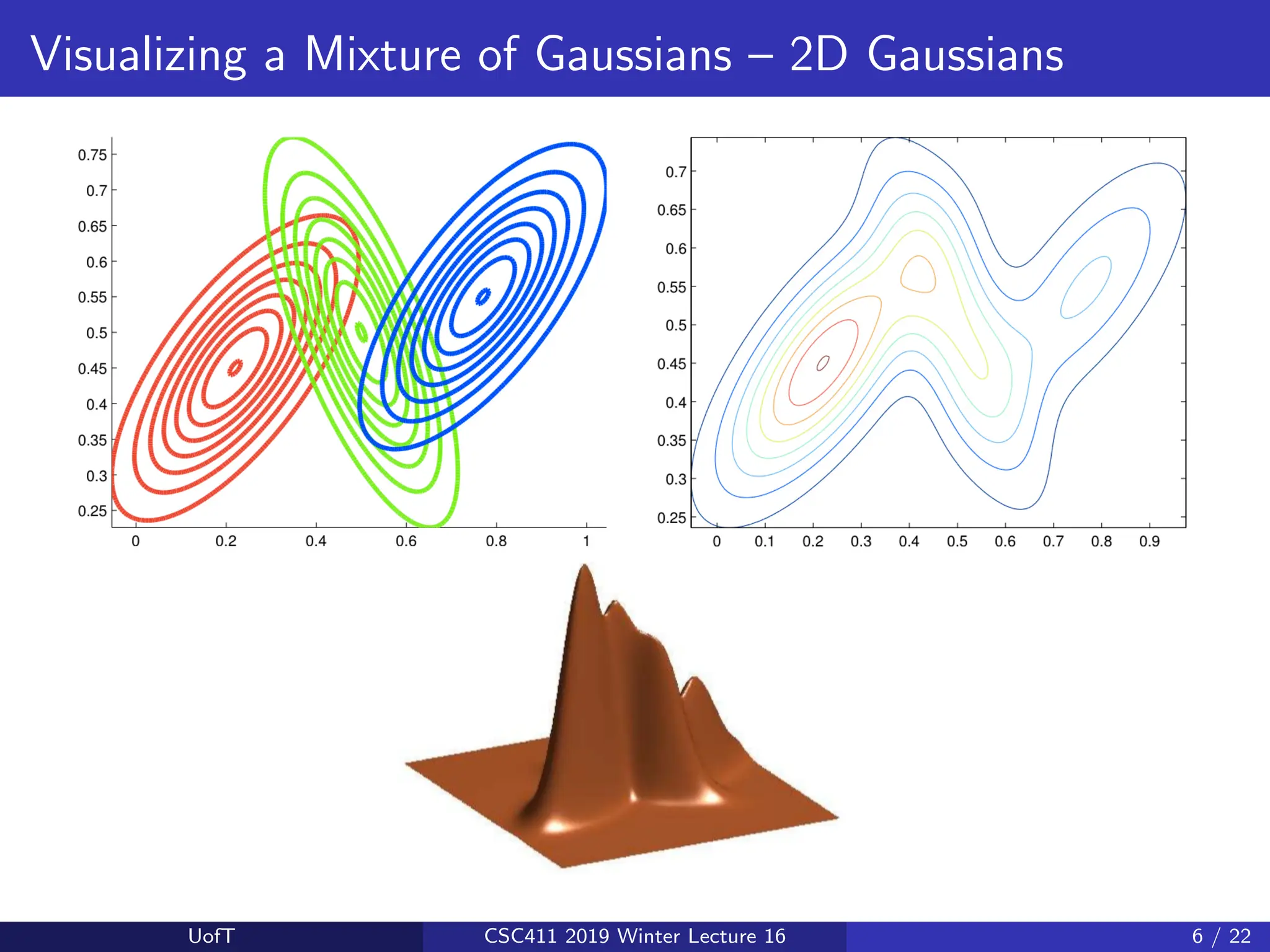

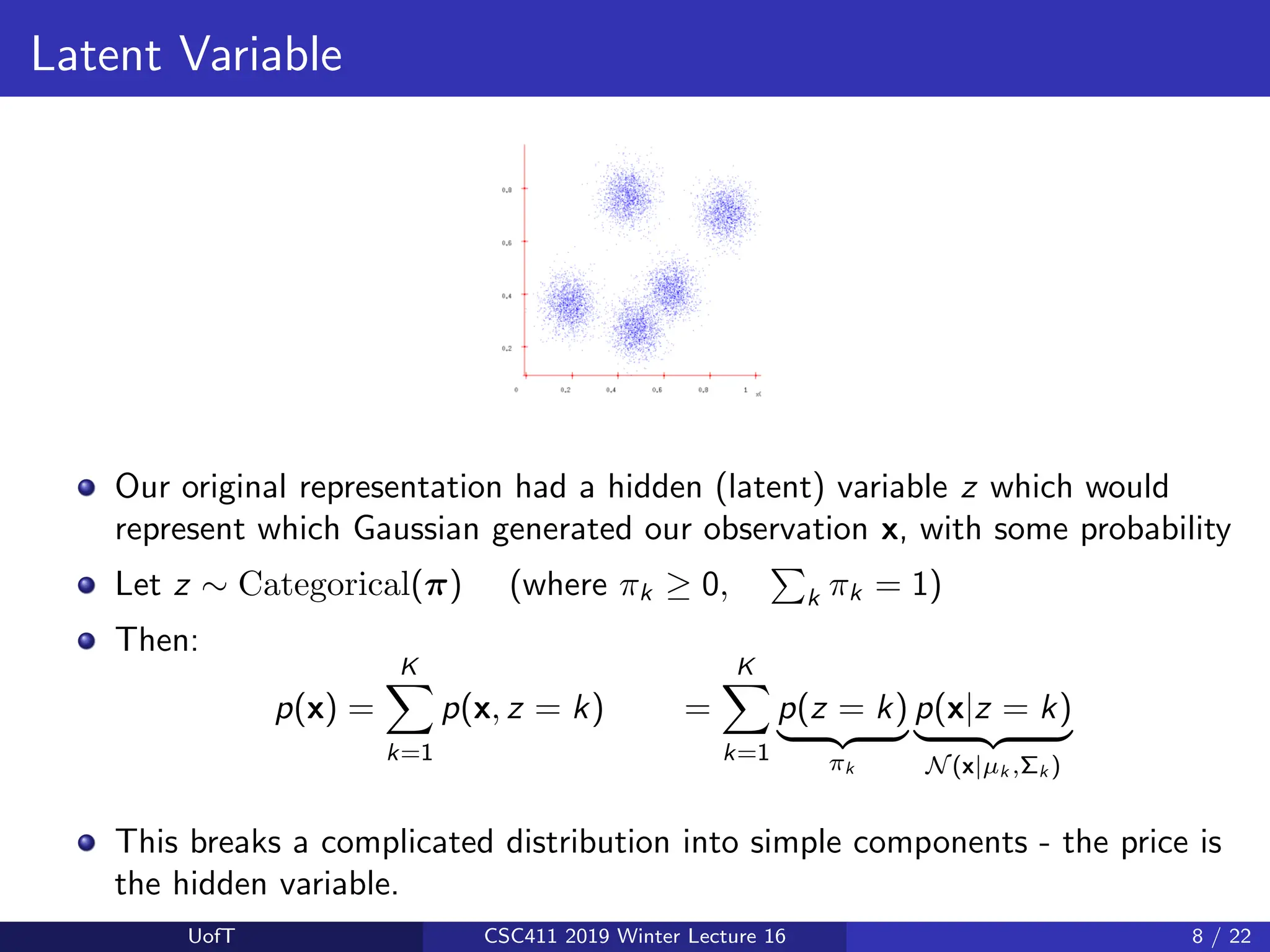

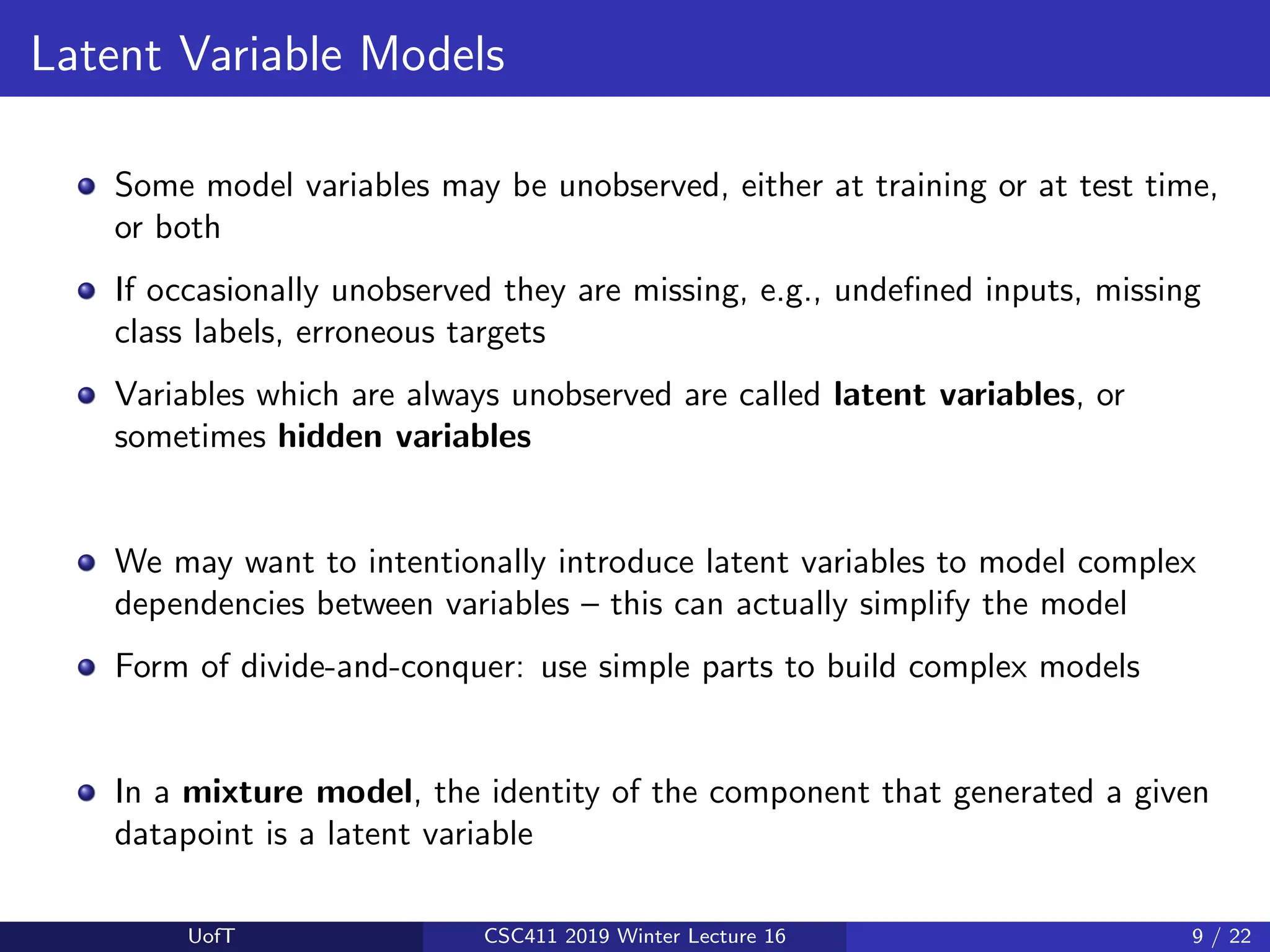

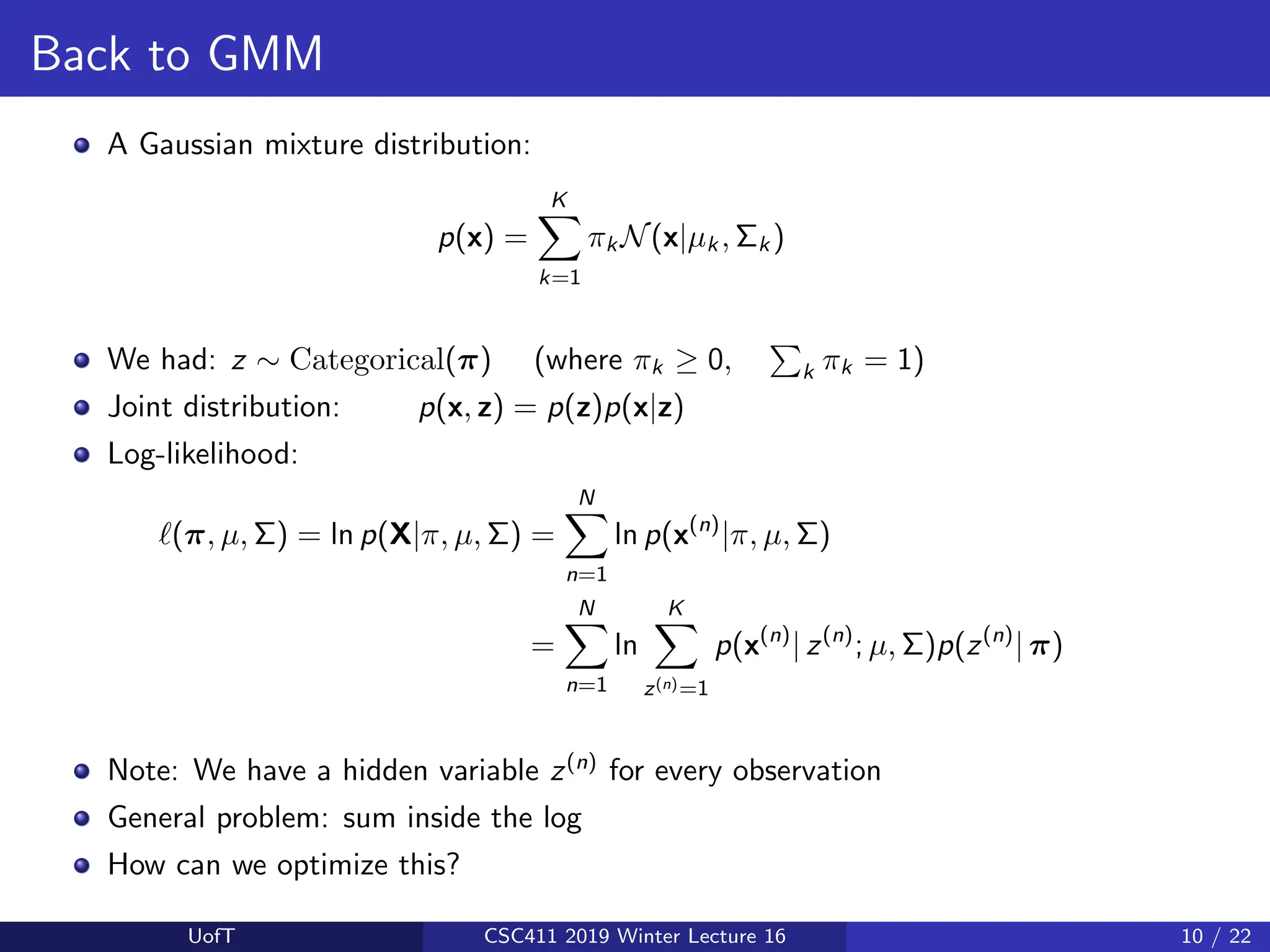

The lecture discusses Gaussian Mixture Models (GMMs) as a statistical method for unsupervised clustering, emphasizing the importance of modeling joint distributions without class labels. It outlines the Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm for optimizing GMMs, enabling the handling of latent variables during the clustering of data. GMMs offer a flexible and powerful approach to density estimation, distinguishing it from traditional methods like k-means by using soft assignments instead of hard class assignments.

![Visualizing a Mixture of Gaussians – 1D Gaussians

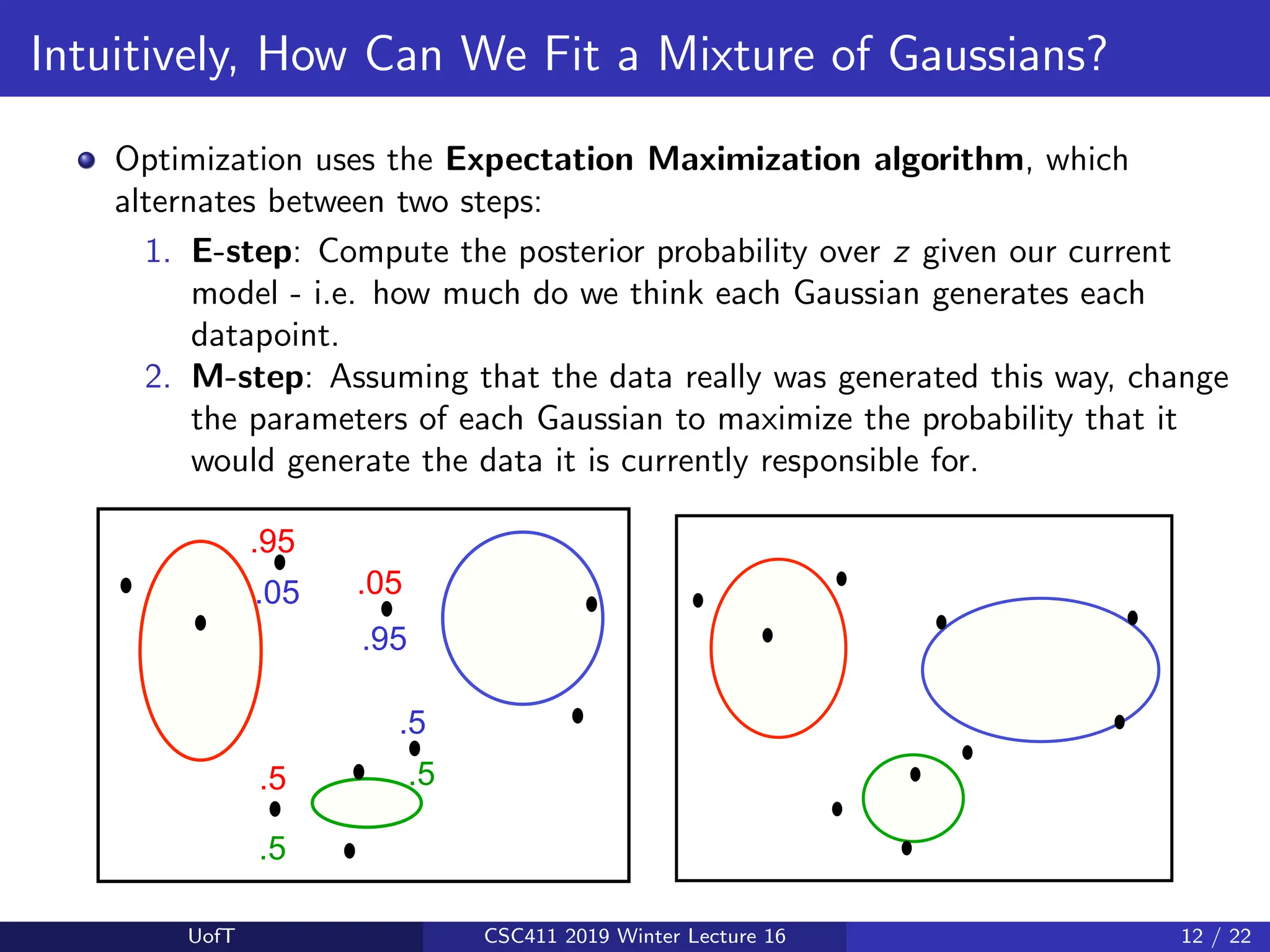

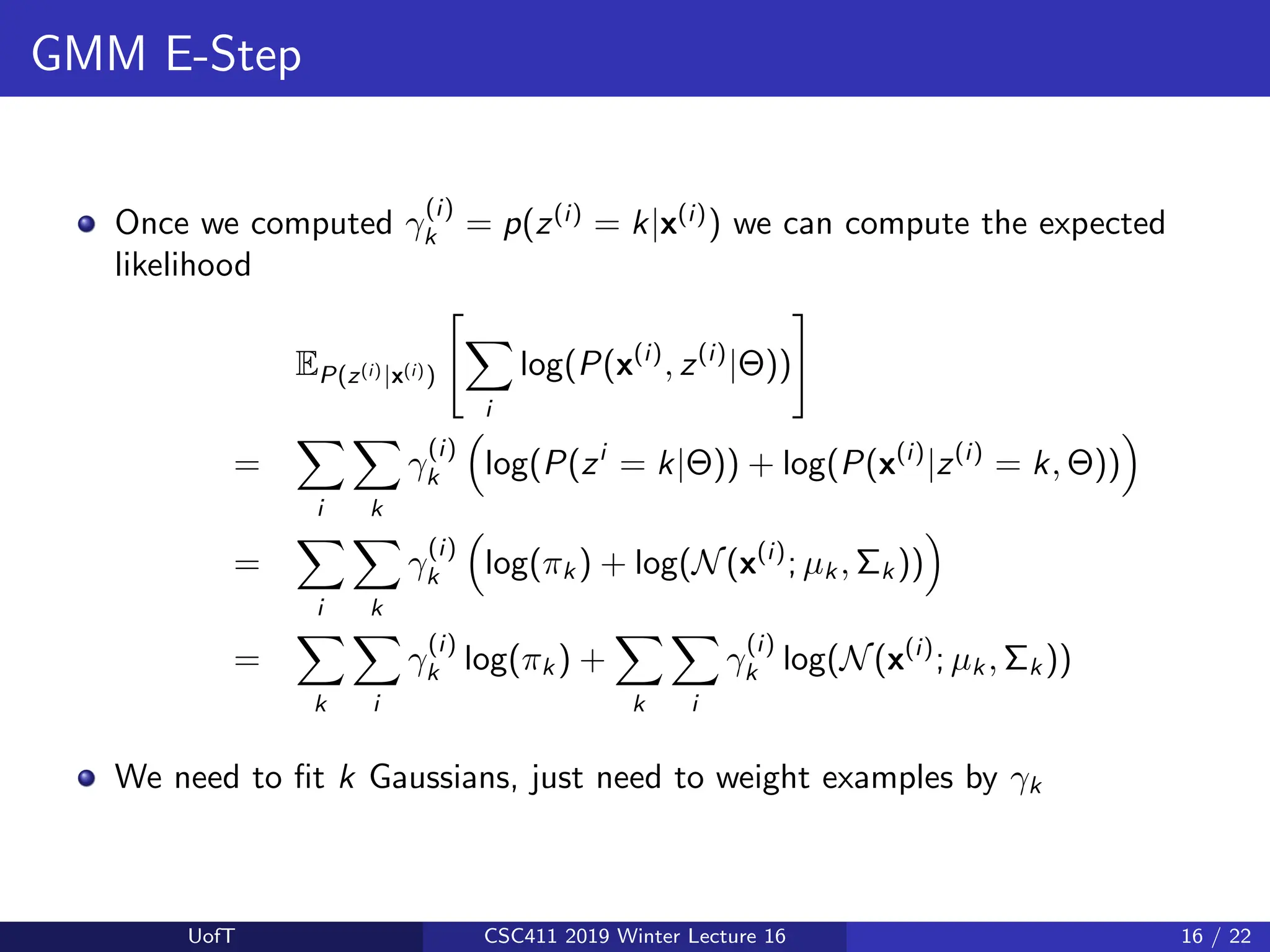

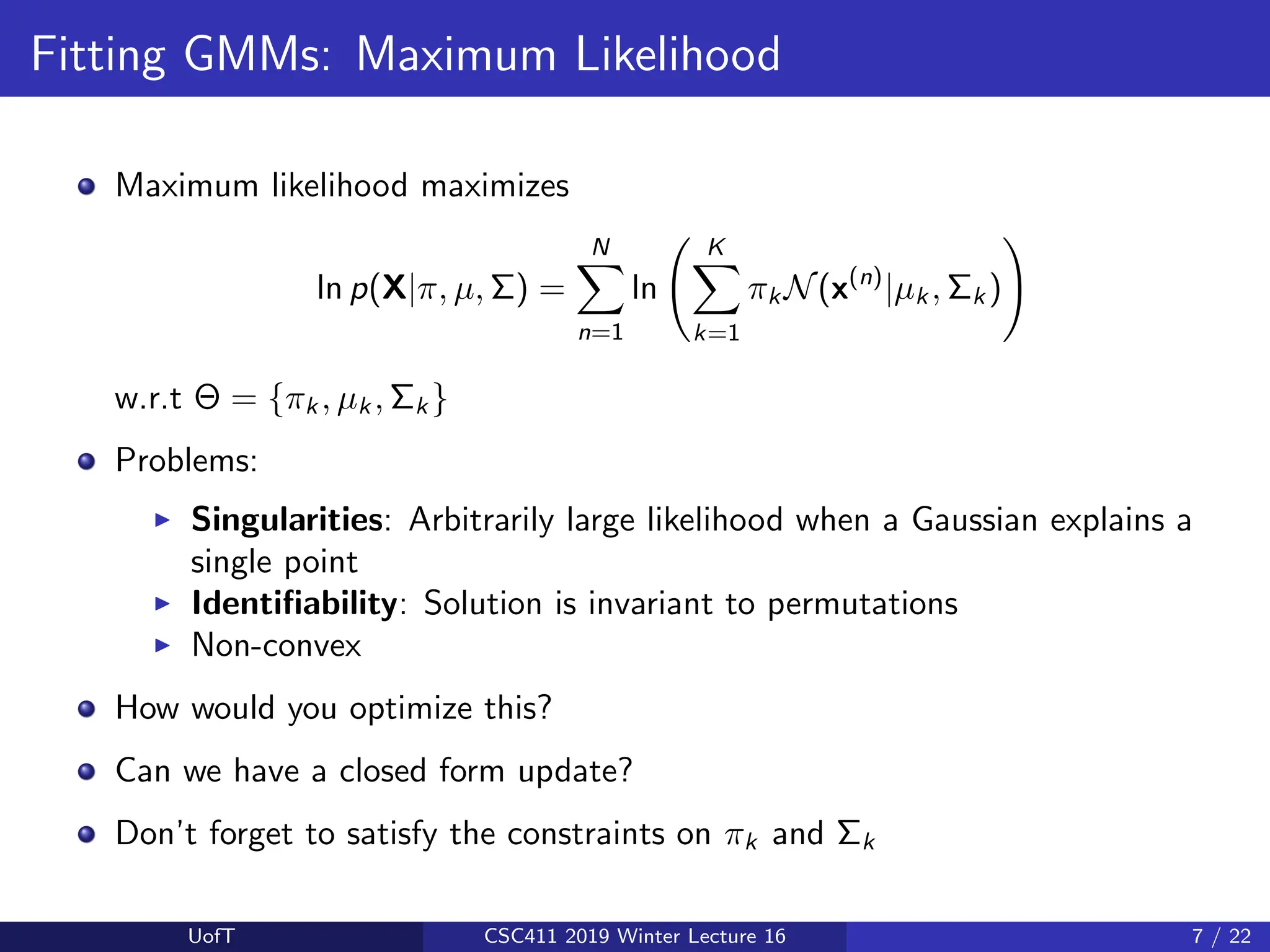

If you fit a Gaussian to data:

Now, we are trying to fit a GMM (with K = 2 in this example):

[Slide credit: K. Kutulakos]

UofT CSC411 2019 Winter Lecture 16 5 / 22](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lec16-240730043658-16282070/75/Machine-learning-supervised-learning-j-5-2048.jpg)

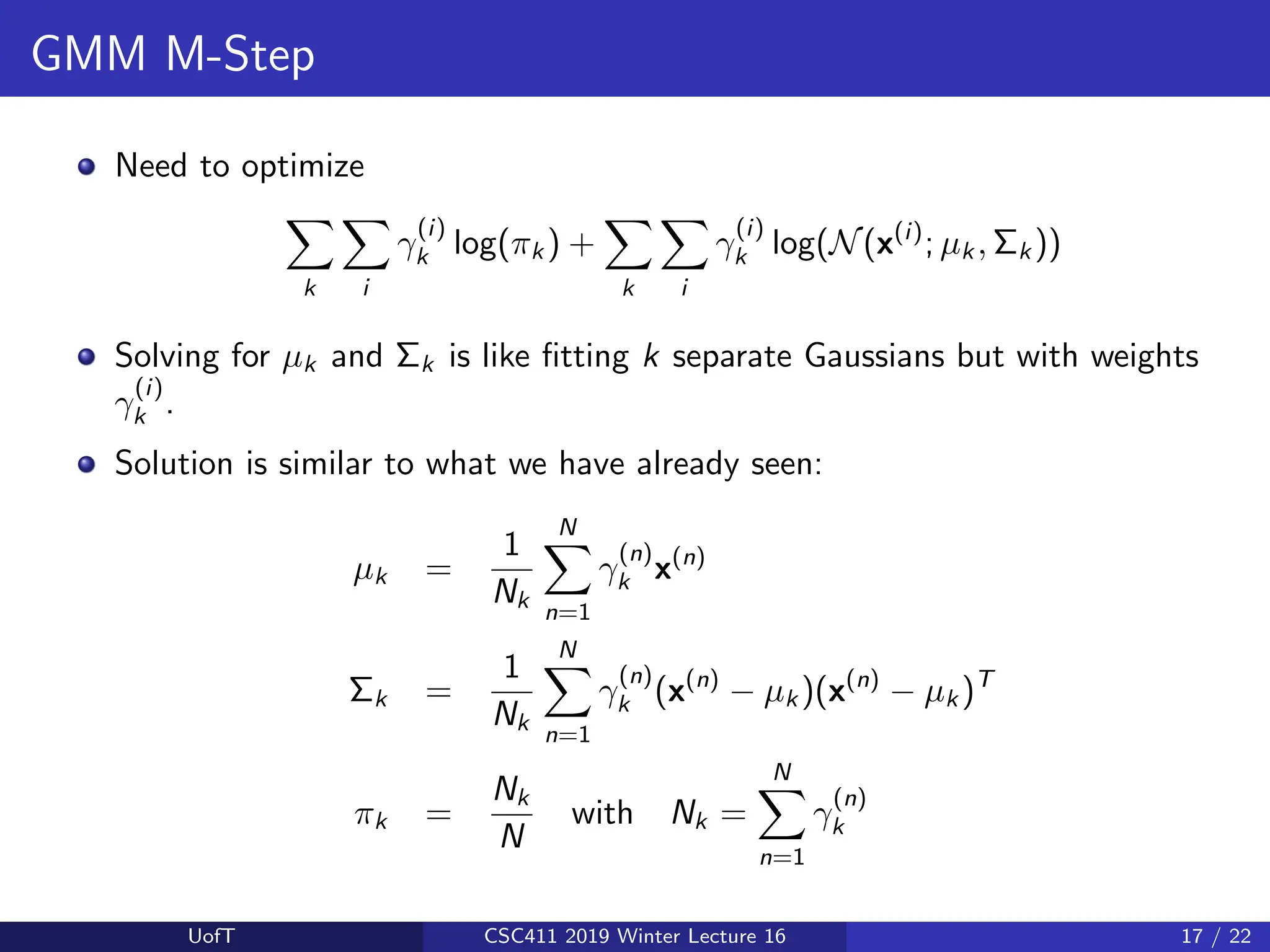

![Maximum Likelihood

If we knew z(n)

for every x(n)

, the maximum likelihood problem is easy:

`(π, µ, Σ) =

N

X

n=1

ln p(x(n)

, z(n)

|π, µ, Σ) =

N

X

n=1

ln p(x(n)

| z(n)

; µ, Σ)+ln p(z(n)

| π)

We have been optimizing something similar for Gaussian bayes classifiers

We would get this:

µk =

PN

n=1 1[z(n)=k] x(n)

PN

n=1 1[z(n)=k]

Σk =

PN

n=1 1[z(n)=k] (x(n)

− µk )(x(n)

− µk )T

PN

n=1 1[z(n)=k]

πk =

1

N

N

X

n=1

1[z(n)=k]

UofT CSC411 2019 Winter Lecture 16 11 / 22](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lec16-240730043658-16282070/75/Machine-learning-supervised-learning-j-11-2048.jpg)