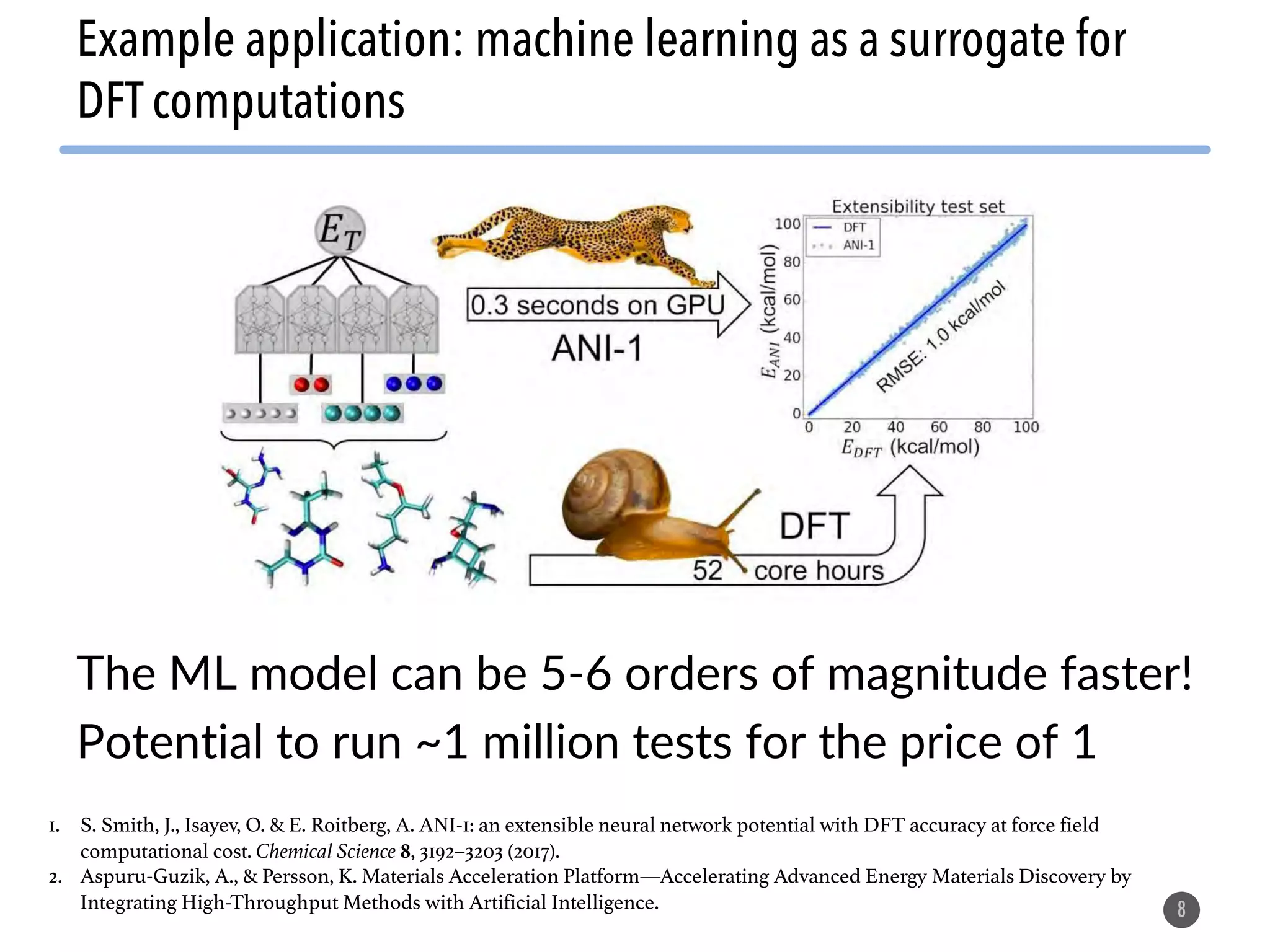

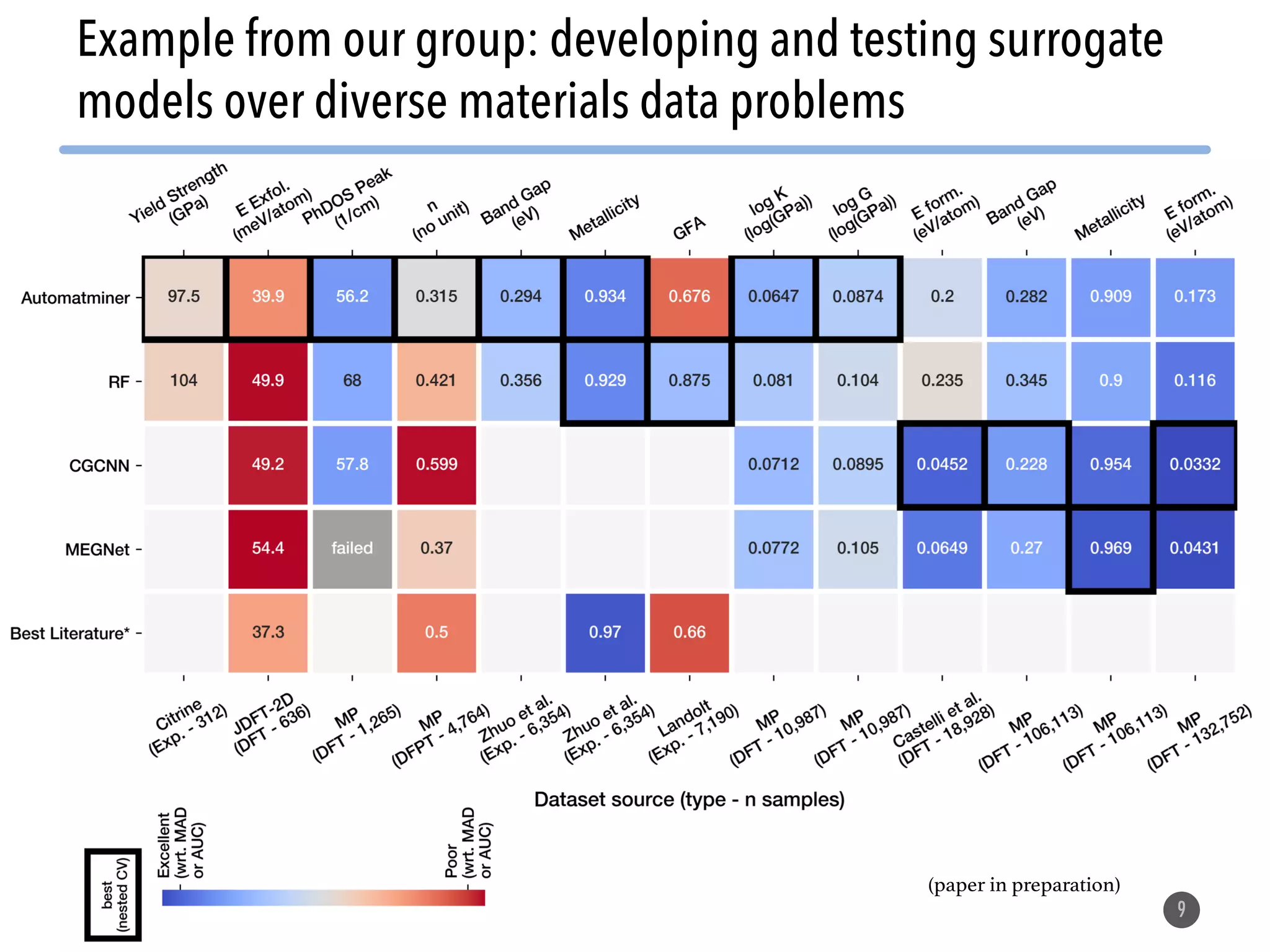

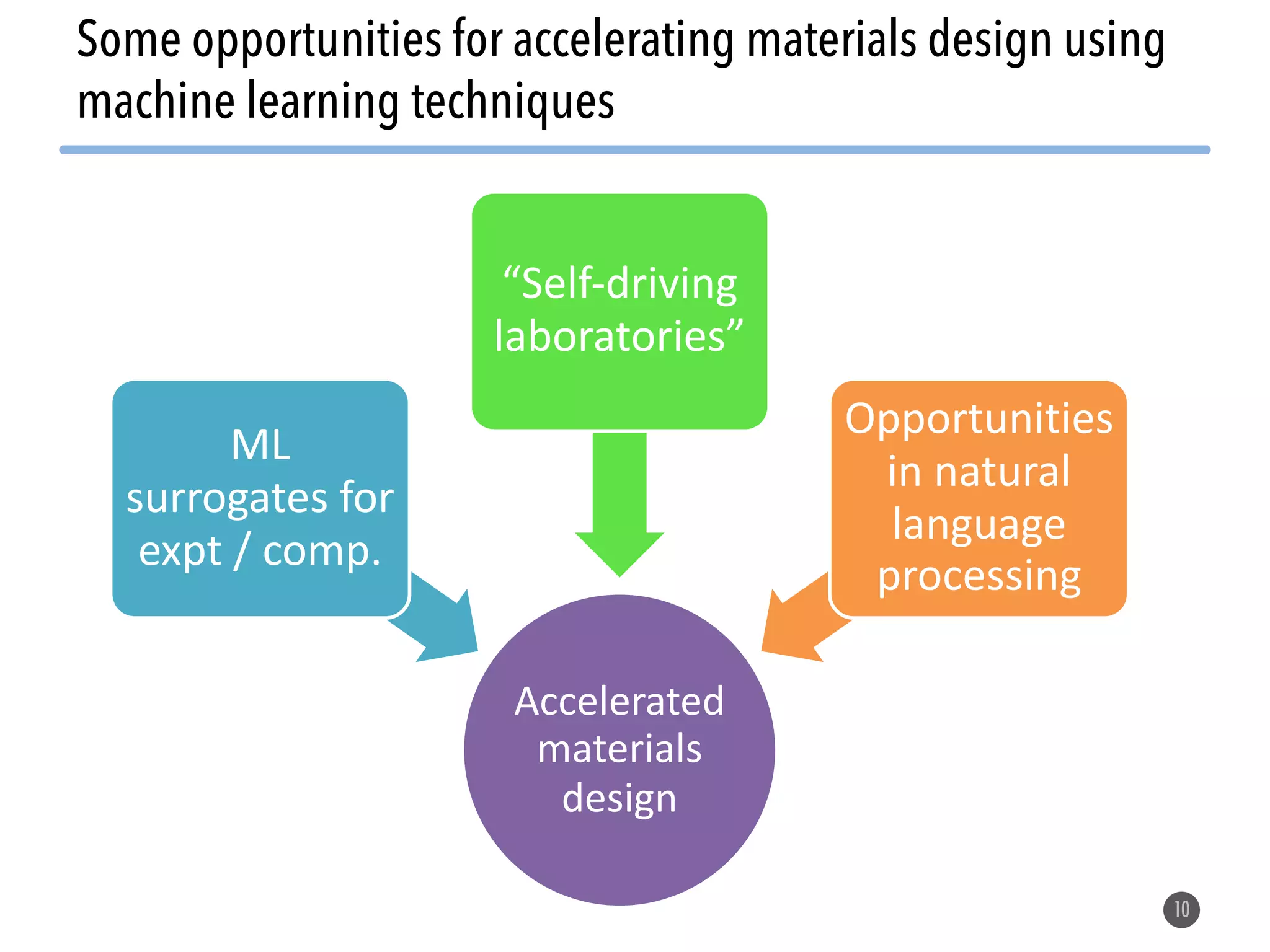

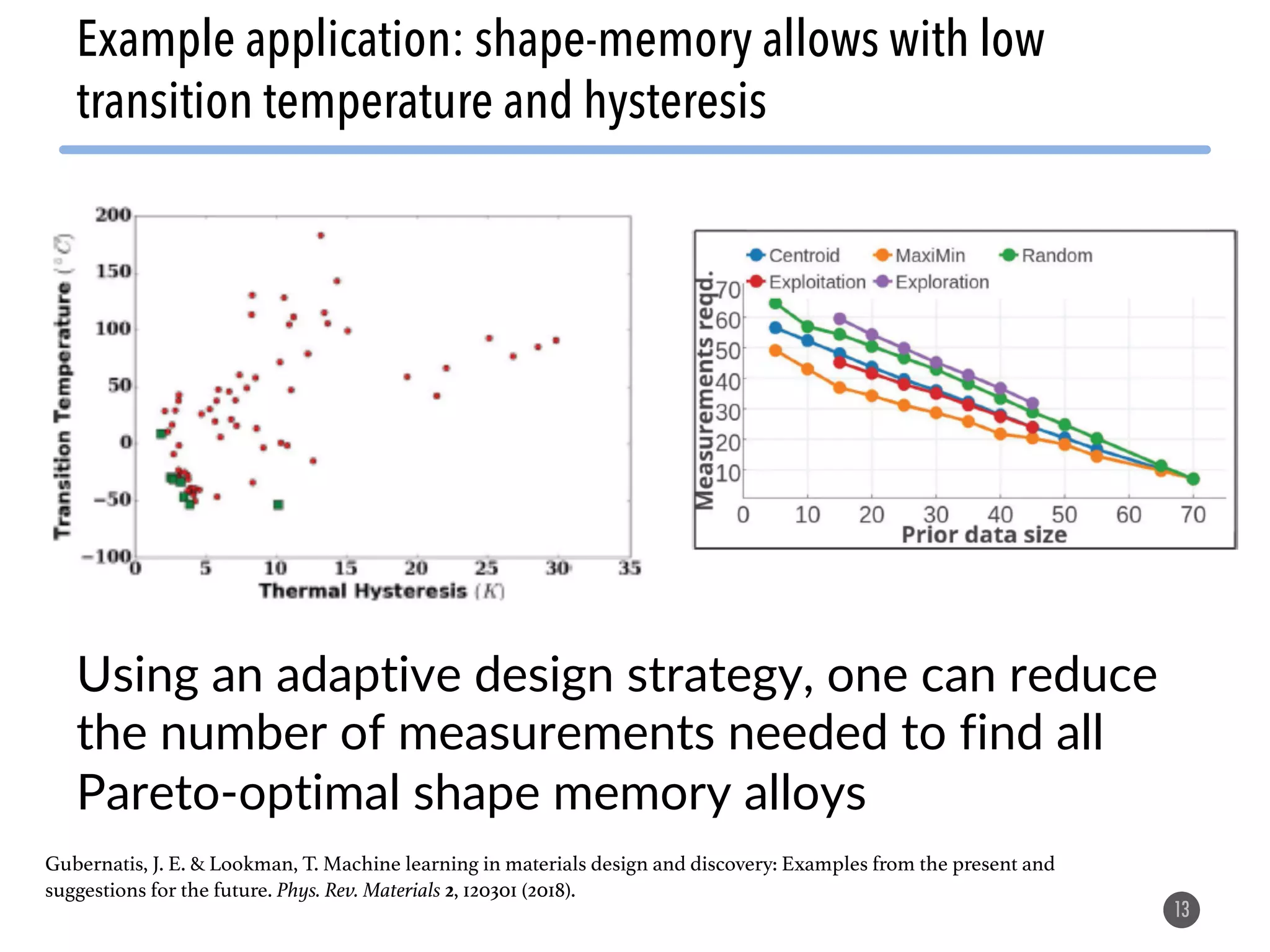

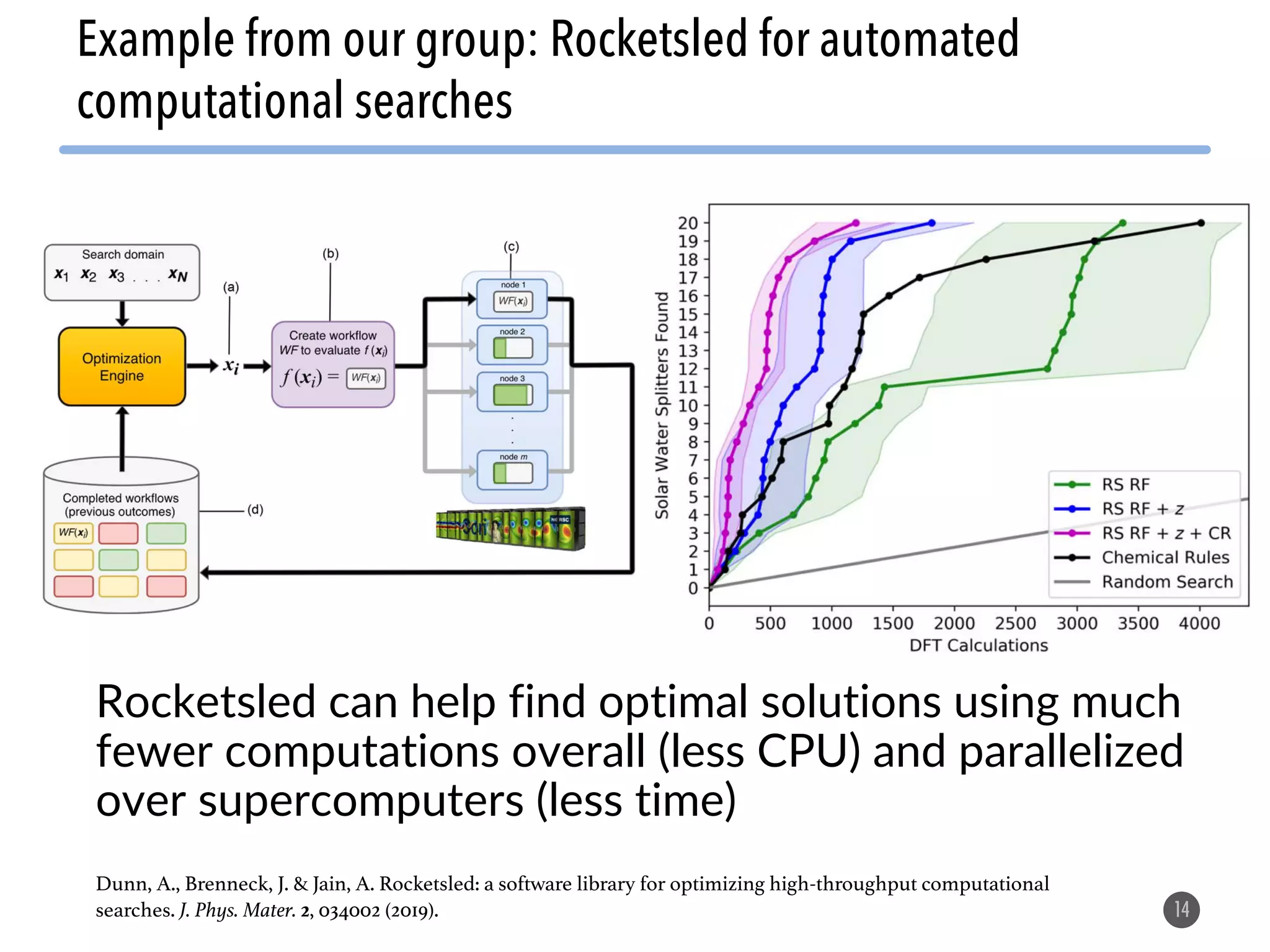

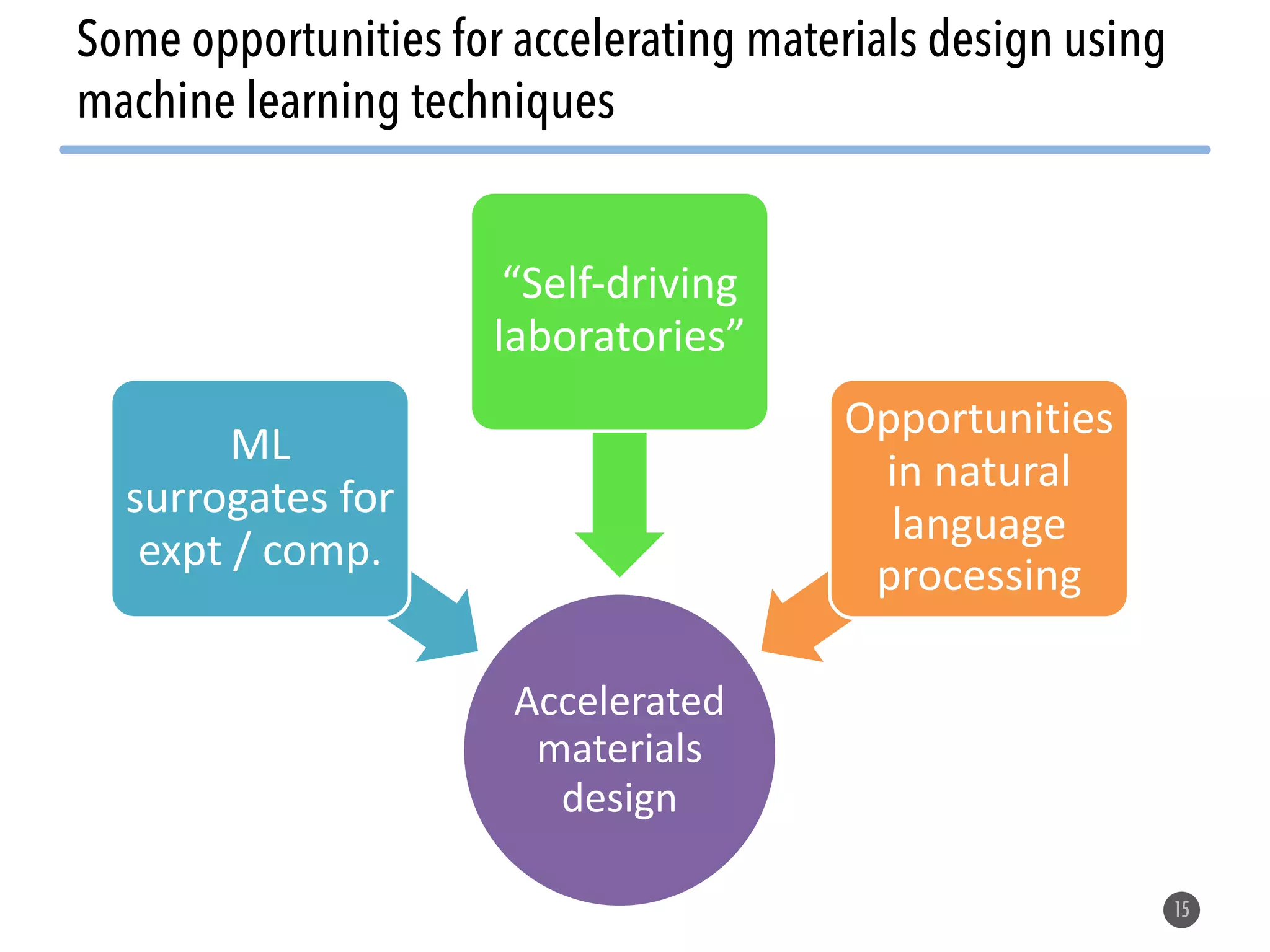

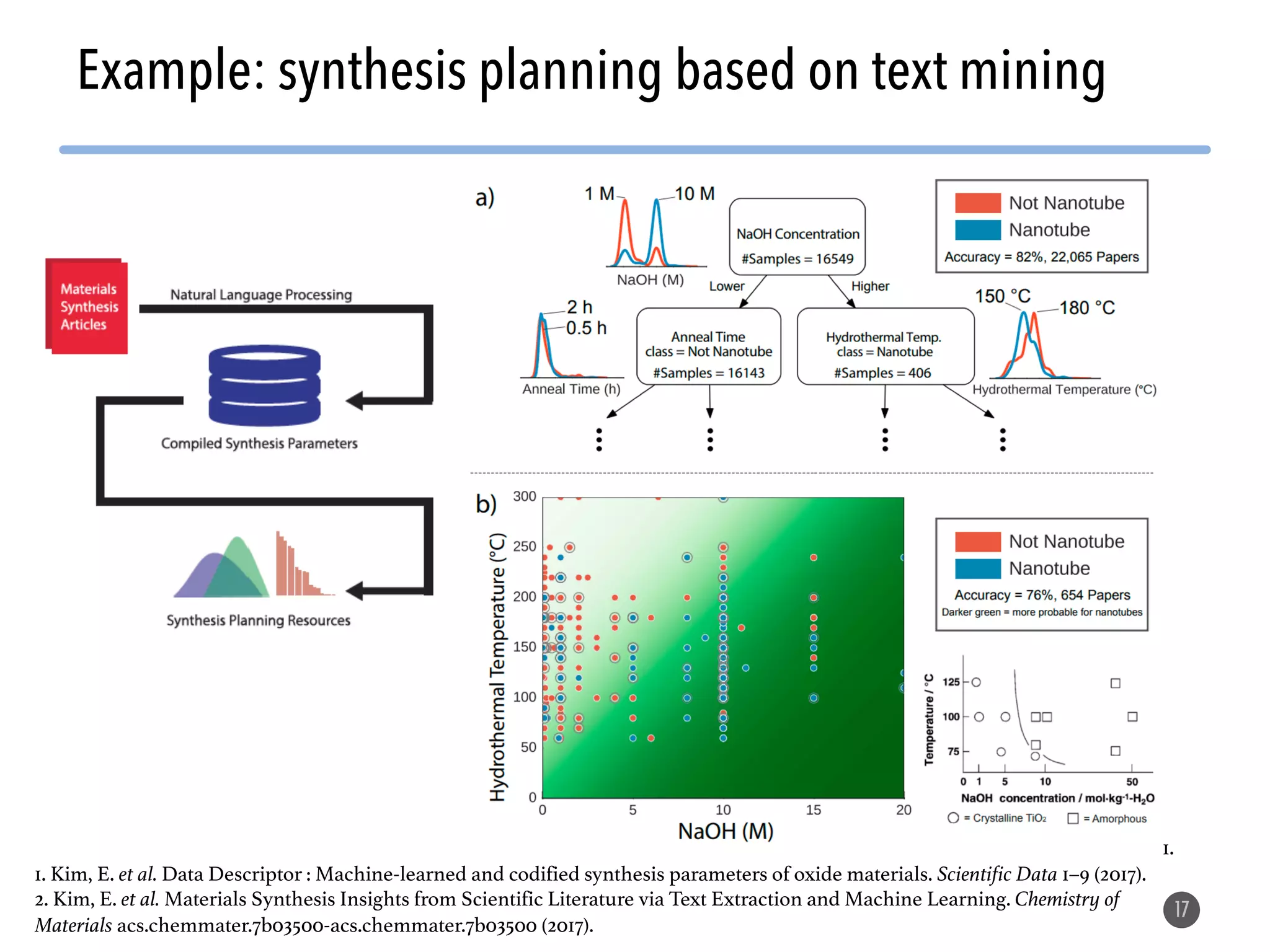

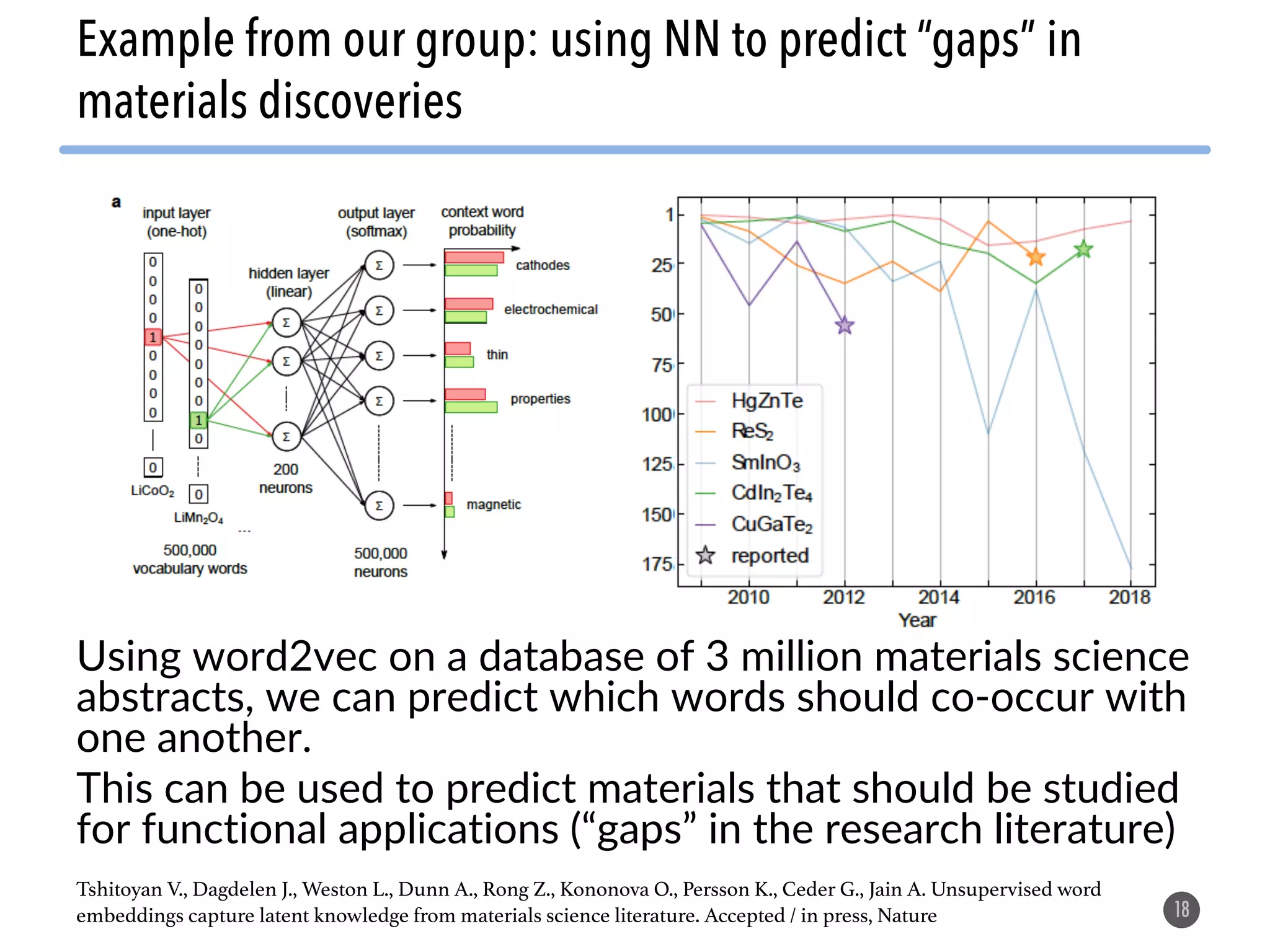

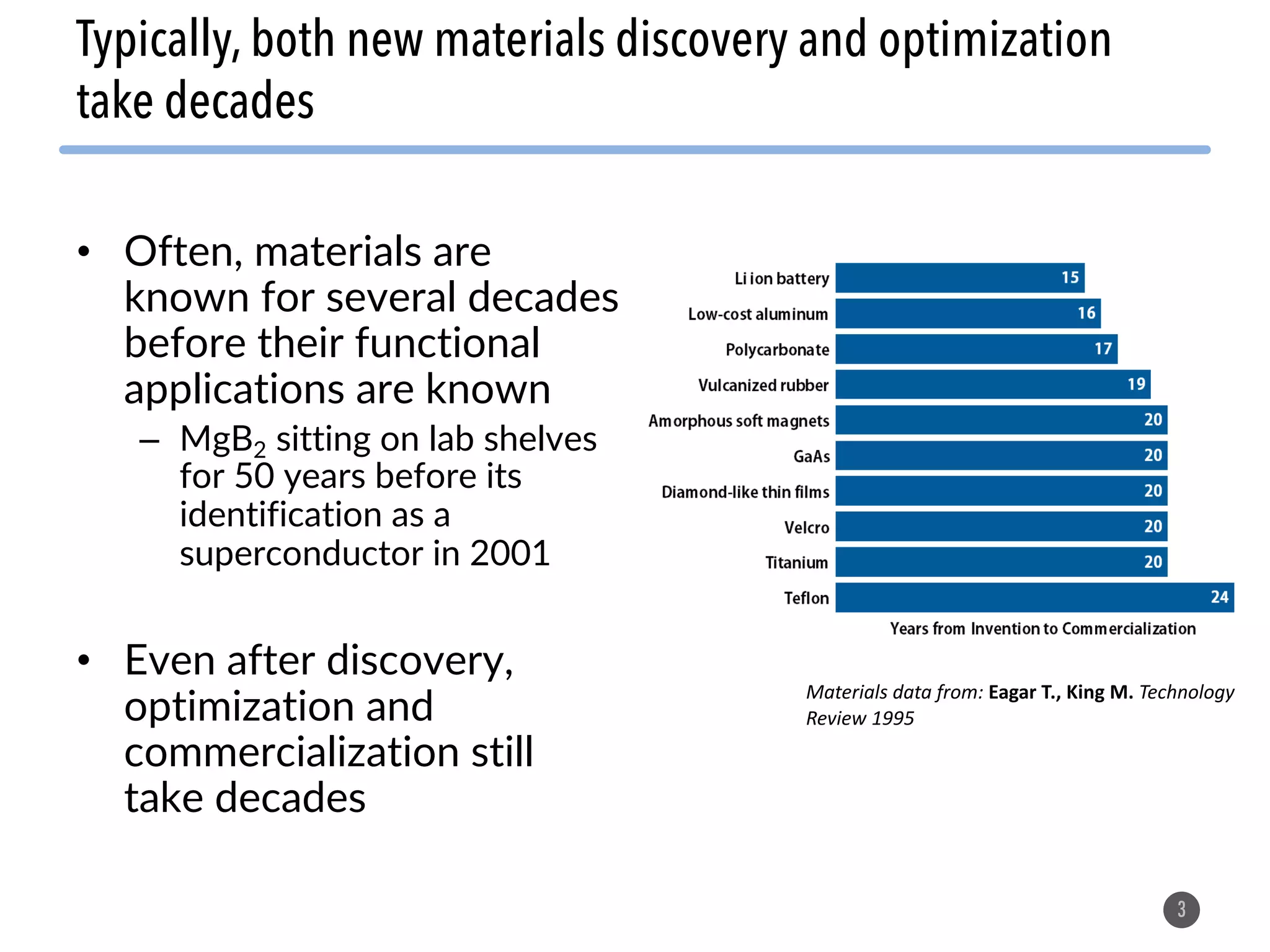

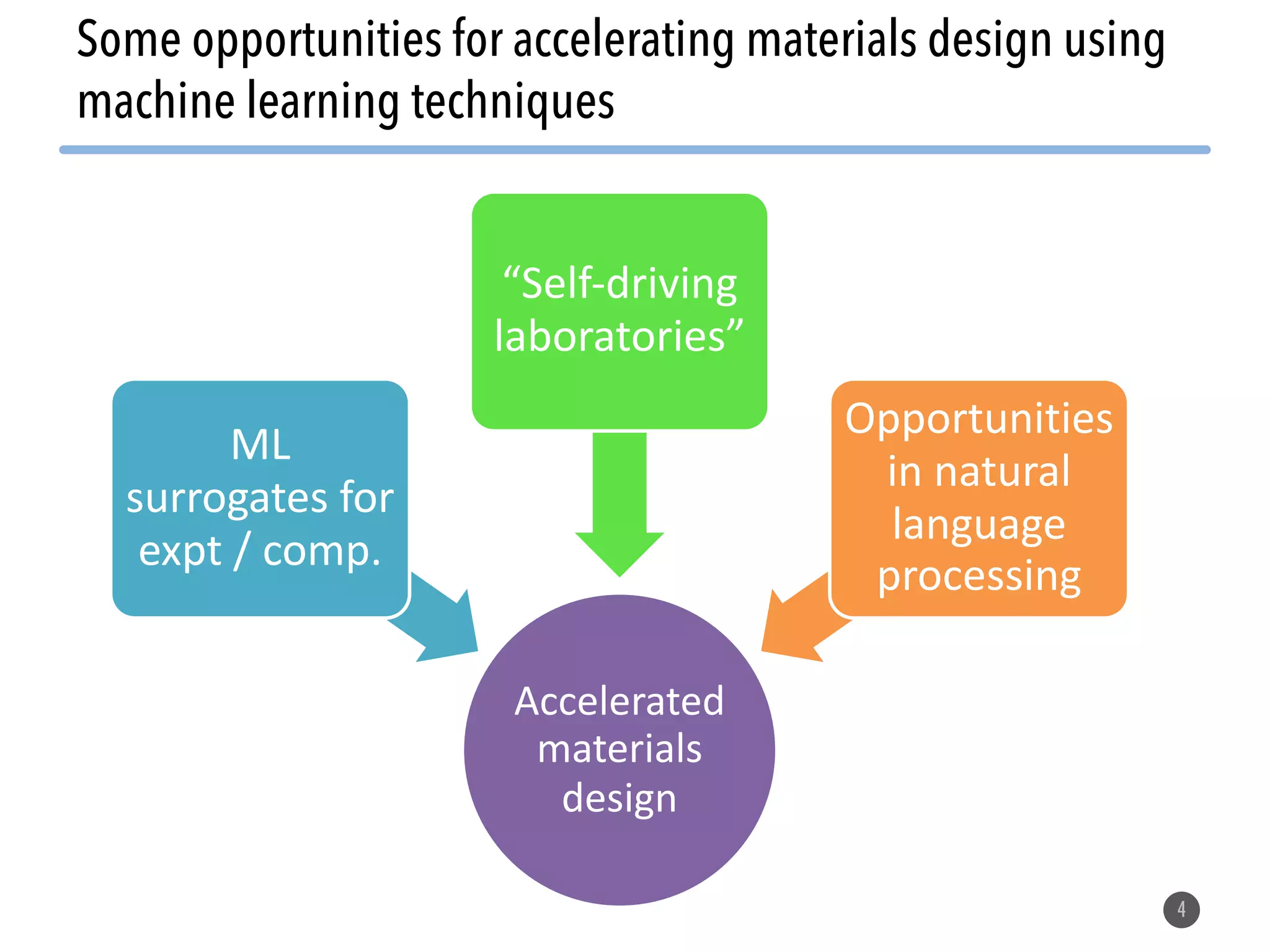

Machine learning techniques show promise for accelerating materials design by serving as surrogates for experiments and computations, enabling "self-driving laboratories", and extracting insights from natural language text. Key opportunities include using ML to screen large areas of chemical space before running computationally expensive DFT calculations or laboratory experiments. Challenges include limited materials data, data heterogeneity across problems, and ensuring ML models can accurately extrapolate beyond the training data distribution. Overcoming these challenges could substantially reduce the decades-long timelines currently needed for new materials discovery and optimization.

![• Computations can be faster and require less

researcher time

– Today, some materials design problems can be

modeled in the computer[1]

– But, CPU-time is still a major issue

6

ML surrogates for experiments and computation:

background

[1] Jain, A., Shin, Y. & Persson, K. A. Computational predictions of energy materials using density functional

theory. Nature Reviews Materials 1, 15004 (2016).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/20190513etacrdenergyprobe-190513173330/75/Machine-learning-for-materials-design-opportunities-challenges-and-methods-6-2048.jpg)