The document discusses three models of strategic communication: linear, adaptive, and interpretive. The linear model views strategy as long-term planning by top managers to achieve goals through rational decision making. The adaptive model focuses on continuously adjusting the organization to its dynamic environment through co-alignment. The interpretive model views strategy as managing meanings and symbols to legitimize the organization through shared understandings. It then covers characteristics like public communication, the communication source, and a transactional approach. Finally, it discusses the traditional perspective on internal communication topics like orientation, morale, and change, and external communication topics like public relations, issues management, and advocacy.

![Models of Strategy

• Linear

• Adaptive

• Interpretive [Chafee, 1985]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter-13-powerpoint-160218213444/85/LS-603-Chapter-13-Strategic-Communication-4-320.jpg)

![Organizational Change

and Development

• Strategic change depends on backing from those

who authorize change, accessibility in the sense

that managers understand what they are working

toward, specificity in terms of the detailed

planning, and cultural receptivity, i.e., those

affected by change are receptive enough to

facilitate it. [Miller, 1997]

• Successful change also depends on

propitiousness. Simply stated, accomplishing

major change also requires some luck.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter-13-powerpoint-160218213444/85/LS-603-Chapter-13-Strategic-Communication-23-320.jpg)

![Public Relations and

Image Building

• Image building is a process of creating the identity

an organization wants its relevant publics to

perceive.

• Image building involves an organization's attempt

to cultivate a public impression that a set of

positively valued features defines the essential

character of the organization. [Goldhaber, 1993]

• Changing a corporate image requires developing

and publicizing specific organizational

characteristics and behaviors that are consistent

with the image being cultivated.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter-13-powerpoint-160218213444/85/LS-603-Chapter-13-Strategic-Communication-27-320.jpg)

![Public Relations and

Image Building

• The art of image building is associated with the field

of public relations.

• Public relations has been defined as the

management function which evaluates public

attitudes, identifies the policies and procedures of an

individual or an organization with the public interest,

and executes a program of action to earn public

understanding and acceptance.

• Farsighted, contemporary public relations practice is

concerned with developing public appreciation of

good organizational performance [Cutlip & Center,

1964]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter-13-powerpoint-160218213444/85/LS-603-Chapter-13-Strategic-Communication-28-320.jpg)

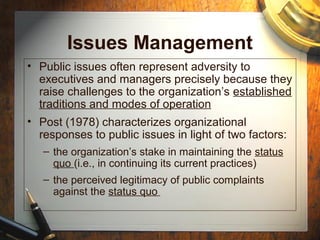

![Issues Management

• The organized activity of identifying emerging

trends, concerns, or issues likely to affect an

organization in the next few years and developing a

wider and more positive range of organizational

responses [Coates, Coates, Jarratt, and Heinz, 1986]

• Issues management in business emerged largely as

a response to the activism of public interest and

special interest groups and as a means of

identifying, understanding, tracking, and acting on

issues before they are subjected to public policy

deliberations and decision making [Jones & Chase,

1979]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter-13-powerpoint-160218213444/85/LS-603-Chapter-13-Strategic-Communication-29-320.jpg)

![Image Management and

Issues Advocacy

• Issues advocacy addresses itself to specific

controversial issues, presenting facts and arguments

that project the sponsor’s viewpoint to try to influence

political decisions by molding public opinion [Sethi,

1982]

• Pfizer advertised its Access program to help uninsured

persons obtain free prescription drugs when politicians

were debating addition of drug coverage to Medicare,

an action opposed by Pfizer.

• The message was an image ad in appearance, but it

functioned as an advocacy ad by implying that the

Medicare drug program was unnecessary.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter-13-powerpoint-160218213444/85/LS-603-Chapter-13-Strategic-Communication-36-320.jpg)

![Risk Communication

• Risk communication is the process of

communicating responsibly and effectively about

the risk factors associated with industrial

technologies, natural hazards, and human

activities.

• Risk communication is not about managing risks,

per se; it is about managing the divide between

the expert and the non-expert to achieve an

informed understanding of risks and benefits

[Leiss, 2004]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter-13-powerpoint-160218213444/85/LS-603-Chapter-13-Strategic-Communication-37-320.jpg)

![Risk Communication

• The basic responsibility of risk communication

practitioners is promotion of reasoned dialogue

among stakeholders on the nature of the relevant

risk factors and on acceptable risk management

strategies.

• In order to fulfill this purpose, practitioners must

understand how risks are perceived by relevant

publics, be able to present expert risk assessments

in ways that non-experts can understand, and help

interested parties reach a shared understanding of

risk [Leiss, 2004]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter-13-powerpoint-160218213444/85/LS-603-Chapter-13-Strategic-Communication-38-320.jpg)

![Crisis Communication

• Crisis: a major, unpredictable event that has

potentially negative results and may

significantly damage the organization [Barton,

1993]

• The purpose of crisis communication is to

respond appropriately in such situations to

minimize damage and maintain public

confidence](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter-13-powerpoint-160218213444/85/LS-603-Chapter-13-Strategic-Communication-39-320.jpg)

![Crisis and Stakeholder

Relationships

• Crisis communication in situations that affect the

organization’s relationships with stakeholders,

especially those that draw mass media attention,

requires management of those relationships

• If you begin with the value of an organization and

subtract from it the organization's material

assets, what you have left is the value that

perception creates

• You can lose that value in a nano-second in a

crisis [Englehart, 1995]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter-13-powerpoint-160218213444/85/LS-603-Chapter-13-Strategic-Communication-41-320.jpg)

![Strategy and Hegemony

• Increased economic and political tension between

the European Union and United States in recent

years has pushed the TABD into a dual rhetorical

challenge

• Promoting its success to business and government

participants to further its agenda while

encountering a small but growing activist

community protesting TABD's influence as an

example of corporate hegemony [Zoller, 2004]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter-13-powerpoint-160218213444/85/LS-603-Chapter-13-Strategic-Communication-54-320.jpg)

![Strategy and Hegemony

• TABD links dialogue with the public good and denies any

aims to weaken regulations on business, yet deregulatory

goals are apparent in its public communication.

• TABD represents dialogue as civil participation and its

own role as advisory and nongovernmental, but its goal is

incorporation of its expert group recommendations into

government policy.

• The effect of TABD’s strategy actually is to exclude

multiple viewpoints from dialogue on trade and business

policies: “Rather than contributing to increased public

debate, the process forwards only business interests and

only one version of those interests” [Zoller, 2004]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter-13-powerpoint-160218213444/85/LS-603-Chapter-13-Strategic-Communication-55-320.jpg)