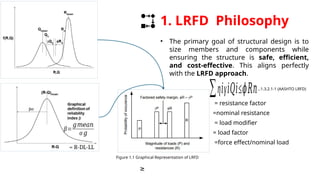

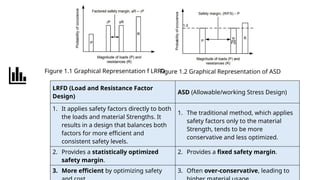

This is a genuine effort to understand load combinations as per AASHTO codes, though not all load cases are covered.

An additional note: The content is for study purposes only; I do not claim ownership or authorship, as it is compiled from publicly available sources.